Clicking Through Ages

Cyan and Myst

Thinking back on gaming as a child, there were obviously titles that made more of an impact than did others. Particularly for me (and obvious to my readers), those games were the Civilization series and the SimCity series. These were not, however, the first video games I played nor were they the only games I played. The Ohio river valley had a lot of rainy days that weren’t conducive to riding my bicycle, and that meant screen time.

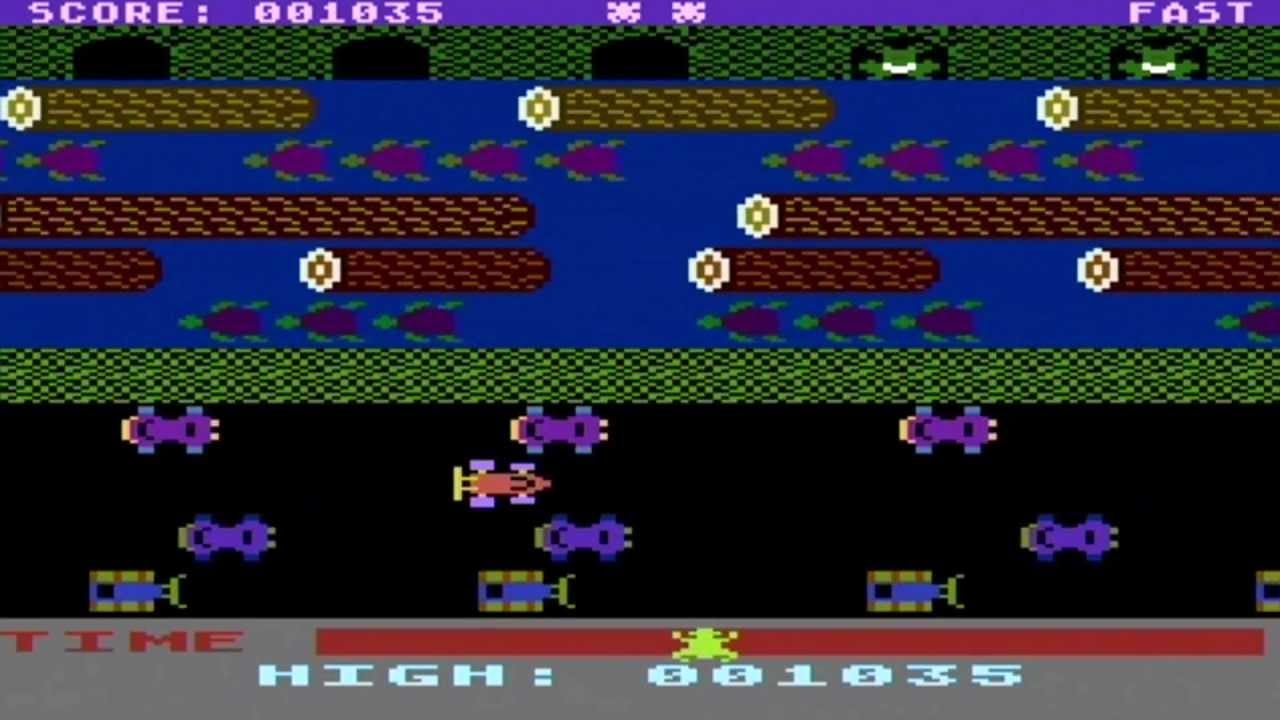

Games progressed quickly in their graphical fidelity when I was young. They started like this:

Then they became more like this:

Then they moved on to things like this:

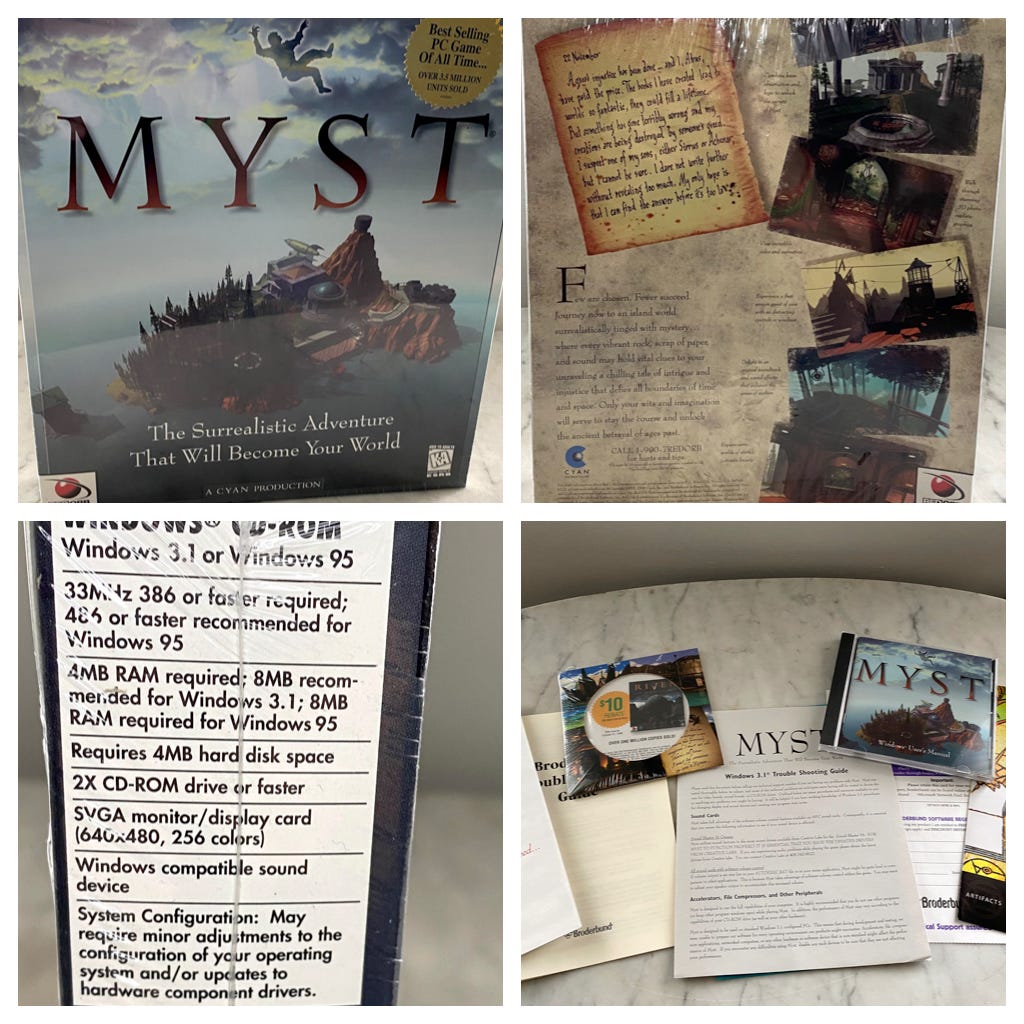

These were small and iterative improvements, and to me at the time, they didn’t matter all that much. Then, something changed. A game came out that looked like this:

This change was so dramatic that it was noticeable without question. This wasn’t a small iterative improvement. I didn’t understand the difference of pre-rendered graphics, and I didn’t understand the importance of Windows or CD-ROM to this kind of game, but I did understand that this was significantly more immersive.

When Rand Miller was in junior high, he was introduced to video games. A friend of his who was attending the University of New Mexico took him to school’s computer center. There, his friend showed him the game “Lunar Lander.” This was a purely text mode affair in which the player attempted to land on the surface of the moon by controlling the fuel burn of the lander. The readouts of height, fuel, attitude, and so on would then adjust on the screen. For Rand, this was a big moment. His friend said that not only were there other games but also that he could make his own new games. Rand was hooked and the trajectory of his life changed. Rand’s brother Robyn, on the other hand, was a writer, an artist, and a musician. If ever there were a suited pair for the making of video games, it is certainly that of artist and programmer.

Cyan was started by brothers Rand and Robyn Miller in 1987, and while Myst was Cyan’s first major commercial success, it was neither the company’s first game, nor their first CD-ROM title. Rand had the idea to make an interactive book, and this spawned their first title, The Manhole. Like their later early titles, this was a point-and-click adventure aimed at children. Robyn drew the first page which showed a manhole cover and a fire hydrant, and the two of them looked at it. They realized that they didn’t really want to turn the page, but instead they were interested in what was under that manhole cover. Rand took Robyn’s drawings, and he began to work on movement and exploration with HyperCard. So, the next step was to have the manhole cover slide over after having been clicked and a large vine growing up out of the manhole. The two quickly realized that an interactive book wasn’t the goal. The creation of worlds was the goal. They followed this with Cosmic Osmo. Here the player had a spaceship and could explore 7 different planets.

Sunsoft had been funding the conversion of The Manhole for the Japanese market, and they now wanted a title for adults. They offered $250k in 1991 (around $556k in 2023) for this effort. Rand and Robyn rented a hotel room for the meeting and served coffee. They were nervous but the primary question that was asked was whether or not their title would be better than The 7th Guest by Trilobyte. Naturally, they said: “Oh yeah, it’s going to be better.”

At the time, Robyn was enjoying Jules Verne’s work The Mysterious Island and this is where the name came from. The influence of islands from that story helped as memory was limited on computers of the time. Having several islands would aid in keeping the areas small. The other thing that this accomplished was helping to circumvent the limitations of early CD-ROM. A 1x CD-ROM drive can read data at 150 Kbyte/s in optimal conditions. Seek times can make that substantially slower. By having small islands in different “Ages,” Rand and Robyn could organize data on the CD-ROM according to what a player was most likely to see next. They could also take advantage of the color limitations and screen resolution limitations that most people would have; so all images were 8 bit (256 color), and the screen resolution was limited to 640x480. After compression, the images were around 50k. This was vital. The game also has sound, and room had to be left both on disk and in bandwidth to get sound in-time with on-screen visuals. Any major seeking or long reads would slow the progression and make the game less engaging.

Cyan was obviously a small indie game studio, and at this time in history games were only released on physical media. This meant inventory. All of the details of publishing to physical media would require a large amount of staff. As a result, most smaller game studios relied on publishers. For Cyan this was Brøderbund. Brøderbund wanted to test the game with a focus group. The first group absolutely hated Myst, and the brothers were left wondering whether or not they had wasted their time, their money, and their work. They needn’t have feared. The second group loved it.

Myst was initially released on the 24th of September in 1993 for the Macintosh. Other notable games of 1993 were Mortal Kombat, Street Fighter II, Star Fox, Mario Kart, X-Wing, Doom, and Streets of Rage II. All of these focus on action of some kind, some level of violence, and allow for multiple players (well, most of them anyway). Myst has no real “action,” it is single player, and it’s a point-and-click adventure that lacks risk. Myst relies on mystery, beauty, and narrative to create its playability. As the sales of the game proved, Myst was quite successful in achieving playability. In its first year on the market more than 200,000 copies of the game were sold; this would continue to climb to six million until 2002. Until then, Myst was the best selling game in history. It was finally unseated by The Sims. A Windows 3.1 release followed in March of 1994, 3DO in March of 1995, SEGA Saturn in September of 1995, Atari Jaguar in December of 1995, and finally the Sony Playstation in September of 1996.

The story of Myst starts with the player opening a mysterious book, whereupon he/she is transported into a different world, finding himself/herself standing on the dock of a small deserted island. The player soon learns that he/she is following a trail first followed by a father and his two sons who had the ability to travel among worlds known as Ages. These Ages were written in linking books, and through these the authors of Ages could likewise alter worlds already written. The father has passed, and the two sons have been trapped in different Ages blaming one another for the death of their father. The player of Myst has the ability to access Ages after solving requisite puzzles, finding pages for the linking books, and then putting the pages together.

Myst isn’t too dissimilar from text adventures or from Sierra games before it. There’s a maze, a network of locations, and navigation is part of the challenge of the game. The puzzles where one thing done in one location will affect something in another is reminiscent of Infocom. The point-and-click nature of the game is very much like Sierra games. These were not intentional similarities as far as I know, but they’re definitely there. Unlike other adventure games, the player cannot die, cannot have an inventory, and there are no “stats”, no lives, no power-ups. The player simply explores a world.

Myst changed the way I thought about gaming in general. Prior to Myst, I hadn’t really thought of games as art. Games were something distinct, something other. Myst made me realize just how much a game is a work of art. It is an expression of emotion, imagination, and so much more. Every game had always been this, I’d just not realized it. I’d always thought of games merely as toys, and Myst was the title that changed my perception.

When I first played Myst, it was on a 75 MHz Pentium (P54C on socket5), with 16 MB of RAM. If I recall correctly, this machine had a SoundBlaster 16 in it. I remember for certain that it was later upgraded with a Matrox Mystique video card in 1996, and that it was upgraded from Windows 3.1 to Windows 95 around the same time. Those memories stand out primarily because my father walked me through the process of these upgrades, explaining each part’s function, what drivers are, what jumpers are, and so many other details. So, for me, Myst is intimately tied not just to how I view gaming, but also to good memories surrounding the machine on which it ran.

For Cyan, Myst propelled the company to certain level of fame, and it built a loyal fandom for the company. They continue creating worlds today.