The Tandy Corporation, Part 1

From leather shoe bits to the TRS-80

In 1919, a small leather company was founded in Fort Worth by David Lewis Tandy and Norton Hinckley. The Hinckley-Tandy Leather Company specialized in leather show laces, shoe soles, leather and rubber heels, and other shoe-findings. Tandy focused on sales and marketing while Hinckley managed the internal business operations and inventory. The company did well, bought a larger location in 1923 and expanded to Beaumont in 1927. The company scaled back during the Depression, but they survived.

Charles David Tandy, the son of David Lewis Tandy, was born a year before Hinckley-Tandy started operations, and he began working at the company at the age of twelve. He graduated from Texas Christian University in 1940, briefly attended the Harvard Business School, and he then joined the US Navy. The younger Tandy served as a supply officer, but he also setup a leather working program for hospitalized personnel. This was successful, and it provided the inspiration for his first major contribution to Hinckley-Tandy after his discharge in 1948: Tandy Leather, a mail order hobby division of the company.

Disagreements between Hinckley and the Tandys were growing. Hinckley wanted to focus on the shoe-findings that had built the company, while the Tandys had greater ambitions. The Tandy family ended up in control of the company and the hobby division had achieved 100% ROI in its first year. In May of 1950, Charles Tandy opened the first two retail locations specialized in leather craft, but the company’s main revenues came from their mail order business. At two years, the company had achieved $2.9 million in sales, opened 15 stores, and wasn’t yet ready to stop its expansion. By 1952, the company had stores across the country, had acquired a few failing competitors, and had established an interesting method of encouraging both employees and store managers to succeed. Each store was incorporated individually, and store managers were required to own a 25% stake in the store. Should a manager lack the capital personally, Tandy Leather was available to provide the loan for that purpose, and Dave Tandy would serve as a co-signer should it be needed. For regular employees across the company, year end bonuses were provided, and all staff were eligible and encouraged to purchase equity. This worked well; by 1954, the company’s catalog was 68 pages and served a million customers, four factories stocked the shelves of 67 stores spread across 36 states and the territory of Hawaii.

While one might assume that taxation would require respiration, this is not so. In 1954, Dave Tandy passed away and the estate taxes hurt the company’s finances rather badly. This sudden shift in the company’s fortunes also meant that employee stock holders had no meaningful way to assess the value of their shares. As the remaining Tandy in our story saw it, the easiest way to ameliorate the concerns of share holders was for the company to go public. Given the company’s size, this would have been difficult, and he therefore sought a merger with an already publicly listed company.

The merger target Tandy found was the American Hide and Leather Company. AHLC was insolvent and this presented Tandy with the chance to remain in control of the resulting conglomerate. Tandy Leather provided AHLC the money to buy Tandy Leather, and Tandy Leather share holders had the option to buy shares in AHLC. This merger was completed in 1955, the company was renamed to General American Industries Inc, Tandy became the president, and the combined entity had a five year tax shelter due to AHLC’s insolvency. With AHLC as the corporate parent, profits from Tandy Leather were being used to cover the losses of other conglomerate members such as Western Leather and Tex Tan. To stop this would mean that Tandy would need to regain control. This was achieved in November of 1959.

With Tandy now in control, the unprofitable child companies were sold at a loss, the company’s headquarters was moved to Fort Worth, the conglomerate was renamed the Tandy Corporation, and the stock symbol became TAN. At open the stock was $4/share, and by the end of 1961 it was $11/share.

With ownership, earnings, taxes, and other issues settled, Tandy changed his focus back to growth. The first two initiatives were experimental retail stores Tandy Craft and Hobby Mart in November of 1961. The first stores were around 18,000 square feet, sold more than 50,000 items of varying kinds for a variety of hobbies, and notably included Electronic Crafts like DIY radio and stereo kits. Other diversification efforts continued over the decade with names like The Mart, and Pier 1 Imports.

Two years after the founding of Hinckley-Tandy, on the other side of the country, brothers Theodore and Milton Deutschmann founded Radio Shack in Boston. The company’s aim was to serve the growing amateur radio market, and their first offerings were surplus military equipment. Ironically, these were two London born men operating a block away from the Boston Massacre, but history is always funny that way. The first “retail” location was actually a basement at 46 Brattle Street. So, we have two brothers with a modest square footage in a basement on what was decidedly not a major thoroughfare. Still, the rent was rather cheap at just $50/month (a bit shy of $900/mo in 2025), and the company was originally a sole-proprietorship so there weren’t investors or corporate boards to worry about. That ownership structure changed on the 26th of December in 1935 when the company became the Radio Shack Corporation. On the 1st of October in 1938, the company moved to 167 Washington Street, and they chose to start a mail order catalog in 1939. In 1954, Radio Shack began selling private label products under the name Realist, but the name was changed to Realistic after some litigation. In 1959, the company moved their headquarters to 730 Commonwealth Avenue. By the 1960s, the company had nine retail stores, the catalog, and the company was a leader in their market. Despite their seeming success, the Radio Shack wasn’t the best run, and an experiment with customer credit offerings turned out to be a bad move. By 1963, the company was moribund with nearly $800,000 of credit extended to customers that was uncollectible.

As we’ve already seen, Tandy had recently expanded his companies into the hobby electronics market, and he was something of an expert in retail operations. In 1963, Tandy acquired Radio Shack for $300,000 (around $3.1 million in 2025) and formed Tandy Radio Shack Corporation more commonly recognized as TRS. Nearly all of Tandy’s attention switched from the leather companies to Radio Shack. The goal of Radio Shack was largely unchanged under Tandy’s ownership with that being to serve hobbyists, children, and those wishing to save some money buying cheaper stuff and modifying and accessorizing as they saw fit. What did change was inventory. First, Tandy cut 17,500 items, and those that remained were the company’s best sellers. Second, those items that remained were mostly private label which eliminated middle-man markups. These private label products were created with exclusive contracts directly with manufacturers. Over time, this would change to products designed and manufactured by the Tandy Corporation. The keys to Radio Shack’s survival were then high profit margin, high inventory turnover, in-house marketing, in-house distribution, and consistently stocking only what the market wanted. As for marketing, roughly 9% of profit went into advertising in the years immediately following the acquisition.

Just as with Tandy’s other stores, he encouraged retail store managers to be shareholders. It wasn’t unusual for store managers, VPs, and Tandy himself to earn roughly ten times their salaries through profit sharing bonuses and stock. Over its years of operation, Radio Shack created around 60 millionaires.

On the 9th of August in 1973, the first Radio Shack outside the USA was opened in Aartselaar, Belgium. This store was different not only for being outside the USA but also for not being called Radio Shack. As all non-US stores after it, this location was just Tandy. The first Tandy store in the UK was opened on the 11th of October in 1973 in Birmingham.

In 1975, the Tandy Corporation split into three companies: The Tandy Corporation, Tandycrafts, and Tandy Brands. The Tandy Corporation held Radio Shack and the Tandy electronics stores. Tandycrafts held Tandy Leather Company, American Handicrafts, Decorating and Crafts magazine, Color Tile, Magee, Merribee Needlearts, Woodie Taylor Vending, Automated Custom Food Services, Stafford-Lowdon, and Bona Allen. Finally, Tandy Brands was the clothing and accessories company.

The success of the Altair 8800 caught the attention of Don French who was in charge of Radio Shack’s electronics hobby kit lines. French was a microcomputer enthusiast and had built himself a Mark-8. Upon release of the Altair 8800, he bought one of those too. With an Altair 8800, French was able to write some inventory software and automate gross-margin reports helping Radio Shack determine which products should be kept and which should be discontinued. French and John Vinson Roach II (data processing manager) were both in Silicon Valley in 1976, and French, as a computer enthusiast, invited Roach to join him in attending the West Coast Computer Faire. Apparently, this made an impact on Roach as, upon returning to the office, he wrote a quick note to Tandy stating that there was a market in microcomputers. Roach then chose to attend a presentation on calculator chips at National Semiconductor on his next trip to the valley. One of the people speaking there was Steve Leininger. The two met up after the presentation, and Roach then had French interview Leininger for a job. The interview went well, and Leininger was hired.

For his part, Leininger wanted Radio Shack to offer a computer kit. French however, knew this wasn’t a good idea. Among the many customer support requests that French’s division saw, the largest plurality was due to poorly understood and/or poorly executed solder jobs. The two then began preparing a pre-built microcomputer. They chose the Zilog Z-80 as their CPU partly due to cost and partly due to French already having an Altair with an Intel 8080. Their prototype was assembled on a table with a gutted RCA television serving as a monitor. The keyboard sat in front of the TV, and the rest of the wire-wrapped system was under the table. The prototype booted to a modified version Li-Chen Wang’s public domain Tiny BASIC that Leininger had put together for their purposes, and French wrote a simple tax program for demonstration. Tiny BASIC took 2K RAM, and this left just another 2K for applications in their 4K RAM and 4K ROM system.

In late 1976, the computer was ready for demonstration. Tandy arrived and sat down at the table where the tax program (named H&R Shack) was waiting. French instructed him to enter his salary, and Tandy did. The program crashed. The largest number that the program could handle was 32,767 and French then told Tandy to lower his entry. A quick reset, a far lower salary, and the program worked. This demonstration earned Leininger and French a meeting with the Radio Shack executive team, and one of the first questions was asked by Tandy: “How many can you sell?” French and Leininger responded almost concurrently with 50,000. This brought laughter out of everyone, even Roach.

Having had to work in secrecy, then experiencing raillery, I cannot imagine that these two men felt very good. Yet, they’d won, and Tandy agreed to fund the manufacture of 1000 units. He didn’t necessarily believe in the product, had little interest in computers, but Tandy knew that Radio Shack needed innovation, needed new products, and needed to take a little risk. The project was formally approved on the 2nd of February in 1977 and the production run was increased to 3500. You’d think that moving from 1000 to 3500 computers was evidence of growing support for the project, but no. This 3500 number was so that when the computer failed to sell, Tandy Corporation could use them in their Radio Shack stores for inventory control — stores which numbered 3400 at the time.

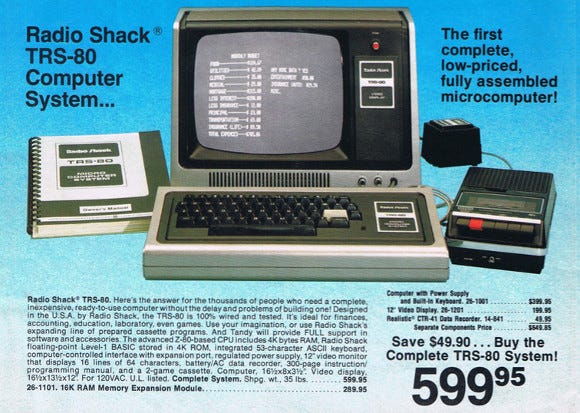

French and Leininger had the green light to build a computer, and they did so. The computer they designed was the TRS-80 (later retro-actively called the TRS-80 Model I). The computer featured a Z-80 at 1.77MHz, 4K RAM, 4K ROM with Level I BASIC (a slightly more refined version of that earlier Tiny BASIC), a monochrome display with uppercase-only text of up to 64 columns by 16 rows, 128 by 48 low-res graphics, cassette storage of 250 baud, and a 53-key keyboard into the housing of which the system board was fitted. With the RCA monitor and Realistic cassette drive, the TRS-80 sold at $599.95 and was the single most expensive product Radio Shack had ever carried. For just the computer itself, the price was $399. At this point in history, a computer would require a manual, and for this they called upon the services of Dr. David Lien who’d been one of French’s professors. Lien would go on to author many books and manuals in the microcomputer world.

The TRS-80 was announced at a press conference at the Warwick Hotel in Manhattan on the 3rd of August in 1977. Sadly, terrorist actions disrupted the city that day. The Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional Puertorriqueña wanted independence for Puerto Rico from the USA, and toward this goal a bomb was detonated in the offices of the Department of Defense at 09:37. Thankfully, the bomb had been discovered, people had been evacuated, and no injuries resulted. An hour later, another bomb detonated in the offices of Mobil Oil, and this second attack resulted in the death of one with another seven injured. As news companies spread warnings about further bombs, some 100,000 workers evacuated offices around the city.

The following week, Don French took all three existing computers to the Boston Computer Show. Tandy’s booth was quite busy, and the three TV networks all wanted access too. This should have been an indicator that the company had something worthwhile, and... French got back to the office to find that he couldn’t place any calls. The company phone system was getting constant calls from people wanting to buy a TRS-80, but Tandy hadn’t actually made any just yet; they were still planning to use them for inventory control when the product failed. There were also precisely two people at the company well versed in computers, and of French and Leininger, it was French who was the more social. So, French it was who had to talk to all of these excited people. When the company finally had quantities of computers to ship in March of 1978, all of them sold. Within the first month of availability, 55,000 sold, and by 6 months the computer accounted for about 40% of Radio Shack’s business. In the first 12 months, 100,000 TRS-80s were sold. Radio Shack held almost two thirds of the microcomputer market.

Along side the TRS-80, Radio Shack offered five software programs. There was the Game Package for $4.95, Payroll Program for $19.95, Education - Math 1 for $19.95, Kitchen for $4.95, and Personal Finance for $14.95. This software library quickly expanded with both first party and third party software titles, and ultimately nearly 16,000 titles would be released.

Leininger and French weren’t really satisfied with Level I BASIC, and as a result they contacted Bill Gates for a port of Microsoft BASIC. After quite a bit of negotiation, Gates was convinced to do this for a flat fee, quite a rare thing. Of course, while this became Level II BASIC for the TRS-80, Gates would sell this version of BASIC to many other companies using the Z-80. There was just one issue: Level II BASIC required 16K RAM. As a result, the Level II Model I was born. For those who already owned a TRS-80 with Level I BASIC, an upgrade kit was made available for $120. After a bit of time, the Level I with 4K was $499 (about $2455 in 2025), the Level I with 16K was $729, the Level II with 4K was $619, and the Level II with 16K was $849 (around $4177 in 2025).

From the start French had wanted the computer to be expandable. To this end, Radio Shack released the Model I Expansion Interface. This was a proprietary box that included a floppy disk controller, Centronics port, a second cassette connector, and a card edge that could be used with a hard disk drive, voice synthesizer, or other peripheral. The EI had optional RAM (either 16K or 32K) and RS-232. This expansion is one area where cost cutting caused some issues. The six inch ribbon cable that connected the EI to the TRS-80 wasn’t shielded and it was rather close to the largely unshielded RF modulator, the card edge was made of base metal and would frequently oxidize, it had no power indicator, the power button itself was recessed and hard to press, and when powering on or off a transient electrical surge from the floppy drive head could create a magnetic pulse that would corrupt data. Had a user not read the manual, the initial power on with the EI could cause some confusion. Without any disk in drive 0, the machine would display a full screen of random garbage. A user would either need a disk inserted to boot from, or he/she could press BREAK+RESET and drop to BASIC. All together, these issues earned the TRS-80 the nickname “Trash-80.”

Up to four SA-400 floppy disk drives could be daisy-chained to the EI which is good because 5.25 inch floppy disks had a formatted capacity of just 85K at the time. Along with the drives, in July of 1978, Radio Shack released TRSDOS written by Randy Cook. The initial versions of TRSDOS provided the necessary extensions to BASIC to handle I/O commands for disks and files rather than tapes.

With the immense interest in the TRS-80, Radio Shack began building Tandy Computer Centers, the first of which was at the bottom of Tandy Center. Tandy Center itself was quite something. The development housed an ice skating rink, a private subway system, and a retail shopping mall. That shopping mall would now include a Tandy Computer Center.

On an undisclosed Saturday sometime in mid-1978, Don French went to the top floor of Tandy Center with no appointment. He walked into the office of Charles Tandy and he said: “you know I saved Radio Shack.” The response was: “you’re full of shit.” The two proceeded to discuss the matter. French made the solid point that CB radios had fallen, computers had risen, and the continued success of the business was dependent upon this new division for which only Leininger and French had fought. The result of this impromptu meeting was that French was promised a VP title, pay to match, and a large bonus in compensation for his past efforts.

Charles Tandy passed away in his sleep on the 4th of November in 1978. He saved and then built Tandy Corporation into a massive multinational corporation with more than 20,000 employees, 7000 Radio Shack stores, a beautiful 8-block headquarters, and helped to bring electronics to the masses. While doing all of that, he also served as a director for the Fort Worth National Bank and was a founder of the North Texas Commission.

Phillip North served as the company’s interim president and CEO, and he did not honor Tandy’s deal with French. Immediately following that news, French went and cleaned out his office. He then went into business on his own, releasing a version of CP/M and an S100 bus adapter for the TRS-80, and again working with Bill Gates on porting Microsoft’s software to CP/M on the TRS-80.

Leininger and French had been mocked, but the TRS-80 turned Radio Shack into a microcomputer company.

I now have readers from many of the companies whose history I cover, and many of you were present for time periods I cover. A few of you are mentioned by name in my articles. All corrections to the record are welcome; feel free to leave a comment.