Works: An Office in a Single Application

AppleWorks, ClarisWorks, Microsoft Works

Early in the microcomputer revolution, the computerized spreadsheet was the first breakthrough product. This started with VisiCalc, and it continued with Lotus 1-2-3. The next step was to integrate the spreadsheet with other products. This was first done with BASIC with VisiCalc’s data files. MicroPro International took this one step further by integrating WordStar, DataStar, and CalcStar into StarBurst. This was the first ever office suite (although there was also The Incredible Jack from Business Solutions the same year, I believe MicroPro was first). MicroPro’s issues in the market largely kept StarBurst from being more successful than it otherwise might have been.

Still, first VisiCalc and then Lotus pushed sales for computers generally. WordStar and other word processing applications after it combined with falling microcomputer prices to replace both typewriters and electronic word processors. At this point in the early mid-80s, a key problem was that people were forced to learn the keybindings and menus of each program. These were typically radically different from one another. The average person seeking these productivity improvements would go to the store, buy a computer which was incredibly expensive, buy software which was expensive, and then spend a large amount of time reading both the computer and software manuals to learn how everything worked. Today, we are blessed with several decades of research, focus groups, trial and error, and iteration to provide certain common shortcuts, visual design paradigms, and other unifying characteristics for productivity software. This wasn’t the case then (and arguably wasn’t until the mid-90s). As Steven Sinofsky has told us, people were just trying to make stuff that worked in the early days of the PC market. There was no paved road for would-be technology professionals to follow, people had to grab a machete and hack their courses through the jungle.

This was the state of things when AppleWorks, written by Rupert J Lissner, was launched. Rupert saw the in-development office system on the Lisa, and he felt that combining the database, spreadsheet, and word processor into a single program would have certain benefits. Work on what would become AppleWorks started in 1982 in 6502 assembly language targeting the Apple II and the Apple III. The program made certain concessions. WordStar was certainly a more powerful word processor than AppleWorks, Lotus was certainly a more powerful spreadsheet, but AppleWorks delivered enough power to the average user to get the job done. It would also work with just the 64k base RAM of the Apple IIe. It could, however, take advantage of larger amounts of memory (up to 2MB), or swap to disk when needed.

As far as the design of the application is concerned, it used menus that could be navigated with arrow keys, and a selection could be made by pressing the enter key. AppleWorks also had a clipboard for sharing data between files. Much of the interface research had been done by Apple during Lisa’s development and this information was made available to Lissner for AppleWorks.

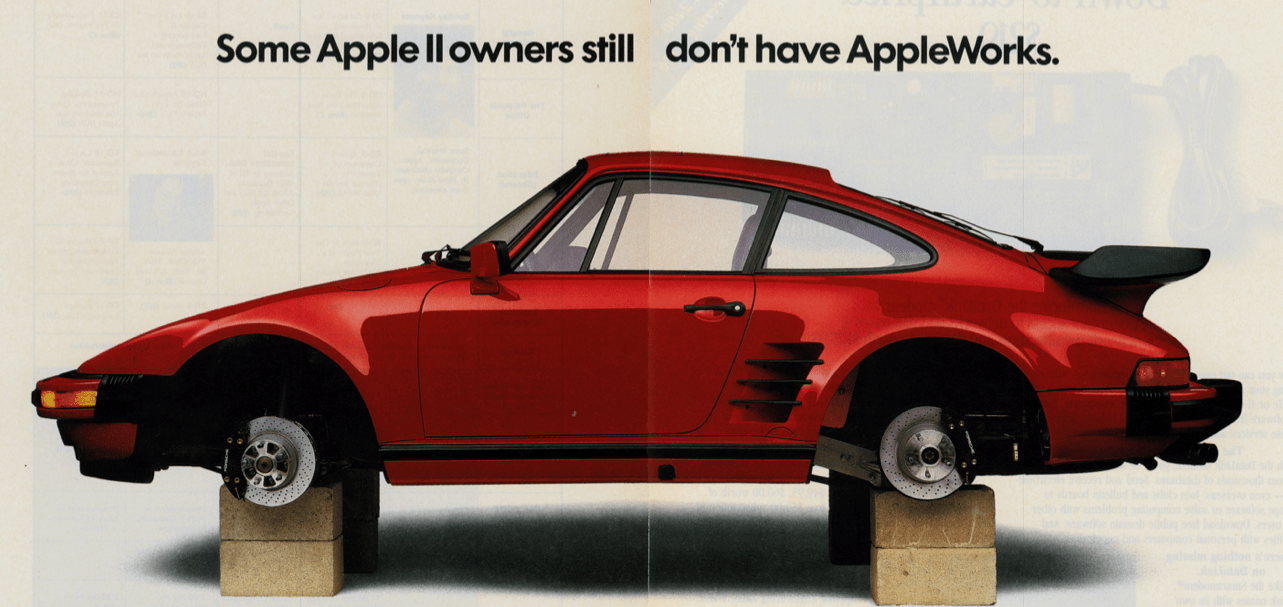

By the time AppleWorks was released, Apple had completely shifted its focus to the Macintosh. Apple II software simply wasn’t much of a concern to them. Despite a lack of marketing, AppleWorks was a market success. By the end of 1984, sales for AppleWorks were ahead of even Lotus 1-2-3 making AppleWorks the best selling piece of software in the world for a brief time.

In 1987, AppleWorks was moved into an Apple subsidiary called Claris. This would result in the release of more versions of AppleWorks for the Apple II as well as the release of AppleWorks GS for the Apple IIGS in 1989. The code for AppleWorks GS had a separate origin. This was from StyleWare which Claris acquired in 1988. This version did, however, have the ability to use the same file formats as the older AppleWorks releases. In 1991, Claris released ClarisWorks for the Macintosh and for Windows. Claris was dissolved in January of 1998, and Apple then revived the AppleWorks name for the ClarisWorks-derived suite of productivity software. This too came to an end with a rebranding to iWork.

Lissner hadn’t stayed to become part of Claris, he left shortly after creating AppleWorks. Rupert teamed up with a former IBM employee Don Williams who’d created Desktop Plan and Graph'N'Calc for the IBM PC, and the two were hoping to recreate the success of AppleWorks but for the Macintosh. The company that they created for this endeavor was named Productivity Software… I suppose that this is exactly the kind of name one would expect from IBM. They almost immediately began hiring. The first employee was Michael Watson who was tasked with creating the database component. They then hired Brian Haas to create the word processor component, and Tim Lundeen to create the spreadsheet. Linden and Watson would then write the system by which all of the pieces would be integrated. After some time, Ben Halpern was hired to work on charting and drawing for this suite. Lissner didn’t last long with Productivity Software. He was flush with cash from the success of AppleWorks, and he didn’t seem too interested. In 1986, Bill Gates visited Productivity Software in Santa Cruz, and he proposed that Microsoft publish the software suite as Microsoft Works for the Macintosh. This worked well for all involved and the first release was made that same year, 1986.

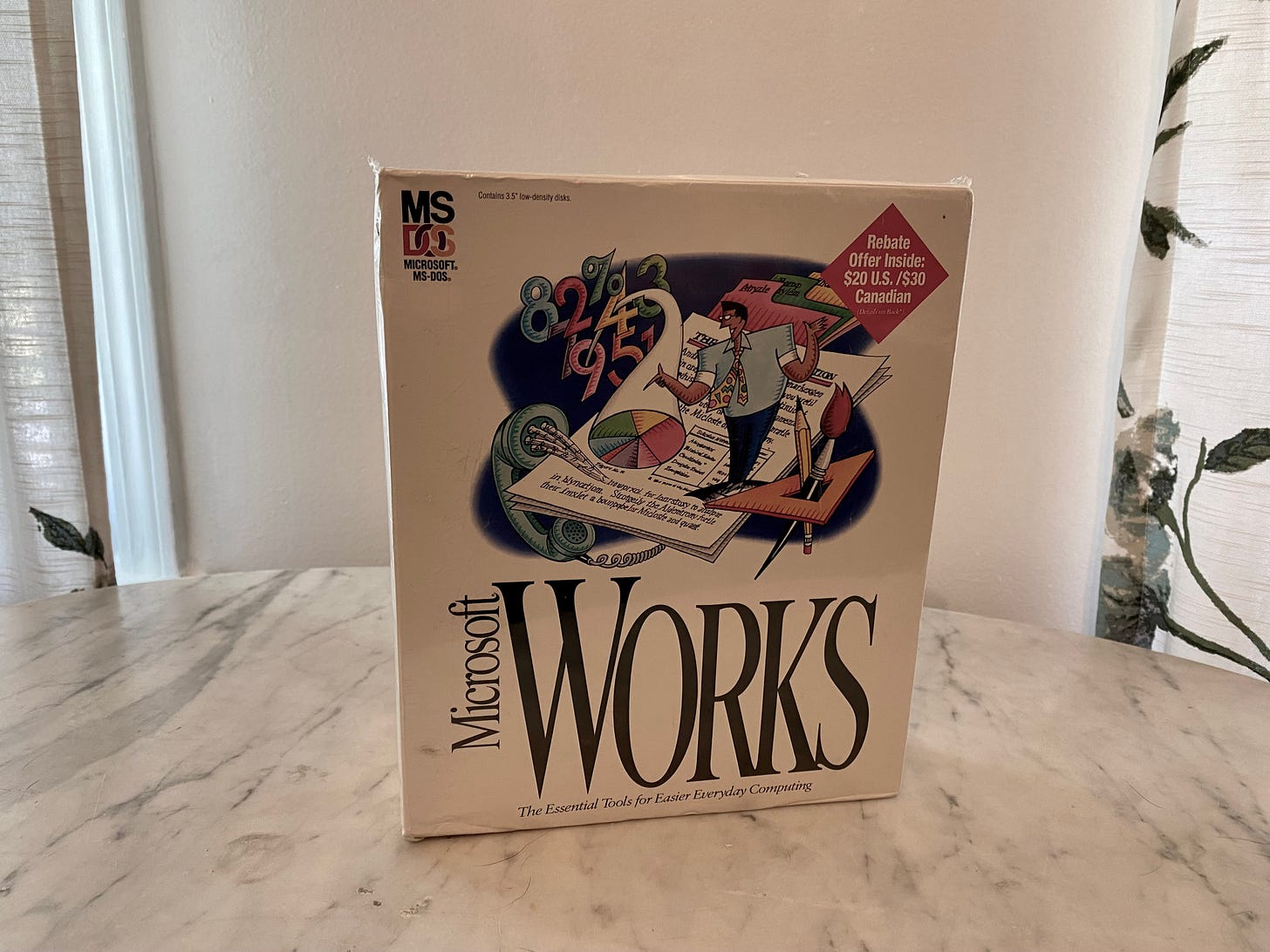

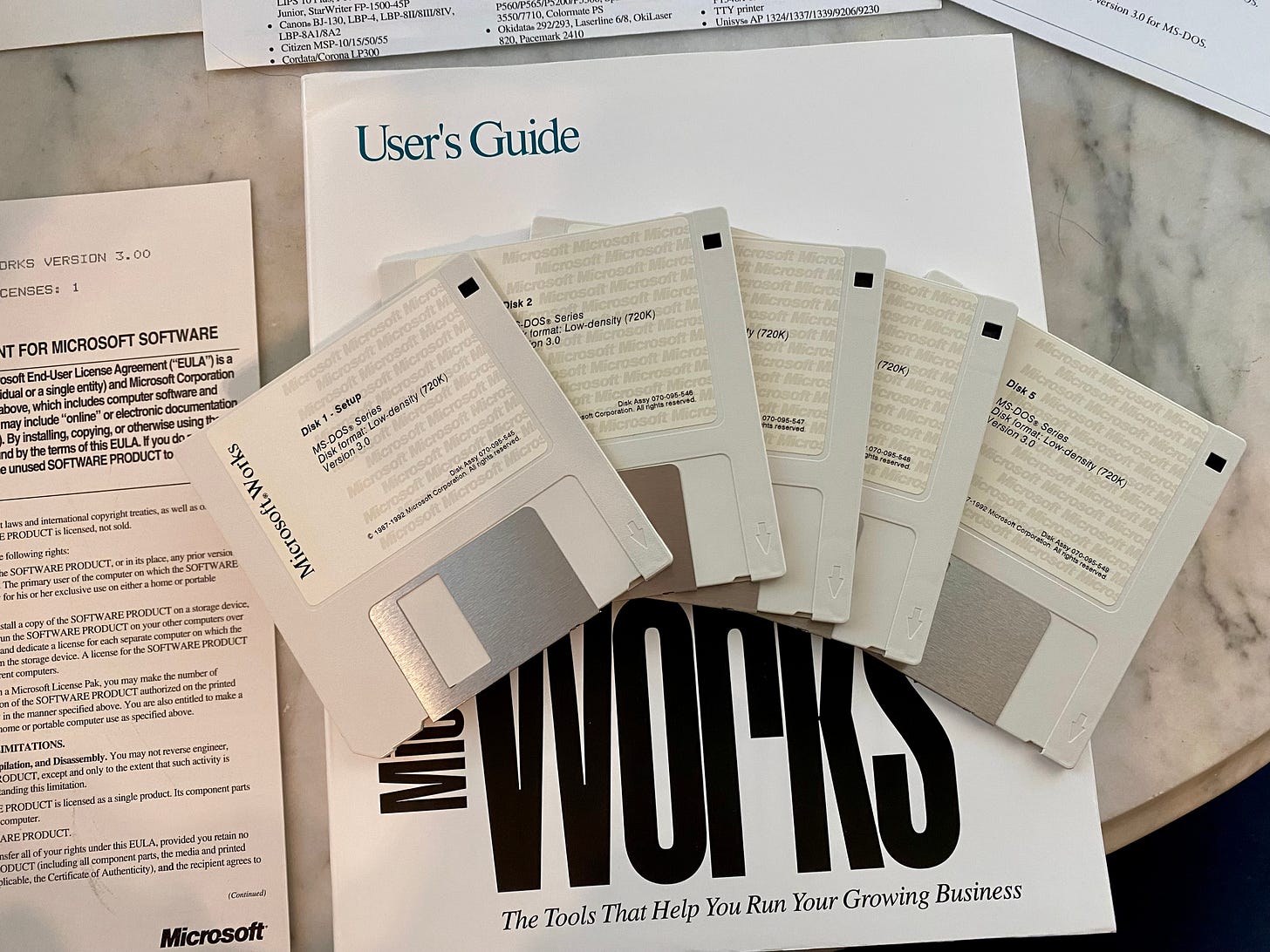

Productivity Software would make two more releases of their suite before Microsoft bought them out. A version of Microsoft Works for MS-DOS was released in 1987 requiring just 256K memory and an 8088. Version 2 for DOS bumped the memory requirement to 512k in 1990. Version 3 in 1992 bumped the memory requirement to 640k.

I am very much not a fan of Microsoft’s naming of their first Windows release. Microsoft Works for Windows 2.0 was released for Windows 3.0, and it required a 286 with 1MB of RAM. Works 3 for Windows required Windows 3.1, a 386, and 4MB of RAM.

Throughout all of this, Works was a single monolithic program. It saved disk and memory by reusing as much code as possible and making each component of the suite just a window within a larger program. Version 4.5a required just 6MB of RAM and 12MB of disk. This ended with the release of version Works 2000. After this point, Works became more of a cost-reduced analog to Microsoft Office, and in 2009 Works was completely discontinued. Microsoft filled the market segment by releasing Office 2010 Starer Edition.

Personally, Microsoft Works was the first office suite that I used to any extensive degree. I used it first in my school’s computer lab on Macintosh. Later, when my father gifted my very own Windows 95 PC, it had Microsoft Works as well. Works was more than enough for a child’s needs, and revisiting the software as an adult in MS-DOS or on Macintosh, I appreciate the simplicity and utility and the suite. It’s well designed, it’s get the job done, and it’s relatively reliable.

Interesting read. I had no idea that AppleWorks came before ClarisWorks before returning, nor did I know about the relation between AppleWorks and Microsoft Works. This article came at the right time! I just recently started using AppleWorks 6 a little while back on my G3 Mac, and actually just installed Works 2001 on my Windows 2000 machine yesterday. I grew up with Office 97 -- and later, Office XP - so I'm pretty new to it, but I do like it. Also, I'm not sure if you've tried it, but AppleWorks 6 did have a Windows port, but it didn't seem quite as good as the Mac version.