The History of Commodore, Part 3

Are you keeping up with the Commodore?

This is part three of a series on Commodore. If you haven’t already, you may be interested in reading part 1, which covers the creation of the 6502, the founding of MOS and Commodore, and the circumstances that led to the creation of the first Commodore computers. Part 2 covers the Commodore VIC-20.

The newly combined entity of MOS and Commodore that constituted Commodore International had two successful computers in the PET and VIC-20. The IBM PC had been released not long ago, and Albert J. Charpentier, Bob Yannes, and Charles Winterble had been trying to produce state-of-the-art audio and video chips for what they called “the world’s next great video game.” Winterble was the head of engineering for Commodore, and Charpentier led the group at MOS who’d worked on the VIC. To build these chips and the game machine into which they’d go, Winterble stated that they examined the Mattel Intellivision, the TI 99/4A, and the Atari 800. They were trying to get as good a sense as possible for what people could do at the time, and thereby determine the required capabilities of their own machine. The team generally liked the sprites of the TI 99/4A, the collision detection and character mapped graphics of the Intellivision, and of course, they were fond of the VIC-20. The team knew the die size they’d have as well as the process they’d have, and these determined what could be fit on their chips. Charpentier was focused on graphics, and he had two draftsmen and a CAD operator working with him. Yannes was focused on audio and he had two draftsmen and a CAD operator working with him. Thanks to vertical integration, each individual circuit of each chip could be removed from the overall design and run as a test chip allowing the team an unusual amount of freedom in debugging. Toward the middle of November of 1981, after nine months, they’d completed their work with the resulting game console being named the Commodore MAX Machine or Ultimax depending upon the region. The two chips were the VIC-II (Video Integrated Circuit two) and the SID (Sound Interface Device).

The VIC-II featured 16K of address space and five official display modes. These modes were the standard character mode, multicolor character mode, standard bitmap mode, multicolor bitmap mode, and extended background color mode. These modes were all based off of a total limit of three hundred twenty by two hundred pixels and sixteen colors, or of forty by twenty five characters. It could handle eight sprites per scanline concurrently. The SID featured three voices which could be independently programmed, and four waveforms per voice (noise, pulse, sawtooth, triangle) with these having been capable of combination to produce more waveforms. The SID also handled game paddle or mouse input, external audio input, and random number generation.

In late November Charpentier, Yannes, and Winterble were in a meeting with Jack Tramiel, and Tramiel killed the game console plan with some urging to do so from all of those present at the meeting. This was a well timed move given the video game crash that was not too far in the future. He decided that these chips would instead go into a computer that shipped with 64K RAM, that would be low cost, that would be simple, and that would be introduced at CES in Las Vegas in January of 1982. Tramiel wanted a machine that did not yet exist to be ready for announcement and demonstration to the industry and public in around a month.

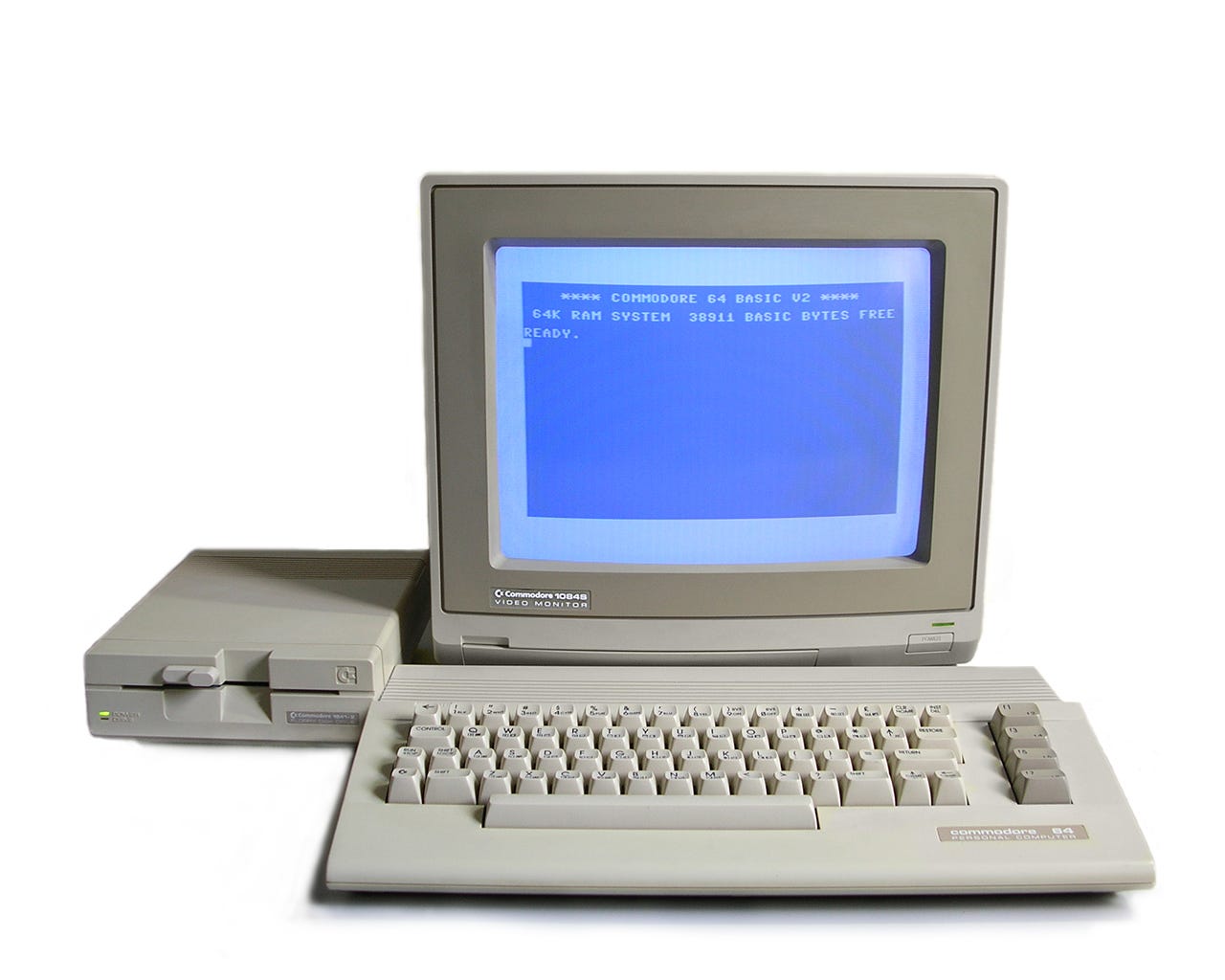

They’d already had a working machine, but a game console isn’t a general purpose computer. Two days of work led to a basic architecture being completed on paper. After that, Bob Russell, Bob Yannes, Shiraz Shivji, Yash Terakura, and David Ziembicki worked non-stop to get the project completed on time. The VIC-20’s KERNAL and BASIC were ported, the VIC-20’s case and keyboard were re-used, and the vertical integration of MOS/Commodore was leveraged to get affordable memory chips, as well as a revision of the 6502 CPU, the 6510, which featured an additional eight bit I/O port. Despite having many things pre-made for them, the team had to work through the holidays, and in the end, five machines were ready for CES. The machine was extremely well received at the event and volume production began almost immediately thereafter. Shipments of the new Commodore 64 started in August of 1982 with a starting price of $595 (around $1897 in 2023).

Beyond the improved graphics and crazily improved sound, the Commodore 64 increased the memory available to user programs to 52K. Expansion was available via cartridge, serial, cassette, and the user port. The user port is compatible with that of the VIC-20, and the VICMODEM was definitely still usable at the time. While the 64 has RF output, it also features composite video output (actually very similar to s-video) with separated luminance and chroma signals, and direct audio output. This meant that both the audio and video were significantly improved when used with one of Commodore’s monitors instead of a television. The C64 includes two controller ports on the right side instead of the just the one on the VIC-20.

The first units weren’t without their fair share of problems. Most of these were small, like a small bit of audio whine due to the video lines and audio lines being next to one another on the board and causing interference. This problem was solved with a board revision shortly after the initial market introduction. The most infamous issue was sparkle. This was an issue where small spots of light would appear on screen seemingly at random. This was caused by a voltage spike as the CPU and VIC-II alternated control of the system bus; a spike that was just wide enough that the ROM saw it as a valid address. It would then ignore the next address request and feed the wrong data to the VIC-II. This was a problem as the ROM contained the character set and the screen would then be littered with random pieces of characters. While this was corrected quickly with a few hundred thousand of the defective machines being sent out the door, customers took advantage of it. The price of the Commodore 64 dropped not too long after release. Some savvy folks would return their 64 for a full refund within the ninety day window, use the money to buy the machine more cheaply and pocket the price difference.

Aggressive marketing and pricing caused another problem of that nature for Commodore. In January of 1983, Commodore offered a $100 (around $309 in 2023) rebate in the USA for any customer who sent his/her old computer or game console to Commodore after purchase. The Timex Sinclair 1000 was sold by some mail-order companies for as little as $10. This meant that a savvy customer could purchase a TS1000 and send it to Commodore for $100. Later in the year, the TI 99/4A joined the TS1000 in this use case as its price was dropped to just $49 (around $151 in 2023) after Texas Instruments announced its intention to exit the market. This last must have been sweet revenge for Tramiel. TI had almost cost him his company when they entered the calculator market and now Commodore had cost TI the computer market.

Spring of 1983 was rather tumultuous for Commodore’s staff. Charpentier, Yannes, Winterble, Ziembicki, and Bruce Crockett (Crockett was largely responsible for all of the debugging work) left Commodore and started Peripheral VIsions, which was later renamed to Ensoniq. Shortly after that, Winterble left Ensoniq to become the VP of Electronics at Coleco.

By June, the price of the Commodore 64 had fallen to $299 (around $924 in 2023). Like the VIC-20 before it, it was sold absolutely everywhere. This combination brought strong sales, which in turn brought more developers to the platform. The ports of Atari 8 bit titles to the 64 started to pour into the market. The advertising campaigns were also insane and featured quite the ear worm.

In July, Stan Wszola at BYTE wrote a review of the 64. In particular, he praised the machine for its good sound noting the rarity of this feature, and he praised the User’s Guide, and the optional Programmer’s Reference Guide. His main complaint about both manuals was the lack of in-depth information on disk drives. His main complaint overall was the lack of quality control at Commodore. Yet, his review is reflective of many prevailing sentiments of the time, or at least those that were written down and therefore available to me today:

The Commodore 64 is a good introductory machine. It has something for almost every type of user. Its range of features make it equally suitable for me and my 5-year-old daughter to use. The color and graphics make games and educational software interesting enough to hold a child’s attention, yet it has enough sophisticated features to allow me to do productive work such as word processing and home finances. With the right price, plenty of available software, and numerous desirable features, the Commodore 64 is an impressive machine.

By the end of 1983, the home computer had become popular enough that the New York Times declared Christmas of 1983 the one which would see computers find a place under the Christmas tree. The article spends some time talking about struggles at Coleco, and that this struggle directly benefited Commodore. Commodore had dropped the price of the 64 to $200 (around $618 in 2023), and Coleco’s strategy of selling the Adam with a tape drive and printer for $600 (around $1854 in 2023) while an amazing deal was hurt by production delays.

By the close of the year, Tramiel’s decision to lower the price of the Commodore 64 lost him his job. He and Commodore chairman Irving Gould got into a rather explosive fight after which Tramiel was out. He then went on to purchase Atari’s computer division from Warner Communications. Yet, no matter what the board may have thought of Tramiel’s decisions, the Commodore 64 was getting new titles made just for it, more than half a million Commodore 64s had been sold just through that Christmas season, and the Commodore 64 was the only home computer that was both widely available and not discontinued. Revenues for 1983 were over one billion and income was over one hundred million.

Two variants of the Commodore 64 were made available in 1983, the Educator 64 and the SX-64. The Educator 64 was a Commodore 64 in a PET style case with a green phosphor display. The SX-64 was a luggable version featuring the first full-color display in a portable computer. The screen was five inches, and the unit sported an integrated 1541 disk drive but lacked the cassette port.

By 1984, most of the quality and reliability issues of the 64 had been addressed. In the USA and Canada, floppy disks had also become far more popular displacing both cartridges and cassettes. Video game makers were heavily focused on the Commodore 64 with Sierra and Broderbund being the two holdouts. Sierra was focused on the IBM and the Apple II, and Broderbund was mostly focused on the Apple II. In Europe, things weren’t quite as settled. Those markets were largely taken by the ZX Spectrum, the BBC Micro, and the Amstrad CPC with the 64 definitely being present, but not dominant.

In 1985, Commodore released the 128 designed by Bil Herd with assistance from Dave Haynie, Frank Palaia, and Dave DiOrio. The software work was done primary by Fred Bowen, Terry Ryan, and Von Ertwine. The 128 was introduced at CES just like its predecessors. It was largely compatible with the 64, but featured two banks of 64K memory bringing the total to 128 as the name would imply. It also featured eighty columns of text, a redesigned case and keyboard, a Zilog Z80 for compatibility with CP/M, an 8502 main CPU, and an updated version of BASIC.

Despite the 128 being a far more capable and far more complex machine than its predecessor, it was compatible with two other platforms. This did help it sell, but it also hurt the machine considerably. Very little native software was written for the 128. A software maker could simply target the Commodore 64 or CP/M, and they’d then have also reached the 128. The 128 was also more expensive at $299 (about $855 in 2023) while the 64’s price had dropped to just $149 (around $426 in 2023).

With the 128 never quite living up to the hopes of Commodore, the company released the 64C. This was essentially a 64 remodeled to more closely resemble the 128, and the chip packaging and manufacturing processes were more advanced allowing an overall chip count reduction.

In hopes of battling Nintendo and SEGA, Commodore released the Commodore 64 Games System. This was a Commodore 64 with no keyboard, most external expansion and connectivity removed, vertically inserted game cartridges, and no BASIC in ROM. It was a commercial failure. In part this failure was simply due to the competition, but it was also due to floppy disks having become the primary software distribution media for the 64. The majority of titles simply could not be loaded on the 64 Games System.

The Commodore 64 was the most popular computer of the 1980s, and until the release of the Raspberry Pi, was the single best selling computer of all time with twelve and half million (possibly as many as seventeen million) units having been sold. The last software title sold for the machine by a major software house in North America was Ultima VI in 1991, the bookend of a software library comprised of roughly ten thousand titles. The 64 survived both the video game crash and the home microcomputer price war managing to become the single most popular computer of its day. It was a computer for the masses and not for the classes. It was a machine from West Chester in Pennsylvania and not from Silicon Valley. As the rust belt was struggling and in general economic decline, the Commodore 64 was seeing its final days. Unseating the Commodore 64 was accomplished by three separate forces. First, the video game market was taken by Nintendo and SEGA. Second, IBM PC compatibles took the computer market as their prices fell. Third, the Commodore 64 was an eight bit computer when by the 1990s thirty two bit machines were common.

I now have readers from many of the companies whose history I cover, and many of you were present for time periods I cover. A few of you are mentioned by name in my articles. All corrections to the record are welcome; feel free to leave a comment.