The History of Commodore, Part 1

Chuck Peddle, the 6502, MOS, and the PET

Charles Ingerham Peddle (Chuck) was born on the 25th of November in 1937 in Bangor, Maine to a successful farm machinery salesman and a commercial illustrator. He grew up just outside the city as the second youngest of 8 on a large piece of property his father owned, which later became one of the first shopping centers in the area. While his father had been successful, he nearly died shortly after the second world war having been given penicillin to which he was allergic. His father never fully recovered, and this resulted in Peddle growing up rather poor. They made a living with the land they had. His father was a good shot, and did a bit of poaching. This provided both meat and money. Peddle and his siblings would cut wood, process it, and side buildings. Peddle would also breed and raise beagles on the property in his father’s kennel. As he got older, Peddle always had a job. He was a theater usher, a pick and shovel road worker, and a radio disk jockey. He became a DJ and radio announcer at the age of 14 (a neighbor ran the local station), and he continued that until he graduated high school at 17 while working other jobs. His speech teacher arranged for him to audition in Boston for scholarship. His DJ dream died quickly after he auditioned. The other talent was far better, and this discouraged him. His teachers and neighbors encouraged him to attend college for engineering.

The Korean War ended in 1953, and one of his brothers was a Marine who’d served in the war and been shot. In 1955, Peddle joined the US Marine Corps Reserve. He was at Pendleton for his first year, and he had an aunt and uncle in that area. While there, he was always involved with electronics, radar and similar things. As tensions in Lebanon heated up, his enlistment was extended, and his group was transferred into the infantry. He was a crew chief and then a fire team leader, and he says that he was good at his job in the USMC and that he enjoyed it.

Peddle had very little money, no where close to what would be required for college. His father arranged some assistance for him from friends, and the bank in town had a program for community assistance. The President of the university also granted him a scholarship. With funding secured but little idea as to what specific engineering discipline he’d wish to pursue, Peddle enrolled in engineering physics at the University of Maine. He received good marks for his first two years, and thinking highly of himself he enrolled in an extra course called information theory in his junior year. This class was conducted by a gentleman who’d worked for Claude Shannon at MIT on Project MAC. The course covered how humans interpret information and then proceeded into Boolean algebra, binary mathematics, and other related topics. Peddle graduated from the University of Maine with his bachelor’s in engineering physics in 1959.

Peddle had fallen in love with computing during his course on information theory, and he knew the rest of his life would involve computers. Having been to California while in the USMC Reserve, he’d also fallen in love with California. He knew he’d need some job training as well. This gave him a road map. He needed to work for a company that would carry him to California, train him, and give him a job in computing. He interviewed with General Electric as they were exactly such a company and got the job in 1959. For the first 9 months, he worked for the missile and space division on vehicles, Gatling guns, and re-entry systems. He then began working on quality control systems related to those projects, and this took him all over the country, exposed him to many different companies, and introduced him to punch card systems and the large computer systems of the time. He signed up for the advanced engineering course in Palo Alto, and got a job in the computer lab for a year. He moved to Phoenix after that, and he worked on a paper tape system and the first hard disk system which held five megabytes. He then invented zone recording for hard disks in 1961. In 1963, he worked in the design automation group. The first task he had was a board layout system. He got promoted a few times and saw a dead end approaching, so he got a job as the systems manager for the jet engines group in Evendale, Ohio. This exposed him to the first on-line system with teletypes and BASIC. Peddle then got to teach the first BASIC class at GE. GE engineers were then designing jet engines with BASIC, and this made a huge impression on Peddle.

In 1969, living in Cincinnati and working on GE’s cash register system called TRADAR, a man from Exxon contacted him and his team about automating gas pumps. Peddle realized that distributed computing was the answer to all of these various problems as opposed to centralized mainframe computing with terminals. He made a proposal for such a system that would handle all of these various computing tasks, but GE chose to sell their computing division to Honeywell in 1970.

Peddle wanted to move back to Phoenix and start his own computer company. To this end, he started a company named Intelligent Terminal Systems. His first aim at his new venture was to design a point of sale system. Unfortunately, he was too early, and he was unable to secure funding for this endeavor. Following the failure of his first startup, Peddle was employed to build a typesetting system around the DEC PDP-11. The company started doing the local Cave Creek newspapers and other publications in the area.

Around this time, Tom Bennett was working on an LSI chip for Viatron at Motorola, designed the chip, and was leading the team developing it. Viatron was working on an intelligent terminal that it would lease for $10/mo per unit (around $79 in 2023), but it was a stock fraud. The company had produced a few units, but the intent was generate a ton of cash from investor interest. Get cash from investors they did… millions. Once this fraud was exposed, he was left with a design team and no task. He then set about building a chip to enable a desktop computer.

After Bennett hired Peddle, the two set about work on what would become the Motorola 6800. Bill Mensch was hired to work on process engineering, but he also helped with the design of the circuitry to implement Peddle’s logic around the PIA and parts of the 6800. Their designs were hand drawn on large sheets of paper, these were then colored by the engineers, simulated on mainframe machines, and then converted into masks for lithography.

Peddle then took some of his designs for a computer from his old company, added the 6800 and the PIA, and made a board at his home. He connected this with a keyboard and a Burroughs Self-Scan display. The machine was then demoed to Motorola, and Peddle gave a course to the marketing and sales team on the advantages of the microcomputer. Selling the machine was still difficult, and Peddle then began to travel and give seminars on the 6800 and PIA as replacements for hardware logic circuits. He managed to sell the 6800 to HP, DEC, Bradley, Ford, and Remington Rand among other companies. From those companies that turned him down, the biggest push back Peddle heard was the pricing. He then asked what instructions these companies actually required. Having collected that information, he proposed a smaller, cheaper, simpler chip. The marketing team accused him of attempting to sabotage the 6800, and they succeeded in convincing Motorola of this. Motorola sent him a formal letter stating that he had to stop work on his low cost microprocessor. Peddle responded to this stating that this constituted project abandonment and that his new designs belonged solely to him, and further that he’d do no more work for them.

In 1974, the team in Phoenix was being moved to Austin, and several members of the Motorola design team didn’t wish to go. Peddle was able to get 8 of them to join him. John Paivnen and Peddle had met each other at GE’s Palo Alto computer lab, and Paivnen had a fab company in Valley Forge making calculator ships for Texas Instruments, MOS Technology. Peddle pitched him and Paivnen immediately understood the implications of Peddle’s idea. Paivnen then brought Peddle, Mensch, and the rest of their team to MOS. This new low cost chip was the 6501 and it functioned without error when they received their first silicon without them having done any simulation. According to Peddle, the 6501 (which could be used in boards intended for the 6800) was never meant to sell in volume. MOS was sued by Motorola over the chip despite the two processors not being instruction set compatible. While the legal mess around the 6501 was going, MOS created the 6502. The 6501 sold for $20 and the 6502 sold for $25.

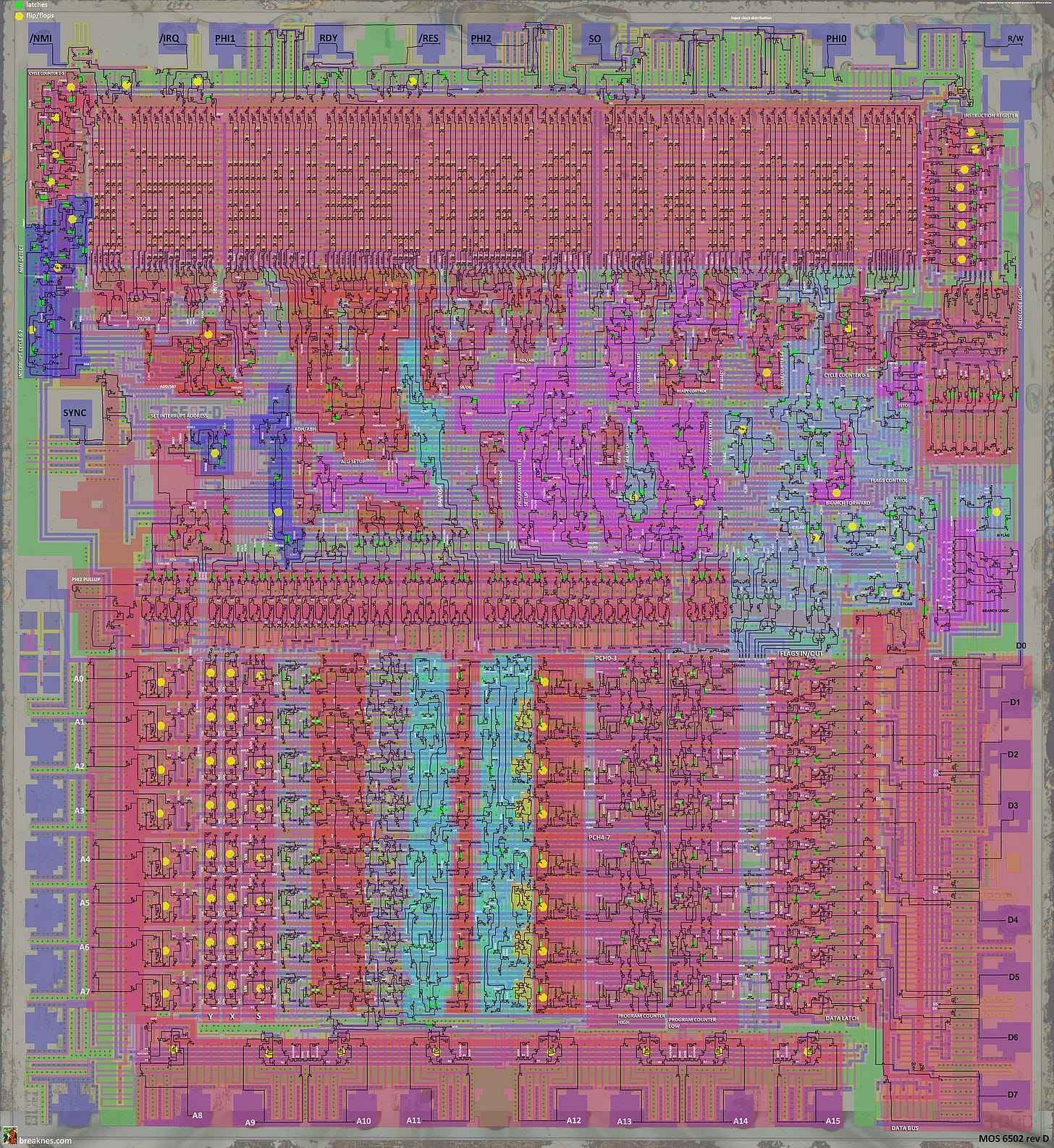

The 6502 is an eight bit CPU clocked at 1 MHz with a sixteen bit address bus and originally built on an eight micron process. The total die size is 3.9 mm by 4.3 mm. The 6502 could support up to 64K RAM.

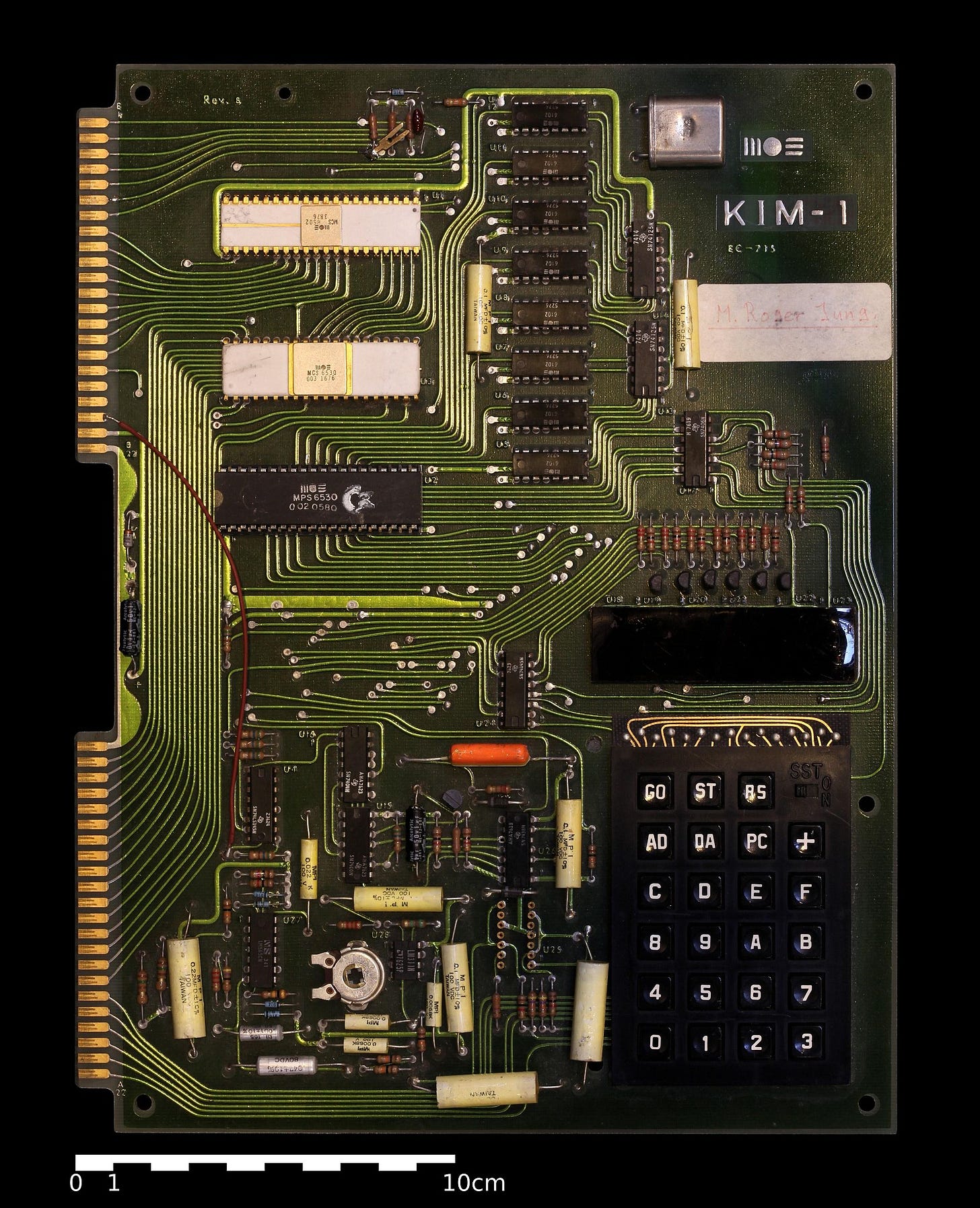

The team needed to generate interest in their new processor, and WestCon (Western Electronics Show and Convention) in 1975 appeared to be the right time and place. MOS were intending to do a sale of their chips at the convention, but shortly after arriving, they were told that they wouldn’t be permitted to do so. They had some folks at their booth who’d direct people to the St. Francis hotel room that Peddle had promptly rented. He and his wife had their chips for sale along with manuals in the room, and they also had the KIM-1 (keyboard input monitor) and the TIM-1 (terminal input monitor). These were the first single board computers.

The KIM-1 sported a 6502 and 1K of RAM with a price of $245. Later versions of the KIM-1 also allowed a terminal to be connected to the board as well as a cassette tape interface for data storage. Tens of thousands of KIM-1s were sold over the years to engineers and college students throughout the second half of the 1970s. Yet, over the years, Peddle had been gathering information from people. What they wanted was a computer that looked like a terminal, was fully integrated, assembled, and could be used independently from other equipment. In other words, people wanted a personal desktop computer. MOS was struggling to make enough money to fund their plans and growth. Atari, Apple, and the KIM-1 were making them a small amount of money, but there wasn’t any major breakthrough yet.

Bill Mensch left the company and went back to Arizona. He started the Western Design Center in Mesa in 1978 and licensed the 6502 design. His new company made a bug-fixed 6502 with CMOS and this was the 65C02.

Jack Tramiel and Manfred Kapp founded Commodore Portable Typewriter Company Limited on the 10th of October in 1958. In the beginning, they were focused on marketing and selling Consul typewriters, but they dabbled in adding machines as well starting 1959. In late 1960, Manfred Kapp was introduced to Willy Feiler. Jack Tramiel then gained the rights to distribute Willy Feiler Zaehl und Rechenwerke GmbH adding machines in North America. This was Commodore’s core business through the first half of the 1960s. Commodore purchased Feiler in 1963 for $1,247,893.72 (around $12.5 million in 2023) with funding from the Atlantic Acceptance Corporation in exchange for selling a stake in what was now named Commodore Business Machines. Commodore quickly setup another manufacturing center in Shannon, Ireland to increase production.

On the 14th of June in 1965, Atlantic failed to meet a matured, short-term, secured note for $5 million (around $49 million in 2023). The company was put into receivership by Montreal Trust three days later. For Commodore, this was a disaster. To cover the capital needed to remain in business, the company sold its Feiler manufacturing plant on the 26th of April in 1966, and they exited the adding machine business. They also found a new investor, Irving Gould. Without money to meet obligations to Gould, Tramiel sold just shy of eighteen percent of the company to Gould for $500000 (around $4.7 million in 2023) with the condition that Gould then became the company’s chairman. Later that year, Commodore entered into a deal with Ricoh to sell rebadged Ricoh adding machines, most notably the 201 and 202.

In 1967, Commodore began a partnership with Casio to distribute Commodore branded Casio electronic calculators. This was quite profitable, and Commodore became popular as a calculator brand. The success in calculators saw the company exit the adding machine business for good in 1969. Commodore was producing its own calculators with its own designs by the 1970s, and they were quickly becoming popular as being high quality with a lower cost than the competition.

In 1975, Texas Instruments, the largest calculator chip manufacturer, directly entered the calculator business. They were able to sell electronic calculators for less than what other companies were paying them for the chips. This severe price cut destroyed many competitors in the market. A usual price for a calculator at this time could be around $400 (around $2288 in 2023). TI was suddenly selling calculators for as little as $50 (around $286 in 2023).

MOS’s primary revenue stream at the time came from selling calculator chips. They too were struggling due to Texas Instruments’ recent entry to the market. With an infusion of cash from Gould, Commodore purchased MOS in exchange for MOS shareholders gaining an equity stake in Commodore with the condition that Chuck Peddle join Commodore as the head of engineering. This move gave Commodore numerous market advantages. Commodore now had shorter turn around time from design to manufacturing, the ability to customize their components and to reduce the total component count, lower overall costs, supply control, and a staff of extremely talented engineers. Having the production plant in Pennsylvania close to the engineering team allowed Commodore to manufacture, test, and revise product samples in less time than many competitors could get a single prototype.

With the calculator industry suffering severely, Peddle convinced Tramiel that he should enter the computer business. At first, they considered buying Apple. Peddle saw a demonstration of an Apple II prototype, but the Steves wanted a little too much money. In 1976, Tramiel gave Peddle a six month timeline to produce a computer in time for CES in January of 1977. Peddle essentially modified the KIM-1 to produce the computer in the time given. This computer became the Commodore Personal Electronic Transactor 2001, or as it is more commonly known: the PET.

The PET was released in June of 1977 for a price of $495 (around $2514 in 2023). This machine had a built-in, nine inch, black and white (1 bit color), CRT display, a tape drive, and a chiclet-style keyboard. It featured 4K static RAM, and it could display forty by twenty five characters at one time. Graphics on the machine were accomplished via the PETSCII character set which was printed on the keys, but the PET lacked any true graphics mode. The data transfer rate for the tape drive was 1500 baud. In practice, however, the baud rate was 750 due to data being written twice to ensure complete/safe writes. The operating system itself required 1K RAM, and one screen’s worth of text required a full 1K as well. So, program logic written by any user would be required to fit in around 2K.. There was no audio in the original PET unless a user connected a speaker to the MOS 6522 CB2 pin with another wire going to ground. For expansion, the PET had four ports. It sported one for memory expansion, one for a second tape recorder, one IEEE-488 parallel port, and one user port (MOS 6522). This computer weighed in at forty seven pounds.

With Peddle’s previous experiences with BASIC, the PET shipped with Microsoft BASIC on ROM. This actually hurt Microsoft quite a bit, as they’d spent the money on development but only received any compensation after the machine saw sales. Making this situation worse, Commodore has the distinction of being the only company to ever have a perpetual and unlimited software license from Microsoft. Even after the wait for Commodore to ship units and receive payment, the payment to Microsoft would be only a one time thing. Microsoft was involved in a lawsuit with MITS over Altair BASIC that was depleting their finances as well making this whole situation rather badly timed. Fortunately, Microsoft’s deal with Apple for AppleSoft BASIC remedied both cash problems. The BASIC ROM was 8K in the original PET, the KERNAL which handled hardware and timing was another 8K, and the character set took 4K bringing the total ROM size to 18K.

Commodore was only able to produce around thirty PETs on any given day with orders coming in for around fifty per day. With low production and high demand, the computer was back ordered for months. The price was increased to $595 (around $3022 in 2023) as orders continued to pour in despite the production issues. Commodore also began selling an 8K RAM version of the PET at a higher price of $795 (around $4037 in 2023).

The 8K version (with BASIC 2.0 installed) could also support a five and a quarter inch floppy disk drive. The floppy drive was external and required its own power. This was essentially an entire computer complete with its own 6502, RAM, ROM, and I/O controllers. The PET would send commands to the disk drive, the disk drive would execute them, and then send the results back. The disk drive could be attached to many PETs simultaneously with daisey chaining.

Commodore expanded to Europe in 1978 and doubled the price of the computer despite only changing the power supply and rebadgeing the machine as the Commodore PET 3008, 3016, and 3032 for the UK/EU markets (the 8, 16, and 32 referencing the RAM amount in kilobytes).

A major complaint about the PET is the keyboard. Not only does it have chiclet-style keys, but it’s small. A modern iPhone Max will cover the main keyboard, and an Apple ten-key-less keyboard will more than cover the keyboard plus the ten-key of the PET. The keyboard also isn’t offset in anyway but are instead arranged as a grid. In fairness to Commodore, most buyers would have had little to no exposure to computers or keyboards, and therefore would have had no expectations. When the 4000 series launched, the keyboard issues were largely corrected. The keyboard was widened, used a staggered layout as opposed to a grid, and the keys themselves were larger. The 4000 series (4016, 4032, 4096) also included a speaker, a plastic case instead of metal, and a twelve inch screen (often green phosphor). These were followed by the 8000 series which had an eighty column display, came with 16, 32, or 96K RAM, but were otherwise the same as the 4000 series. The SuperPET featured eighty columns, BASIC 4.0, a twelve inch CRT, an RS-232 port, and a Motorola 6809. This machine provided a language monitor, APL, BASIC, FORTRAN, Pascal, COBOL, and an Assembler. Programs could be uploaded to another computer via the RS-232 port. The final versions of the PET were known as the CBM line. These detached the keyboard and screen from the computer. With two display modes across the PET line, the forty column and eighty column machines’ programs typically were not cross compatible.

On a side note, I now have readers from many of the companies whose history I cover, and many of you were present for time periods I cover. A few of you are mentioned by name in my articles. All corrections to the record are welcome, feel free to leave a comment.