Compaq Computer Corporation, Part I

AUDENTES FORTUNA IUVAT

In late September of 1981, Rod Canion, Jim Harris, and Bill Murto were working at Texas Instruments, and they weren’t exactly pleased with that. They’d had some discussions about leaving TI to create their own company, and they’d decided that their goal was to make a Winchester disk controller add-in card for the IBM PC. Canion went to visit his local public library where he checked out a few books on making business plans. The group read the books and set about writing the plan, each working on separate sections after creating an outline together. None of them knew the precise number of product they’d make, how much of that volume they’d sell, and therefore they had no clue what revenues they’d have; Canion just guessed.

An industry consultant, Portia Isaacson, visited the men in Houston in October of 1981. Canion drove Isaacson back to the airport and the two discussed venture financing on the way. Isaacson mentioned that Leonce John Sevin Junior (L. J.) had started a new venture capital firm. Canion sent Sevin a copy of the business plan which Sevin shared with his partner, Benjamin M. Rosen. They replied that they’d consider it, and then crickets. Despite having been turned down by Sevin Rosen Funds, Ven Rock, and Kleiner Perkins, Harris and Canion resigned from TI on the 14th of December anyway. Murto chose to remain with TI for a while as he and his wife had a newborn daughter. Not being employed by TI, Harris and Canion researched more product ideas. Previously, they’d restricted themselves as they didn’t want to compete with their employer. The new company became real on the 14th of December as they registered a DBA of Gateway Technology at the Harris County Courthouse. They then opened a bank account with $1000 from Harris and another $1000 from Canion (that $2000 would be about $6500 in 2024).

For Harris and Canion, things were a bit precarious. They’d each saved about six months of living expenses prior to leaving TI, but they didn’t have a product. They met daily to work on their new company. Then came the morning of the 8th of January. Canion was drinking some coffee and an idea occurred to him. What if there were a portable computer that could run software written for the IBM PC? He knew it would need to be a rugged machine and that this would complicate making it light enough to be portable, and he immediately figured that if no one had done this then there must be a flaw with the idea. Despite that nagging feeling, Canion kept right on pursuing it.

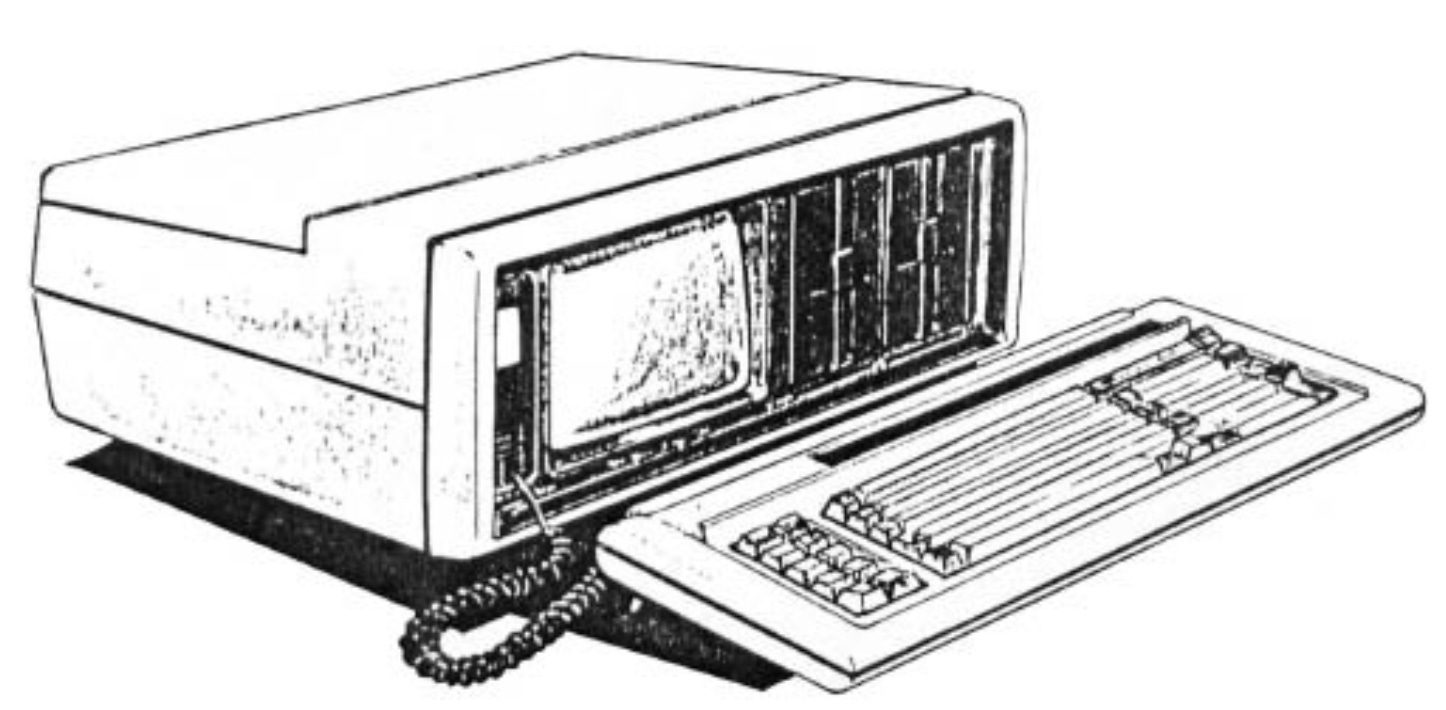

Harris and Canion asked Sevin and Rosen to meet with them on the 20th of January in 1982. The aim was to convince the other two to invest in this new idea. Canion wrote up the description and immediately realized that words alone wouldn’t be sufficient. The primary fear that he and Harris had was that their product would be compared to the Osborne 1, a machine about which both held a rather poor opinion. The meeting was just two days away and Harris hired Ted Papajohn, an industrial designer who’d recently retired from TI, to workup a sketch of the machine that he and Canion envisioned. The three met at House of Pies. They sat toward the back in an attempt to avoid being overheard, borrowed a pencil from the waitress, and as Harris and Canion described the machine, Papajohn sketched the product on the back of a paper placemat.

On the way to the meeting with Sevin and Rosen two days later, Harris picked up the completed drawing from Papajohn and then drove to Kwik Kopy to have color copies made. Harris then met Canion at the hotel where the meeting was to be held, and the two had a working lunch to prepare for the meeting.

At 14:00 on the 20th as scheduled, a taxi arrived at the Hilton and Sevin and Rosen climbed out. Harris and Canion were there to greet them and led them to a room on the first floor. Canion supplied both men copies of their business plan, and he then began describing the product idea. By the end neither of the two investors showed any reaction in any direction, and Canion nervously asked them their opinions. At this point, the two men expressed that they had previously thought of precisely this sort of product, but they expressed doubt that two guys who’d originally come to them with plans for a disk controller could handle a product of this scope. Harris and Canion looked at each other and smiled. They then explained that they’d been working on sturdy aluminum housings, molded plastics, and microprocessor systems for many years, and that they felt rather confident in their abilities to complete the hardware system. Where they did themselves see a bit of a problem was with the ROM BIOS which would need to be reverse engineered without violating IBM’s copyrights. Likewise, they’d need to license both MS-DOS and BASIC, and it wasn’t really a certainty that they’d be able to do so. Sevin provided the name and contact information for a lawyer who’d advise them on the BIOS work, but Gateway Technology didn’t get a commitment from Sevin Rosen Funds. Once again, Sevin and Rosen had said they’d consider it.

Harris and Canion felt energized, and they retreated to Harris’s home to discuss what they’d do next. Swelling its heft from four pages to fifteen, they filled in their business plan with more detail regarding manufacturing, marketing, distribution, and cost estimates. Not wanting to lean too heavily on Sevin and Rosen, they chose to arrange a meeting with Lovett, Mitchell and Webb (another investment firm in Houston).

Our two protagonists met with Jim Callier of LM&W on Monday the 1st of February in 1982. That meeting was at 09:00 in Callier’s office. The two men made their presentation, and they were met with a familiar response. Apparently, LM&W would be in touch. The very next day, Sevin told them that he wanted them to meet with Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers. With no solid commitments but yet another meeting to prepare for, the duo chose to add more meat to their business plan, and Canion prepared a slide deck.

On the morning of the 8th of February, Harris and Canion met with John Doerr. While they were prepared to do a more formal presentation, Doerr was more in the mood to conduct a friendly interrogation of sorts. He asked question after question regarding product differentiation, competition, and a few more things that would have been answered by the slides had the more formal presentation been able to proceed. This went on for a bit less than three hours, but it was successful. Doerr liked the plan, but he needed to confer with his business partners before proceeding.

The next day, Murto left Texas Instruments and came to work at Gateway Technology full time. After being filled in by Harris and Canion on all recent developments, Murto went to work on the marketing plan.

On Wednesday, I imagine that these three men felt like they had had their prayers answered. They were notified over the phone by Sevin and Rosen that they’d have an initial funding round of $1.5 million which would be nearly $5 million in 2024. Of that, $750000 came from Sevin and Rosen, $500000 from Kleiner Perkins, and $250000 from L. F. Rothschild, Unterberg, Towbin. This arrangement required the investors to own fifty five percent of the company. The three founders would then own just twenty five percent, and some other employees would make up the remaining twenty percent. One other condition was that Sevin meet Murto to make certain that Sevin and Rosen would be comfortable trusting the marketing work to him. This didn’t really go well, but Canion stood his ground on his choice and Sevin finally relented. The initial makeup of the company’s board was Sevin, Rosen, Doerr, and Canion with meetings being held at least monthly. Canion was CEO, Harris was VP of engineering, and Murto was VP of marketing. Gateway Technology Inc was incorporated on the 16th of February in 1982. Over the next few days, the startup was little more than three men, a rented office in the Allied Cypress Bank building on Jones Road in Houston, some folding chairs, a table, a single shared phone and line, and some money.

The first real task was then to hire engineers Steve Ulrich, Ken Roberts, and Gary Stimac. The now six person team then realized that were they to clone an IBM PC they would then need an IBM PC. Stimac went and bought one. Four more people were hired over the next three weeks: Steve Flannigan, John Reilly, Walt Russell, and Bill Bray. Flannigan and Stimac then began working with an attorney to create a plan for working on the ROM BIOS. The first rule was that anyone who’d looked at the IBM code published in the manual had to be excluded from working on the reverse engineering project. As Stimac had read the code when flipping through the manuals shortly after purchasing the company’s first PC, it was Flannigan who’d work on writing the BIOS code. Stimac wrote the spec. From there, development continued in a process they called black boxing. Developers, eventually numbering fifteen, working on the BIOS treated it as a black box. They’d feed every possible input in to the BIOS and they’d record the output. They would then write routines that would replicate that functionality precisely.

The next major hurdle was that the earliest MS-DOS versions weren’t truly fully PC-DOS compatible, and BASIC wasn’t either. No one had ever made a fully IBM PC compatible computer (at least not completely legally), and as a result, MS-DOS wasn’t fully and completely compatible. It wasn’t really expected to be. This changed with Gateway Technology. This issue of compatibility was paramount for Canion. In his mind, there was no way for a new entrant to the market to attract enough independent software companies to make a new computer a success. He deeply believed that his product would need to achieve true one hundred percent compatibility. He’d then need precisely zero software companies to target his machine specifically, and every customer would still be assured of having a massive software library available to him/her. He and Murto reached out to Ben Rosen who then arranged a meeting with Bill Gates. Canion brought a copy of the business plan with him, provided it to Gates, explained his product and thoughts, and then asked if Gates could provide a fully compatible copy of DOS. Gates was clearly interested in the idea, but he expressed some serious concerns about losing trust with IBM. A few weeks later, Microsoft delivered something close to what Canion had asked for in May of 1982, but it was not precisely what had been requested. It was simply the closest version of MS-DOS to PC-DOS that Microsoft had available that also wouldn’t violate their agreements with IBM. Gateway Technology Inc would need to find and resolve every incompatibility on their own. So, the company hired more people for various positions, and two of those were software developers. Interestingly, as the company made improvements to MS-DOS and fixed compatibility issues between MS-DOS and PC-DOS, Microsoft became more willing to help. The two companies essentially began a bit of a partnership.

The company’s first prototype machine was working at around 02:00 on the 7th of June in 1982, just a few hours before it was shown to a few members of the press at the National Computer Conference. Neither all of the software nor the BIOS were fully complete but the machine did work.

All of this rapid development in hardware and software was burning cash. By September, the new enterprise was nearly broke. Like a bit of Hollywood, the funding came through right around the time the balance hit zero. The second round was $8.5 million (around $27.5 million in 2024).

Everyone involved in running the company had agreed that a name change was needed before the product officially launched, but this was difficult. No one could really think of anything that seemed to suit them and was also not already taken. Murto then hired Name Lab in California. One of the names they provided wasn’t terrible but it also wasn’t really hitting right. Compaq. Yet, as time went on, it grew on them. They had a name, the Compaq Computer Corporation. In their usage of the word, Compaq means COMPAtibility and Quality.

The company’s production lines were getting started in October thanks to John Walker, Bud Ronemous, Joe White, and some folks from Datapoint. The machine’s software was complete by November, relationships with retailers were building, marketing was on track, and all just from February to October. Then, there was this launch event on the 4th of November in 1982:

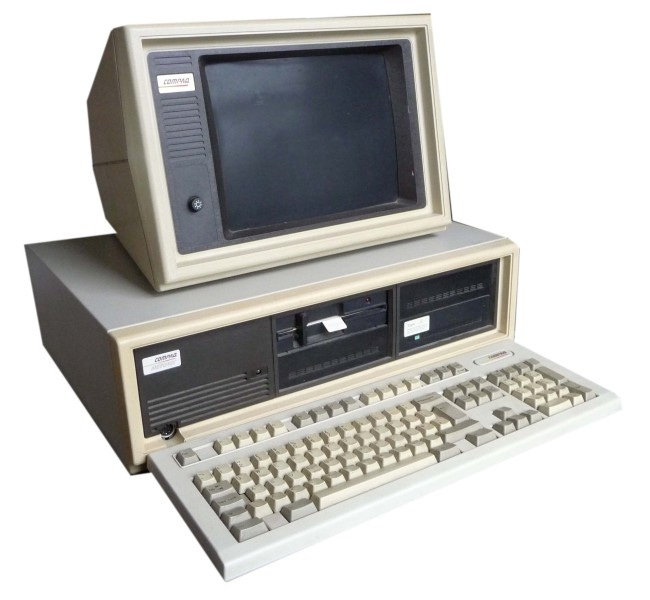

The Compaq Portable shipped with an Intel 8088 clocked at 4.77 MHz, 128K RAM, either two 5.25 inch floppy disk drives, or one floppy disk drive and one 10MB hard disk drive (in the plus model released in 1983), or just a single floppy disk drive. It featured a nine inch green phosphor CRT and a CGA card which allowed for sixteen shades of green on the CRT. RAM was expandable to 640K, and the machine allowed for expansion with three standard eight bit ISA cards. The machine weighed in at twenty eight pounds, and measured 20 by 8.5 by 15.3 inches. Pricing started at $2995 or roughly $9751 in 2024 dollars, and shipments began in March of 1983.

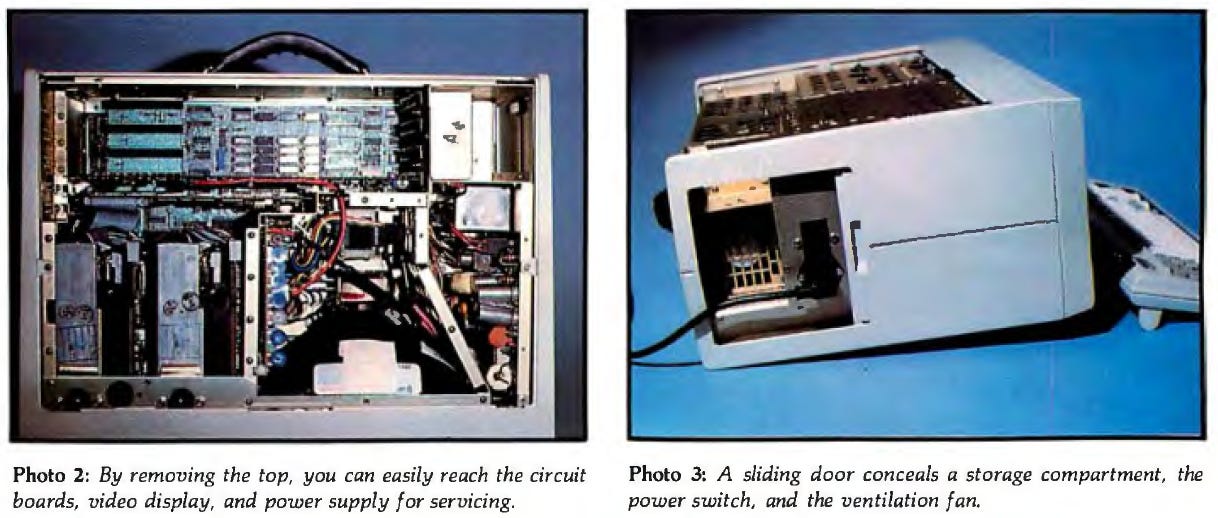

Despite being a portable, this machine was easily serviced. There were access panels on three sides. Importantly, the top panel, once removed, allowed nearly complete access to the system’s internals.

In a departure from the IBM PC’s absolutely amazing keyboards, the Compaq keyboard wasn’t mechanical; it used foam circles with a thin metal film. While this aided in the machine’s ruggedness and portability, it did diminish the overall typing experience on the Portable. It also means that today, all of these machines that remain will need to be disassembled and have those foam pads replaced. To replicate the noise of the IBM’s keyboard, however, Compaq reproduced the click in software with the sound’s volume being adjustable via ALT and + or -. Additionally, the Compaq’s floppy disk drives were quieter than those used in the IBM PC. IBM used drives from Tandon, and Compaq used drives from Control Data. While the noise reduction is nice, the most likely reason for Compaq to choose the CDC drives was that when powered down the drives parked the read/write heads. These drives and Compaq’s software did allow full compatibility with IBM disks, but Compaq users could optionally format disks for 720K. Disks so formatted, however, would not then be readable by an IBM. The Compaq also doesn’t have a cassette tape port or ROM BASIC. Advanced Disk BASIC is offered on the Compaq instead. For most buyers, however, the Compaq Portable gave them an IBM PC with a 320K floppy disk drive, monochrome and color graphics adapters, a parallel printer port, a monochrome monitor, and 128K RAM for $2995 while an IBM so equipped would run $3735 and would lack portability. To make the contrast a bit more intense, the Compaq still has three free expansion slots, and that IBM would be down to one. From Mark Dahmke in The Compaq Computer from BYTE magazine’s January 1983 issue:

The Compaq computer has everything going for it—design, compatibility, portability, and price. The only possible obstacle Compaq faces is IBM itself. IBM has a longstanding reputation for deliberately designing hardware and software that render plug-compatible products incompatible. Barring that occurrence, Compaq should do well by introducing a comparatively low-cost and portable alternative to the IBM PC.

At Comdex in 1982, the Compaq Portable won Best in Show, and it was likewise positively received by every corporate press company whose articles about the machine I could find. The Compaq truly did stand apart from the rest with an Infoworld article by Scott Mace on the 16th of January in 1984, IBM PC clone makers shun total compatibility, citing that only Compaq and Columbia Data Products had made truly compatible machines, and Compaq outsold Columbia by a healthy margin (so much that CDP would file for Chapter 11 in May of 1985). With an incredibly strong product launch behind them, Compaq went public in 1983 raising $67 million. Compaq’s 1983 sales totaled $111 million, which would be roughly $361 million in 2024.

At the start of 1984, Compaq was producing ten thousand computers per month despite parts shortages soft demand. The issue that they faced was that should they lower their order sizes, they might lose priority at a time when getting components wasn’t a guarantee. Compaq also knew that IBM’s Portable Personal Computer would be launched in February. The assumption that the tech press were making at the time was that Compaq would be crushed under the mighty foot of Big Blue. I imagine that despite the confidence Compaq may have had, this caused them fear as well. Still, the executive team felt that demand would recover, that their product would continue to be a success, and that they’d prevail against their business rivals. They continued to build machines and just hold them. They didn’t have a ton of warehouse space, so they started storing the machines in semi-trailers, twenty of them, parked at various locations in Houston.

IBM launched their portable on the second anniversary of the founding of Compaq and at roughly the same time that Rod Canion was performing the ceremonial first shovel groundbreaking at a new facility. Coincidence? Despite the symbolism of a confluence of events, the IBM Portable Personal Computer 5155 was not a Compaq killer. IBM had taken the motherboard of an IBM XT and put it into a case that was similar to the Compaq’s. It was $700 more expensive, had a slightly poorer screen, was heavier, and offered just one advantage; it had more expansion slots. That advantage, however, was made somewhat moot by not having sufficient internal space to fit cards in all of those slots. The 5155 also didn’t quite match the ruggedness and durability of the Compaq. IBM was a bit arrogant, they either didn’t or couldn’t produce enough of the 5155s, and retailers once again began placing orders for Compaq machines. The gamble of producing more machines than had been necessary at the time paid off for Compaq, and they were soon fighting to get enough machines built to fulfill orders. Compaq outsold the IBM 5155 by about five times in that first year, and about seven times the following year. In early 1986, IBM withdrew their portable from the market.

How did Compaq keep the loyalty of retailers in the face of IBM’s entrance into their market? Well, the company had recruited H. L. Sparks to build the dealers network, and this was something that Sparks had already done at IBM. He knew the most important players in that arena personally, had good relationships with them, and knew exactly what would entice them to keep giving Compaq shelf space. With Compaq, computer retailers had control over pricing, and through the Salespaq program they had financial support for advertising, incentives, and training. Of course, Sparks didn’t come cheap; he was the most highly paid individual at Compaq (even ahead of Canion). Fortunately, it turns out that he was worth the cost. Compaq was also fast in product development. After approving a product, Compaq started working on design refinements, manufacturing, marketing, and distribution simultaneously. Effectively, the entire company would pivot to the new product to get it done ahead of any competitor. This meant that retailers would always have a fresh product on their shelves from Compaq that they could price as they saw fit.

Compaq wasn’t content to merely compete in the portable business; they wanted to compete with IBM PC and XT directly. The company already had their BIOS, DOS, display adapter, and ruggedness sorted. Still, the only original feature of the Portable that would matter in the desktop arena was the display adapter, and that alone wouldn’t likely be enough to fight off IBM’s brand even if the machine were cheaper. The answer for Compaq was to use the 8086 clocked at 7.14MHz combined with 256K RAM chips. Compared to an 8088 clocked at the same speed, this doubled the speed of instruction fetching, quadrupled the execution speed of some instructions, and thanks to the higher density RAM chips, freed up expansion slots. To further distinguish their desktop machine, Compaq chose to offer tape backup. This was motivated by the 10MB hard disk that would otherwise have required around thirty floppy disks to complete a full backup. But increasing the operating speed so much over the IBM PC did create a bit of a problem as early DOS software was often sensitive to the clock speed of the computer. To circumvent this, Compaq made it possible to slow the computer to match the original IBM PC via the keyboard or via a DOS command. To indicate the current operating speed, the computer had an indicator on the front.

The Compaq Deskpro was introduced at a press event in New York on the 28th of June in 1984, and the primary concern of those in attendance was whether or not the Deskpro would be able to get shelf space. The answer Canion provided was that it’d ultimately be consumers who decided that. Just six weeks after launch, IBM announced the PC/AT 5170. The prevailing sentiment within both the press and Compaq was that this IBM machine with its shiny new 80286 CPU would make the Deskpro a failure, but that didn’t happen. Instead, the Deskpro filled out the market nicely with four models available, all of which were significantly cheaper than the IBM 5170. The Model 1 was $2495 and featured one floppy disk drive and 128K RAM. The Model 2 was $2995 and had 256K RAM and two floppy disk drives. The Model 3 was $4995 and had 256K RAM, a floppy disk drive, a 10MB Winchester disk drive, and serial/clock card. The Model 4 was $7195, had 640K RAM, a floppy disk drive, a 10MB Winchester disk drive, a 10MB cartridge tape drive for backup, and the serial/clock card from the Model 3. All of these models had a twelve inch monochrome monitor of either amber or green (maximum resolution of 720x350 pixels), an RGB color monitor port, and a parallel printer port. All models could also be upgraded to match the specifications of the Model 4 after purchase, and all featured half-height drives meaning that it was certainly possible to have two floppy disk drives, a hard disk drive, and a tape drive installed concurrently. All models also included eight expansion slots, seven of which could fit full-length cards. In Models 1 and 2, six of those slots were free, and in Models 3 and 4, five of those slots were free. Naturally, with IBM having introduced a machine utilizing the 80286, Compaq needed to respond. Both the Compaq Portable and the Deskpro received updates that moved the machines to the Intel 80286 and increased the max RAM of both lines. By the end of 1985, Compaq’s sales revenues exceeded $500 million (around $1.5 billion in 2024). At the time, this was the fastest any company had achieved that measure. There was just one issue amid all of this success, Compaq didn’t enjoy being second. While working on these 286 machines, Compaq worked closely with Intel to fix a few compatibility issues, and this relationship would be leveraged to great advantage in future products.

Sometime in 1985, Compaq had received some preproduction samples of the Intel 80386 and there were a few backward compatibility issues. Compaq worked with both Intel and Microsoft to get these resolved. Compaq, through their partnerships with Microsoft and Intel, was able to piece together that IBM wasn’t seriously working on a 386 machine just yet. As usual, the executive team gathered, they marshalled the resources of the company, and they focused on a 386 machine not wanting to cede the lead to IBM. They did this before speaking with Ben Rosen who was chairman of the board, and Rosen didn’t really like it. Up to this point, the entire compatibles market was always following and not leading. If IBM went a different direction and buyers followed them, anyone trying to innovate too much would have been wasting money. Yet, what Compaq knew and IBM did not was that people didn’t want to lose compatibility. They wanted to reuse adapter cards, reuse software, reuse disk drives, etc. They didn’t want to lose their prior investments. In the minds of Compaq, either IBM would make something compatible with prior machines and Compaq would therefore still be compatible, or IBM would make something incompatible and lose control of the market. While Rosen was shocked, he wasn’t angry. He quickly became excited just as the rest of the company had.

On the 9th of September in 1986, Compaq held a press event at the Palladium in New York. Unlike pervious events, Compaq personnel weren’t the only people giving speeches. After Canion informed the audience that Compaq was delivering the first 80386 machine, the Compaq Deskpro 386, and that it would be fully backwards compatible while improving the performance of every single component, Bill Gates took the stage. He spoke about working with Compaq and Intel to make this happen, and he also mentioned that both MS-DOS and XENIX would would be available for the Intel 80386. After BillG, Gordon Moore spoke. He too mentioned working with Compaq and Microsoft, he mentioned all of the compatibility and performance, and he then stated that Intel was capable of shipping a million 80386 chips the following year. The next two speakers were Ed Asber of Ashton-Tate and Jim Manzi of Lotus. Their talks were more about how they would be delivering software that could take full advantage of the 80386 and the Deskpro in particular. Further talks were given by both consumers and producers of technology, and Canion then closed out the event with some specific points about IBM’s potential response. His final remarks on that topic focused upon IBM needing to be either fully compatible with their previous product or offer some benefit that consumers couldn’t live without. HIs final remarks were that the Intel 80386 would build upon the benefits that personal computers had already proven, and that the while things may have felt stagnant, the Deskpro 386 showed that things had only begun. Following the Deskpro 386’s launch event, the company went on to do a large marketing campaign including an eight page ad in the Wall Street Journal, the company also sent units to many tech press outlets.

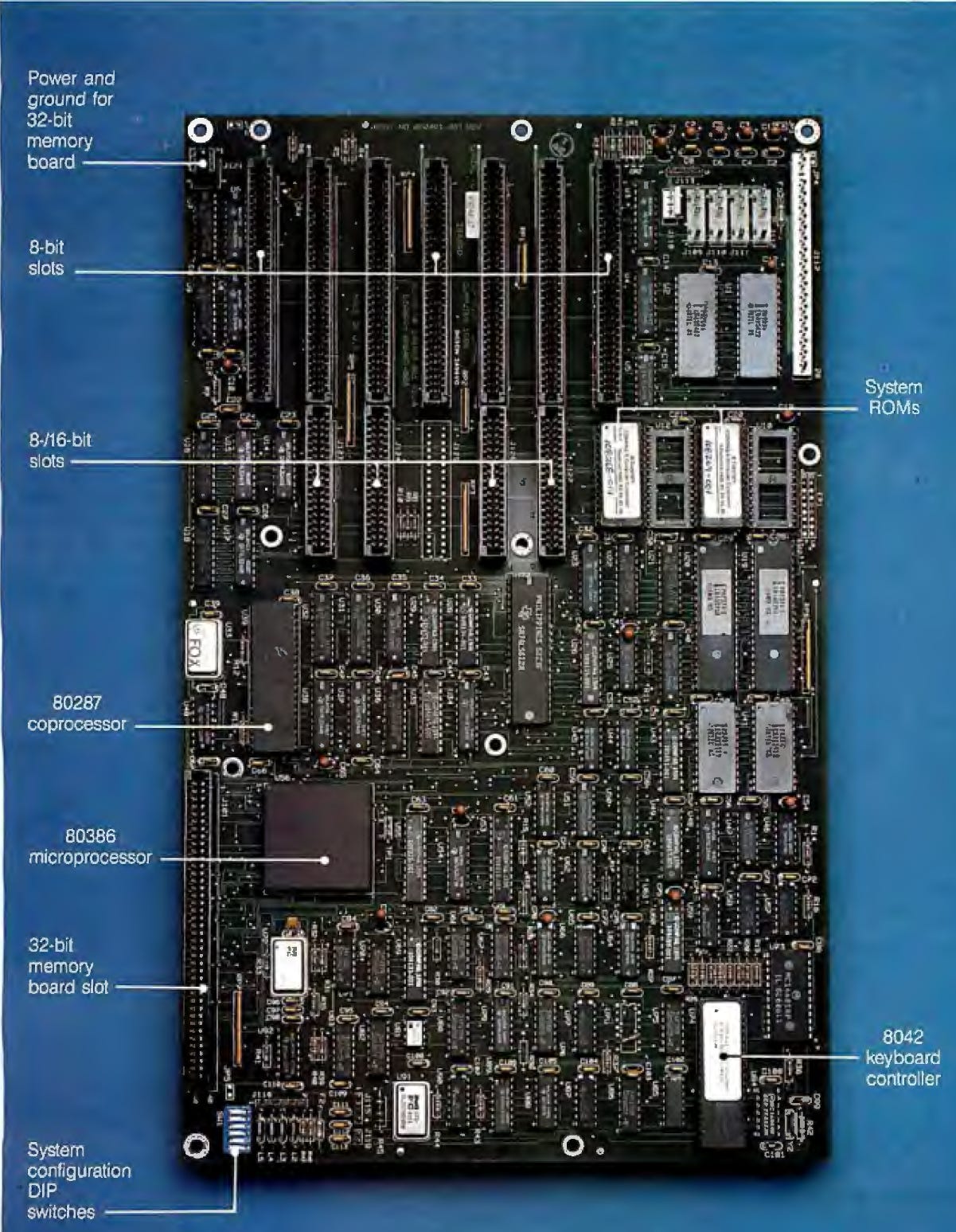

The Compaq Deskpro 386 Model 40 retailed at $6499 with an 80386 clocked at 16MHz, 1MB of RAM, a 1.2MB floppy disk drive, and a 40MB HDD. There were higher-end configurations available for increased cost. Like the original Deskpro, tape backup, more RAM, larger disks, and color graphics adapters were available. Being the very first IBM-compatible 80386 machine, four of the internal expansion slots were full-length 16 bit slots while three were 8 bit slots. The motherboard of this machine did not have a socket for an 80387, but instead offered one for the 80287. Despite having 16 bit and 8 bit expansion slots, the Deskpro 386 did utilize a 32 bit address bus. The machine could be configured with up to 10MB of RAM, and this was fast RAM. A non-paged, non-sequential access was about 100ns. For consecutive addresses utilizing paging, access times were about 50ns. The HDDs were likewise speedy for the era with 25ms to 30ms seek times on average and data throughput rates from 5mbps to 10mbps. As with the Deskpro before it, this machine could have its speed switched to 4MHz, 6MHz, 8MHz, or to its native 16MHz. Given the number of selectable speeds, this was done through the MODE command in DOS.

With consideration for the market segment this machine addressed, BYTE magazine’s Tom Thompson and Dennis Allen concluded their preview of it noting that it would really only be suitable for those individuals doing demanding work that could make use of the 32 bit power on offer such as CAD, expert systems, or next generation software development. They also noted that 32 bit peripheral cards were coming, and that these would not be usable with the Compaq Deskpro 386. Despite these remarks, they felt the machine would be a good bridge from the 16 bit era to the 32 bit era. Other press reactions were generally positive but many feared the response from Big Blue.

Computer dealers, of course, largely ignored the tech press and they kind of went crazy over the thing as did the high-end computer buying public. Compaq closed 1986 with $625 million in sales. This was double digit growth in a computer industry that overall was seeing declining sales. While IBM had brought the CP/M world kicking and screaming into a 16 bit era, Compaq was now bringing the IBM world kicking and screaming into a 32 bit era. While they were at it, Compaq stimulated a return to sales growth for the industry. In the first quarter of 1987, Compaq got updated portables to market using all of the advancements of the Deskpro 386. Compaq had wrestled the market out of IBM’s grip, but the world wasn’t yet fully cognizant of what this meant.

I have readers from many of the companies whose history I cover, and many of you were present for time periods I cover. A few of you are mentioned by name in my articles. All corrections to the record are welcome; feel free to leave a comment.