The History of Microsoft Encarta

Searchable Human Knowledge

In 1985, shortly after the release of Windows 1.0, Bill Gates set Min Lee on a mission to find a partner for a digital encyclopedia product that would serve as a reference companion to Microsoft’s productivity applications. Lee then approached Britannica, the undisputed leader in the encyclopedia market, who’d recently released a new version of the fifteenth edition of their encyclopedia. Microsoft proposed a partnership to produce a multimedia CD-ROM version of the Encyclopædia Britannica. In exchange for non-exclusive rights to Britannica’s text, Microsoft would pay Britannica a royalty on each copy of the CD-ROM product sold. Britannica immediately declined Lee’s proposal. Britannica’s director of public relations at the time, Larry Grinnell, said:

The Encyclopædia Britannica has no plans to be on a home computer. And since the market is so small, only 4 or 5 percent of households have computers, we would not want to hurt our traditional way of selling.

While this might seem insane now, this was not at all insane in 1985. Home computers weren’t yet common, and computers capable of any sort of multimedia were even less common. Microsoft was a much smaller company than it would be in a few short years, and it was a company known primarily for BASIC and MS-DOS. Britannica had no readily apparent reason to fear competition from Microsoft and little reason to desire a partnership with a young company. Britannica was the encyclopedia. They controlled the market, charged extremely high prices, and had strong and stable profits. Britannica was also a company that was led by its sales organization. Traditionally, encyclopedias were something sold not bought. A person didn’t walk into a bookstore and buy the set; a door-to-door salesman showed up.

For Britannica, losing its sales people was a real fear. Would they defect if they learned that a cheaper product with the same information was being sold? Would they wish to be associated with a CD-ROM product instead of the stately and serious books they were selling?

Also in 1985, Grolier’s released two electronic forms of its own encyclopedia. They released Knowledge Disc: The World’s First Laser Videodisc Encyclopedia as well as New Grolier Electronic Encyclopedia. These were both text-only. The Knowledge Disc was a laser disc as the name implied, and it was intended for use in schools. The Electronic Encyclopedia was on a CD and intended for use with IBM PC compatible computers running MS-DOS.

Having been refused by Britannica, Microsoft turned to World Book who likewise rejected them. This search went on for four years until Microsoft was able to strike a deal with Funk & Wagnall’s which was nearly bankrupt at the time. With the deal in place, Microsoft began project Gandalf. Whether in hope of remaining competitive with Grolier’s or something they’d intended but chose to keep secret, Britannica did release their own multimedia CD-ROM encyclopedia in 1989 under the Compton brand name. The Compton product was a free add-on to print encyclopedias from Britannica, but a standalone CD-ROM version retailed for $895 (around $2221 in 2023).

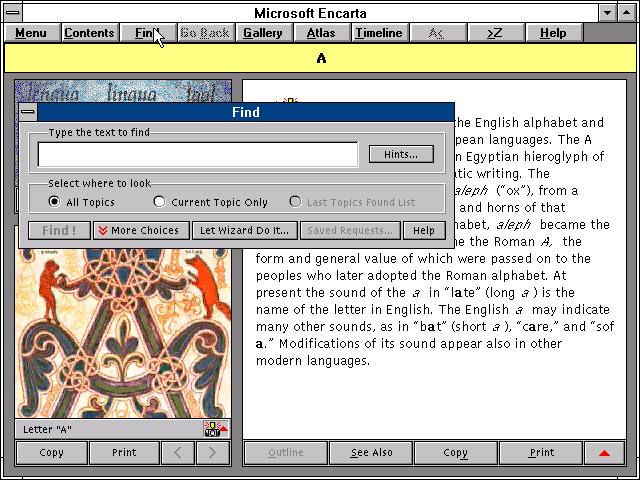

The Funk & Wagnall’s name wasn’t well regarded so the Gandalf team knew that it wouldn’t be part of their own product’s name. Lee, Gates, and the team also knew that simply putting the text on a disc wasn’t enough. This would be a new kind of encyclopedia with search, hyperlinks, graphics, sound, video, and interactivity; an encyclopedia designed with images, illustrations, and maps in mind from the start. Despite having both passion and ambition, this was a relatively high risk project and the team was small. When the project had first started, printed encyclopedia sets generally sold at a price above $1000 (nearly $3000 in 2023). With Grolier’s and Compton’s both having been on the market, the common price had steadily fallen to just under $400 (around $941 in 2023). The profit that might have been was clearly reduced, and a race to the bottom had begun. Until October of 1991, project Gandalf’s team had consisted of fewer than 4 full-time employees at any one time. This started to increase as the project took more form, and the editorial team at Microsoft became the largest editorial team of any encyclopedia publisher over the product’s lifetime.

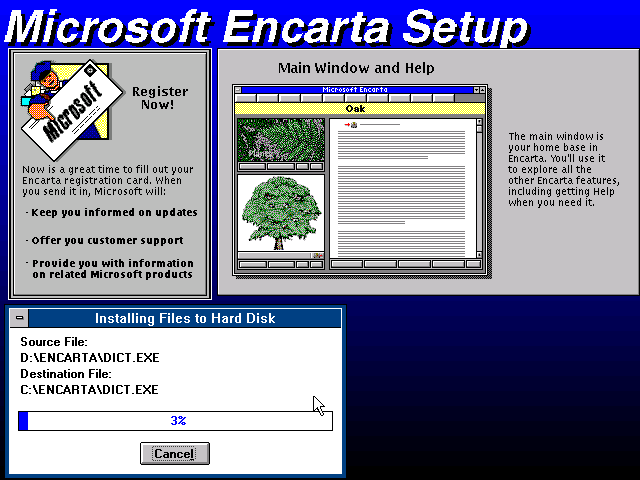

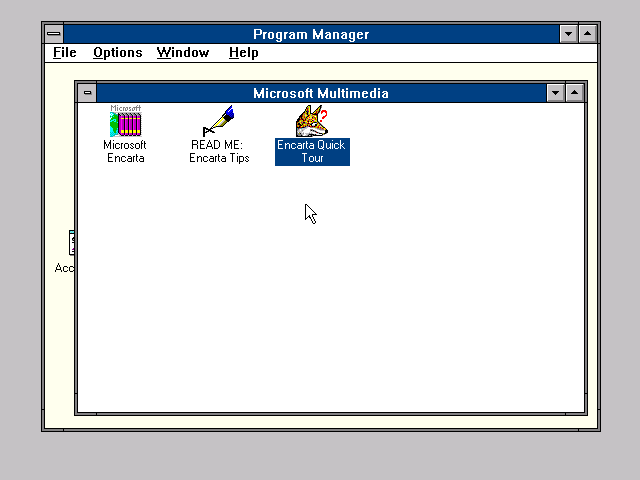

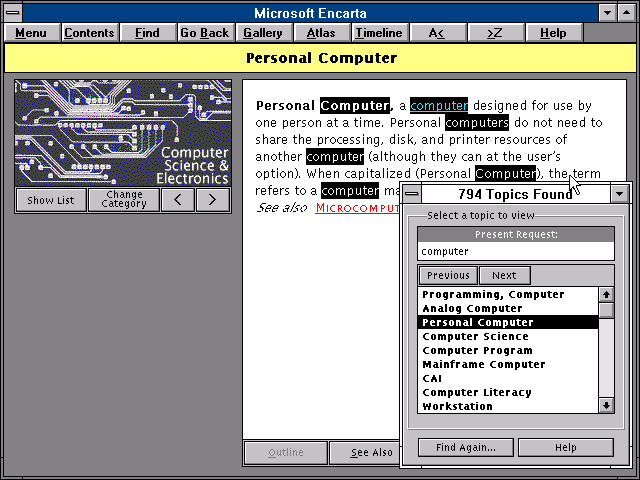

To make this encyclopedia work, several DLLs were created in C that extended Multimedia Viewer. These were then used with SGML text files and an Access database. The resulting product was Microsoft Encarta which included fourteen thousand media elements, five thousand photos, one hundred animations, and seven hours of sound. Getting all of this together was a difficult process for the team. For each image, animation, or audio clip included, something had to be removed. CD-ROM storage is very much a zero sum game.

At launch in March of 1993, Encarta was $395 (around $841 in 2023). Over the first six months following release, it gained just three percent market share. Compton’s had reacted to Microsoft’s entrance by dropping their price to $129 (around $274 in 2023) for anyone who claimed to own a competitor’s product. Retail outlets didn’t exert much effort to have customers prove the claim, and Compton’s started to sell very well. The Encarta sales team was eager to drop the price to compete, and Encarta was then sold at $99 (around $210 in 2023) for the holiday season. By the year’s end, Encarta was the best selling CD encyclopedia on the market with more than three hundred fifty thousand copies sold. Encarta quickly became a product bundled with multimedia PCs, and revenue was brought in as people bought newer editions. This first edition was followed by the “1994” edition later in 1993, and a release was made yearly thereafter. For many people, Encarta was the first practical reason to purchase a CD-ROM drive for a computer. While audio CDs had been introduced in Japan in 1982 with Europe and North America following in 1983, they didn’t overtake vinyl in the USA until 1988. CDs surpassed audio cassettes in 1992. With Encarta and then Windows 95, CD-ROM became normal in the world of PCs.

This was a devastating blow to print encyclopedias. In 1990, Britannica’s annual revenues were $650 million (about $1.5 billion in 2023). This figure dropped to $345 million for 1996 (around $677 million in 2023). Britannica sold the Compton’s digital product line to the Chicago Tribune for $57 million in 1993 (around $112 million in 2023) as they had finally relented and released CD-ROM version with their primary brand for $1200 (around $2492 in 2023). This failed and the price was dropped to $995 in 1995 (around $2009 in 2023). The sales force was furious, the product didn’t sell despite the price reduction, and in August, Britannica closed two-thirds of its sales offices. It launched a web version of its product in October. By December, things were bleak and a sale of Britannica to Jacob E. Safra was announced the 19th of December in 1995.

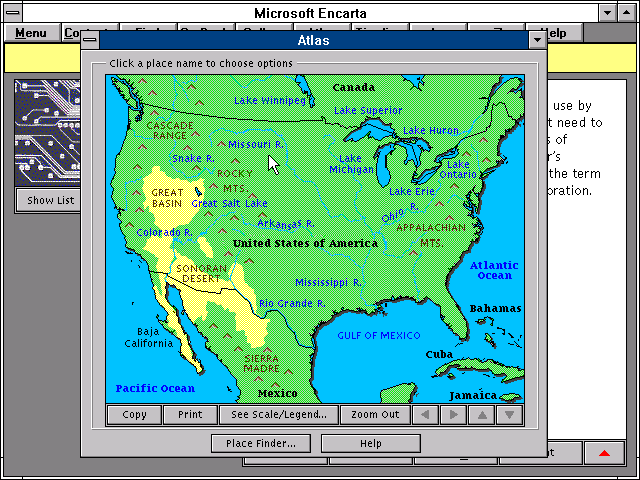

While Britannica was imploding, Microsoft’s efforts were going strong. Encarta was ported to the Macintosh in 1994. Encarta Atlas was introduced in 1995 and the product was made fully 32 bit using C++ and MFC. In 1996, Encarta expanded to two CDs. This again posed a difficult challenge. Stub articles had to be added to the first CD, and then upon clicking to expand an article the user was prompted to switch discs. How does navigating backward happen? Does the user get prompted to switch discs again? Does the user get a stub? Should the prior article be cached? When is any one of these options appropriate? All difficult choices. Figuring out when and where to make this happen wasn’t easy. Disc swapping was later ameliorated as hard disks grew in size and full installation became possible, but this wasn’t yet so. A virtual globe was added in 1997. Through the late 1990s, content was added to Encarta from both Collier’s and New Merit Scholar’s encyclopedias as Microsoft gained the rights to their respective texts. In 2000, Encarta became available on the web. Full access to the web was restricted to paid subscribers with a smaller subset of the encyclopedia made available to all. This also provided article updates to locally installed versions if users wanted it and had a subscription. 3D Virtual Tours were added to Encarta in 2001. Interestingly, Encarta was also available in Windows Live Messenger via encarta@conversagent.com or encarta@botmetro.net. Over the lifetime of Encarta, the encyclopedia expanded to 5 CDs or a DVD. The product was also available in three versions: Standard, Deluxe, Reference Library. The technical side of the program also changed to web technologies (Trident, HTML, CSS, Flash) and C# over time despite being available entirely locally on DVD. The team approached programming technologies very pragmatically attempting to choose the right tool for any given task as opposed to dogmatically choosing a single tool.

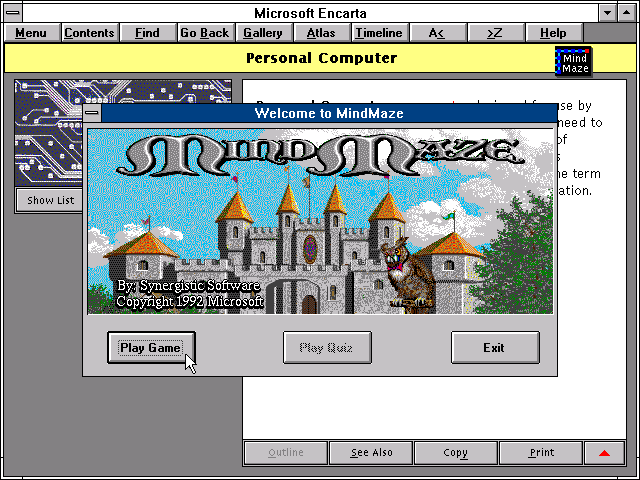

Unlike many products, Encarta’s ship dates were fixed. The product always had to be ready for “back to school.” Yet, this was also a product shipped on read-only media before cheap internet access existed, and therefore showstopping bugs couldn’t be present. When bugs did ship, they were often known to the team. So, if you walked through a wall in the Parthenon, the team knew this could happen. The key was that a bug couldn’t be so bad that it ruined the experience. The product was extremely rich in visuals, audio, and interactivity and therefore it could be (and by many on the design team certainly was) considered a work of art. People on the team lost hours over single pixel imperfections, over sluggishness or glitching in palette swapping, and over bugs in navigation history. People on the team would sometimes work for twenty four hours straight and sleep at their desks in attempts to get things ready to ship, and often enough entire articles or even features had to be pushed to a later edition.

Despite the Encarta team having grown and become international with localization teams around the globe, Encarta wasn’t a massive source of revenue for Microsoft. It had a large amount of overhead and the educational market was rather thin. Many of the people on the team could have received pay raises or promotions rather quickly if they’d transferred to other teams, but the Encarta team had rather low turnover. The sense that I get is that this was quite a dedicated team who enjoyed the work that they were doing and the product that they made. Several members mentioned that a rather serious occupational hazard was getting lost in content while working. They’d be editing something or testing something and find themselves having lost an hour just reading the encyclopedia they were working on, an eerily modern and relatable issue.

On the 9th of March in 2000, Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger launched Nupedia. This was an online encyclopedia where articles were written by volunteers who had subject matter expertise (with preference for PhDs). Those articles were then reviewed by editors, and approved articles were subsequently published online and licensed as free content. Apparently, encyclopedias are difficult to make. In it’s first year of operation, Nupedia had only 21 articles. On the 10th of January in 2001, Sanger proposed a wiki that would server as an upstream content source for Nupedia. Wikipedia was launched on the 15th of January in 2001. Wikipedia’s growth was explosive. In its first month, it gained 200 articles. By January of 2002, Wikipedia included more than 20000 articles. Nupedia was dissolved in September of 2003 following a server crash.

Microsoft had completely revolutionized and democratized the encyclopedia market, made CDs common, and made human knowledge searchable. Unfortunately, Wikipedia continued to grow, and Encarta sales declined. Encarta was discontinued on the 31st of October in 2009.

Many reasons are given for Encarta’s demise. Wikipedia’s effect on the market cannot be discounted, but it also wasn’t the only cause. Google offered Wikipedia results and many more sites besides. People paying for an internet connection could simply search a topic or a question and be presented with millions of potential information sources. Personally, I find this disappointing. Encarta’s information was more engaging and more fun to explore. There were many rainy days in my youth where I could be found exploring Encarta 94 or 97. Encarta also had a better user experience than the web. There weren’t banner ads, pop ups, cookie notices, donation requests, or any other annoyance. A person could simply use a searchable, linked, multimedia encyclopedia.

I now have readers from many of the companies whose history I cover, many of you were present for time periods I cover, and a few of you are mentioned by name in my articles. All corrections to the record are welcome; feel free to leave a comment.