The History of Caldera, Part 1

A Failing Startup and Setting the Tone

Ransom H. Love was the youngest of seven. He was born in Seattle, but his family quickly moved to Portland after his birth. At five, his family moved to Tucson as his father took a job as a civil engineer at Davis Monthon AFB. He spent his teen years on a farm, and regularly attended church services. As is normal for older teenagers in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, he served as a missionary. His trip was to Viña del Mar in Chile. He learned some Spanish, and he learned quite a few lessons on humanity, service, faith, and himself during his two years there. Upon returning to the USA, he married Nyla Stein, continued his education, and he and his wife conceived their first child.

Like so many men, the pressure to provide for a family was the catalyst for Love’s career. He moved his family to Houston where he began working for CPT. The company made computers marketed as word processors, but these machines ran CP/M and the company sold accounting packages for them. This job took him to Fairbanks where Love did well, but he then had the urge to complete his education. His family was moving once again, but this time to Provo. He finished his college degree at Brigham Young where he received his BA in International Relations, and he went to work for Sanyo.

Love was hired by Sanyo to teach people about UNIX. He actually didn’t know too much about the system himself, but he learned quickly. Sanyo was using UNIX on Motorola 68000 systems and their UNIX distribution included the PICK database. While still new to the company, Love noticed a market opportunity for Sanyo. Novell’s NetWare was growing rapidly, and could benefit from Sanyo’s disk subsystem. Specifically, he thought the disk subsystem could be sold as an intelligent disk cache for Novell networks. The VP of marketing agreed. At nights during this time at Sanyo, Love was completing his Master’s in Business Administration at Brigham Young, and he and his wife welcomed their fourth and fifth children into the world.

Willy Donahue, who was a product manager at Sanyo, contacted Love and told him that Novell was looking for a product manager who knew both UNIX and RISC for a new NetWare release. Love applied and was hired. In this position, Love was responsible for maintaining Novell’s relationships with HP, Sun, IBM, and Apple and getting them to agree to port NetWare to their systems. This work put him into contact with Bryan Wayne Sparks who was working on porting NetWare to the MACH micro kernel and with Rob Hicks who was in charge of the technical legal team. Love arranged a lunch with the two, and the trio discussed Novell’s market position with Microsoft’s rising control of the desktop platform. The strategy that these three developed was to build a desktop Linux operating system that would utilize NetWare’s networking services. The group felt that by leveraging Linux they could dramatically reduce the cost of operating system development and allow developers to spend time only on those things that they felt needed the most attention. Unfortunately, no one within Novell’s executive leadership liked this idea. The common refrain was that OS/2 had failed despite IBM’s massive budget and huge team, why and how then could anyone possibly expect to compete in that space? Through 1993 and 1994, the team built a skunk-works project pooling talent from around Novell. They ported a webserver to NetWare along with an IP/IPX gateway, and they even turned WordPerfect into a type of server-side application. Essentially, Novell rejected all of this.

In October of 1994, Bryan Wayne Sparks and Ransom H. Love founded Caldera with venture capital funding from the Canopy Group. The company was officially incorporated on the 25th of January in 1995 in Provo, Utah. This new company would continue the work that they had started within Novell. Caldera was interested in a delivering a competitive desktop operating system, and they explicitly wished to leverage the open source ecosystem to reduce time to market and reduce development costs. They chose to use Red Hat as the basis for their system as this would provide them with the RPM packaging system. Love and Sparks flew to Connecticut to meet with Bob Young. At this time, Red Hat was making a new release every two to three months. This pace was far too quick for anyone to successfully develop, test, package, and release software, and Caldera needed Red Hat Software to slow down. Caldera and Red Hat successfully struck a deal that Red Hat would make a release only once in any period of six to twelve months, and in return Caldera’s improvements to RPM (which were already underway) were provided back to Red Hat along with some money to continue that development.

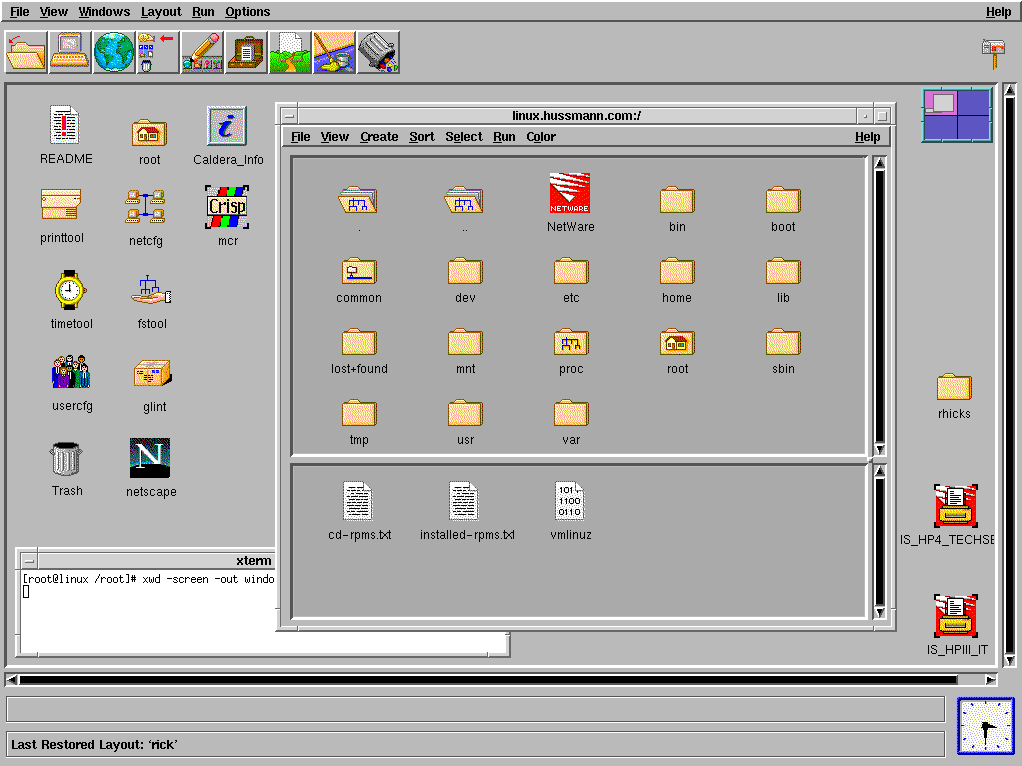

Caldera was a team of just five individuals including Sparks, Love, Jim Freeman, Ron Holt, and Nick Wells. It took them six months to make their first product, Caldera Network Desktop. They licensed, ported, and modified a GUI product from Visix Software in Arlington called Looking Glass, ported and integrated NetWare, ported Willows APIW to enabled cross platform software development on Network Desktop, and included the LISA installation and administration program from LST (a German Slackware derivative). At this time, Caldera also began providing hardware to Alan Cox to support his work on SMP for the Linux kernel. Rather than shipping XFree86, Caldera’s Network Desktop made use of XI Graphic’s Accelerated-X and the Motif toolkit.

The system requirements for Preview Release I were 140MB of HDD space (another 16MB was required if a swap partition were desired), 8MB of RAM (16MB was recommended), a CD-ROM drive, and a 3.5 inch floppy disk drive. Preview I was released in May of 1995 with kernel 1.2.8 at a price of $29.95 with a $10 shipping and handling fee (together these two costs would be around $80 in 2023). This release was followed by Preview II in September with a kernel version bump to 1.2.13. Customers who’d already purchased Preview I received this release for free if they sent in the registration card from the previous release.

Caldera priced Network Desktop 1.0 at $99 (around 199 in 2023). The official release day is noted as the 5th of February in 1996, and the announcement to comp.os.linux.announce was made on the 15th. There were promotional bundles available that included WordPerfect and other software. Network Desktop sold around twelve thousand copies, and while Caldera viewed this as a failure, the market for Linux wasn’t exactly huge. Oddly, the use of Red Hat as a basis for the product forced Caldera and Red Hat to part ways. Red Hat’s recognition grew as a result of Caldera’s product, and Young wanted to get back to more rapid development while Caldera wanted more control of their system. The two companies parted ways shortly after the 1.0 release.

Phil Hughes wrote in the Linux Journal on the 1st of June in 1996 that Caldera Network Desktop was neither Slackware nor Red Hat. It was a system designed for the end user who didn’t know what Linux was, but he also mentioned that the inclusion of NetWare might be a good way to get the system on desktops in offices. Generally, Hughes felt that this was a rather solid product with a good market niche. He also tells us that in the box he found a manual, a CD in a jewel case, a mouse pad, and two floppy disks. The CD contained the distribution and the floppies were boot disks. One disk was for booting on a standard desktop and the other was for laptops with PCMCIA cards.

There’s quite a bit of weight in that little Netscape icon on the Network Destkop. Caldera signed a multi-million dollar contract with Netscape to allow Caldera to port their browser and server products to Linux. This provided Caldera with an exclusive license to sell and distribute the Linux ports. Caldera was then able to establish a position as a reseller of Netscape’s technologies. The company had one customer in Turbo Linux and they were close to a deal with Red Hat. Unfortunately, Netscape then released the browser free of charge, and Caldera lost a ton of money. Netscape also took the code that Caldera had written for the port and merged it into their own source tree without compensating Caldera for their prepayment of royalties on licenses.

Sebastian Hetzie in Germany had introduced Caldera to the group of engineers who’d built the LST distribution and LISA. Having parted with Red Hat, Caldera purchased LST. Caldera also wanted to have some kind of compatibility with the existing PC market. This was first seen with the inclusion of Willows APIW, and then again on the 18th of November in 1996 with Caldera’s port of Wabi from Sunsoft which enabled the use of Windows 3.1 software on Linux. Apparently, Caldera really wanted to go down this road. Caldera was intent on delivering a business software solution, and this required them to have broad compatibility with existing software. At this time, DOS applications were the way to do this. Solutions existed for running DOS applications in Linux, but Caldera would then require a DOS system to include in their release.

On the 23rd of July in 1996, Caldera purchased Digtal Research’s assets from Novell and filed an antitrust lawsuit against Microsoft seeking compensation for damages resultant from “illegal conduct by Microsoft calculated and intended to prevent and destroy competition in the computer software industry,” in addition to the cessation of said illegal and anti-competitive practices. There were many claims in this lawsuit, but there are two I find most interesting. One of them alleges that Microsoft’s announcements of products that were vaporware were timed to thwart interest in competitors’ products. The second surrounds Microsoft’s display of error messages when trying to run Windows 3.1 on DR-DOS. According to Ransom Love, this lawsuit was required by Novell as a condition of the sale:

Novell would not sell Caldera the DOS asset unless we filed an anti-trust suit against Microsoft. Novell had done the work on the suit and assembled a very good legal team, but either management or the board where afraid to attack Microsoft head on in a suit. Novell had found some of the best attorneys in the industry that would take the case on consignment. To break the strangle hold on the OEMs, Caldera felt we needed to fight Microsoft in a court of law as well as build better products.

On the 10th of September in 1996, Caldera announced that they would release Digital Research’s CP/M, DR-DOS, PalmDOS, Multi-User DOS, and Novell DOS 7 in an open source form. The retail DOS package would be Caldera OpenDOS that would add networking capabilities to DR-DOS with NetWare and add “additional networking capabilities.” In the press release, Caldera also noted that they were considering the inclusion of a GUI as well as a web browser and TCP/IP stack. This was scheduled for Spring of 1997.

As of October in 1996, Caldera was selling Network Desktop for $99 (around $194 in 2023), the Caldera Internet Office suite for $329 (around $644 in 2023), the Caldera WordPerfect & Motif bundle for $250 (around $489 in 2023), and Caldera Wabi for Linux for $199 (around $389 in 2023). The Internet Office suite bundled WordPerfect, the NCD Z-mail client, the XESS NExS Spreadsheet, and Metrolink’s Motif libraries. The WordPerfect and Motif bundle was exactly what it is described as. Wabi (Windows ABI) was essentially a compatibility layer for Windows 3x, but this required the user to have a copy of Windows (unlike modern WINE).

Following on Caldera’s acquisition of LST and the parting with Red Hat, Caldera built their new Linux distribution upon LST. Wanting to make sure that they’d have quality software for this new system, Caldera supported the port of StarOffice 3.1 to Linux. This move was made when Caldera’s relationship with Corel (makers of WordPerfect which was featured in Network Desktop) soured. Unfortunately, while Caldera paid Star Division $350,000 (around $685000 in 2023) to port StarOffice to Linux for Caldera, Star Division was working on a new agreement with SuSE. This violated an exclusivity agreement between Caldera and Star Division. The two companies did eventually reach a settlement that pleased both parties, but this hurt Caldera in Germany where StarOffice was a leading office product and SuSE a leading Linux distribution.

On the 3rd of February in 1997, Caldera released OpenDOS 7.01. This was available free of charge for non-commercial and educational uses. This release offered multitasking, Novell Personal Netware (server and client), memory management via DPMS and DPMI, disk compression, and power management. The company also made public their plan to release the OpenDOS kernel source code in March.

The next Linux release from Caldera was Caldera Open Linux 1 in October of 1997. This was the first Linux distribution to ship with kernel 2.0 (using 2.0.25), and it included the Looking Glass desktop, the Netscape FastTrack web server, Netscape Communicator 4 and Navigator 3, StarOffice 4, Adabas D SQL database, and BRU 2000 backup utility among other commercial software applications. Still present was the LISA installation and administration utility, but it was now available in many languages. While this distribution was Slackware-based, it used RPMs instead of Slackware’s pkgtools. This release spanned three CD-ROMs. The first was the distribution proper, the second was labeled extra and included many of the proprietary software packages, and the third contained Adabas D. The first CD was now bootable, but floppies were still included for those systems that could not boot from CD-ROM. This release had more than one manual as well (three of them). There was a manual for the distribution and another just for Netscape FastTrack and yet another for StarOffice and other proprietary programs. This release was followed quickly by 1.1 at the end of the year. Version 1.2 was released on the 17th of April in 1998, and version 1.3 was released on the 28th of September in 1998 with kernel 2.0.35. Caldera Open Linux required an Intel 80386 or better CPU, 8MB of RAM (16MB recommended), 50MB to 500MB of HDD space (the default installation required 240), a VGA or better graphics card, and CD-ROM drive. Wabi, WordPerfect, Corel Draw, and other applications were offered for the system as well through Caldera.

Caldera’s lawsuit against Microsoft was hurting Caldera’s abilities to get OEM partnerships. Love claims that this was due to fear of retribution from Microsoft, and there is at least one instance of this certainly being true. Intel was talking to Caldera about a port of Linux to IA64, but this contract was given to VA Linux instead. The stated reason from the representative at Intel was that Microsoft had called the Intel executive team and Microsoft didn’t want Intel to work with Caldera.

Caldera was also struggling internally. Many in the company were losing faith in the company’s Linux initiatives and were desirous to shift focus to the embedded DOS market. The company had received investments from Ray Noorda at Canopy that totaled somewhere in the range of $16 million (somewhere around $31 million in 2023), and the company wasn’t turning a profit. Noorda, despite the financial situation, wanted to see the Linux endeavor continue. This strife led to the creation of two internal divisions at Caldera. Sparks led the DOS Division while Love led the Linux Division. The DOS Division had a bit more shine with more immediate profitability and the potential for cash from the lawsuit. The Linux Division was mostly a cost center. Then on the 2nd of September in 1998, the company officially split into three entities. Caldera Inc would continue with the lawsuit against Microsoft with Sparks as the CEO, Caldera Systems would continue with Open Linux with Love CEO, and Caldera Thin Clients would continue work in the embedded space with Roger Gross as CEO. Systems and Thin Clients were, however, wholly owned subsidiaries of Caldera Inc, and they were all now based in Orem, Utah.

For Caldera Systems, all of this could not have been more poorly timed. The Linux market was heating up with both SuSE and Red Hat quickly gaining market share.