The Rapid Rise of eMachines

See what's new in blue

Lap Shun “John” Hui was born in Guangdong, China in 1955, and he spent most of his youth living in Hong Kong. Hui moved to the United States in 1973 to attend the State University of New York at Buffalo. He graduated from the university with his Bachelor’s of Science in Business Management, and he then enrolled at McMaster University in Ontario where he earned his MBA. Along the way, Hui was became a Certified Internal Auditor by the Institute of Internal Auditors and worked as the resident inspector and auditor at Citicorp. Hui chose to leave the financial industry for the computer industry in 1983. His first ventures were with Everex and Techpower which he helped to start and run. In 1993, Hui helped Korean Data Systems establish themselves in the North America by helping them found KDS USA, a US distributor of KDS’s CRT monitors.

In September of 1998, Hui arranged a joint venture between the Korean computer company TriGem and KDS to operate a commodity computer business in the USA called eMachines based in Irvine, California. With the funding, supply, contractual, and legal arrangements all sorted, Hui had to establish retail relationships. Some of these were easier than others. Dedicated computer shops didn’t have much reason to carry a new commodity computer, but they also didn’t have a reason not to do so. A little negotiation, and those were sorted. Others were far more difficult.

BestBuy in particular presented a problem. BestBuy sold a wide variety of products, shelf space in their stores was rather limited, there were a ton of PC manufacturers who all wanted shelf space, and Wayne Inyoue, senior vice president of merchandising at the time, created a value formula to solve this problem. In his formula, every single piece of a PC had a somewhat standardized value including the brand. This allowed them to create a few specific price points with expectations for machines listed at each of those prices. If a machine was made by an unknown brand and wasn’t seriously competitive at a given price point, then BestBuy wouldn’t even give it shelf space. As an example, if you had a 200 MHz Celeron machine from both eMachines and HP and both were $500, the HP would get shelf space, and the eMachine would not. Yet, if the eMachine came in at $350 with those same spaces, BestBuy would carry it along with the HP.

Not coincidentally, eMachines’ own formula somewhat matched that of BestBuy. If the perceived value of a given component was high, and its cost to include was low, it would absolutely be included with the eMachine computer. As eMachines evaluated each price bracket, they didn’t just compare to other computer manufacturers, but also to DIY. They aimed to be cheaper than even the build-it-yourself machine while offering equivalent or better specifications. eMachines managed to grab shelf space at BestBuy and to build machines less expensively than even DIY. The result? By March of 1999, eMachines was the number four shipper of PCs in the USA with ten percent of the market, and the average price for an eMachines PC was under $600 (about $1100 in 2024) with some models selling for as little as $299 (around $550 in 2024). This was a really big deal. From nothing to fourth in a crowded market with Compaq in first place holding thirty one percent of the market, HP in second place with thirty percent, and IBM in third place with eleven percent.

In the first week of August in 1999, eMachines launched the eOne with the first distributor being Circuit City. This was an all-in-one PC with translucent plastics of blue and white. The computer was sold by both Sotec Co of Japan and eMachines, and in the case of Sotac the eOne retained eMachines logo on the side. The sole difference between the Sotac and eMachines versions was only the front logo. The Sotec model said “SOTEC” in the front-center directly below the screen, while the eMachines model said eOne on the front-left directly below the screen. eMachines referred to the color as “cool blue” and not bondi blue, but the colors were close. While the first image below shows the machine slightly darker, that’s due to the lighting. See the second image. According to Stephen Dukker who was the CEO of eMachines at the time, “The chassis design was developed for eMachines under contract to a Japanese industrial firm. It's a different shape, a different color. The only commonality they have is translucency. They are not the same computer. The industrial designs are completely different, and the insides are definitely different.” The designs are… very similar. I will grant that there are noticeable differences, the eOne is taller and deeper, and if you’re doing an all-in-one with a CRT, you’ll have a similar shape overall… but the coloring and the keyboard were just too close. As for the insides being different, absolutely true. Unlike the iMac, the eOne retained a floppy disk drive as well as a serial port, PCMCIA card bus slots, PS2 connectors, RCA out, USB, 10Base-T ethernet, modem, and headphone output. On early models, the eOne also had a parallel port. The computer’s CPU was a 433 MHz Intel Celeron and it shipped with 64 MB of RAM, a 6.4 GB HDD, an ATI Rage Pro GPU, and a 24 speed CD-ROM. The mouse was shaped like a normal mouse, and it had two buttons and a scroll wheel. The price for the eOne was $799 (or $1488 in 2024), but depending upon when and where it was purchased this could be reduced to $399 (roughly $743 in 2024) via a rebate from either CompuServe or AOL. Naturally, the eOne ran Windows 98.

I’m not the only who believed that the eOne was a bit too close to the iMac to be a coincidence. Apple filed a lawsuit against eMachines on the 5th of August in 1999 immediately following the machine’s introduction to the market. The claim was that the eOne violated Apple’s design IP. According to Steve Jobs, “There is an unlimited number of original designs that eMachines could have created for their computers, but instead they chose to copy Apple's designs. We've invested a lot of money and effort to create and market our award-winning computer designs, and we intend to protect them under the law.” The suit was settled out of court with the complete terms not having been disclosed. However, we do know that eMachines agreed to discontinue the machine’s sale, and that Apple agreed to allow them to sell a redesigned eOne. This settlement followed two similar lawsuits having been settled in Apple’s favor, one in San Jose against Daewoo, and another in Tokyo against Sotec.

Riding high on prompt market share acquisition, eMachines purchased Free-PC Inc via stock swap on the 29th of November in 1999. Free-PC was a company that offered, as the name implied, free computers. To do this, the customer agreed to be shown advertisements on the computer. Apparently, no advertisers actually liked this idea as the number of customers wasn’t quite high enough, and the company wasn’t doing well. By the time of this deal, eMachines had roughly a thirteen percent share of all computers sold in the USA, but they also had far lower gross margins than their competitors of about four percent. For comparison, Compaq’s margins at the time were about twenty three percent. eMachine’s was also burning cash with a loss of about $84 million for 1999 (or $156 million in 2024) on revenues of $815 million (or $1.5 billion in 2024).

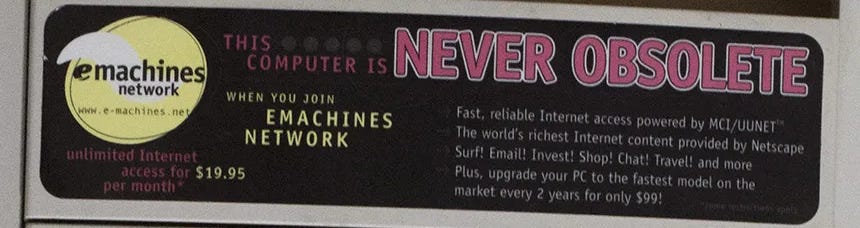

A heavily modified version of Free-PC’s strategy surfaced in the “Never Obsolete PC” strategy that eMachines unveiled shortly after the acquisition. The idea behind this was that the machine could be had for free after rebates. So, a customer could purchase a machine for around $500, get the store’s mail-in rebate, eMachines’ mail-in rebate, and an ISP rebate, and thereby pay nothing for the machine. Of course, the ISP was through MCI/Worldcom via the eMachine’s network for $19.95 per month (about $37.16 in 2024) which offered customer support, email services, and a $99 (roughly $184 in 2024) PC upgrade every two years. This required a minimum two year contract.

On the 24th of March in 2000, eMachines made an initial public offering at $9 per share which raised $180 million (roughly $324 million in 2024). The price fell quickly and by the end of the year the price had fallen to just $0.14. The company was delisted by NASDAQ on the 24th of May in 2001 with price of $0.38 after having traded below $1 for several months. Over second half of 2001, Hui purchased all of the remaining shares for $1.06 per share for a total of $159 million (about $278 million in 2024), and he then hired Wayne Inouye as CEO.

The company continued to increase its sales figures, and then in September of 2003, began to put the hurt on the rest of the market in a big way. Not only was eMachines a low cost manufacturer, but they began to offer seriously powerful systems. eMachines launched the T6000 and with this machine’s release became the first PC manufacturer to offer an AMD64 PC, and they priced it at just $1150 (about $1939 in 2024). The machine shipped with an AMD Athlon 64 3200+ clocked at 2 GHz pulling 89 watts on socket 754, 512MB of RAM, an ATI Radeon 9600 with 128MB of VRAM, a 160 GB HDD at 7200 RPM, one CD-ROM drive, one DVD-ROM drive, and a memory card reader. Early in 2004, the company was the first to release an AMD64 laptop PC with the M6000. These machines helped the company shed its image of offering only computers of low quality, an image it didn’t deserve as (at least according to PC Magazine) eMachines had lower rates of failure than Dell or Gateway, put the company firmly in the black with sales over $1 billion (about $1.6 billion in 2024), and bumped it to number three by market share. Compaq and HP were forced to merge, IBM sold its PC division to Lenovo, and put Gateway in a very precarious position.

At COMDEX in 2002, Hui had spoken with Gateway’s founder and chairman, Ted Waitt, about the possibility of purchasing Gateway and taking it private. The two then continued to discuss the idea off and on, and it almost became a reality in the middle of October as Gateway’s share price was falling. Ultimately, the cost was still too high. Then, in March of 2004, the reverse happened. Gateway acquired eMachines for fifty million shares of Gateway stock, and $50 million cash (about $82 million in 2024). Hui became the largest share holder of Gateway but was given neither a board seat nor an operational role, and Wayne Inouye became the CEO of Gateway. The newly combined company was headquarted in Irvine where eMachines had previously been, they closed the Gateway Country Stores, and they adopted eMachines’ inventory and sales practices (which were largely strategies copied from Dell, and to a lesser extent HP). After the sale, Lap Shun Hui chose to give every single one of his one hundred forty employees a very large bonus. For some, this bonus would represent a figure that was roughly thirty percent of their annual salary. For his executives, they split twelve and a half million shares of stock. Managers who didn’t receive shares, received nearly $100000 (or $164000 in 2024). In 2006, Hui attempted to purchase the company for $450 million (about $693 million in 2024), but the board didn’t accept. Gateway sold to Acer in 2008. The eMachines brand was discontinued in 2013.

I now have readers from many of the companies whose history I cover, and many of you were present for time periods I cover. A few of you are mentioned by name in my articles. All corrections to the record are welcome; feel free to leave a comment.