The History of Red Hat

The Billion Dollar Open Source Company

Bob Young was born in 1954 in Hamilton in Ontario, Canada. He grew up with his grandmother living next-door to him, his parents, and his siblings. After school, his grandmother’s housekeeper would have freshly baked cupcakes for him and his three brothers. He played sports as a kid and he enjoyed it, but according to him, he wasn’t any good. After grade school, he attended Trinity College School in Port Hope, and he later attended Victoria College at the University of Toronto where he received his Bachelor of Arts having majored in history. Young says that he was “a terrible student.”

Young felt that having a degree in history was somewhat useless as far as job prospects go, especially so with poor marks, and he knew that starting a business would provide him a job. Young referred to himself as “an unemployable idiot,” and felt that starting a company was lower risk than seeking a job elsewhere, so, Young started a typewriter rental business. His office was outside of Toronto next to a factory farm that raised fishing worms. After a time, this business ceased doing well as word processors and computer terminals began to proliferate. Young then started a computer rental business called Vernon Computer Rentals. This did well until the 1989 recession. Young sold the company to Greyvest Capital for about $20 million, which put about $4 million in Young’s pockets. As a result of this deal, Young had to stay on and invest some amount of that money into the venture. A few months after this, Greyvest was in bad shape, its stock plunged, and Young held shares in a worthless company. Young was eventually laid off.

In March of 1993, Young was unemployed with a wife and three children, a mortgage, and a net worth that was near zero. While not a highly technical person himself, he was definitely in the industry with his former venture, and he felt that there was an opportunity with open source software and Linux. He started a new company called the ACC Corporation (name chosen so that it would appear near the front of a phone book) where he sold software on CDs via a catalog. Slackware was apparently among those offerings along with other open source software. He also resold UNIX and some other proprietary software. At this time, a person would need to download dozens of floppy disk images or one large CD image when it came to Linux. Given that modem speeds were slow the download would take considerable time. CD burners were also quite expensive in 1993 with the first burner below $1000 still being two years in the future. Due to these factors, there was a small market for premade open source software CDs. At this time, he was operating from his wife’s sewing closet at their home Connecticut.

Despite selling Linux on CD, Young didn’t fully understand what he was selling. He visited the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland to which he’d been invited by Don Becker.

Becker was working on the Beowulf project, the first supercomputer to run Linux. This was cluster made of off-the-shelf computers. This first cluster wasn’t really much, sixteen 486DX4 computers connected to one another via bonded ethernet. NASA needed a gigaflops-capable workstation for less than $50000 (this would be around $105000 in 2023), and they needed software to which they had modification rights. Beowulf solved both of these issues. The key advantage of Linux in this scenario was its open source nature. While Becker and his colleagues all felt that Solaris was the superior UNIX product, they didn’t have the rights to modify it for their needs, and as a result they chose Linux. Young realized, seeing Beowulf, that Linux was more than just another UNIX.

Marc Ewing was born on the 9th of March in 1969, and is the son of an IBM programmer. He was an entrepreneur by the age of 10. He played the saxophone, and he’d fill his saxophone case (emptied of its erstwhile contents) with Bubble Yum and Bubblicious purchased for a quarter a piece at local drugstore. He’d carry the gum-loaded case to school and sell the gum for a dollar at lunch. He was the gum smuggler of Hagen Elementary in Poughkeepsie, NY. He attended computer camps as a child where he learned how to write software for Apollo and Commodore computers. He graduated from Carnegie Mellon University in 1992 where he’d had a penchant for wearing his grandfather’s Cornell lacrosse cap that happened to be red. He also was usually found in the computer lab. Being rather knowledgeable and skilled while also often being present, other students frequently came to him with questions. He was nice and helpful and people started saying things like “look for the guy in the red hat” when anyone needed help.

Following college, Ewing did a fairly brief and “pretty boring,” according to him, stint at IBM. After leaving, he needed a way to pay rent. He wanted to do some hacking and needed a cheap UNIX, and there was this new Linux thing around. So, in 1993, he started Red Hat Software from his apartment in Durham, NC. He shared this apartment with his new wife, Lisa, whom he’d met in elementary school when she bought gum from him.

The first release of his Linux distribution was called Red Hat Software Linux, abbreviated to RHS Linux in manuals and related documentation. The distribution was built around the package manager RPP, and it shipped on a single CD with a plain, solid-red label. When shipped, the software was accompanied by a letter thanking the customer for purchasing the beta version of the software, and it was signed by Marc Ewing and Damien Neil (the first employee, who was an intern). This preview release shipped with the Linux kernel version 1.1.18 on the 29th of July in 1994 and it had no version number.

The second release was the first to be widely circulated. This is known as the “Halloween release” and was version 0.9 on the 31st of October in 1994. This was still a beta, and users could chose kernel version 1.0.9 or 1.1.54, the latter being a development version. In this release, users were encouraged by the documentation to use a graphical package manager front-end to RPP written TCL/TK called LIM (Linux installation manager). This release received praise for having a number of graphical system management tools: users, groups, package management, filesystems, time/date, networking, and so on.

Linux news groups were buzzing about this release, and that buzz caught the eyes of Young. Young owned a couple of mailing lists for “New York Unix and Linux Journal” and was trying to leverage those to promote his catalog. At this point it carried Yggdrasil, InfoMagic, and Slackware among smaller titles, and these were listed for between $20 and $50 (around $42 to $105 in 2023) which gave him a around a fifty percent margin. Sales were picking up, and customers were talking about Red Hat. By autumn of 1994, seeing Red Hat mentioned in news groups and his customers talking about it, Young decided it was time to reach out to Ewing. He was selling roughly a thousand or so copies of various Linux distributions each month, and felt he could sway around ten percent of his customers to give Red Hat a try. Young figured he’d ask Ewing for a ninety day supply, or three hundred copies. Young called Ewing sometime in September with the intent to get Red Hat Software Linux added to his “ACC PC Unix and Linux Catalog.” This ask for three hundred copies didn’t sit well on the phone call. Young got silence for a good and uncomfortable amount of time. Ewing eventually replied and told him he’d only really been thinking about making three hundred copies total.

Ewing needed finance and marketing help, and Young needed a product that he could sell as his own. The two negotiated back and forth finally reaching an agreement in January of 1995. Young bought the copyright, the brand, the trademarks, and in return Ewing received shares in ACC Corp which was now Red Hat Software, Inc (prior to this RHS was a sole proprietorship under Ewing). Ewing was happy to be rid of sales duties, and Young was happy enough to have those duties. They both actually needed financial help. The strategy at this point was just to get credit cards, max them out, and keep moving. Some amount of credit would be used to pay pre-existing debt service and the rest to fund the company. Young eventually had to turn to his wife, Nancy, as she had better credit.

Without my wife Nancy’s sterling credit rating, I wouldn’t have been able to raise the money that got us to profitability.

They were still working out of Ewing’s apartment after forming the new company, and they’d take group trips to Sam’s Club for soda. During one such trip, a toilet in the apartment overflowed in the early morning and started leaking into the unit below. Maintenance was called and no one was there. There were many computers, but no people. They were kicked out. The company then relocated to a small business office in the area.

The first release of RHS Linux under the newly formed corporation was the “Mother’s Day” release in May of 1995. This was version 1.0 and shipped with the 1.2.8 kernel. The name was now “Red Hat Commercial Linux,” and the logo had changed from a tall, red, top hat to a man walking, carrying a briefcase, holding onto a red hat.

Later that summer, RHS pushed out a bug fix release known as “Mother’s day plus one.” This shipped with kernel 1.2.11 or 1.2.13 depending upon when a customer purchased it.

Red Hat was getting big for a Linux outfit despite being very small. Slackware was still the king with the estimate by Young being around ninety percent of the overall market. Yggdrasil was estimated by him at around five percent, and SuSE was a decent player (at this time essentially a Slackware derivative). Young knew why this was. Distributing on CD was great for those who had slow internet connections, which was everyone, but it sucked for updates. By the time the CD was in someone’s hands it was out of date. As a result of this, Red Hat’s Linux needed to be remade so that it was FTP-friendly, as Slackware already was and essentially had always been. The solution to this was RPM initially written in Perl by Ewing and Erik Troan.

The first release to use the Red Hat Package Manager (RPM) was the 2.0 beta in later summer of 1995. This was also the first release from Red Hat to use ELF binaries instead of a.out. The final 2.0 release would be in early autumn of 1995, and this changed the branding to “Red Hat LiNUX.”

Red Hat was growing quickly and gaining both market share and mind share. Their final release for 1995 was version 2.1 “Bluesky” for which DEC did a promotional CD release for x86 as a teaser for the upcoming “Red Hat Linux/Alpha 2.1” that would see release in January of 1996.

By the end of the year, Young’s credit card debt was at around $50000 (around $98000 in 2023), but they finally reached profitability. I am certain that Nancy was pleased as Red Hat paid off the credit cards.

On the 15th of March in 1996, Red Hat released version 3.0.3 “Picasso.” This was the first version to have simultaneous release for more than one architecture. Red Hat was available for both DEC Alpha and Intel x86. The Alpha version was interesting in that it used a.out while x86 used ELF, and the Alpha version was statically linked (no shared libraries). This version also saw the first appearance of Metro-X from Metro Link Inc in Red Hat Linux. At this time in the Linux world, the configuration of the X Windows server was something like a mixture of cleromancy and sisyphean labor. Metro-X replaced parts of XFree86 and provided a graphical configuration tool for X setup. Branding for 3.0.3 was a bit muddled. This release was variously branded as Official Red Hat LiNUX (emphasis was Red Hat’s), Red Hat™ Software Inc LiNUX, RED HAT LINUX, and Red Hat Linux. This is due to lower cost and/or free redistributions of the system already beginning to proliferate. Red Hat Software felt that they needed to differentiate their release from these redistributions.

The months between March and August of 1996 were busy ones. Red Hat Linux was starting to become a recognizably modern Linux distribution through this time. In the run up to 4.0, Red Hat rewrote RPM in C, started working on Pluggable Authentication Modules (PAM), started replacing TCL/TK tools with Python/TK tools (starting with network configuration), and began migrating to Linux kernel version 2 which brought kernel modules with it. The 4.0 beta was referred to as “Rembrandt” and would see the final beta release in August of 1996.

On the 3rd of October in 1996, Red Hat released version 4 “Colgate” for Intel x86, DEC Alpha, and Sun SPARC. This release saw Alpha get ELF binaries and dynamic linking. Version 4 moved to kernel version 2.0.18, and it provided the Red Baron web browser derived from Spyglass’s product. For the first time, Red Hat also provided free electronic documentation in addition to the dead-tree format that always came in the box. On the branding side, this release was also the debut of the Shadowman™ logo. Colgate gained acclaim as Info World’s best operating system of 1996.

In these early days, Red Hat didn’t really have much of a business model. They sold their software in big boxes, and these boxes found their way onto store shelves, or they were ordered from Red Hat directly, or they were purchased through catalogs. The usual price in a bookstore or computer store was $29.95 (around $58 in 2023) and these sales were motivated by people not wishing to download the operating system and accompanying software, create the install media, and then do the installation. With software in a box, they could simply insert the disc and proceed. The box also provided documentation.

This was a small struggle between me and my father. In a MicroCenter store in Cincinnati, I saw Red Hat. I had used Slackware at home on a hand-me-down computer, and it was fine. The issue is, my knowledge of the system was lacking as was my modem speed. Downloading those floppies took a very long time. I asked my father to buy me a copy of Red Hat, and he said “why would you pay for free stuff?” My answer was documentation and download time, and I pushed the educational aspect of the documentation. I didn’t immediately win. Over the next year or so, I would ask for a copy of Red Hat every time I saw one while we were out and about. My father eventually relented. This was a big deal despite no one realizing it at the time. My entire career was started from a Red Hat manual.

At the same time, Red Hat was doing paid phone support for a handful of customers. This was a very small part of the business in the 1990s, but it was one that Red Hat felt was important as a differentiator in the market. They also knew that this particular model wouldn’t scale very well. To put this in perspective, NT was still a new product in the 1996 time-frame and wasn’t yet the market force it would later become. The primary competition that Red Hat faced was commercial UNIX. Compared to commercial UNIX companies, Red Hat’s price was lower, but it didn’t have the same level of support, it didn’t have custom servers and workstations, and it didn’t have the staff to provide any of those things or even to work on them. While Red Hat had turned a profit, it was still selling a product that could be had for free. The value-add that they could provide was rather small. Things like a proprietary web browser, documentation, and phone support were great, but they wouldn’t work forever.

On the 3rd of February in 1997, Red Hat released a bug fix version 4.1 “Vanderbilt.” This release shipped with kernel 2.0.27. In May of that year, Red Hat released version 4.2 “Biltmore” and this was the last to ship with the Red Baron browser. Later versions that year (4.8 through 4.96) shifted the distribution to glibc 2.0 and also moved the development model to public betas in a major way.

On the 1st of December in 1997, Red Hat released version 5 “Hurricane.” This name comes from a hurricane that hit Red Hat’s home town and did a large amount of damage to the area, but spared Red Hat’s HQ. Hurricane included Real Audio™ client and server software among other proprietary software add-ons, and was named Info World’s best product of the year for 1997.

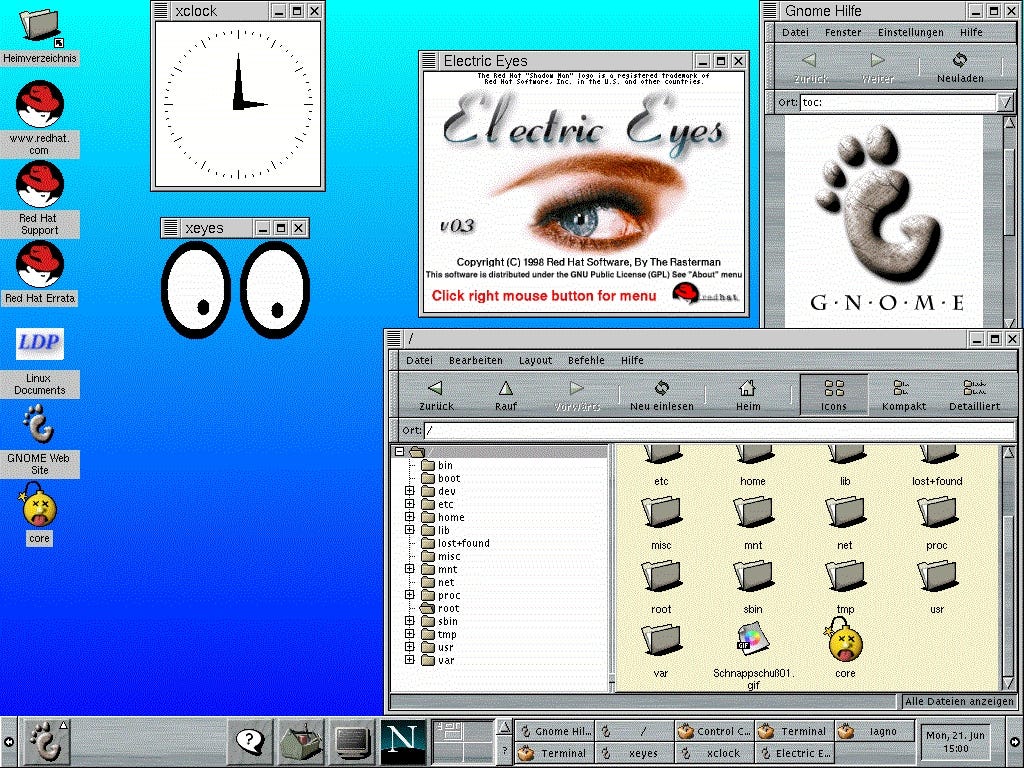

Red Hat Linux 5.1 “Manhattan” was released on the 1st of June in 1998. This release doubled down on proprietary add-on software including an extra CD for just those applications. A preview release of the GNU Network Object Model Environment (GNOME) was included in a separate directory on the installation media as well. Manhattan was the first release to include linuxconf as a centralized configuration tool. In the realm of accolades, 5.1 received the PC Magazine Technical Innovation award, and both the Editor’s Choice Award and the Just Plain Cool Award from Australian Personal Computer magazine.

In September of 1998, Red Hat was doing quite well. The company was generating around $5 million (around $9.4 million in 2023) in sales per annum. Even in 2023 dollars, that would be a pretty good number for a Linux and free software company. This number was impressive enough to get outside investment from both Intel and Netscape. Other companies came around shortly thereafter, Benchmark Capital and Greylock Management provided venture capital investments, while IBM, Novell, Oracle, and SAP took smaller equity positions. Around this same time, Red Hat increased their support services, and this became a growing part of their business. In November of 1998, Red Hat relocated to an office in the Meridian Business Complex in Research Triangle Park, NC.

In early 1999, things started changing for Red Hat Software, Inc. The company entered into strategic agreements with Dell and IBM to offer Red Hat’s Linux distribution on their servers and workstations as an open source alternative to proprietary UNIX solutions. In particular, IBM would offer Red Hat Linux on their Netfinity servers, PC 300 workstations, Intellistations, and ThinkPads, and Red Hat would offer technical support to customers buying those systems. For Dell’s part, they offered Red Hat Linux on their servers, workstations, and desktop PCs. For Dell, their PowerEdge servers were the biggest money maker. Consequently, Dell made an equity investment in Red Hat, and the company committed to shipping current and future PowerEdge servers pre-installed with Red Hat Linux. The two companies then entered into a global service and support agreement. Not to be left out, Gateway started offering Red Hat pre-installed on computers when requested by customers. Over the course of 1999, Red Hat’s revenues double to $10 million (around $18.4 million in 2023) for the year.

While all of this investment and growth was occurring, the engineers at Red Hat were not idle. Bug fix releases for the version 5 series were released with 5.2 “Apollo” on the 12th of October in 1998, and 5.9 “Starbuck” shipping on the 17th of March in 1999. On the 19th of April in 1999, Red Hat released version 6.0 “Hedwig.” This was the big one. On the technical side of things, this version featured glibc 2.1, EGCS, kernel 2.2, and a fully integrated GNOME desktop. EGCS was a merger of several forks of GCC that provided several enhancements not featured in the mainline GCC: g77 (fortran), P5 Pentium optimizations, better C++ support, more supported architectures, and more operating system variants. The 2.2 kernel offered better performance and stability on systems like Intel’s Pentium series as well as Cyrix and AMD chips. The 2.2 kernel made giant strides with SPARC, SPARC64, Alpha, ARM, m68k, and PPC. In the realm of desktop support, there had been some BIOS implementations that caused problems with booting Linux, and many of these were remedied with this kernel release. The IDE subsystem was moved into a module, which allowed the use of PnP-based IDE controllers, and the kernel could now automatically detect and configure PCI-based IDE cards including the activation of DMA bus mastering to increase performance. As is usual with kernel releases, tons of drivers for various hardware devices were added. All of these various technical improvements are not really what made the 6.0 release big. This was the version that shipped pre-installed on Dell’s machines, and that made Red Hat some serious money.

Red Hat became Red Hat, Inc. and had their IPO on the 11th of August in 1999 with an offer price of $14 (about $26 in 2023). Within Red Hat, people were anxious. Marc Ewing said:

It was a little bit nerve-racking given the state of the market, but we felt we had a unique and compelling story and that we could go out anyway, regardless of what the market was doing. But it was certainly a little bit of a risk, and we were all pretty anxious.

On the first day, the stock closed trading at $52 (around $95 in 2023) for a two hundred twenty seven percent gain. This was, at the time, the eighth largest, single-day gain in Wall Street history, and it gave Red Hat a valuation of $3.5 billion (around $6.4 billion in 2023).

The company logo changed slightly:

Red Hat grew quickly following their IPO. Offices opened in England, Germany, France, Italy, and Japan. The company acquired Cygnus Solutions who made compilers and debuggers for embedded systems, and Michael Tieman, formerly president of Cygnus, took over as CTO. Marc Ewing then led the Red Hat Center for Open Source (a non-profit arm of Red Hat). Red Hat wasn’t done. They bought Hell’s Kitchen Systems who developed payment processing software for ecommerce companies, Bluecurve who made transaction simulation software, WireSpeed Communications who did embedded wireless software, and C2Net Software who made network security software.

Red Hat Linux released 6.0.50 “Lorax” on the 6th of September in 1999. This version’s major change was the system installer, Anaconda. This was either graphical or text-mode depending upon preference and hardware, and it was written in Python. On the 4th of October in 1999, Red Hat released version 6.1 “Cartman.”

Bob Young left the company in November of 1999. Principally, this is because he didn’t really see himself as the CEO of a large and successful company, but rather as an entrepreneur. He felt that his expertise was in starting companies and getting them on the right path. With Red Hat clearly doing well, he felt someone else should take over. In this case, that someone was Matthew Szulik. A few months later, Marc Ewing cashed out and left the company. His financial advisors at Merrill Lynch sent him a bronze bull’s head to welcome him to his new billionaire status, and at this time Ewing was just thirty years old. He chose to devote some time to philanthropy, and after a while he cofounded the Aplinist.

The 9th of February in 2000 saw the release of 6.1.92 “Piglet.” On the 27th of February in 2000, Red Hat released version 6.2 “Zoot” and this was the first release for which Red Hat offered ISO images on public FTP.

Zoot was followed by the 6.9.5 “Pinstripe” release on the 31st of July in 2000.

In September of 2000, Red Hat launched the Red Hat Network. This marks the transition of Red Hat from a boxed Linux vendor to a services company, or more specifically a “Software as a Service” company. The Red Hat network is a subscription service for customers of Red Hat. Subscribers get support services, system updates, and other advantages for a monthly price. Red Hat Linux 7.0 “Guinness” shipped on the 25th of September in 2000 with Red Hat Network support. Red Hat released the 7.0.90 update “Fisher” on the 31st of January in 2001. This update brought the 2.4 kernel with it and was a pretty big deal. Linux kernel 2.4 brought spin locks, multithreaded I/O and networking, journaled filesystems, multi-CPU support, and USB devices. Version 7.1 “Seawolf” was released on the 16th of April in 2001 and was the first version to feature the Mozilla suite.

In March of 2002, Red Hat relocated its company headquarters to North Carolina State University’s Centennial Campus in West Raleigh. By this point, the company had a headcount of 630, and had annual revenues north of $79 million (a little over $134 million in 2023).

Version 7.3 was the last to carry Netscape and shipped on the 6th of May in 2002. Red Hat made one other release on the 6th of May in 2002. Red Hat Linux Advanced Server 2.1 which would later be renamed to Red Hat Enterprise Linux. This version was based upon 7.2 with several fixes from 7.3 integrated. This version was the focus of Red Hat’s efforts in commercial sales and support, and was explicitly supported by many ISVs.

Red Hat Linux 8.0 “Psyche” was released on the 30th of September in 2002. This was the final release Red Hat made in retail boxes, and it was the release that debuted the “Bluecurve” look and feel. This release also saw the debut of GNOME 2, KDE 3.0.3, OpenOffice.org 1.0.1, GCC 3.2, Glibc 2.3, and kernel 2.4.18-14.

Red Hat Linux 9.0 “Shrike” was the final major version of Red Hat Linux, and it was a purely electronic release. This release was on the 31st of March in 2003, and would serve as the basis for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 3. Notable in this release was the inclusion of Native POSIX Thread Library support which was backported to kernel 2.4.20 from kernel 2.5. This release saw one patch update minor version, and then Red Hat Linux came to end.

From this point forward, Red Hat would develop two different Linux systems. One was Fedora Core (now known simply as Fedora), which would be a rapidly iterated release with the latest technologies, and the other would be Red Hat Enterprise Linux which would have a slower pace of development, would have much longer support lifetimes, would be the focus of support services and resources, and would be sold using a subscription model. Once again, corporate allies signed on to support Red Hat with Red Hat Enterprise Linux, most notably: Dell, IBM, HP, Oracle.

On the 19th of March in 2004, a group of open source software developers released CentOS version 3. CentOS was a “bug for bug” clone of Red Hat Enterprise Linux. It wasn’t the first such distribution, but it quickly became the most common and most popular such distribution.

Red Hat was doing well and joined the NASDAQ-100 on the 19th of December in 2005. The company continued its history of rapid growth over the following years. The company became the first billion-dollar-revenue, open source company in 2012. The company hit $2 billion mark in 2015, and it hit $3 billion in 2018.

In 2014, Red Hat purchased the CentOS project, and established a governing board for CentOS. The lead developers of the project became employees of Red Hat under the Open Source and Standards team.

With its largess, Red Hat either created or significantly supported numerous open source software projects, notable among these are: KVM, GNOME, systemd, PulseAudio, Dogtail, MRG, Ceph, OpenShift, OpenStack, LibreOffice, Xorg, Disk Druid, rpm, SystemTap, NetworkManager

On the 28th of October in 2018, IBM announced its intent to acquire Red Hat for $34 billion and operate the subsidiary out of their Hybrid Cloud Division. The US Department of Justice approved the deal on the 3rd of May in 2019, and the acquisition was completed on the 9th of July in 2019. While this was obviously an extremely important moment for Red Hat and Red Hat’s customers, it cemented the victory of open source and Linux in the enterprise world. Linux was so clearly a dominant player in the server market that the corporate computing company purchased the largest Linux and open source company.

In true IBM fashion, there could be no competition with their enterprise offering, and CentOS was killed on the 8th of December in 2020 with the final version being CentOS 8. In its place, IBM announced CentOS Stream which is effectively a rolling release preview of Red Hat Enterprise Linux. In mid-June of 2023, IBM made CentOS Stream sources the only publicly available sources of Red Hat Enterprise Linux. This was a move that attempted to cease open source clones of RHEL such as AlmaLinux, Rocky Linux, and Oracle Linux. Expressly, IBM’s stated terms are that RHEL’s customers could not redistribute RHEL’s sources. This change sparked quite lively debate in the open source and Linux communities. The primary source of debate being that IBM neither owns nor creates much of the software that is shipped in Red Hat Enterprise Linux, and further that much of that source is licensed under the GPL version 3. Under GPLv3 section 2, “sublicensing is not allowed.” Further under sections 3 and 4, the license elaborates that no one distributing a covered piece of software may endeavor to limit operation or modification of that software and that the software may be redistributed verbatim.

Red Hat became the most valuable and profitable open source company despite clone makers. These moves by IBM seem shortsighted to me. Bradley Kuhn of the Software Freedom Conservancy, had this to say:

This is why we call the business model, “if you exercise your rights under the GPL, your money is no good here.” Whether or not this RHEL business model complies with the GPL is a matter of intense debate, and opinions differ, but no one, except Red Hat, believes that this business model is in the spirit of the GPL and FOSS.

In my mind, while a product called Red Hat Enterprise Linux continues to exist, Red Hat is dead. RHEL is effectively just branding for another IBM product. Just as IBM slowly withered after attempting proprietary changes to their PC line, they will likely slowly erode the market share that they had shortly after purchasing Red Hat.

Red Hat was a company that did much to further the software industry, to foster open source software development, and to provide the software foundation of the modern world. They produced a software product that could be relied upon, and all of those who worked on Red Hat Linux should be proud of their achievements.

In the early days, many of us wanted Unix at home. I started with a 286 and DOS with various unix utilities that had been ported. I dual booted with Minix. I still couldn't run most GNU software, including Emacs. I purchased a 486 and tried 386BSD but it didn't work. I downloaded SLS Linux with 0.92 kernel. Slackware was created to fix the bugs SLS wasn't fixing, using SLS's package format.

I became a Unix Sysadmin shortly after. I was installing/using Unix on SGI, Sun (Sun3, Sparc, SunOS, Solaris), DEC (Vax, Alpha, MIPS), HP, Apollo, Cray, Intergraph and IIRC Tektronix. Being able to run a near Unix at home w/o purchasing a $20,000 workstation was huge!

The commercial Unixes for PCs (386 & up) were expensive too. $10,000 IIRC. Linux really had no competition. Solaris for x86 wasn't really available until 2.4 in late 1994 and IIRC you still had to purchase media, etc until Solaris 2.6 or maybe later. By that time, Linux was the preferred choice on x86.

The decision to split into Fedora and Redhat Enterprise Linux probably saved the company. Fedora is free and has all the source that potentially goes into RHEL. RHEL is subscription based and companies renew their subscription to get support. Before that, there were some companies that were buying multiple boxed sets just to support Redhat.

One thing people get wrong is that Redhat has stayed Redhat. IBM expects Redhat to meet financial targets but does not mange how. All the decisions are still made by Redhat. When you say IBM made the decision, it did not.

The decision to stop CentOS was communicated poorly, including internally. I don't want to argue the merits of that.

CentOS Stream was created (poor choice of name IMO) to be in between Fedora and RHEL. Fedora is very desktop oriented and its not used for servers often. Companies were not contributing as much to Fedora and CentOS, which is downstream from RHEL was getting nothing. Stream is much closer to RHEL. As a result, companies are contributing patches and updates and they can now influence RHEL. Which is the whole point of opensource.

5 years after IBM purchased Redhat, IBM had made their money back. They lead their financial results with Redhat. As long as Redhat performs, IBM won't change it because that will wreck it. Redhat is still Redhat culturally and is still making its own decisions.

One of the keys to Redhat is that they always contribute to the upstream products. When they buy a company, like Quay for example, they opensouce its code. They're one of the largest contributors to Kubernetes, which was created by Google. They've created or helped create many foundations that help protect opensource against the patent trolls. I don't think any company has done as much for opensource as Redhat.