Intel Inside

Strategic Revolution

The last of the 20th century was off to a great start with demand for both the i386 and i486 exceeding Intel’s ability to supply in 1990. While CPUs were Intel’s biggest product, the company was also developing and delivering peripheral chips, microcontrollers, digital video controllers, flash memory, and EPROMs. The company also began working with the Concurrent Supercomputer Consortium on a design that utilized 570 Intel processors (i860 and i386) to provide 32 billion FLOPS of computer power. This was a large improvement over the prior iPSC/860 built of 128 i860 CPUs providing 7.6 billion FLOPS. While not often discussed, Intel was the largest supercomputer provider at the time by number of machines shipped.

In October, Intel released the i386SL. This part was intended for laptops and other mobile computing devices powered by battery, and it featured power-management features like SMM and sleep states. It could make use of external cache ranging from 16K to 64K and was first available at a speed of 20MHz. Physically, the chip was lighter and smaller than its desktop brethren while also having a great deal more transistors on chip (855,000 in the SL vs 275,000 in the SX). A 25MHz part shipped not too long after, and a 16MHz part not long after that. These all became available in low voltage variants as well.

On the 5th of November in 1990, Intel announced the i750 video processor priced at $100 for volume purchases. The goal with this product was to offer video capture and compression at a lower price point than had previously been available. Intel targeted a retail board cost of $699 with the ability to capture video and compress it in real time as Indeo files (ivf usually in an avi container). At this time, this usually would have been a two-step process. One would capture the video in a raw format and then compress it after. Hardware to accomplish this was also typically priced out of the reach of any individual consumer. This was a two chip design comprised of the 82750PB pixel processor and the 82750DB display processor. The PB was clocked at 25MHz, executed instructions in a single cycle, and utilized wide instruction words. It had 512 by 48bit instruction RAM, 512 by 16bit data RAM, two internal 16bit buses, it’s own ALU, variable length sequence decoder, pixel interpolator, 32bit data bus (50MB/s max), 16 general purpose registers, and 4GB linear address space. It was manufactured on a CHMOS IV process and packaged in a 132-pin PQFP. In practice, this chip could handle 30 images/second. The DB operated at 28MHz with modes for 8bit, 16bit, and 32bit pixels of selectable widths. It could support VGA, NTSC, PAL, and SECAM with a triple DAC for analog RGB/YUV output. It could mix graphics and video pixel by pixel, and it had three independently addressable color paletts. Together, these two chips achieved Intel’s aims and an owner of an i750 board could capture video, add graphics to the video if wanted, and compress it as an Indeo file in real-time at 30fps.

Intel closed 1990 with $650,261,000 in income on revenues of $3,921,274,000. For the first time, Intel’s largest growth wasn’t in North America or Europe though those two regions remained the largest for total sales. In 1990, Intel captured 72% of the Asia-Pacific market for CPUs. They had offices all over the region, but those that were most responsible for the company’s success were, according to Intel, in Hong Kong, Singapore, South Koprea, Taiwan, and the PRC.

In 1991, the biggest product from Intel was the EtherExpress LAN adapter card line. Drivers were made available for PC-DOS/MS-DOS, NetWare, OS/2, Windows 3.x with drivers later available for NT and 95. Later revisions of these cards dropped the BNC connector, transitioned to 32bit PCI and MCA, and brought higher bandwidths. Of course, the network controller on the card was also used in 23 different and distinct SKUs targetting various market segments. These LAN adapters were made available in September and Intel had immediate success with them.

Dennis Carter was born and raised in Kentucky. He earned his BS in electrical engineering from the Hulman Institute of Technology in Terre Haute, Indiana in 1973 and his master’s from Purdue in 1974. He worked at Rockwell for a bit after graduation, and while he enjoyed engineering work, he liked customers more. He found great enjoyment in explaining the technologies and their benefits. He enrolled at Harvard Business School in 1979. With his MBA, he went to Silicon Valley and found employment at Intel.

His first tasks at Intel were selling the i386 and i486. Honestly, most people (both OEMs and end-users) were happy with their 80286 machines or V20s, and the market for advanced 32bit CPUs was one of power users. The company spent most of its marketing and sales budget going after design engineers at PC companies. Carter’s insight was that these really weren’t the people making the buying decisions anymore, marketers were. If it could be made easier for a marketer to generate interest in a new product, the company would would buy the part from Intel and build the new product.

Grove wrote to Moore:

Dennis, in his new job, is moving with great speed toward running a test ad. The latest is that he is going to run the test in Denver to help move the market to 32 bits [from the 16-bit 286 to the 32-bit 386]. It’s a controlled experiment all set up very thoughtfully and professionally, but done in a hurry, because if it works and we do it on a bigger scale, it has to happen in the next few months in order to have an impact on the PC selling season this year. The ad is imaginative-strikes me even as brilliant-but bold and agressive. It has been blessed by all the top guns in marketing, including Gelbach, who was consulted as a disinterested bystander.

I predict that you’ll hate it.

Intel saw itself as an ingredient maker. While the company had developed and released complete computer systems over the years, these were never intended for the retail market. As such, end-user marketing wasn’t welcome at Intel, and was, in fact, met with hostility. This presented an issue for Carter when marketing their products. Yet, the fact that i386 adoptions were slow provided him a bit of freedom. He took the opprobrium on the chin, formed a team of five, and flew to Denver. With the i486 launch imminent, he went and bought newspaper ad space and billboards. Carter’s team ran polls before and after the ad campaign in Denver. It worked. The campaign made it to nationwide release at a cost of $5 million. It worked again. Sales went up.

The ad he ran would have made his coworkers’ blood run cold. It was “286” in black ink, a red X under it, with “386SX” on the next page. Defacing the company’s own products was quite unprecendented, but Carter figured that he needed to get people’s attention. Doing so then meant making the advertisement truly standout among other advertisements. This also subtley showed that Intel’s biggest competitor was itself.

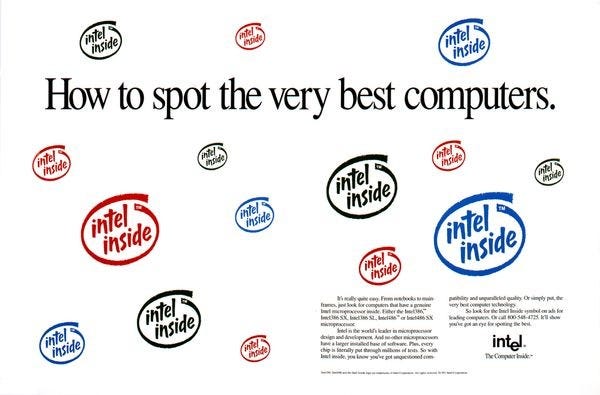

Carter’s goal wasn’t merely to sell the i386-class of CPU. In 1990, AMD ended the Intel monopoly on the 386. Thankfully, NutraSweet had pioneered ingredient branding starting in 1981, and ten years later, Carter was ready to adapt their strategy. What he saw was a mass-market campaign with cooperative advertising with OEMs. Intel would pay part of the cost of an advertisement for a PC manufacturer’s product if that advertisement included Intel and the computer had a case badge attesting to its use of an Intel processor. An ad agency had come up with “Intel, the computer inside,” but this became “Intel Inside” as Carter worked at it.

This too was a gamble. Would system makers want to dilute their brand by mixing it with Intel’s? Would this hurt their sales of AMD-based machines? One move to ameliorate these concerns was that Intel wasn’t written in the style of the corporate ID with the lowered ‘e’ but rather in what appeared to be handwriting. When Carter presented the program to the executive staff, everyone thought it was a terrible idea. Yet, here again, Andy Grove approved referring to the idea as brilliant. By the end of 1991, 342 OEMs were involved in the Intel Inside program. The ads were everywhere, and sales went up dramatically. The campaign made its way onto television and the four-note Intel jingle became well known.

Not all news for the year was good. AMD and Intel continued their legal battles with new lawsuits being filed by each while others were dismissed or settled. One of these was a loss on the copyright of the 386 name. William Ingram ruled on the 1st of March that it was too generic. Still, it was a great year for Intel with income of $818,629,000 on revenues of $4,778,616,000

With Intel advertising directly to end-users, the company introduced their first major retail boxed processors on the 26th of May in 1992: Intel OverDrive. The distinction of “major” is carrying quite a bit of weight here as the company had released products like the InBoard 386 in the past, but these were never strategic product pushes from Intel. Intel OverDrive CPUs were intended to be used explicitly as upgrades to existing i486 systems. These brought with them voltage regulators, write-back cache, heatsinks, and other improvements that brought original i486s more in-line with the 486DX2 launched the same year. The i486DX2 was, mostly, a clock doubled 486DX running two internal logic clock cycles per bus cycle, but it also added an 8K on-chip cache. These were built on an 800nm process, and they offered around a 70% speed improvement over their ancestors.

On the 21st of June in 1992, Intel announced the Peripheral Component Interconnect standard. They’d been working closely with IBM, Compaq, NCR, and DEC who, together with Intel, formed the PCI Steering Committee. This was followed by the 420TX chipset for the PCI bus in November. Another standard introduced was the Indeo video technology for the i750 mentioned earlier. This was done in cooperation with Microsoft, Apple, and IBM.

Intel became the world’s largest semiconductor in 1992 and paid its first cache dividend on Intel Common Stock in December. Revenues for the year were $5,843,984,000 with income of $1,066,549,000.

Given that the 386 and 486 names were too generic for copyright, Intel held a company-wide contest for the name of what would otherwise have been the 586. Many different people suggested using the Greek penta (five) as part of the name. The suffix ium commonly used to form nouns for words of Latin or Greek origin was then added forming Pentium. The company awarded 18 employees the contest prize of $200 for the suggestion. The Pentium was launched on the 22nd of March in 1993. It had been designed starting in 1989 by the same team in Santa Clara who’d been responsible for the i386 and i486, but the team grew to include some 200 engineers. The Pentium slightly extended the 486 instruction set and removed test registers TR0-TR7. Otherwise, it was superscalar and featured dynamic branch prediction, a piplined FPU, faster instruction execution, separate 8K code and data caches, a 64bit data bus, bus cycle pipelining, address parity, internal parity checking, functional redundancy checking, execution tracing, performance monitoring, system management mode, and virtual mode extensions. It reduced address calculation to a single cycle, sped up 8086 emulation, reduced the number of cycles required for multiplications, and could achieve 100 million instructions per second at 66MHz. The first Pentium was sold in 60MHz and 66MHz versions built of 3.1 million transistors on an 800nm BiCHMOS process. It was packaged in a 273-pin PGA for Socket 4, ran on 5 volts, and consumed around 13 to 17 watts.

With the Pentium came the need for a new chipset, and one was provided simultaneously with the launch. This was the 430LX supporting an FSB speed of 66MHz, operating at 5V, and utilizing FPM memory of up to 192MB. The 430LX was built of the 82434LX with two 82433LX chips.

Intel closed 1993 with income of $2.295 billion on revenues of $8.782 billion. They’d spent around $970 million in 1993 on R&D, and even more on plants and equipment. Much of this was on 600nm and 400nm fab builds. The Intel Inside program had nearly 1400 partners, and more than 133,000 PC advertisements had used the Intel Inside logo. At 25 years old, Intel was the undisputed king of the semiconductor world.

I have readers from many of the companies whose history I cover, and many of you were present for time periods I cover. A few of you are mentioned by name in my articles. All corrections to the record are welcome; feel free to leave a comment.