The History of Lotus

The Hardest Working Software in the World

Mitchell Kapor was born on the 1st of November in 1950 in Brooklyn, New York. He was raised on Long Island, and he graduated from high school in 1967. He attended Yale College where he studied psychology, linguistics, and computer science receiving a B.A. in 1971. He also studied at Beacon, and at MIT. While attending university, he learned BASIC, and he worked with TROLL developed by the Econometrics Project under the direction of Professor Edwin Kuh. TROLL was a mainframe software package used for econometric modelling and research which began development in autumn of 1966 and saw its first release in 1971.

Kapor bought an Apple II in July of 1978. This was neither a small nor a normal purchase for a person at that time. The microcomputer market was a hobbyist market. To quote Kapor, “there were maybe fifty Apple users in the greater Boston area, and virtually no software to make the thing useful.” With that lack of available software, Kapor found some work writing programs for Apple IIs, and he helped with organizing a user group. Among his early software products was TINY TROLL. As the name would suggest, this was a product inspired by TROLL, and it was intended for use in modelling, charting, and statistics.

TINY TROLL was at least somewhat successful as it received some good press. Benjamin Rosen wrote the following in the Electronics Letter on the 19th of October in 1979:

Very exciting things are happening in personal computer software. The most impressive statistical package we have seen so far is TINY TROLL, a multiple linear regression package from Micro Finance Systems. TINY TROLL performs the kind of statistical calculations that one normally sees only on large computers. For instance, TINY TROLL routinely will regress up to nine independent variables and one dependent variable. Moreover, it plots them in high resolution graphics on the screen for visual inspection of their correlation.

While still attending school and developing and selling TINY TROLL, Kapor was introduced to Dan Fylstra and Peter Jennings by Bob Frankston. Fylstra and Jennings marketed VisiCalc. Fylstra and Jennings offered Kapor a contract to rewrite TINY TROLL as VisiCalc add-on products. These were then VisiPlot and VisiTrend. Personal Software earned a royalty on each copy sold, and Kapor kept the rest of his earnings. As VisiCalc surged in popularity, there was a need to port the application to more platforms. Kapor was then hired on as a product manager for a couple of releases.

As time marched on, there was some trouble at Personal Software. They didn’t own VisiCalc, Software Arts did. This led to a legal dust up, and Kapor left the company in 1981 selling his software rights to Personal Software and earning him a deal of money, around $600,000 (or two million in 2023). Legal trouble wasn’t the only type for VisiCalc. The application was ported, but those ports didn’t take advantage of the hardware on which they newly ran.

For his part, Kapor really just wanted to design software. He wasn’t too interested in running a business. He grew up in the 60’s and the counterculture of that time. Business wasn’t cool. Yet, he knew that to maintain the product’s integrity as well as his own vision, he’d need to be in control. The IBM PC 5150 was released on the 12th of August in 1981. This wasn’t long after Kapor parted ways with the VisiCalc team, and Kapor made two very good judgements. First, he rightly assumed that the PC would be a success. Second, he again rightly assumed that PC-DOS would do better in the market than CP/M 86 or UCSD P.

In 1982, Kapor founded Lotus Development Corporation with eight employees, his own pile of cash, and about five million from investors. The idea was to make a spreadsheet that would utilize the increased capabilities of the IBM PC (in comparison to its market rivals). It would integrate the capabilities of an enhanced spreadsheet with data visualization tools, and it would add a word processor. This three purpose software package would give the name to the product, Lotus 1-2-3. About six months before the release of the product, Context MBA came to the new company’s attention. Here was a product that married a word processor and spreadsheet. Lotus, perhaps due to Kapor’s recent experience at Personal Software, took the opportunity to avoid any possible legal confrontations. They dropped the word processor and added a database. In hindsight, this was a more natural fit anyway.

At Lotus, Kapor was both a software designer as well as a manager. He arrived at the office around 07:30, and worked sixty hour weeks. For the actual programming work, he leaned on Jonathan Sachs. Sachs had graduated from MIT with a degree in mathematics. He’d also developed his own Forth derivative (STOIC), and then went to work at Data General and Concentric Data Systems. Like any good and enthusiastic programmer, Sachs wanted to write a language in which he’d then write 1-2-3. Kapor rightly said no. 1-2-3 was written in 8088/8086 assembler, and it was highly optimized for the 5150. Sachs did at least get to write a macro language.

Very early models of the PC shipped with a mere sixteen kilobytes of RAM. These early models were followed quickly with a base model containing sixty four kilobytes, and later the XT which had a base RAM of one hundred twenty eight kilobytes. Lotus 1-2-3 required a minimum of two hundred fifty six kilobytes, the maximum for the earliest IBM PCs. If you wanted graphics, 1-2-3 supported CGA and MDA, as well as dual monitor mode (Hercules support was added shortly after the initial release, a fact which Hercules used in their marketing). One would imagine that this would have limited the product’s success, but it didn’t. Marketing was aggressive in comparison to anything previously in the software industry. Kapor invested nearly a million dollars into a marketing campaign that included television and magazines. As far as magazines went, it was normal at the time to advertise in tech publications like BYTE. While 1-2-3 did appear in some tech publications, it also appeared in Businessweek and the Wall Street Journal. Lotus even sent people out to train the dealers who’d be selling the software at retail. Nothing of this approach had been tried before. The tech press and the financial press were fans before the product ever shipped. Kapor knew his target market quite well.

Lotus 1-2-3 was released on the 26th of January in 1983. It required a computer that cost nearly $6000 dollars (over $18,000 in 2023), and retailed at $495 (about$1500 in 2023). The company was planning to sell around four million dollars worth of software in the first year, but they instead sold $53 million (around $163 million in 2023). Just as VisiCalc had sold Apple IIs, 1-2-3 was selling PCs. Advertising alone didn’t make 1-2-3 successful. Lotus 1-2-3 could handle larger spreadsheets than the competition, it integrated the functions of multiple software products into a single product, and it was fast. Lotus Development went public on the 6th of October in 1983 raising $41 million (about $121 million in 2023). By the year’s end, Lotus Development was the second largest software company on the planet.

In the early days of 1984, 1-2-3 was hugely popular. That the program relied so heavily on the IBM PC’s design led to its use as a stress test and compatibility test for IBM PC clone makers seeking 100% compatibility for their own machines. This is, in fact, so much the case that many advertisements in trade press explicitly stated their compatibility with Lotus 1-2-3. Due to the product’s popularity and market success, the company grew quickly hitting 520 employees by July in 1984. This growth required a change in management practices. Kapor had started the company with a rather informal managerial style. He felt this was no longer truly sufficient, and in October of 1984, Jim Manzi became President with Kapor as CEO. Sales reached $157 million (about $464 million in 2023) by the year’s end with 700 people on staff.

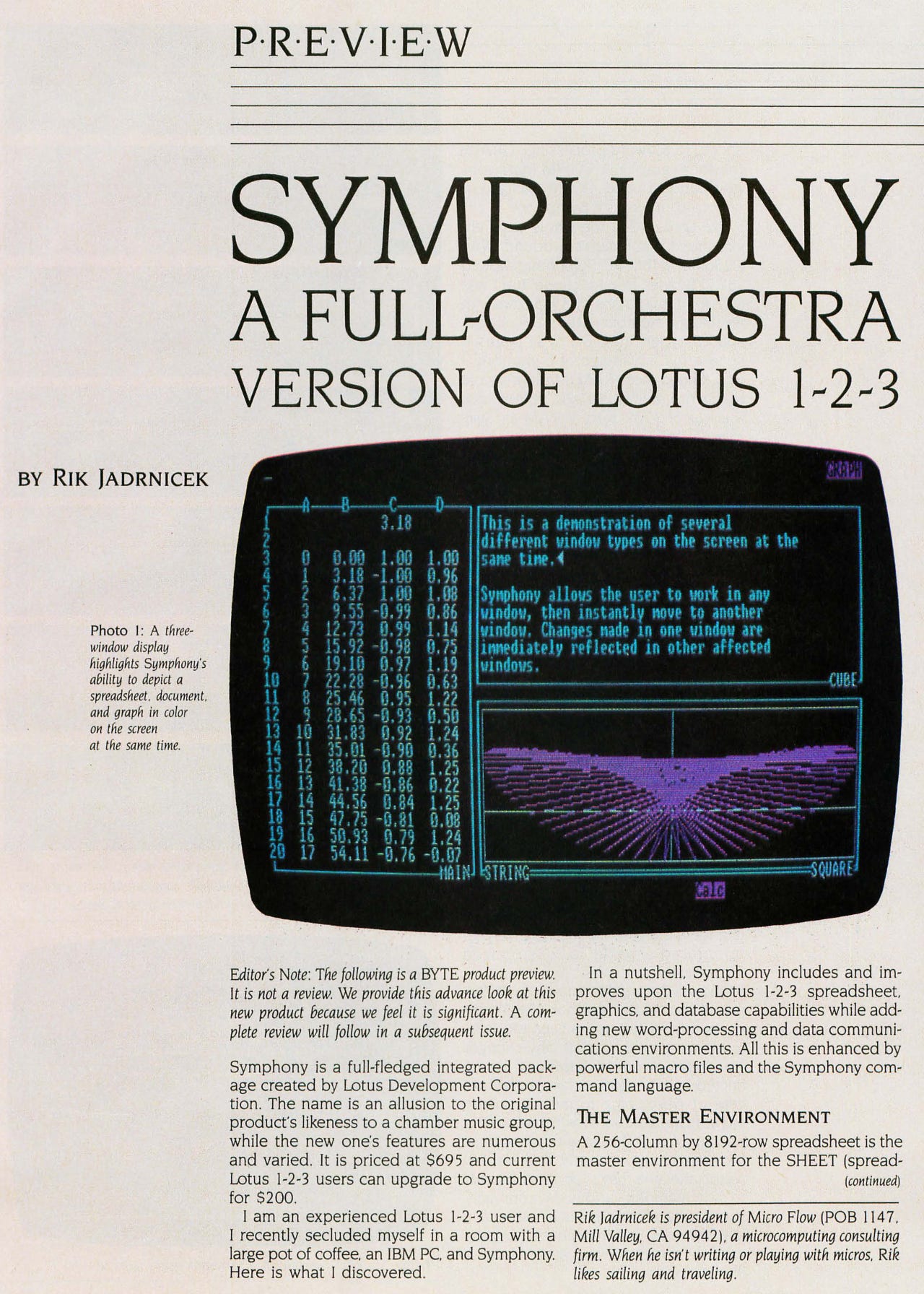

Lotus released Symphony in 1984 which was intended to compete against products like Ashton-Tate’s Framework. This was an attempt at an integrated office suite that combined spreadsheets, word processing, graphing, database management, and communications. It allowed for add-in applications like document outliners, spell-checkers, and statistics packages. In 1985, Lotus released Jazz which was a similar product to Symphony but targeted at competing with Apple’s AppleWorks on the Macintosh. Neither Symphony nor Jazz were very successful in the market, and on the Macintosh in particular AppleWorks and Microsoft Excel were dominant. Kapor said:

It was just asking too much of the Mac. It was overly ambitious, and it had bugs in it. We spent a fortune on advertising, including TV advertising, which was one of the worst business decisions I ever made. It was just like setting fire to bales of hundred-dollar bills. Jazz was a bomb. That was also the low point of Mac sales. People had just written it off. We were doing business products, and a spreadsheet was an enterprise product. The Mac in 1985 and the enterprise was a complete nonstarter. Lotus's efforts around the Mac were pathetically unsuccessful, which is sad.

In rather fitting end for VisiCalc, Lotus purchased Software Arts in 1985 for $800,000 and paid off its $2.2 million in debts. VisiCalc and its related products were discontinued. Also in 1985, Kapor handed Manzi the role as CEO, and Kapor stayed on as the Chairman. Sachs left the same year.

In 1986, 1-2-3 sold seven hundred fifty thousand copies which was far more than any competition and brought the lifetime sales of the product to more than two million. This represented nearly 18% of all business software sales industry-wide and around 60% of Lotus’s revenues. Kapor left the company in July of 1986 and sold his stake.

From 1986 to 1989, Lotus maintained its market dominance and expanded to mainframes, minicomputers, and workstations with products quite similar to 1-2-3 but leveraging the greater computing power of these targets. These definitely helped the company, but they weren’t going to be the next big thing. As history tells what these folks could not have known for certain, the PC compatible market would kill off mainframes, minicomputers, and workstations.

Ray Ozzie, Tim Halvorsen, and Len Kawell had all used PLATO at the University of Illinois. This system was used for computer-assisted instruction starting the early 1960s, and it was the birth place of many very modern ideas like message boards, online testing, email, chat, screen sharing, and multiplayer networked gaming. Ozzie, Halvorsen, and Kawell were particularly fond of the real-time communication aspects of PLATO and wanted to create a similar product. Ozzie founded Iris Associates in 1984 to develop such a product with funding from Lotus with the condition that Lotus have exclusive rights to sell the software and an option to buy the company outright. Iris began to speak of this software as groupware and it took shape over the course of three years. Lotus bought the rights to the software in 1987, and the product became Lotus Notes.

Lotus Notes 1.0 was released on the 7th of December in 1989 and featured email, calendaring, scheduling, address book, database, web server, and programming. This included both server (Domino) and client (Notes) software. Effectively, the system was a non-SQL database where users can share data. Custom applications could be written to display, manipulate, or add information within the database. This meant that in deployed Notes systems it was common to see the included applications alongside custom discussion forums, document repositories, expense approval systems, ticketing systems, and so on. Essentially, Lotus Notes was kind of like an ERP system, and kind of like Google Wave.

The first release sold about 35,000 copies. The next release was 1991, and it added rich text, a C API, and ODBC among other features. In 1993, Lotus Notes got a UI overhaul that made it look far more at home in the Windows 3 UI. Licenses had been sold to more 2000 companies, and the application gained support for Windows server, Macintosh clients, threading, full text search, and quite a bit more.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Lotus had invested heavily in OS/2 support across their entire product line. When Microsoft released Windows 3, Word, and Excel, Lotus had no offerings to compete and they suffered. Borland also brought Quattro Pro to market in 1988. The combined assault from Microsoft and Borland saw 1-2-3 drop to 55% market share by the end of 1988, with a continued falling share through the 1990s. Adding to that hurt were the royalty payments on Notes to Iris pushing Lotus to exercise their option to purchase Iris in 1994 to stop the bleeding. In March of 1990, Lotus was working on a merger with Novell Inc. who was the largest computer networking company at the time. Novell had good technology, and Lotus had a very large customer base who relied on networks with Notes. This would have been a good play for both companies. The merger would have made the new company the largest software company. However, Novell backed out as the two were approaching closure on the deal as Novell didn’t wish to become the acquired entity as the junior player. In December of 1991, Lotus laid off 400 people (around 10% of their staff), and ten VPs left the company.

In 1992, Lotus Ami Pro word processor and Freelance Graphics were receiving positive reviews, Notes was selling well, and the company looked to be positioned for new success. The company’s SmartSuite product combined Ami Pro, 1-2-3, Freelance Graphics, and cc:Mail. cc:Mail allowed a user to send an email from any of the SmartSuite applications. By 1993, Lotus was recovering, and a huge percentage of that recovery was due to Notes and it’s annual maintenance contracts and upgrade sales with large firms. But this recovery wasn’t to last, 1994 saw Lotus 1-2-3 and SmartSuite both decline sharply in sales. Microsoft’s offerings were the clear winner. The company was once again posting losses, and this prevented the company from being able to lower the price of Notes to capture more market share.

On Monday the 5th of June in 1995, IBM offered a $3.3 billion hostile takeover to Lotus Development Corp’s share holders. This was absolutely bananas. IBM was blue suits, ties, and starched white shirts while Lotus was the first company to support an AIDS walk in 1986, the first to grant benefits for same sex partners in 1992, and it offered daycare to employees with children. Despite this seeming incompatibility, the deal went through, and Jim Manzi left three months after the merger. As with other IBM acquisitions, IBM was slow to completely dominate the acquired company as they tried to leverage the new asset to their market advantage. Lotus Notes did well for a while under IBM until being outcompeted by Microsoft Exchange. Lotus 1-2-3 and SmartSuite were never quite the popular magic they had once been and withered as Microsoft Office took the almost the entire market. The Lotus brand was discontinued in 2001. All mention of Lotus was removed from IBM websites and materials by 2012. It’s interesting that Lotus 1-2-3 helped sell IBM PCs and thereby also helped Microsoft, and those two companies were then the cause of Lotus’s demise.

Mitch Kapor cofounded the Electronic Frontier Foundation in 1990, was the founding Chairman of the Mozilla Foundation in 2003, and was an investor both in many companies and in many non-profit organizations.

On a side note, I now have readers from many of the companies whose history I cover, and many of you were present for time periods I cover. A few of you are mentioned by name in my articles. All corrections to the record are welcome, feel free to leave a comment.