The Story of Napster

The Beginning of the End of Physical Media

I was sitting on a blue carpeted floor in the living room of my parents’ house with a Bic pen trying to wind the tape back into a cassette after my father’s tape deck in his HiFi system tried to eat it. It was a decent summer day in Cincinnati, and I had little reason to be indoors other than the fact that, for me, music wasn’t yet portable. I couldn’t have been more than seven years old, and that was far too young an age to have something as expensive as a Walkman. I personally only had five tapes at the time, and two of those, I used to record music off of the radio. That was music for young me. My friends and I would sometimes swap our mix tapes to get something a bit fresher for our ears, and none of us had any CDs. My father, mother, and my older siblings had some CDs, and they were amazing. I didn’t yet. CDs weren’t exactly cheap, and an eight year old wasn’t exactly responsible. Finally getting the tape rewound, I put it back into the player, pressed play, and hoped that I’d hear something from the magical band of rust-coated polyester. Alas, I was now down to just four tapes. Disappointed, I powered off the sound system, ran to the garage, and hopped on my bike.

A few years later, I was blessed with two different pieces of technology. The first was a desktop computer that was all mine. The second was a portable minidisc player/recorder. These most definitely weren’t cheap devices, and I treasured them. I could now borrow CDs from friends, rip them, copy the songs to minidiscs, and take my music with me wherever I went! This didn’t just allow me to listen to jazz, classical, punk, ska, metal, or whatever else whenever I wished, it also allowed me the ability to be alone in a crowd. For a nerdy youngster, this was truly a dual blessing.

Of course, even with this major change to daily life, I still had to get the audio in the ways familiar to everyone alive at the time. I could go to a record store and pickup a tape, CD, or vinyl. I could borrow media from a friend and copy it. I could record stuff from the radio. With any of these methods, I could store them on my computer, or I could just record to a blank minidisc similarly to a tape. The problem was, the music selection was limited to what I could physically get my hands on. My entire world of music was limited to roughly twenty albums and whatever four songs were on repeat at the local station. This was largely due to the price of an album. A single CD in the second half of the 1990s would cost between $15 and $20 which today in 2024 would be about $30 to $40; too much for a kid who made money mowing lawns, raking leaves, and shoveling snow. Even just a bit later working part-time at Kroger, CDs remained a rather expensive luxury for me. There was diversity in the genres of music in that collection, but it was really rather easy to tire of nearly all of it. I had no idea at the time, but this situation wasn’t going to last long.

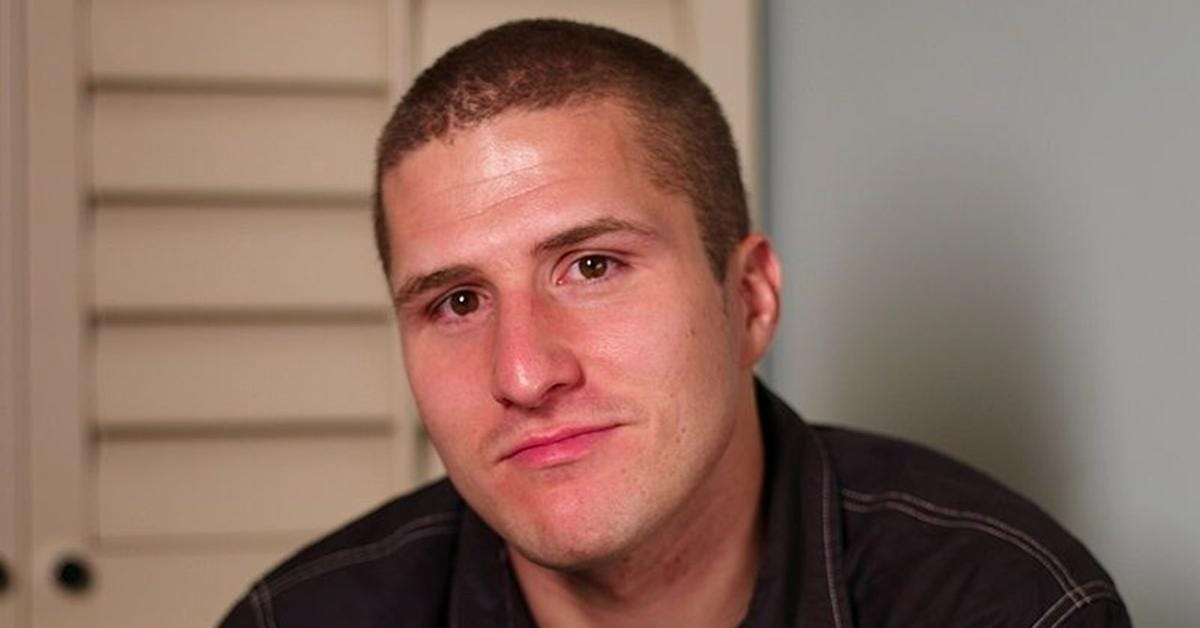

Shawn Fanning was born on the 22nd of November in 1980 in Brockton, Massachusetts. Unusually for this publication, he was far more interested in tennis, basketball, and baseball than he was anything computer related, and he was a talented athlete. At any other time, in any other place, surrounded by any other group of people, it is highly likely that Fanning would have become a professional athlete especially as the windy city of Brockton is the City of Champions. Yet, Fanning did not become a professional athlete. He and his friends had access to computers, to the early internet, and they found themselves gathering in #w00w00 on EFnet where they discussed things like programming, physics, and hacking. Fanning had long been called Nappy due to this hair, and he embraced the name. His handle on IRC was Napster.

Fanning’s uncle, John, ran a company called chess.net and Shawn worked there in the summers. Shawn Fanning graduated from Harwich High School in 1998, and he enrolled at Northeastern University. One night, he was having a beer with his roomate, and his roomate started lamenting the dead links to MP3s that littered the web. The light bulb went off and before long Fanning began discussing an idea to build a file sharing network around a centralized music database. He was later quoted by CNN as having said:

I had this idea that there was a lot of material out there sitting on people's hard drives. I mean, even if you were at Lycos or Scour, you were still looking at people's hard drives. So that's the idea, that there's all this stuff sitting on people's PCs and I had to figure out a way to go and get it

Despite his grand vision, he still needed to work, to go to school, and to make progress toward the milestones expected of a young American.

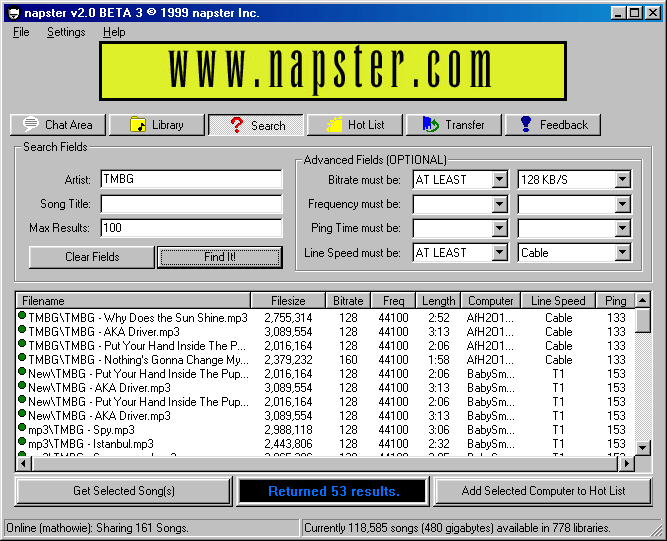

In his spare time, Fanning kept pursuing the idea. First, he had to learn the Win32 API. Second, he had to learn UNIX programming for the server software that would provide the directory. On the floor of his uncle’s office, armed with a Dell laptop, he variously worked for his uncle and worked on his project. In January of 1999, he chose to drop out of college, and he didn’t even go back to the school to fetch his belongings. He moved in with his uncle, and he devoted himself full time to his project. His parents were dismayed, and his friends on IRC doubted that anyone would willingly share their files. Yet, Fanning knew something that few others did. Not only would people be willing share their files, they’d congregate around their favorite genres to discuss the music they loved so much. They’d search for music by artist, or by title, and they’d filter by a file’s bitrate. They’d check the most popular stuff if it was shown, and they’d even help the software’s creator improve things. They’d do all of these things voluntarily, and they’d tell everyone they knew about it.

One of Fanning’s friends from IRC was Sean Parker. While Parker had some background in computing, that wasn’t really his contribution to Napster. Parker, along with Fanning’s uncle, convinced Fanning that Napster might be a business. After getting that settled, Parker went on to raise $50000 to fund Napster’s launch.

On the 1st of June in 1999, Napster was released to the world. Those who doubted that file sharing would be popular were mistaken. The web was young. While the creation of the world wide web had driven the sales of computers, modems, and ISP subscriptions, less than half of the homes in the country had a computer, and fewer had internet access. In 1997, about thirty seven percent of households in the United States had a computer and about eighteen percent had internet access. By the end of the year 2000, around half the country had a computer at home, and about forty two percent had internet access most of which would be dial up access at or below 56kbps. Despite this, by the close of 1999, Napster’s total user count was more than twenty million. Napster was so popular that many universities began banning the program as it was accounting for around two thirds of all network traffic, and causing rather severe problems for all users of the universities’ networks.

Napster was totally new, totally unique, and totally awesome. A new user would download the application, and when launching it for the first time, he/she would be asked to set a username, to set a password, and to provide a storage location for his/her MP3s, where new ones should reside, and what application should play MP3s. Once that was sorted, after login, a user would see a chat window.

Sometime in the year 2000, Parker and Fanning moved to San Mateo. The Napster office was above a bank, and the two shared a rather modest two bedroom apartment with rented furniture. They didn’t have a phone line, and they used their cell phones instead which was quite uncommon at this time as banks and insurers usually required both a home phone number and a physical, non-PO box, address. Fanning’s younger brother, Raymond, was often present and sleeping on their couch and learning software development. Rather typical for young men but out of place for Shawn Fanning, the dining table and coffee table were often piled with empty soda cans, pizza boxes, CDs, and DVDs and the focal point of the living room was a sixty inch television. Previously, Fanning had been one to exclude carbohydrates from his diet and regularly hit the gym in the evenings rather than laze about.

Despite the wonders of Napster, and despite the assuredly very fun life Fanning and Parker were living, flagrantly violating intellectual property rights doesn’t normally sit well with owners. It was one thing when the piracy was uncontrollable, as it was with CDs and tapes, but the ability to replicate digital information infinitely was something completely foreign to the recording industry. Panic. The first bits of litigation began on the 6th of December in 1999 in northern California. In February of 2000, the board of the Recording Industry Association of America, consisting of record label executives, met at the Four Seasons in Los Angeles. Hilary Rosen, then the CEO of the RIAA, had a PC brought in with Napster installed on it, and she asked the bossmen to name some songs (including some that had yet to be released) and she was able to find every single song on Napster. Greater panic. A group of people who’d once thought of MP3s as an amazing opportunity to increase the density of information on any given medium now saw them and the software used to distribute them as an existential threat to their businesses. These men and women had even dreamed of a heavenly or celestial jukebox that would hold every song ever recorded and be able to play them on demand to any user, but shown this exact thing pulled from their daydreams and made manifest, they were horrified.

To make Napster’s position worse, members of Metallica heard an unreleased song of theirs, titled I Disappear, on the radio. The song had been circulating on Napster along with everything the band had ever recorded. Not content to wait for the RIAA’s members to prevail in the courts, the band filed a lawsuit against Napster on the 13th of April in 2000. Metallica’s attorneys then hired NetPD to watch Napster over the course of the weekend of the 29th and 30th of April. The consulting firm collected a list of three hundred thirty five thousand four hundred thirty five users of Napster who’d illegally swapped Metallica’s songs. That list on its six thousand sheets of paper was in thirteen cardboard boxes in a black SUV and being driven to Napster’s San Mateo office. Metallica was requesting that those users be banned from the service. Anticipating the arrival of the band and their attorney, protesters had already gathered, and their rage was palpable. They were smashing Metallica CDs and albums with sledgehammers, and when Lars Ulrich came up to a podium to address the crowd, the crowd addressed him back. He tried to claim that his actions weren’t about harming fans, but rather about Napster, and the crowd then asked why Metallica was targeting fans. Someone else then shouted out a question about whether or not Ulrich had even used Napster. The answer was no, and this was met with mocking laughter. A reporter then asked if Ulrich could provide a quantification of any losses incurred by piracy on Napster, and Ulrich stated that this wasn’t a matter of revenues. It was a bad press day for Metallica. Within a week of Metallica’s case being started, Dr. Dre also filed a lawsuit with the help of the same lawfirm. Dr. Dre likewise delivered a list of usernames to Napster.

On the 2nd of October in 2000, A&M Records along with eighteen other record companies, all of whom were members of the RIAA, made their arguments against Napster before the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. As a result of this case, Napster was required to show to the District Court in a separate trial that it could keep track of user activity on its service and prevent the distribution of copyrighted work. Napster clearly could not comply with this, and the company ceased operation on the 11th of July in 2001. It then settled its various legal cases paying out nearly $40 million. All of this legal action, and all of Napster’s losses, were taking place while album sales were hitting all-time highs. If anything, it would seem, Napster was helping the music industry more than it was harming it.

Napster now needed some money. Of course, it’s quite difficult for a company to make money when offering a product for free. The first move Napster made was to charge users $5 per month and use this to pay licence fees to the record companies. This then saw the company create the .nap file format which added DRM to the files in users’ libraries. This had the side benefit of allowing tracking of files shared ensuring that those who paid got the files, and that relevant companies got their cut. The company also signed a deal with MusicNet and Real Networks allow people to stream and/or purchase music directly rather than sharing music. On the 17th of May in 2002, Bertelsmann AG announced its intent to purchase Napster’s assets. Konrad Hilbers became the CEO and Fanning became the CTO. The company declared bankruptcy on the 3rd of June in 2002, which was planned with the hope that Bertelsmann would be buying a company that was free of debt obligations. Bertelsmann then provided some funding to allow Napster to make it a bit further. Version 3 of Napster saw a limited alpha release, and the company blocked old versions of Napster from their service. This didn’t really work out well. The user count plummeted, the number of downloads plummeted, and Napster was dying.

On the 3rd of September in 2002, the Bertelsmann acquisition of Napster was blocked with the judge stating that the deal was not negotiated in good faith. Napster then laid off its employees, ceased all operations again, and began the process of liquidating its assets. At auction, the brand and the logos of Napster were purchased by Roxio who then used these for a a media store and streaming service. This lasted until 2008 when BestBuy purchased Napster. This was a sort of value add for their own Insignia line of MP3 players. You could buy your device at BestBuy and sign up for BestBuy’s subscription service or buy your songs and albums individually.

In 2011, Rhapsody was failing. The company had struggled against iTunes, and it was now struggling against Spotify. Rhapsody then chose to purchase Napster from BestBuy and make it purely a streaming service. Ultimately, Rhapsody failed as well. Napster was sold to MelodyVR on the 25th of August in 2020, and then to Hivemind and Algorand on the 10th of May in 2022 which formed Napster Music Limited. On the 9th of March in 2023, Napster Music Limited entered liquidation, a state that continues at the time of this writing.

Napster’s brief life completely changed the music industry. MP3s and MP3 players became popular, and in the wake of Napster’s exit, iTunes arose. As iTunes and the iPod largely replaced CDs and CD burners, streaming started to rise. Today, while CDs and vinyl still exist, these are the domain of enthusiasts. Most people now simply stream their audio from Apple Music, Spotify, or Amazon Music. As these changes were occurring, physical media was largely ended in the world of video, software, news, and magazines as well. Once people had become accustomed to paying for things without receiving a physical artefact, the cost savings pushed other markets to do the same as much as was possible. It is hard to describe just how exciting Napster really was. It was a magical gateway to music of any and every genre, to every song ever made, and to that sense of a boundless frontier ready for exploration. Today, that feeling is missing as the celestial jukebox has become something quotidian. As a normal part of every day life, it has just become another background element despite being an amazing technological marvel.

I have readers from many of the companies whose history I cover, and many of you were present for time periods I cover. A few of you are mentioned by name in my articles. All corrections to the record are welcome; feel free to leave a comment.