The ENIAC

Changing the Word Computer with the Electronic Brain

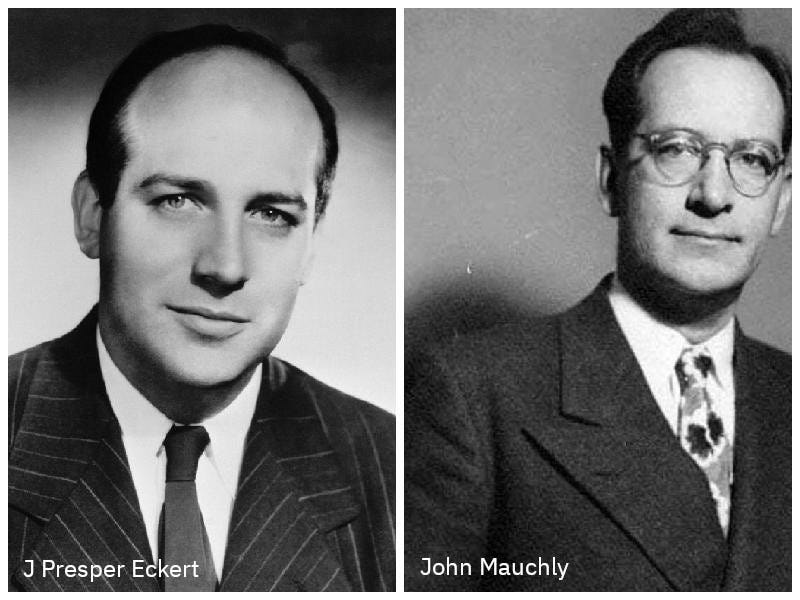

John Adam Presper Eckert Junior was born on the 9th of April in 1919 in Philadelphia to a wealthy real estate developer, John Eckert. He was raised in a home in Philadelphia’s Germantown, and during his youth attended the William Penn Charter school. From a very young age, Eckert was interested in electronics. At five years old, he could often be found sketching radios and speakers. At twelve years of age, he won the Philadelphia science fair by building a remote-controlled sailboat. In his high school years, he joined the Engineer’s club, and spent most of his afternoons at the school’s electronics laboratory. During this time, he replaced the battery-powered intercom system in one of his father’s apartment buildings with one connected to the electrical mains. He also made some money installing sound systems for schools and nightclubs. For his higher education, Eckert first enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School with the initial aim to study business and one day take over his father’s enterprise. This didn’t suit him. He transferred to the University of Pennsylvania’s Moore School of Electrical Engineering in 1937. He participated in research, improved the school’s differential analyzer, learned German and French, and began teaching a summer course in electronics as part of the War Department’s efforts to train and mobilize the research and engineering fields.

John William Mauchly was born on the 30th of August in 1907 in Cincinnati. His family moved to Chevy Chase, Maryland while Mauchly was still young due to his father having been hired by the Carnegie Institution of Washington as the head of the Terrestrial Electricity section. Much like Eckert, his interest in electronics began at a very early age and he excelled in school. Unlike Eckert, his early interests didn’t involve invention, but rather repair. He was frequently found doing electrical work for neighbors. Also unlike Eckert, his interests were more varied. Mauchly was an active member of the McKinley Technical High School’s debate team, and the editor of the school’s newspaper. Mauchly’s academic excellence earned him a scholarship at Johns Hopkins University where he was initially studying Electrical Engineering as a stipulation of his scholarship. While engaged in his undergraduate studies, he provided tutoring services to other students, and he occasionally gave lectures on physics. One particularly lengthily-titled lecture was about Einstein’s Theory of Relativity: “A Popular Lecture on the Patent Clerk Who Became a Pioneer in Mathematics and the Theory Which Gave Physicist and Philosopher Something to Talk About.” The EE track, however, wasn’t entirely to his liking. In a letter to his father, Mauchly lamented that the course was far more theoretical than it was practical. By his second year, he began to find the work less-than-challenging, and he sought a cure. Mauchly eventually found his answer in a provision whereby an outstanding student may enroll directly in a Ph.D. program before completing his/her undergraduate program provided that the student enter the graduate physics program at the university. This was the path that Mauchly chose in 1927.

For Mauchly, this wasn’t a happy time. One would assume that more challenging work would have been very pleasing to him, but it is more likely that his intensity was derived from emotional avoidance. Mauchly’s father, Sebastian, had contracted a chronic and fatal illness in the course of his job-related research work. Sebastian passed away around Christmas in 1928, and Mauchly didn’t leave the school. Indeed, he used the envelope for the letter that brought this news to him as a notepad. Mauchly submitted his dissertation to the faculty of Johns Hopkins University in 1932: “The Third Positive Group of Carbon Monoxide Bands.”

Mauchly had some rather bad luck in the timing of his graduation. The Great Depression was well underway and hampered his job prospects considerably. He eventually accepted an offer for a professorship at Ursinus College in Collegeville, Pennsylvania not far from Philadelphia. He taught physics, but he had precious little access to state-of-the-art equipment to engage in any research that would have been trendy at the time. One thing he could easily gather was meteorological data from all over the world. A consequence of this was that he developed a serious preoccupation with attempting to make calculations more quickly. The calculations became more interesting to Mauchly than the meteorological data itself as he had little success in getting any colleagues to share an interest in meteorology. Meteorologists themselves were skeptical of statistical approaches which only further pushed Mauchly toward calculation. Mauchly’s resources were very limited, but he began designing, building, and testing electronic calculation equipment. His first device was a flip-flop built using neon gas tubes as he couldn’t afford vacuum tubes.

On the 14th of May in 1941, Mauchly received a letter from Knox McIlwain, Director of Engineering Defense Training at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering, inquiring as to whether or not Mauchly knew of any prospective students for a new program:

Dear Sir,

We are planning to run a special Summer School at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering this year in connection with the Defense Program. Surveys have shown that there is a serious, if not critical, lack of trained engineers available to industry to effectuate the industrial mobilization required in the time available. Some surveys put this lack as high as 40,000 men. In any case, there is a terrific demand for engineers and the pressure on the present group is very serious. All of our men this June have had a plurality of offers.

On the other hand, we hear reports that the mathematics and physics graduates are not finding as great a demand for their services. One object of this letter is to verify this rumor. Our thought was that by taking trained mathematicians and physicists and giving them a ten weeks’ dose of concentrated electrical engineering, we could put them in position to enter engineering departments in factories as assistants. Their broad prospective and thorough training should enable them to win a full time engineering job within a very short time.

Any student who has a Bachelor’s degree, or a higher degree, in Mathematics or Physics will be admitted to this course. The course will also be open to a senior student in Mathematics or Physics upon recommendation of the Head of his Department. It will be expected that the latter group of students will return to their respective departments in the fall and complete their work for the degree in that Department.

The course would consist of four classes each day: Electric Circuit Theory, Electrical Measurements, Electronics, and an option between Electrical Machinery and Electrical Communication. Since these men would not be as familiar with machinery as the usual engineering graduate, it would be planned to have them in laboratory every afternoon. The courses would be taught in the main by our regular faculty and would in general cover the electrical subjects given in our regular four year course insofar as would be possible in the time available.

Thing is, while Mauchly almost certainly knew of great candidates for this course, he wanted to take the course himself, and so he signed up. Eckert was one of his instructors in the course and reported that Mauchly already knew most of the material. From Eckert’s words on the matter, he suspected that Mauchly was more interested in access to the labs. The two gentlemen formed a good working relationship over that summer.

Multiple efforts of the War Department were underway at the Moore School, and the demand for additional faculty was quite high. Upon his completion of the course, Mauchly was offered a position as an adjunct instructor. His duties were two-fold: research, teaching. He took over the instruction of some of the basic electrical engineering courses that were now open for new teachers due to war research demands having taken the previous teachers’ time. He was also assigned to a US Army Signal Corps project to calculate antenna radiation patterns for use in radar. Mauchly needed staff and hired a group of computers (the human kind, and typically female at this time in the nation’s history) to assist him. Not content with a full plate of work, Mauchly was also studying cryptography.

In the summer of 1942, Mauchly wrote a memo that outlined the idea of using counters and electrical switches wired together to do some computing, or in other words, to make an electronic computer, The Use of High Speed Vacuum Tube Devices for Calculating. He began working closely with Eckert on this project, and he filled Eckert in on his previous work with neon gas tubes. While gas tubes were cheaper than vacuum tubes, they also used less power, had a longer life, and required simpler wiring. The primary problem these devices had was that they were quite slow. Most historical reports of this memo regard this as the outline of the first large-scale, digital, electronic, general-purpose computer. I couldn’t find a copy of it, but this assertion is disputed by Eckert who recounts that at this time Mauchly’s ideas were not fully formed.

Regardless of whether or not the initial memo was a true computer design or not, the recommendation in the memo immediately gained traction at the university. The school was tasked with compiling range tables for the Army which required accuracy to within about a tenth of a percent. The mechanical differential analyzer at the school frequently had a margin of error around one percent (or worse) with ten mechanical integrators (later upgraded to fourteen). The result then had to be looked at by a human and corrected manually by a human computer. Their analyzer was later upgraded by Eckert to become an electro-mechanical machine that even had a few hundred vacuum tubes to speed certain calculations. Despite all of the effort to improve the analyzer, something better was clearly needed.

In 1943, Eckert was a sort of university-wide, defense project consultant. The Dean assigned him that way as he’d already been involved in an unofficial capacity in most projects, coming up with solutions and ideas that were good enough so that most people were happy to have his help, and he was happy enough to provide it. The new computer became one of these projects in which he was involved fairly immediately.

Following the release of the memo, Eckert and Mauchly completed a true and formal design of the machine with some help from Frazier Welsh, Irven Travis, and Phil Cook, and they submitted the official proposal for it in April of 1943. The contract was signed on the 12th of April in 1943. The resulting project was named Project PX and the Army provided $500000 (around $8.8 million in 2024) for the machine’s development with the contract officially being signed on the 5th of June in 1943. At the start of the project, Mauchly’s position was that only of a consultant. While he would discuss things with Eckert and others after hours, he didn’t get to work freely on the project he put in motion. The rest of the team included Robert F. Shaw, Jeffrey Chuan Chu, Thomas Kite Sharpless, Jack Davis, Jean Jennings, Marlyn Wescoff, Ruth Lichterman, Betty Snyder, Frences Bilas, and Kathleen Kay McNulty. Additionally, work on programming languages for the system was done by John von Neumann, John Mauchly, JP Eckert, Herman Goldstine, Alan Turing, Richard Clippinger, Kathleen Booth, and Haskell Curry. Goldstine’s wife, Adele, and John Mauchly’s wife, Mary Augusta also contributed in various ways. John Grist Brainerd was the principle investigator, Eckert was the principle engineer, and Herman Goldstine was officially in charge.

Early on, members of the team took a trip to Bell Labs, Eckert recounts:

We went and looked at the work that Bell Labs had done. They had a complex multiplier--sometime earlier--I think about '37 or '38 but I'm not sure of the dates. They had actually hooked it up to remote terminals in another city through the telephone lines. If you do network problems and telephone transmission problems, there's a lot of multipliers of complex numbers and this machine was specialized to do that task.

Bell wasn’t their only source of inspiration. The team also drew upon work being done at Harvard on the Mark I and from Atanasoff’s ABC.

To provide some color to how things worked on the team, from Eckert again:

Oh well, there was a guy by the name of Sharpless who, in one of the most critical times in the project, went on vacation without telling me. His boss said he was going to do it. He left a note in his mail box and said, "I'll be back in a week," or something and the big problem was that he was working on the central cycling unit. That first panel sent patterns of pulses around to all the other units and synchronized them together. We were really stuck. Without it we couldn't test anything else. So Mauchly and I personally (more or less) put down what else we were doing in the project and took a soldering iron and made that thing work ourselves. So, he [Mauchly] did do things like that but that was not the general mode of his operation or mine. My general mode of operation was to go around and find out every morning what people were doing and what their problems were and make suggestions on how they might solve them. If the problems were too great, we'd call a meeting and get everybody's ideas. And then we had the everyday things of making sure we had enough wire, and parts. An awful lot of time was spent with Goldstine and we'd look at books and find out if we can find some couple thousand tubes that the Army didn't need. We used 10 different types of tubes in that machine. I could have done it with 4 or 5 but I couldn't get enough of certain types so I would find a tube that I could get and then I would just find a circuit that it seemed to fit best and probably got some gain. But it probably took more time because I had to design more circuits.

Project PX resulted in ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer) which was the first programmable, electronic, general-purpose, digital computer. The ENIAC’s first production job was completed on the 10th of December in 1945. The machine was unveiled to the world through a press release on the 14th of February in 1946, and it was accepted by the Army Ordinance Corps in July of 1946 and subsequently transferred to the Aberdeen Proving Ground in 1947.

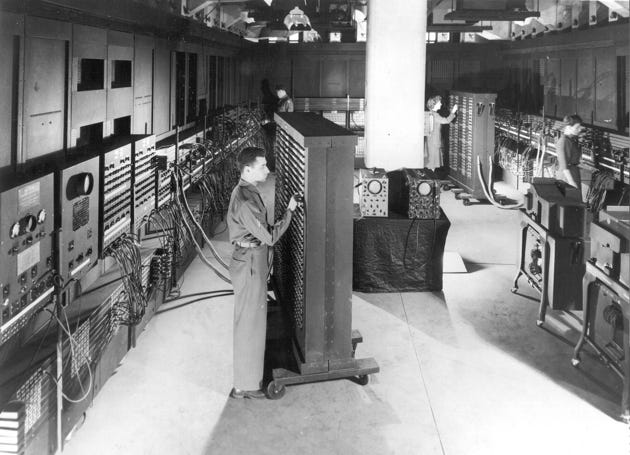

ENIAC was built of seventeen thousand four hundred sixty eight vacuum tubes, seven thousand two hundred crystal diodes, one thousand five hundred relays, seventy thousand resistors, ten thousand capacitors, and five million hand-soldered joints. It weighed twenty seven tons, was eight feet tall, three feet deep, one hundred feet long, and generated one hundred fifty kilowatts of heat while consuming around one hundred sixty kilowatts of electricity. Heat was such an issue that each of ENIAC’s units (referred to as panels by the university, but units by the military) had a thermostat, fans, blowers, and vents. Any given unit would automatically be shutdown if the temperature exceeded one hundred fifteen degrees Fahrenheit. With its immense size and appetite for electrical power, it read punched cards from an IBM card reader, and its output was produced with an IBM card punch. This setup for input and output forced ENIAC to be a hybrid binary and decimal system. Once the decision was made to use IBM punched cards, the input and output system needed to be capable of decimal, while many other parts of the system were binary. This also meant that “local control” was used. The machine had various coprocessors in certain units to handle specific tasks often resulting from the complexity introduced from both binary and decimal being used simultaneously among other factors. After a given job was completed, the output cards would be run, offline, through an IBM 405, to produce human readable output. As far as performance goes, ENIAC was capable of around five hundred FLOPS depending upon the work load. While this seems very slow today, it was still roughly a thousand times faster than any other machine at that time. In the early days of its service, the machine worked roughly half of any given day, and these breakdowns were almost always due to vacuum tube failures. This was followed by improvements in components around 1948 which increased the mean time to failure to about two days. Despite what seems to modern minds to be an unacceptable failure rate, ENIAC was better than the machines before it, and better than many machines that immediately followed.

Operating ENIAC wasn’t simple, and programming the machine wasn’t recognizably programming to anyone today either. The only people who’d recognize the process are those who worked on later GE and UNIVAC machines, and for them it would still be… somewhat perplexing. First, any given problem would be written on paper, the machine’s plugboards would then be rewired, and the machine’s three function tables with their twelve hundred ten-way switches would be set. Data would be card punched and fed in, and debugging would then commence with the program being walked through instruction by instruction, and finally, the program could be run. This process could consume an entire week of time for a programmer.

I converted a tutorial for programming the ENIAC to PDF from the Internet Archive. If you are on a laptop or desktop computer, I highly recommend viewing it from the web, but on other devices the PDF may be better.

There’s an article on the simulator for which this tutorial was intended, and the simulator itself is available as a Java program, but you will likely require an older version of Java to run it.

ENIAC’s most notable uses were in the development of the hydrogen bomb, but it was in operation until 23:45 on the 2nd of October in 1955 performing a variety of calculations for the US military.

Many of the people who worked on ENIAC went on to have significant impacts in the computer industry, and that is the primary technological contribution of the ENIAC. Given both the machine’s design and constituent components, Eckert seriously wondered why no one had built it earlier. In my opinion, the largest impact of ENIAC was neither technical nor scientific but societal. During its development Vannevar Bush at MIT, Howard Aiken at Harvard, and George Stibitz at Bell Labs all considered Project PX to be a waste of resources and funds, they felt the project would fail, and they felt that further development of proven technologies like relay calculators and differential analyzers would be best. These were incredibly intelligent men, and they were all wrong. Prevailing opinions of the day were clearly against the Project PX members, and their success shifted those opinions quickly and dramatically. When members of the press were invited to the Moore School on the 14th of February in 1946, it was Arthur Burks who was responsible for the demonstration of ENIAC, he says of the event:

I explained what was to be done and pushed the button for it to be done. One of the first things I did was to add 5,000 numbers together. Seems a bit silly, but I told the press, ‘I am now going to add 5,000 numbers together’ and pushed the button. The ENIAC added 5,000 numbers together in one second. The problem was finished before the reporters had looked up! The main part of the demonstration was the trajectory. For this we chose a trajectory of a shell that took 30 seconds to go from the gun to its target. Remember that humans could compute this in three days, and the differential analyzer could do it in 30 minutes. The ENIAC calculated this 30-second trajectory in just 20 seconds, faster than the shell itself could fly.

In newspapers across the USA and Europe, photos of ENIAC and the stories of the miracle machine appeared. The papers chose not to show the people who made and operated the machine, but rather the wires, switches, blinken lights, and panels. The photos showed what people were in them as small and almost fragile compared to the machine in which they stood. The press referred to ENIAC as an electronic brain, or super brain, and even as a wizard. The hype was huge and caused a variety of reactions ranging from excited utopian dreaming to existential dread and fear. Despite the press having attempted to temper these emotions with supplemental articles clarifying that the electronic brains lacked the capability to perform actual thought, anthropomorphism continued. From the dawn of computing, it seems, some have thought that the machines were either more capable than humans or would be so in the near future, and the thought that these machines could one day conquer man was also forming in the minds of many. The ENIAC’s introduction and association with the “electronic brain” label led to the term brainiac for an especially bright, studious, erudite individual; that’s how big the hype was. One more change to the English language was made by ENIAC; no longer would “computer” refer to a person, but ever after it would be a word for a machine. The term operator or sysop came to refer to those humans who operated and maintained the machines, and the earliest of these professionals were themselves former computers.

Much of this earlier excitement both utopian and dystopian was tempered by the 1970s. In the New York Times on the 4th of August in 1971, WD Smith wrote:

The computer has made a significant impact on society, though it has not been as useful as some of its supporters supposed or anywhere near as harmful as its detractors would have people believe... in many business applications the computer, rather than freeing the user, has created restraints. In many instances the user has been forced to view his own world through the wrong end of the telescope.

Of course, not even a full year before this article, Federico Faggin had completed work on the Intel 4004, and the 8008 would be released in April of 1972 kicking of the start of the microcomputer era.

Unlike most of my articles to date, I doubt very much that any of my readers witnessed any part of this article. Some of you, however, have worked at the places mentioned and may have some second hand knowledge of events, or first hand knowledge of the hardware and software systems, all corrections to the record are welcome. Please feel free to leave a comment.