Life on Chiron

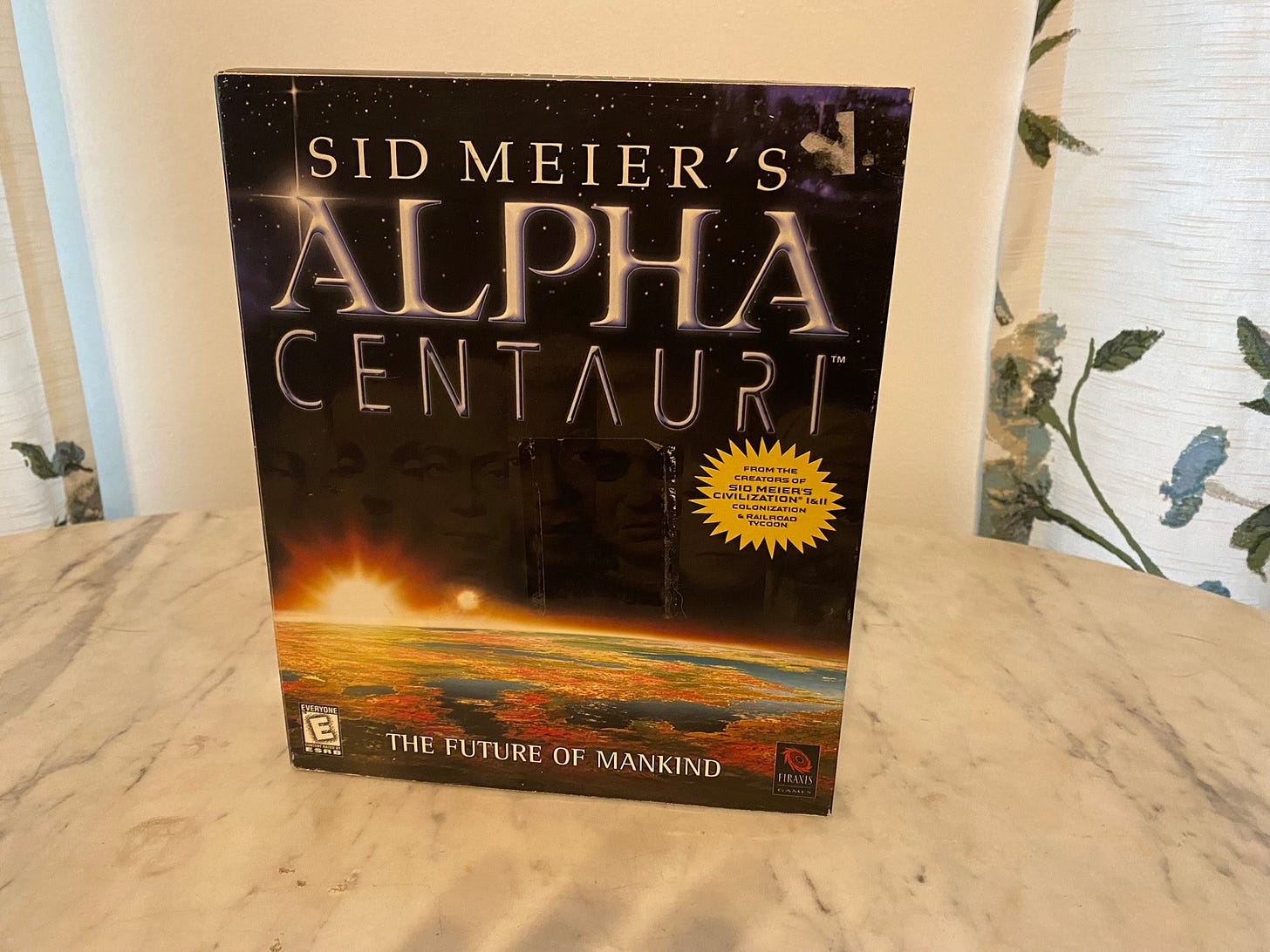

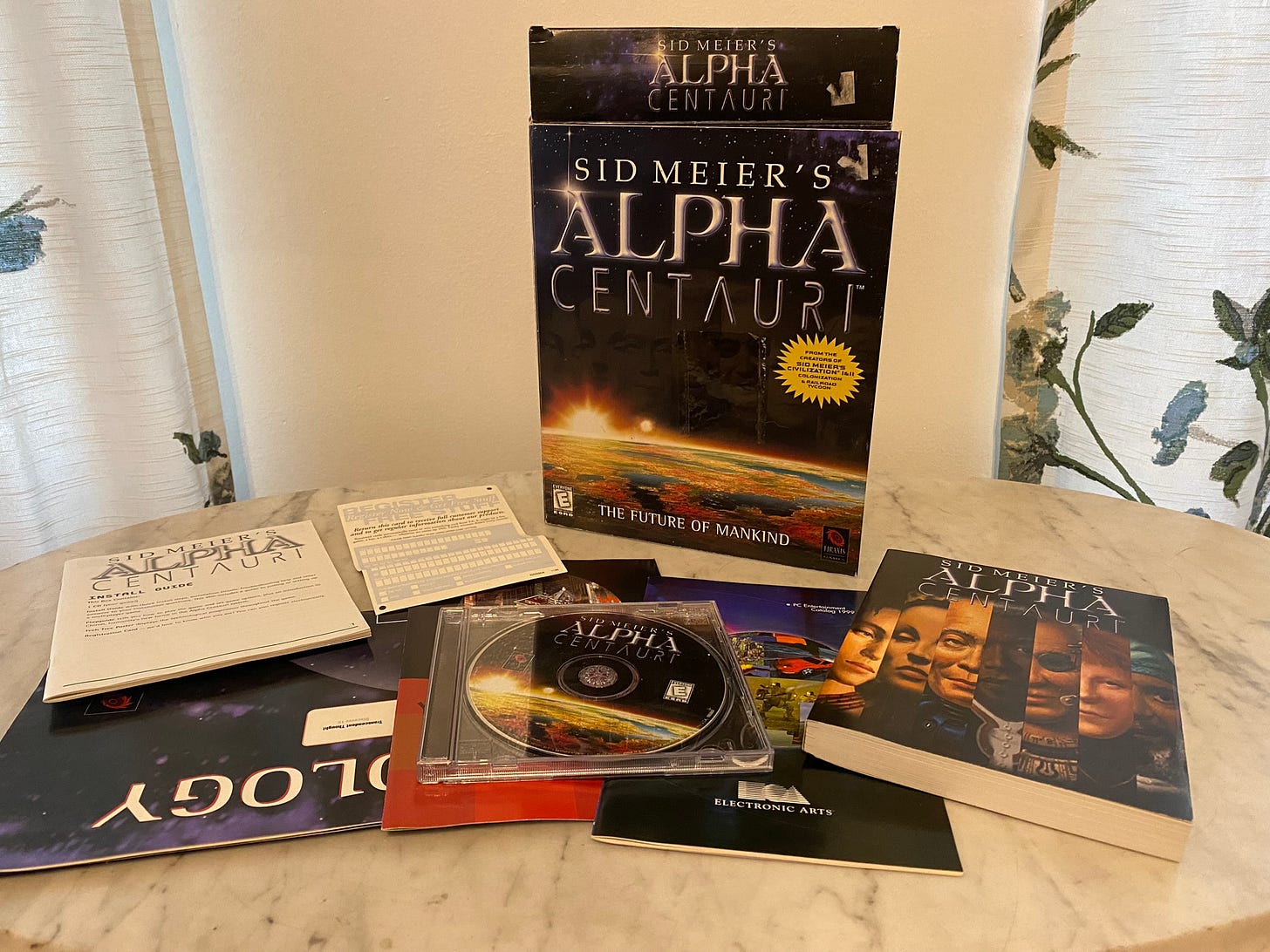

Sid Meier's Alpha Centauri

Firaxis Games was founded on the 1st of May of 1996 by Sid Meier, Jeff Briggs, and Brian Reynolds after they finished up their work on Civilization II and left MicroProse. From the start of their new venture, they knew they’d do just game design and development leaving distribution and marketing to outside contractors. Ultimately, they chose to publish their games with Electronic Arts under the Origin Systems label. Development of a sequel to Civilization II started in July of 1996 with Brian Reynolds leading development just as he had on the most recent Civilization title. The first year of development was largely a year of prototypes due to work on Gettysburg! taking the majority of the developers’ time. This wasn’t at all abnormal anyway. At Firaxis, and at MicroProse before it, development of any new game started with a rapid iteration of many playable prototypes that enabled the development team to test ideas. Once they had something that was working well, they started “surrounding the fun.” This means that they leaned into those parts of the game that were fun, and they removed all of the parts that weren’t fun.

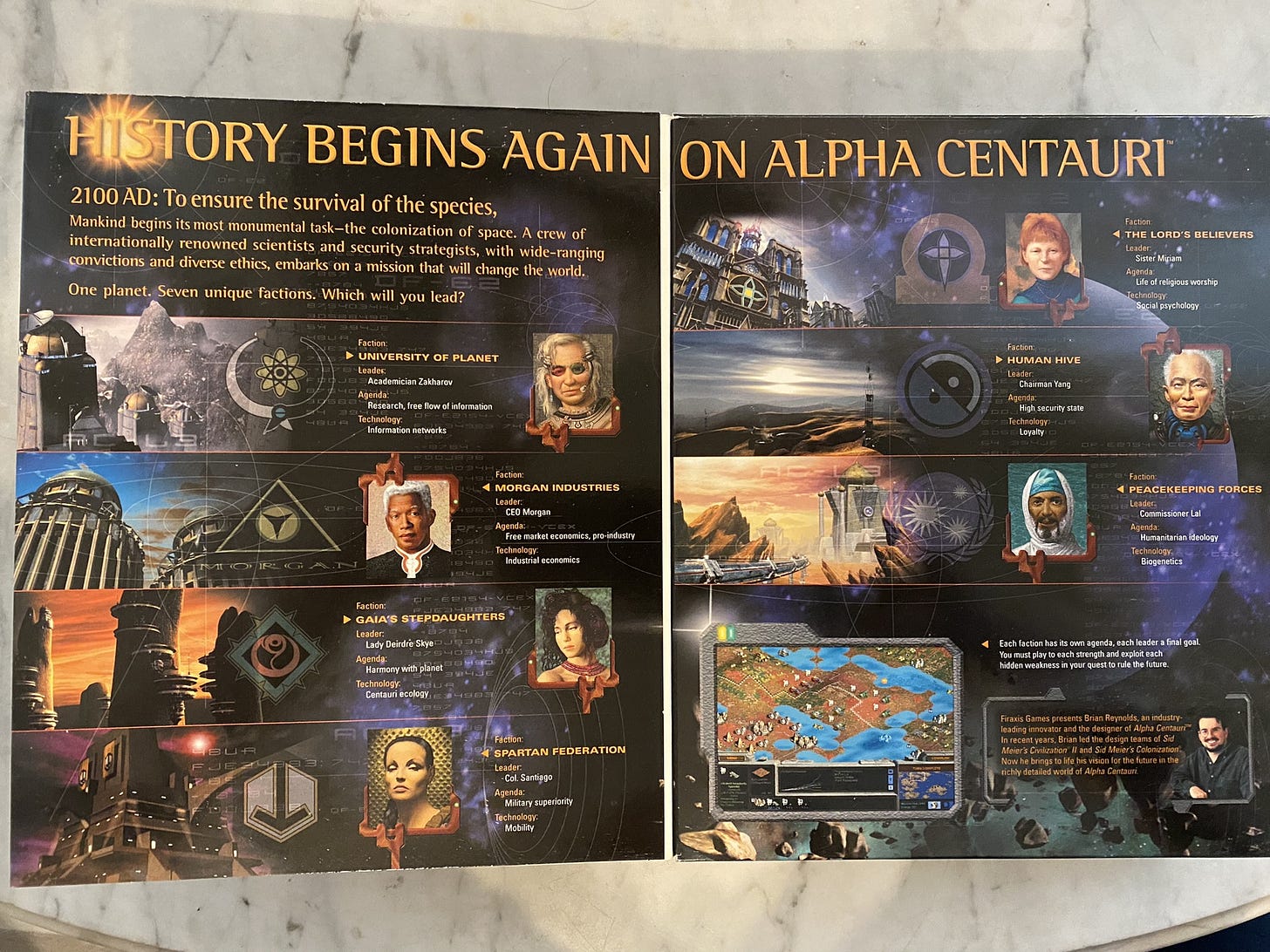

In Civilization II (and other Civilization titles), there is a victory condition in which a player sends a manned flight to Alpha Centauri. In a bit of rather dark commentary on the nature of mankind, the captain of the starship Unity is assassinated, the ship damaged, and the people on-board split into seven different ideological factions. They then descend to their “new” planet, Chiron, and they start repeating the mistakes of the Earth they left behind, battling for supremacy of the new world.

This is still a Civilization title, but things have new names. Cities are called bases, city buildings are called facilities, wonders are called secret projects, barbarians are mind worms, but the overall gameplay remains explore, expand, exploit, and exterminate. Yet, Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri (SMAC) has a fanbase that is more vocal than most other games in the Civilization series, and this due to two things: improvements over the first two entries, and the story. On the improvements front, there are new mechanics. The player has the ability to customize units (to a point), terraform the landscape, and install governors at bases. Diplomacy is upgraded over the game’s predecessor, and the map editor is likewise better. The game features quite a bit of voice acting to provide depth to the world. This voice acting is heard upon completion of a Secret Project or when completing a base facility.

The most memorable voice over for me when completing a base facility is the one from the recycling tanks:

"It is every citizen's final duty to go into the tanks, and become one with all the people."

This definitely gives me a bit of a Soylent Green vibe.

There are also interludes where a bit of text narrative is presented that adds tons of “feel” to the game. Reynolds had initially wanted these to be cutscenes, but money wasn’t there. Playing SMAC becomes the story of settling and conquering an alien world. That conquering is not only the conquering of human civilization but also of the Xenofungus.

No matter the side that one chooses, he/she is beset by fungus. In interludes, a mysterious voice is communicating with the player. This voice threatens more attacks from the mind worms should pollution and corruption continue. This global intelligence doing the communicating echoes the Gaia Theory a bit: the planet is shaped by the livings on it, which in turn shapes the living things in feedback loop. This specific interaction provides some very interesting developments throughout the game.

For this story and for the science fiction setting more generally, Reynolds cites Frank Herbert’s The Jesus Incident, Hellstom’s Hive, and Dune, Vernor Vinge’s A Fire Upon the Deep, Larry Niven’s and Jerry Pournelle’s The Mote in God’s Eye among other works of science fiction. Reynolds also says the nature of science fiction appealed to him. Working with Meier normally means historical games. This is fine with Reynolds who does have a degree in European history, but he’d also briefly pursued graduate studies in philosophy and the ability to return to that field was refreshing for him. These motivations and influences are felt, seen, and heard throughout the game. In government types and social engineering, in the story, in the technologies, in the interactions between factions, in the factions’ varying ideologies, in the voice over work, the love of both science fiction and philosphy is unmistakable.

Once the game was getting into a semi-final state, the team chose to do something they’d never done before: a public beta. This beta essentially expanded the prototyping feedback loop to a much larger player audience. This process allowed the SMAC development team to add a few features, fix a few bugs, and make improvements to the game’s interface.

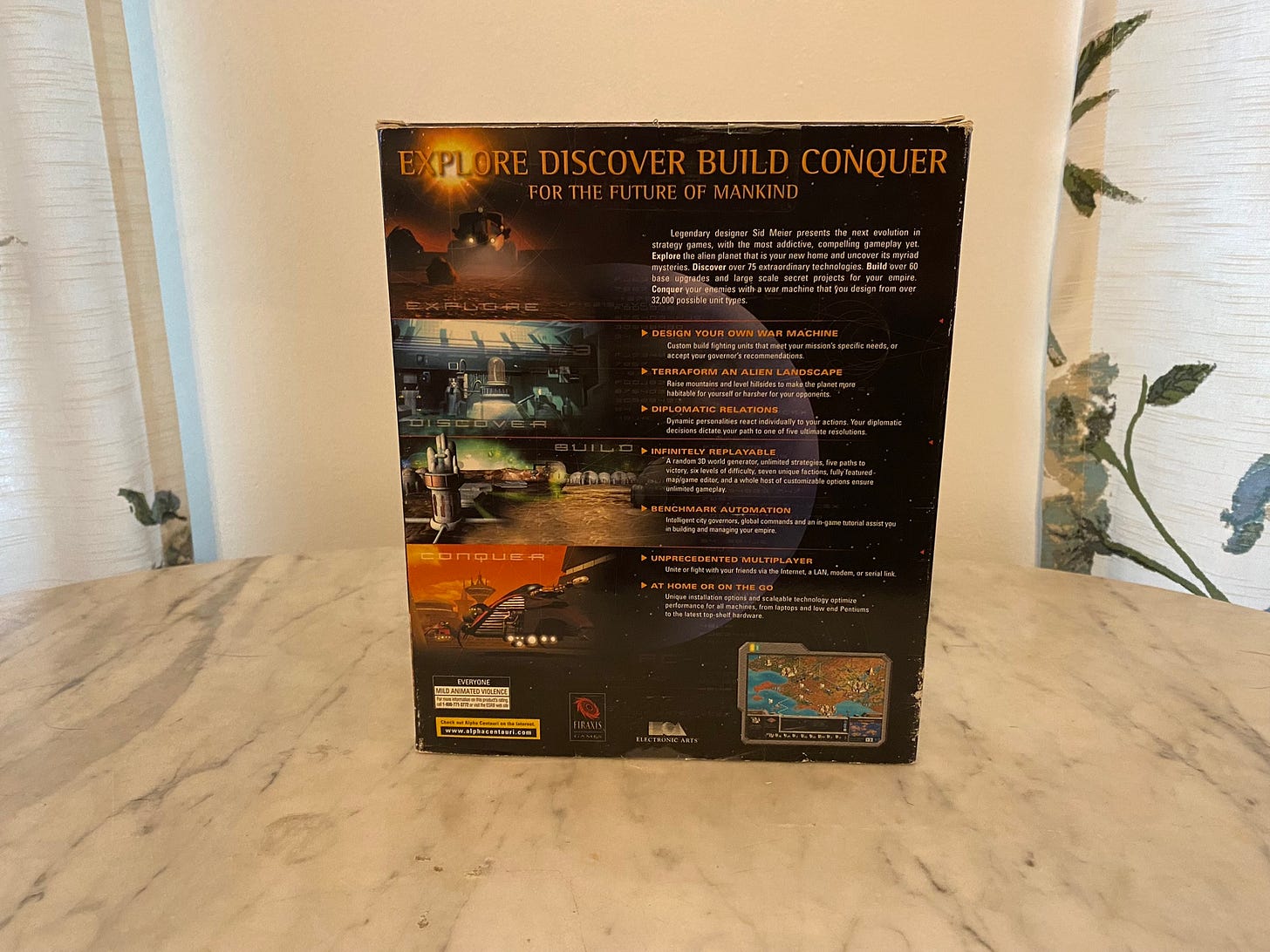

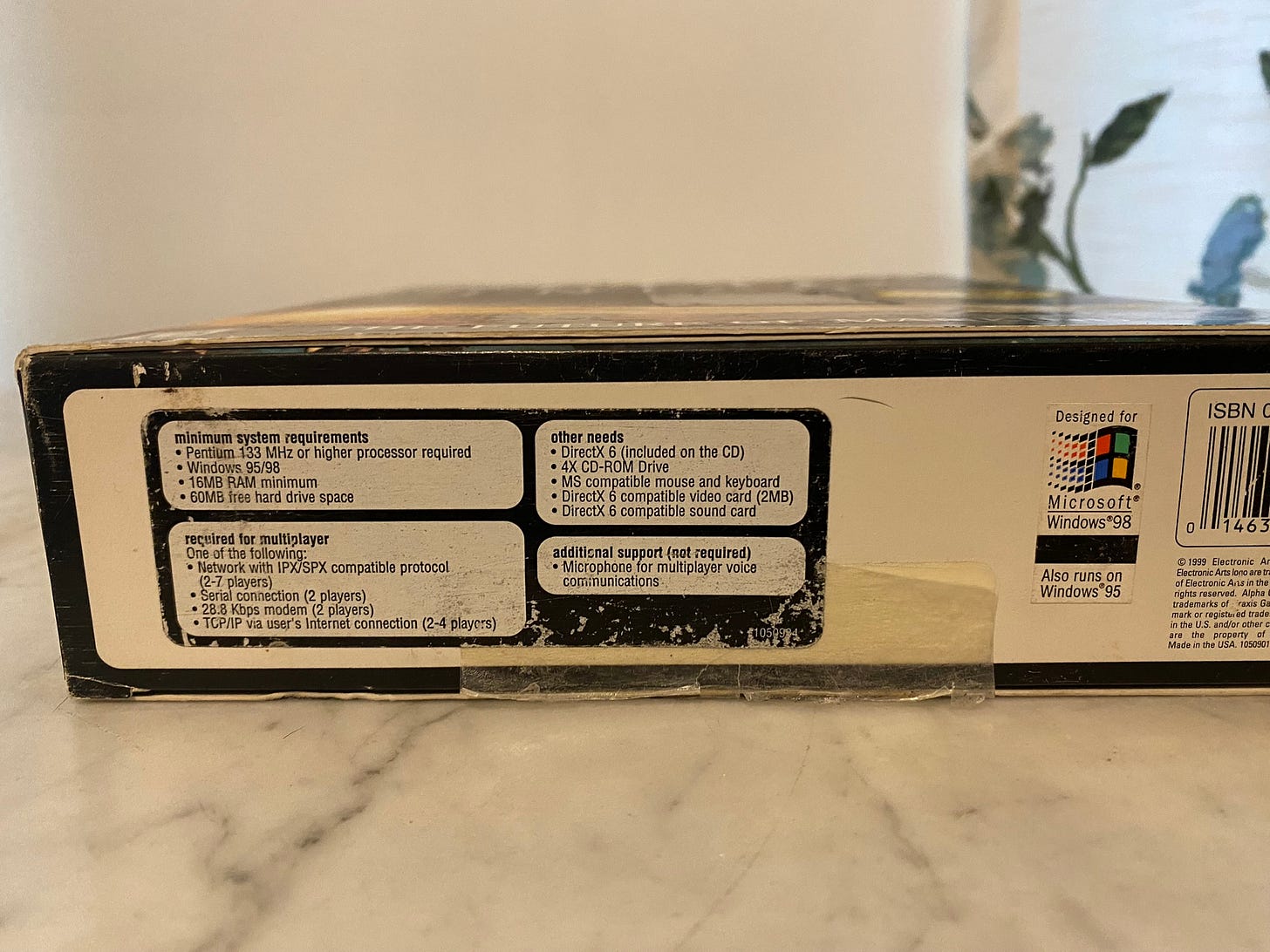

Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri was released on the 12th of February in 1999 for Windows 95 and 98. It required a Pentium clocked at 133 MHz or higher, 16 MB of RAM, 60 MB of free disk space, DirectX 6, a 4X CD-ROM, mouse and keyboard, and both a video card and an audio card that were compatible with DirectX 6. For multiplayer (2 players), a player’s machine would need either a serial connection, or a 28.8 Kbps modem. If the players were having a LAN party, then IPX support (2-7 players) was available, and for those who wanted to play online, TCP/IP support (2-4 players) was also present. It wasn’t the best selling game by quite a margin, but it wasn’t a failure. The first calendar year on the market, the game sold a respectable quarter million copies.

While this isn’t the level of success had with Civilization II, it wasn’t in the same position as Civilization II. Reynolds cites the very recent release of Windows as part of the prior game’s success:

People remember Civ2 because they loved playing the game, but one of the hidden stories is it was actually a very accessible piece of software to a much larger audience because it was Windows and it went along with Windows 95, and every new system that was coming out was being sold with Windows 95, and our game was easy to run.

This was not one of the first titles for Windows 95 like the previous title was. Additionally, there was a bit of both positive and negative press surrounding SMAC, with some saying that it was more of the same (a sentiment that I can understand, but with which I completely disagree). The lower sales figures are understandable given both points.

For me, Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri is among the best games I’ve ever had the pleasure of playing. It’s one that can still grab a day away from me if I’m not careful about my time.

Having now established a secure perimeter, we've made ourselves relatively safe from enemy incursions. But against the seemingly random attacks by Planet's native life, only our array of warning sensors can help us, for the mind worms infiltrate through every crevice and chew through anything softer than plasma-steel.

— Lady Deirdre Skye, voiceover after building perimeter defense

I came across this game early because Loki Software had ported it to Linux, and it was one of the few games a young Linux nerd could play. I have since then installed it on all my machines when I am looking for a few hours to waste away in the ambience.