The History of Xerox

A Monochromatic Star

On the 18th of April in 1906, a Wednesday, a small company was started in Rochester, New York that made paper for photography. The Haloid Company wasn’t alone in this, not even in its own area, being neighbors with Eastman Kodak. Having been founded by a group of men led by George C. Seager, the company did well, but its success was modest. In 1912, Gilbert E. Mosher bought a controlling interest in the company for $50,000 which would be about $1.7 million in 2025 dollars. Mosher then became president of the young company and promptly directed Haloid to develop new and better papers. While this product was under development, the company opened sales offices in Chicago, Boston, and New York City under the direction of Joseph R. Wilson, VP of sales. The new paper product, the Haloid Record, was released in 1933, and it was successful.

The company’s sales, despite the Depression, hit nearly $1 million by the end of 1934. Wilson then moved to buy the Rectigraph Company in 1935. Rectigraph made a photocopier that used Haloid’s paper, and this would allow the company a bit of vertical integration. Great idea, but the company needed funds. Haloid went public in 1936 to finance the acquisition.

On the 8th of March in 1938, Mosher became chairman of the board. Joseph R. Wilson, who’d led the company’s various expansion efforts, became president.

A quick detour

Chester Floyd Carlson was working for Bell Labs in New York City in 1934 as a patent clerk. He was 28, a physicist with a degree from CalTech, making little money, and had a job that didn’t exactly satisfy him. He’d recently clawed his way out of debt, which gave him some drive, but each day was a grind. He was nearsighted, so he was always bent over his desk to read the papers his job required, and therefore frequently felt pain in his back and neck. Further, he was constantly manually copying patent applications onto carbon paper.

Carbon paper is thin and its coated with wax and pigment. This paper is then put between two sheets of ordinary paper to make a copy of whatever is typed on a typewriter. Alternatives were available such as the mimeograph where a stencil was made on a typewriter, the stencil was then clamped to a cylinder, and as the cylinder turned to pull sheets of paper through, ink was fed onto the stencil leaving a copy of the text on each sheet. This was often messy, error prone, and the mimeograph fluid had a foul odor. The next method for copying was to use a rectigraph or photostat. These took photos of a document, then developed them with the usual photo development processes, differing from normal photography in the paper used and the automation employed. Another wet copy method was offset printing which made high quality copies but involved the creation of a paper master that was transferred to a metal plate and essentially stamped onto sheets. All of these were labor and time intensive while being messy and ill-suited to the type of work Carlson was doing.

In late 1934, Carlson was laid off. He took a job with a patent attorney, got married, and then found a job a year later with P. R. Mallory. All of these various pressures, plus a clear market need, pushed Carlson to work at making a clean, fast, reliable, and high quality copier. As he put himself:

I had my job, but I didn’t think I was getting ahead very fast. I was just living from hand to mouth, you might say, and I had just got married. It was kind of a hard struggle. So I thought the possibility of making an invention might kill two birds with one stone: it would be a change to do the world some good and also a chance to do myself some good.

Carlson chose to anger his new bride, Elsa, and used their kitchen as his first laboratory. After a particularly bad accident spilling sulfur on the stove, Elsa made him move his lab elsewhere. His mother in law owned a building and gave him a room above a tavern in Queens. Of course, experimentation costs money and doesn’t make money, so Carlson was taking courses at New York Law School in the evening to become a patent attorney. To speed up his work, especially as Carlson was now suffering arthritis in his spine, he hired Otto Kornei.

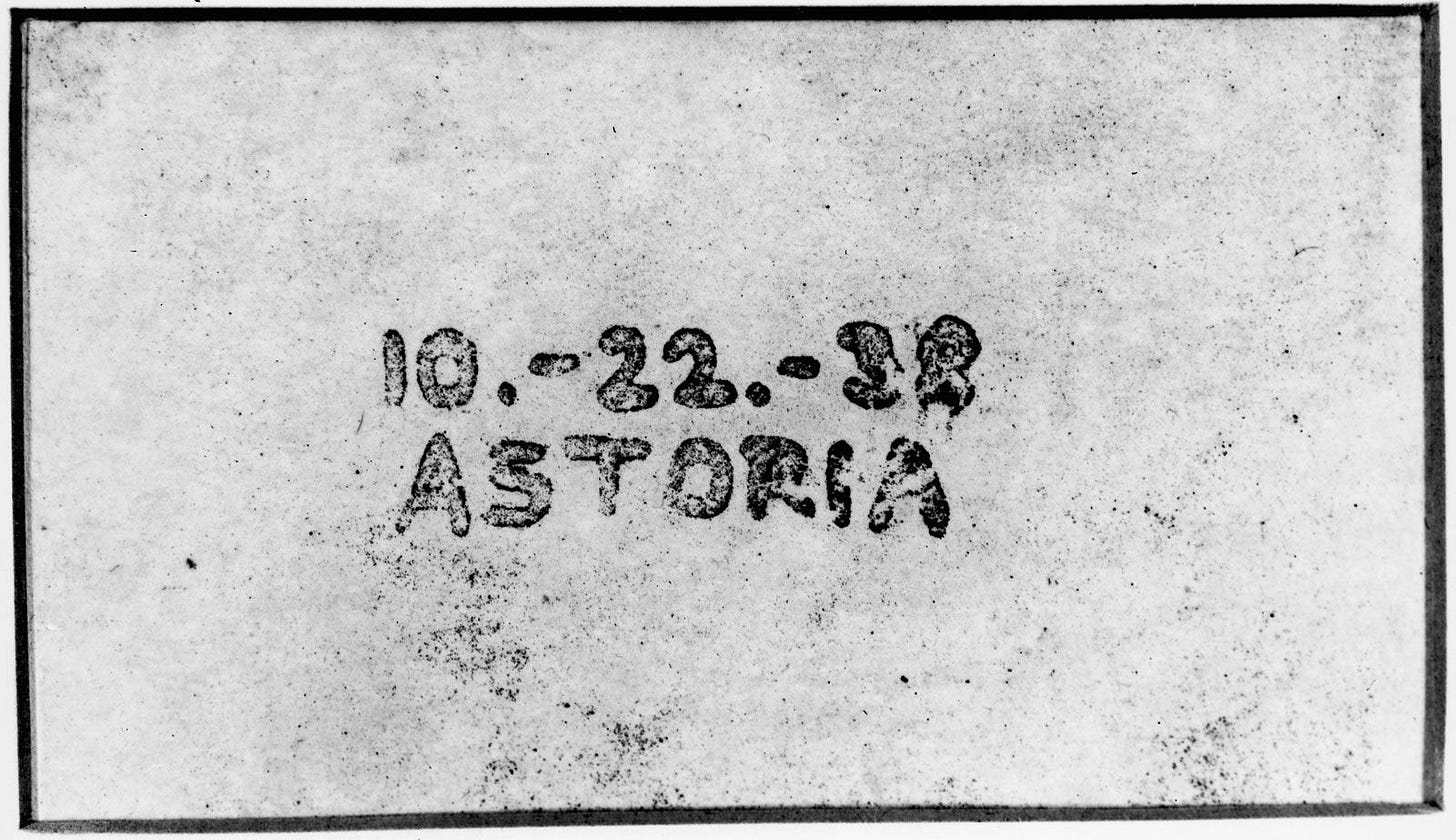

On the 22nd of October in 1938 (this article is late, you see), Carlson and Kornei succeeded. They’d put sulfur on a zinc plate and rubbed the sulfur surface with a handkerchief to build an electrostatic charge. They had a glass slide with India ink on it that read “10-22-38 ASTORIA” and they put the slide on the sulfur surface. With a few seconds of exposure, the primary part of the experiment was complete. They then removed the slide, sprinkled lycopodium powder on the surface, and blew on the sulfur. The excess powder gone, they saw the duplication. They’d invented electrophotography.

Carlson proceeded to attempt to license his patent (2,221,776) to over twenty companies including IBM, Remington Rand, RCA, and GE, and all of them said no. It certainly didn’t help that World War II was underway, and anything not directly involved in the war effort was given little attention. His wife, disapproving of his effort with little to show for it, chose to divorce him.

Still, other things were going well. Carlson had earned his law degree and had become head of the patent department at P. R. Mallory. This put him in a good position when Russell Dayton of the Battelle Memorial Institute dropped by in 1944. The two got to talking and Battelle funded his research and development.

Back to Haloid

While the company had gone public and raised money, the company’s employees went on strike. Wilson stepped in to resolve the dispute, but things were rocky until the war. World War II was great for the company, and they made quite a bit selling photo paper to the military for reconnaissance purposes. Then, of course, the war ended. Every company that had done well selling to the military was faced with a ton of supply, little demand, and fierce competition. Mosher wanted to the sell the company, but Wilson didn’t. Wilson was the son of one of the founders, and he had a son of his own working in the company. For him, Haloid was much more than just a paper company. Wilson won.

In 1945, Haloid’s head of research, John Dessauer, found out about electrophotography and brought it to the attention of Joseph Chamberlain Wilson, the son of Joseph R. Wilson. The younger Wilson immediately saw the value in it, and he and Dessauer went on a trip to Columbus, Ohio to see it. In 1946, Joseph R. Wilson’s son, Joseph Chamberlain Wilson, became president of Haloid. On the 2nd of January in 1947, Haloid and Battelle signed a royalty agreement on the electrophotographic process.

While working to commercialize the technology, a professor at Ohio State University suggested a name change of the process to a combination of xeros and graphein, xerography. Yet, making xerography into a product would cost Haloid $75 million between 1947 and 1960. They borrowed, they sold stock, and Wilson ceased taking a salary and took only shares. Several executives mortgaged their homes to continue funding the project. Carlson himself even moved to Rochester to aid in product development, but he never took a salary from Haloid. Instead, in 1955, Haloid bought his patents in exchange for 50,000 shares of Haloid.

Of course, Haloid did release products using the technology; they just weren’t great. The Model A, nicknamed the OxBox, was a manually operated machine requiring 39 steps and around three minutes to make a single copy. The Model A was followed by the Foto-Flo Model C, Xerox Lith-Master, and CopyFlo among others. None of these did well, but the company was fully invested in the technology. They changed their name to Haloid Xerox in 1958.

The process changed over time. The sulfur was replaced with selenium. Corona wire then applied a uniform electrostatic charge to the plate. The ink became a toner made of iron, ammonium chloride, and plastic. Brushes made from the hair of Australian rabbits were rotated in the machine to remove excess toner, and small air nozzles blew sheets of paper through the machine. All of these advancements were brought together in the Xerox Model 914. The product was introduced on the 16th of September in 1959 at the Sherry-Netherland Hotel in NYC. While one of the two units caught fire, the other worked without error. For the first time, a person could have copies made automatically onto plain paper without any mess (provided the copier didn’t burn the building down).

By this point, the company couldn’t afford a large advertising campaign, but they placed some ads in magazines read by business professionals and ran a few television ads. Other moves by Peter McColough’s marketing team were far more clever. The company placed machines in well-traveled public spaces where it was on display, and in addition to sales, they also offered machine rental for smaller organizations. This was a low price for up to 2000 copies, and each copy after was 4¢. They also promised that a machine could be returned within fifteen days. The 650 pound behemoth was wildly successful. The company changed its name to Xerox in 1961, and began trading on the NYSE as XRX the same year. After a lifetime of struggle and poverty, Chester Carlson was worth more than $200 million. A year before he passed, he gave away more than $150 million spread among the NAACP, the Rochester Zen Center, Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo-ji, the University of Virginia, the New York Civil Liberties Union, and the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions.

Xerox’s crossed $1 billion in revenue in 1968, and Charles Peter Philip Paul McColough became the CEO of Xerox. Wilson was still the chairman, and he’d feared the development of computers would render the text-to-paper/image-to-paper business of Xerox would be rendered obsolete. He’d said to McColough previously: “if we’re going to be big ten or twenty years out, we’ve got to be able to handle information in digital form as well as graphic form.” Wilson was successful in impressing the need on McColough, and McColough felt that Xerox should develop the architecture of the Information Age. To this end, in May of the following year, Xerox bought Scientific Data Systems, a maker of mainframe computers, for $918 million in stock. This brought SDS’s founder, Max Palevsky, onto Xerox’s board as well as Arthur Rock. SDS had never exceeded $10 million in a single year, yet Palevsky became Xerox’s single largest shareholder. In July, Jacob E. Goldman (Jack), chief scientist, went to McColough and said “Look, now that we’re in this digital computer business, we better damned well have a research laboratory.” His proposal went over well as the executive staff all wanted Xerox ranked alongside IBM and AT&T who had the quite famous research centers of Yorktown Heights and Bell Labs. What Goldman saw was one step further than Wilson. He realized that software would lead hardware as the driver of innovation, and that Xerox could profit from the ability of a computer to drive a printer. He envisioned a machine that was half computer and half xerographic printer. The Palo Alto Research Center was the second research center at Xerox, and it was three thousand miles away from Rochester. While this distance helped in giving PARC freedom, it also helped in divorcing the center from the needs of Xerox.

PARC began operation on the 1st of July in 1970. Goldman then chose George Pake to be PARC’s first director, and he split PARC into three units: the Systems Science Laboratory (SSL) under Bill Gunning, the Computer Science Laboratory (CSL), and the General Science Laboratory (GSL) under Pake himself. Pake, in turn, chose Robert Taylor, former deputy director of ARPA’s information processing techniques office who’d shepherded the creation of ARPANET, to run the CSL until someone else could be found. Taylor was exactly the sort of man to recruit the best minds, and he did so. The initial projects included SSL developing laser printing, optical memories (eventually leading to CD-ROM), and speech recognition. The CSL was working toward graphics and a computer system for the research center, and the GSL was working on solid-state technologies.

Early in its life, the fate of PARC was precarious. Xerox had missed its profit targets for both November and December of 1970. The executive staff was now mostly comprised of accountants and financial engineers, and they wanted to control spending. The proposition to kill PARC was put forward. John Bardeen, who’d worked with Brattain and Shockley inventing the transistor, had worked as a consultant for Xerox starting in 1951, and he’d joined the board of directors sometime later. His voice carried weight. At the suggestion to kill PARC, he stated: “this is the most promising thing you’ve got. Keep it!” So, PARC lived.

Taylor had the idea of taking Douglas Engelbart’s oNLine System and moving further with it. He’d helped secure funding for ARC, and he still had contacts at SRI. As people at ARC began looking to leave, it was William K. English, better known as Bill English, who was first to join PARC (he later worked at Sun). English then recruited another twelve engineers from ARC. Taylor’s prior work had also acquainted him with the Berkeley Computer Corporation, and the Berkeley 500. He had purchased the machine for ARPA and shipped it to the University of Hawaii allowing the school to join the ARPANET. That machine’s hardware design was largely the work of Chuck Thacker, and its software the work of Butler Lampson. Both men were recruited as were some of the folks who’d worked with them: Peter Deutsch, Ed Fiala, Richard Shoup, Charles Simonyi (later wrote Multi-Tool Word for Xenix, which became Word). He also hired Alan Kay from SRI. While Kay hadn’t worked on NLS, he’d been present at the demo, and regarded it as one of the greatest experiences of his life. His master’s thesis at the University of Utah in June of 1968 was titled “FLEX: A Flexible Extendable Language” which envisioned a hardware and software system designed for each other. The language wouldn’t be too unfamiliar to us today, but about the hardware, he lamented that nothing existed to fulfill his dream. He wanted a computer with “enough power to out-race your senses of sight and hearing, enough capacity to store thousands of pages, poems, letters, recipes, records, drawings, animations, musical scores, and anything else you would like to remember and change.” Conversations with Kay have been described as a ramble through ideaspace. Years later Kay would better articulate what was running through his head:

Computers’ use of symbols, like the use of symbols in language and mathematics, is sufficiently disconnected from the real world to enable them to create splendid nonsense. Although the hardware of the computer is subject to natural laws (electrons can move through the circuits only in certain physically defined ways), the range of simulations the computer can perform is bounded only by the limits of human imagination. In a computer, spacecraft can be made to travel faster than the speed of light, time to travel in reverse.

Yet, at this time, his vision was absolutely, truly, ahead of everyone around him. During his interview for PARC, he was asked what he thought his greatest achievement would be at the center, and he replied a personal computer. This wasn’t a term at the time, so the interviewer asked, what’s that? He grabbed a nearby notebook, held it up and said, “this will be a flat panel display, there’ll be a keyboard here on the bottom, and enough power to store your mail, files, music, artwork, and books; all in a package about this size and weighing a couple of pounds. That’s what I’m talking about.”

The CSL, like the other two groups, had rented chairs, rented desks, a telephone, and not much else. Of course, to do research on computers, they’d need a computer, and the computer they wanted was DEC PDP-10. At this point, Paul Strassman was replacing every IBM and DEC machine at Xerox with an SDS machine. CSL was brave enough to make the request for DEC, but the request was denied. There was a ton of back and forth, many bridges burnt, and quite a bit of mudslinging, but it boiled down to a denied request. Given this situation, the CSL built the MAXC (Multiple Access Xerox Computer [the C is silent, the name is joke about Max Palevsky]) which emulated the PDP-10. Quite a bit of discrete logic was implemented in microcode, and MAXC used dynamic RAMs rather than core. Those RAMs were 1103s from Intel, and PARC ordered a ton of them. MAXC had 25000 Intel 1103s arranged as 96 on each of 256 boards, with spare completed boards on hand. Many of the chips didn’t work, and this led to PARC’s first creation, a memory tester, a later version of which was used by Intel itself to test RAM chips on the production line. It also led to the implementation of error correction for RAM. In the end, their system ran TENEX, and it was faster than the PDP-10 whose software it was designed to run. It was also quite capable at limited amounts of multitasking, had more accurate floating point (though to run Lisp they actually added the errors back in as Interlisp expected them), and was more reliable. MAXC set the record for uninterrupted availability on the ARPANET, which is amazing for a machine designed and built in about eighteen months for $750k.

Two aspects of building MAXC became extremely important for later work at PARC’s CSL. First, it created a culture of building hardware and software in-house. Second, it established relationships with vendors in the area. Then, this early culture led to a rule: never create a system that isn’t engineered for a hundred users. Timesharing computers? Expect a hundred simultaneous users. Programming languages? A hundred programmers should all be able to easily get going. Personal computers? Expect a hundred novices to be able to sit down and easily get going. Everything had to work at scale, and most importantly, everything had to actually work. During this time period, the CSL also adopted a hiring process. All new recruits were subject to serial interviews with the entire staff, and anyone hired was required to win approval by unanimous, if not entirely enthusiastic, consent.

After the completion of MAXC, Taylor had to hire the actual director of the CSL. I can’t imagine that it’s easy to recruit a person to come be your own boss, but Taylor did. The man he chose, and then all of CSL chose, was Jerome I. Elkind from MIT and BBN. Elkind then recruited some of his own people from BBN chief among whom were Lisp programmers Daniel Bobrow and Warren Teitelman.

Xerox had folks constantly looking at the technology landscape and analyzing everything that may, at some point, be a threat to Xerox’s business model. They wanted to know what the future would be. At the same time, they viewed PARC as insolent due to the PDP-10 issue and the attitudes of people at PARC during the dispute. A major force in this was Don Pendery. The view of Pendery and many at Xerox was one of defending against the future, while PARC’s view, as Alan Kay put it, was “the best way to predict the future is to invent it!” The problem is, corporations really don’t work that way. A corporation needs measurable plans, on paper, that can be presented in a boardroom. In answer to Pendery, George Pake sent the PARC Papers for Pendery and Planning Purposes, thereafter referred to as the Pendery Papers, to Xerox corporate offices. This report is among the most accurate descriptions of the future produced. It described the use of dense magnetic tape for archival and described something like VHS tape, tablet computers with a decently high resolution displays (1024 by 1024 pixels) and wireless networking, voice recognition, widespread use of scanners with OCR, optical storage media, and the networked paperless office. While this was sent to Xerox as a report of what was to come, PARC could also have just said it was what they intended to build.

More than anyone else at PARC, or maybe just more outspoken about it, Alan Kay wanted to build something like what Engelbart and Bush had envisioned. For him, this was his tablet, the Dynabook. The issue was, the development of all of the hardware necessary to make the Dynabook a reality would take a considerable amount of time. He needed an interim device that could do most of what he wanted. Knowing this, Lampson asked Kay if he’d like Lampson, Thacker, and Ed McCreight (McCreight had worked with Rudolf Bayer to invent B-trees) to build him such an interim computer. Kay answered in the affirmative, and on the 22nd of November in 1972, Thacker and McCreight began building the interim Dynabook.

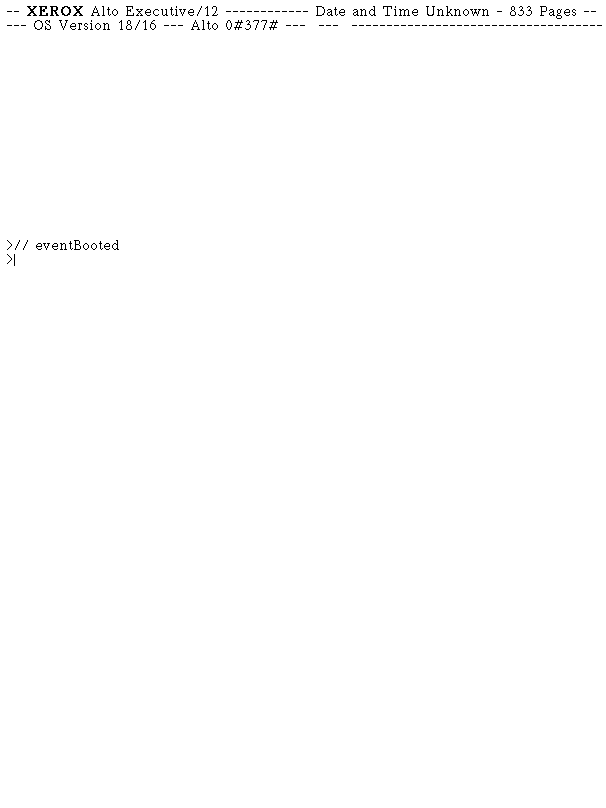

While I have said that Kay really wanted this, that’s not the complete truth. Lampson wanted a cheap PDP-10, Thacker wanted something faster than a DG Nova 800, and Kay wanted his Dynabook. This machine was the Xerox Alto, and it was working by the 1st of April in 1973.

The Alto had a 606 by 808 pixel, monochrome, bit-mapped display, a three button mouse, a five-key chord set, 2.5MB removable HDD, 16-bit highly microcoded CPU built from TTL, 128K RAM (really 64K 16bit words) expandable to 512K when using banking, and it was about the size of an under-counter fridge. And on the 1st of April, it simply booted to a screen that read “Alto lives.” The key was, PARC now had machines that could be built cheaply, and all of these cheap machines were combined with a screen and a pointing device. The display, keyset, and mouse were clearly ideas from NLS, but the keyset never became popular, and the mouse was refined. First, the buttons were nicer, and second, it used a ball rather than wheels.

Everyone at PARC’s CSL was aware of Alohanet (packet radio network at University of Hawaii), and around this time, Thacker was thinking about connecting machines with coaxial cable. He made the statement that coaxial cable is nothing but captive ether, and he proceeded to work on it. Robert Metcalfe (later founder of 3com) and David Boggs then worked on it for a year, and ethernet began to connect Altos at PARC. Some have commented that Alohanet wasn’t the most important part, but rather that Boggs having been a ham radio operator was. He was quite familiar with coercing unreliable things to reliably communicate. Either way, the networked paperless office was being built.

I’ve already mentioned that early DRAMs were unreliable, and this network allowed another issue to be solved. When any Alto was idle, it ran a memory check. Upon the failure of any chip, the Alto would send an alert over the network stating which Alto was faulty, which RAM slot held the bad chip, and which chip in particular was failing. You could be sitting at your desk working while completely unaware anything was broken only to have a repairman show up and state that he needed to service your machine.

Gary Starkweather over in the Webster, NY research center was working on laser printers. The VP of the Business Products Group for Advanced Development, George White, called Goldman to have Starkweather transferred to PARC. Pake was thrilled, and Starkweather moved into the Optical Science Lab (originally part of the SSL). The first laser printer was called EARS for Ethernet Alto Research character generator-Scanning laser output terminal. It was built by Starkweather and Ron Rider. In 1973, it printed documents created on an Alto sent to the printer via ethernet.

Of course, when thinking of the Alto, most people think of the GUI. This wasn’t quite a thing on day one. Initially, the Alto was text oriented.

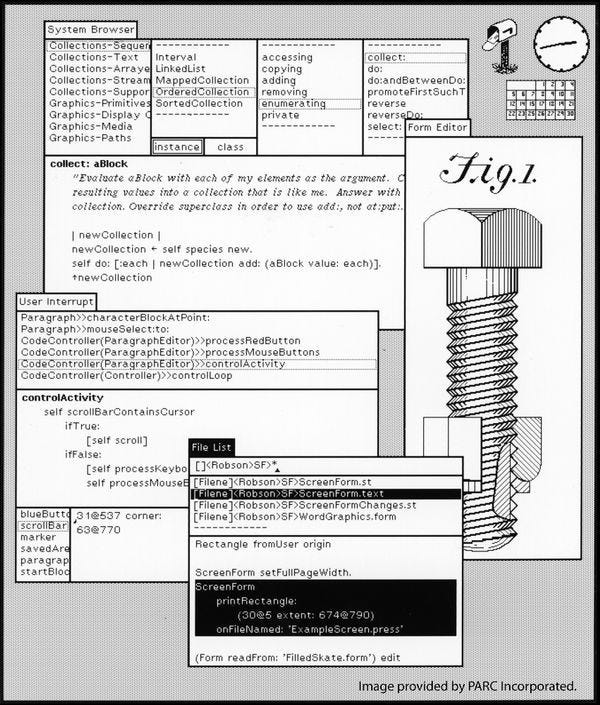

Of course, this didn’t remain the case. By the time people outside of PARC saw an Alto, it was a GUI oriented machine. If one were to use SmallTalk, the interface was superficially similar to the later Plan9 Rio, and the language was object-oriented and made use of message passing.

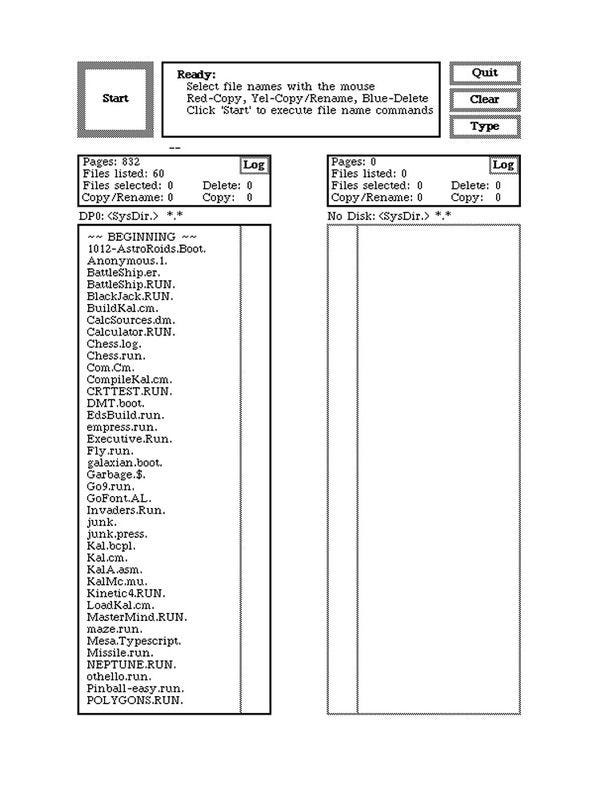

There were the WYSIWYG text editors Bravo and Gypsy, Laurel and Hardy email clients, Sil vector graphics editor, Markup paint program, Draw graphics editor (lines and splines), the WYSIWYG circuit editor ICARUS, multiplayer networked gaming, the tiled-window Cedar development environment complete with a strongly typed language (called Mesa) and desktop icons and image viewers, and the Alto had a semi-graphical file manager called Neptune.

The Alto was the first machine to give users a truly simple point-and-click, cut-and-paste, WYSIWYG, WIMP (windows, icons, menus, pointer) environment. It was also the first system to bring together networked workstations with email, ethernet, and printing. The main tools we know today that were missing were spreadsheets and databases.

As great as the Alto and its software were, Xerox didn’t bring them to market. PARC presented the Alto, ethernet, laser printers, word processors (even one in Japanese), and so on, but there was no development organization at Xerox dedicated to taking research prototypes to market. When there finally was in 1976, there still wasn’t a formalized method for transferring technology within the company (that would take another year). Then, as mentioned previously, there was the disfunction between PARC and Xerox corporate that likely made working together impossible anyway.

Adele Goldberg was a researcher within the Smalltalk Group and conceived of a portable workstation. It conceptually borrowed from the Dynabook, but it was a far more realizable goal for the 1970s. A workable and usable prototype was completed in 1978, and around ten were built. The machine was designed around an Intel 8086 running at 1MHz, 256K RAM, a 320K floppy disk drive, and a seven inch, 640 by 480 pixel, monochrome display. It had a mouse, keyboard, 300 baud modem, ethernet, two channel DAC, an EIA-422 interface, and an IEEE 488 interface. The machine could be powered by battery or a wall socket and weighed in at 48 pounds.

Lynn Conway had joined PARC in 1973 already having accomplished quite a bit at IBM in the realm of superscalar design. Far more important than the Alto’s GUI was what the system enabled. Using the graphical environment, the network, and the laser printer, Conway was able to build ICARUS with the help of Carver Mead, Doug Fairbairn, Jim Rowson, and Dave Johannsen. Conway conceived of designing systems using large structured and functional blocks rather than individual transistors or gates. The structures were purposefully designed to be put together in ways that would eliminate wiring delays. Effectively, Conway and Mead had invented the first EDA tool the way we think of them today (the very first having been at IBM in 1966). In June of 1977, Conway then began working on a book using the Alto’s desktop publishing software. This work combined the ideas of Mead and Conway, included an ICARUS tutorial written by Fairbairn and Rowson, and included design examples made by Johannsen. The book was titled Introduction to VLSI Systems. The first classes to use portions of the book were held in 1978 by Conway as a visiting professor at MIT, the book was published in 1979, and it became the standard text for education in the field. It was then translated into Japanese, Italian, French, and Russian, and was being used in around 120 universities around the globe. Fairbairn went on to cofound VLSI Technology with his company obviously using the technology. Jim Clark learned the VLSI design system from Conway while spending a summer at Park, and went on to design the Geometry Engine and found Silicon Graphics. Of course, as Conway went off to MIT, the Alto made it out of PARC. Altogether, around fifty Altos were donated to MIT, Stanford, and Carnegie-Mellon. The machines were put to work in the research communities of those schools, often in AI work, and they were certainly used for VLSI design courses. Conway left PARC for DARPA’s Strategic Computing Initiative in 1983.

In the autumn of 1979, Jef Raskin and Bill Atkinson had been working on the Lisa at Apple for about a year, and they had been urging Ken Rothmuller, the project manager, to use a bitmapped screen. The Lisa had working graphics from an early point in its development thanks to Atkinson’s prior work on the Apple II Pascal’s graphics. LisaGraf, which would later become QuickDraw, had been created by the spring of 1979, and a basic user interface existed shortly later. The teams at Apple were well aware of PARC. Atkinson had learned of SmallTalk as an undergrad, Raskin had worked at PARC, a few Apple employees had friends working there, and some people at Apple had worked for Engelbart at SRI. The real problem for these teams was in convincing leadership at the company of the value of these technologies. Unbeknownst to most staff was that earlier that year, Xerox had invested $1 million for 100,000 pre-IPO share of Apple. In exchange for this, Apple wanted access to PARC. Raskin arranged two visits, and Apple’s engineers were treated to all of PARC’s various innovations. These weren’t simple demonstrations, but rather full walkthroughs of the technologies, how they worked, and how they integrated together to build a networked office. Bill Atkinson and Andy Hertzfeld themselves aren’t too sure on the chronology, but Hertzfeld believes that Apple had a mouse-oriented windowing system before the PARC visit. We do know, for sure, that such a system existed by the spring of 1980, and further that all vestiges of a soft-key based user interface were gone by that summer. Steve Jobs was on the second visit in December, and of the visit itself, Steve Jobs later stated:

I had three or four people (at Apple) who kept bugging that I get my rear over to Xerox PARC and see what they are doing. And, so I finally did. I went over there. And they were very kind. They showed me what they are working on. And they showed me really three things. But I was so blinded by the first one that I didn’t even really see the other two. One of the things they showed me was object oriented programming – they showed me that but I didn’t even see that. The other one they showed me was a networked computer system… they had over a hundred Alto computers all networked using email etc., etc., I didn’t even see that. I was so blinded by the first thing they showed me, which was the graphical user interface. I thought it was the best thing I’d ever seen in my life. Now remember it was very flawed. What we saw was incomplete, they’d done a bunch of things wrong. But we didn’t know that at the time but still thought they had the germ of the idea was there and they’d done it very well. And within – you know – ten minutes it was obvious to me that all computers would work like this some day. It was obvious. You could argue about how many years it would take. You could argue about who the winners and losers might be. You could’t argue about the inevitability, it was so obvious.

The goal of all of that urging was accomplished. Apple executives too became believers in a graphically oriented future. They built upon and refined these ideas creating something totally new, quite elegant, and with Macintosh, quite successful. At least one person at PARC knew that giving people such access wasn’t the best idea. Adele Goldberg argued vociferously against allowing Apple in a meeting over the course of three hours. She later stated:

He (Steve Jobs) came back and I almost said asked, but the truth is, demanded that his entire programming team get a demo of the Smalltalk System and the then head of the science centre asked me to give the demo because Steve specifically asked for me to give the demo and I said no way. I had a big argument with these Xerox executives telling them that they were about to give away the kitchen sink, and I said that I would only do it if I were ordered to do it, cause then of course, it would be their responsibility, and that’s what they did.

On the other hand, Larry Tesler was delighted by Apple. He said that the Apple team more well understood the technology and what it meant than anyone among Xerox’s leadership in just an hour. Tesler joined Apple in 1980.

Naturally, the whole matter of the GUI became quite litigious. Early on in the life of the Macintosh, Apple needed software developers. The company gained a friend with Microsoft to whom they licensed many of their GUI technologies. Apple didn’t seem to care when Microsoft released Windows 1.0, but they certainly cared when Microsoft released Windows 2.0. On the 17th of March in 1988, Apple filed suit against Microsoft and Hewlett-Packard in San Francisco over the look and feel of the Macintosh. On the 25th of July in 1989, Judge William Schwarzer stated that of the 189 features Apple claimed Microsoft to have copied, all but ten were covered by the license Apple had granted. Then on the 14th of April in 1992, Judge Vaughn Walker ruled those remaining ten elements uncopyrightable. When this finally ended in 1994, the courts were in favor of Microsoft due to prior art on the overall concepts and due to the license having been granted.

IBM’s first copier had been released in April of 1970, and it wasn’t a good product. It did, however, have the name of IBM behind it. Xerox quickly chose to sue IBM for patent infringement and this was settled in 1978 with IBM having paid Xerox $25 million. Unfortunately, Xerox was then under fire from the FTC, Kodak began competing with them, Canon entered the market, and Ricoh entered the market. Whether Xerox simply knew it was potentially dangerous, or because they wanted to stay ahead of competitors, Xerox purchased Kurzweil Computer Products in 1980 from Ray Kurzweil. Kurzweil’s company had developed a product that combined omni-font OCR, CCD flatbed scanning, and a text-to-speech synthesizer as the Reading Machine allowing the blind to easily consume textual information. This company became Xerox Imaging Systems, and later Scansoft. By 1985, Xerox had gone from 85% market share in 1974 down to just 40%. The 1970s had been rough. Legal issues, new competitors, and no highly successful new products.

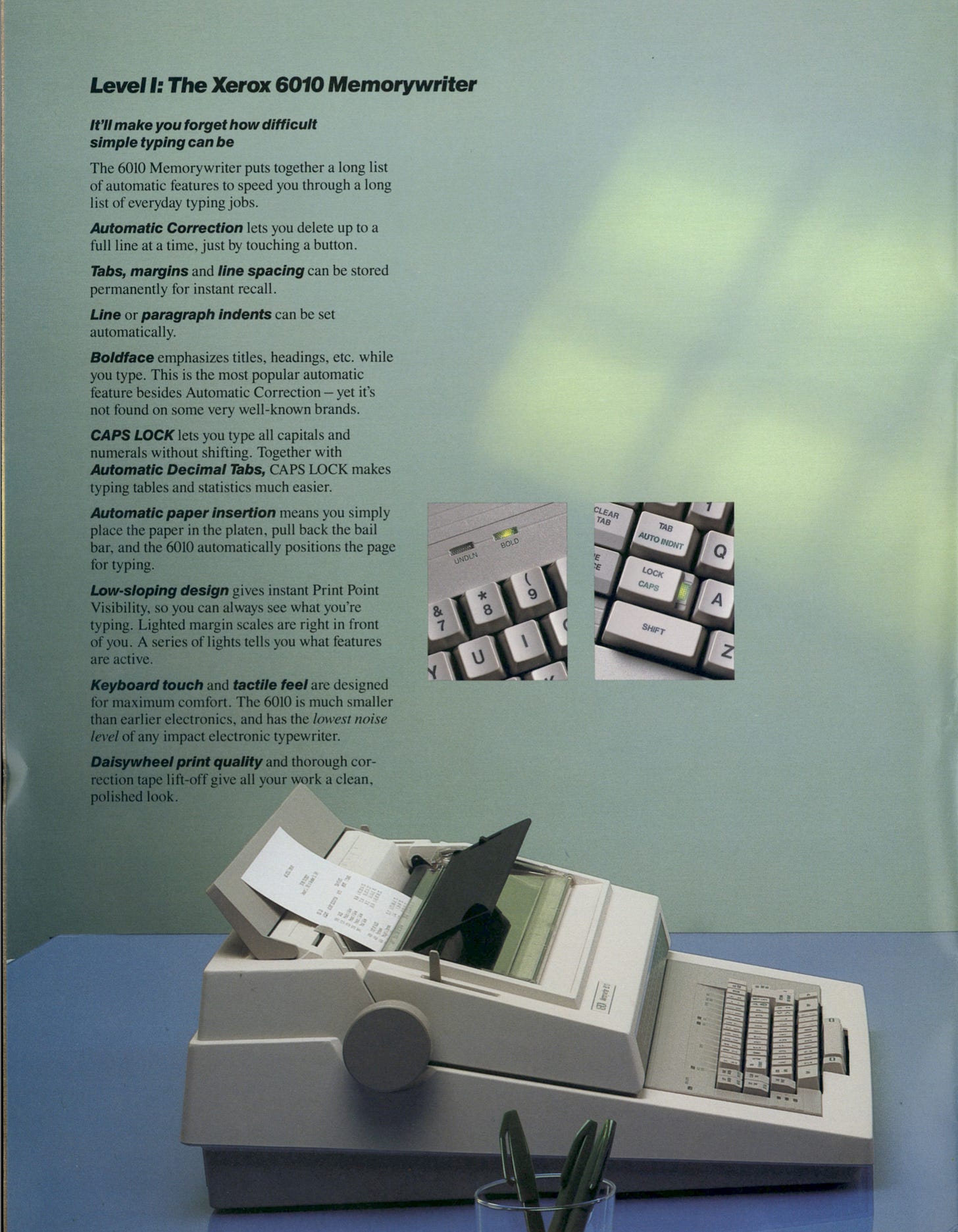

The company had been working to increase reliability and decrease costs, and this kept them alive. But, they finally figured out how to get new technologies to market too. In 1981, Xerox released the Memorywriter electric typewriter. This product was successful, captured more than 20% of the market, and later iterations would add internal memory and other features.

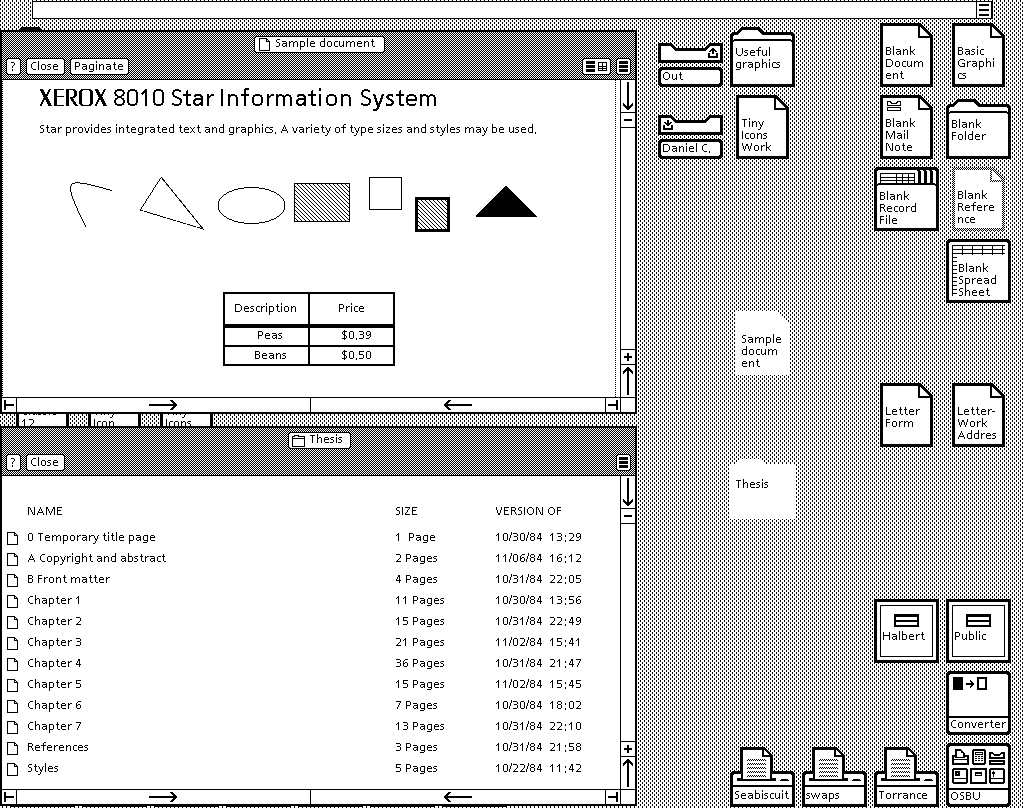

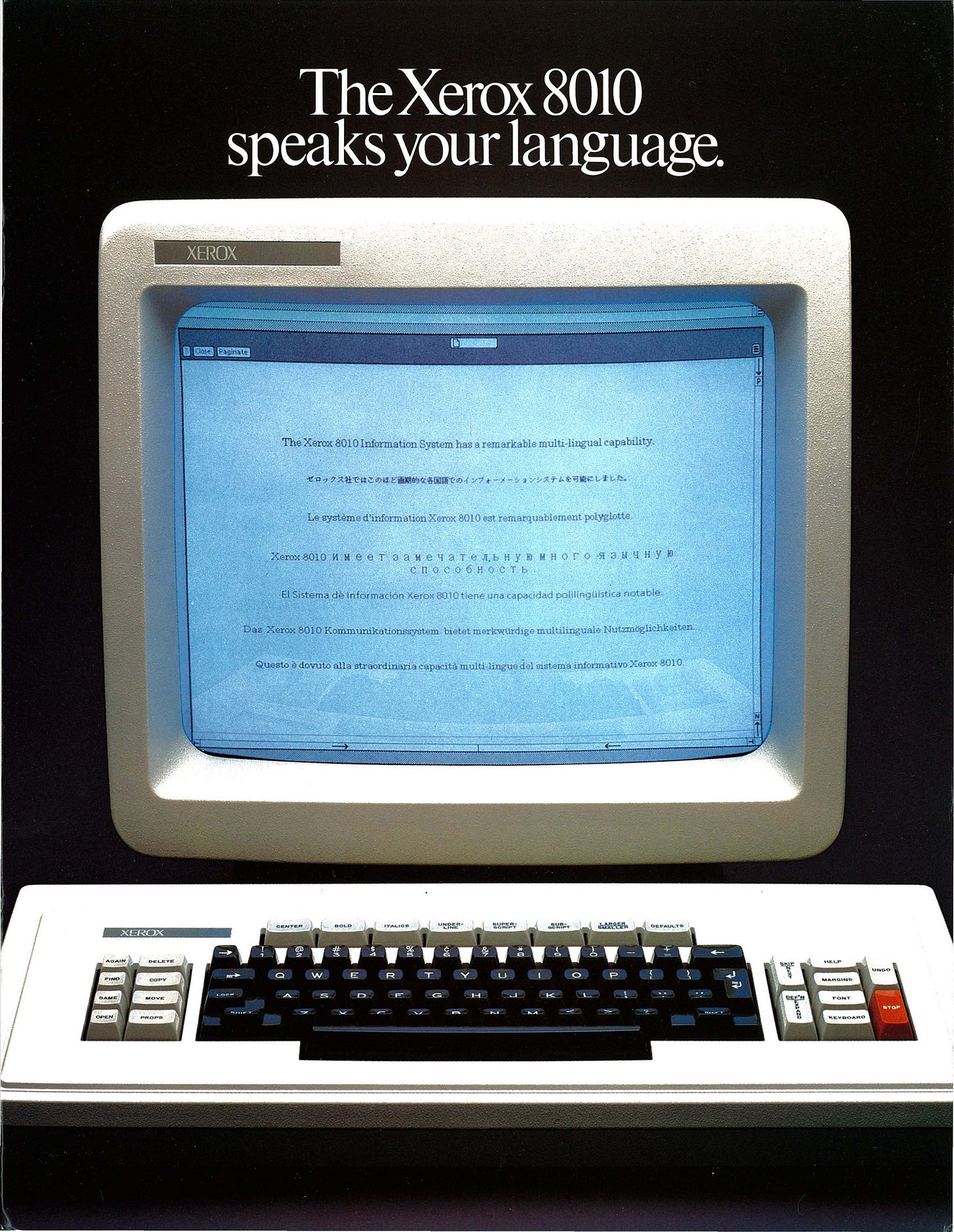

Four years after the Alto was working, one year after the company had a formal method for transferring technology, Xerox began working on a marketable version of the Alto. This work culminated in the Xerox 8010 Star Information System, better known simply as the Xerox Star. This system was built around the AMD Am2900 series with a good amount of microcode implementing an instruction set designed for Mesa, but this could be changed to allow for Interlisp or Smalltalk. The Star shipped with 384K RAM that was expandable to 1.5MB, an HDD of either 10MB, 29MB, or 40MB, an eight inch floppy disk drive, a monochrome seventeen inch display of 1024 by 808 pixels, a two button mouse, ethernet, the Pilot operating system, and the Star desktop software. The system in a base configuration had performance similar to that of the VAX-11/750, and pricing started at $16,000.

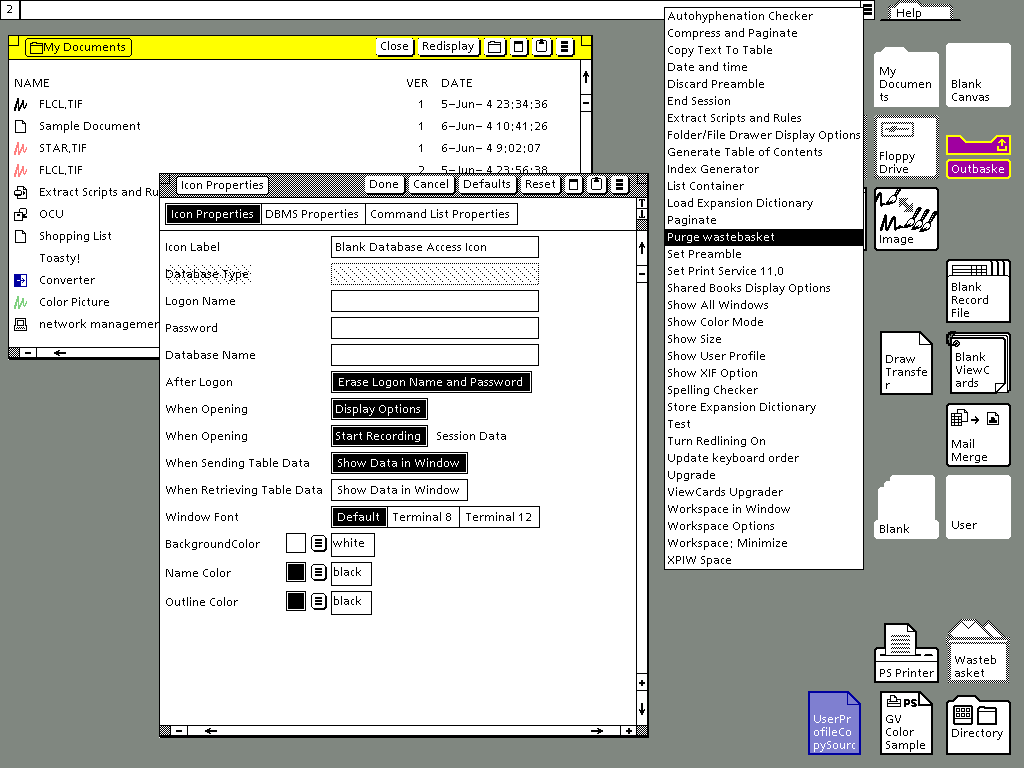

The GUI was more advanced than that of the Alto with skeuomorphic desktop icons, scroll bars on windows, and even toolbars with icons indicating functionality. The system was designed around objects where a document for a word-processing program holds page objects, paragraph objects, and so on. These can be selected, and then opened, deleted, copied, or moved in a standardized manner. The settings of any object could also be viewed in a standardized way, and objects could be embedded into any type of document as the objects were independent. Similar technology would show up on the Lisa and on Windows with OLE.

As the microcode could be changed this led to variations as Lisp machines with the 1100, 1132, 1108, 1109, and 1186 Lisp machines. The final variant was the Xerox Daybreak marketed as the 6085 PCS in 1985. By this time, the system shipped with an 80MB HDD, 3.7MB of RAM, a 5.25 inch floppy disk drive, an ethernet controller, and a PC emulator card with an 80186. When this machine was configured with Lisp as opposed to Mesa, it was the 1186. Display options now included either a 15 inch or a 19 inch display.

Another change over time was that the Star desktop had evolved to be ViewPoint which integrated desktop publishing, word processing, spreadsheets, and databases into a rather seamless suite. This would later become GlobalView for IBM-compatible systems running Windows 3.1, Solaris, or OS/2.

The Star series of workstations weren’t successful. The estimates I’ve read state that only around 25000 were sold. Even within Xerox, the Xerox 820 and 820-II systems running CP/M were more common.

If you’re thinking that the Macintosh UI looks similar to the Star, you’re not alone. Xerox thought so too, and thanks to Apple’s suit against Microsoft, they knew that they might have a case. On the 14th of December in 1989, Xerox filed a copyright suit against Apple, though there was the additional claim that Apple’s suit against Microsoft and HP hurt Xerox’s chances of licensing their own technologies. This case was dismissed on the 24th of March in 1990 with Judge Walker having stated that the proper place for this action would by the Copyright Office and not the courtroom, and that in the case of unfair competition, the matter was really a simple copyright infringement case.

In 1982, David T. Kearns took over as CEO. That year, the company launched the 10-series, Marathon, line of copiers which used microprocessors to allow the use of multiple paper types and more complex functions. The Marathon line was the most successful line of Xerox machines, and it allowed the company to start regaining market share. From the company’s product guide:

Available in five configurations so that you can choose exactly the features you need. Common to all are: automatic double-sided copying from single-sided originals or double-sided originals in the case of Systems 1 and 2; reduction for producing standard copies from oversize originals; the copy quality selector and monitoring system which ensures good quality copies, even from difficult originals. And to keep a record of each user’s copying volume, there’s the option of installing a user code system whereby access to the machine is by entering a personal code.

There’s also image shift which ensures that when you’re doing double-sided copying, the image on the second side is correctly positioned, leaving sufficient margin so that no information is lost in the binding. The Xerox 1075 operates at 70 copies a minute and there’s the innovative visual display screen and instruction panel to guide you through all your copying tasks with words and pictures.

System 5 is the basic 1075 model for straightforward, high quality, fast copying. Systems 1-4 incorporate a selection of practical additions to the basic model.

System 1 with fully automatic document handler and finisher is for when you regularly need lengthy reports copied and stapled.

System 2 is ideal for multi-page documents which do not require stapling since, after copying, they are either to be combined with other material or bound.

System 3 has a semi-automatic document handler (SADH), sorter and computer forms feeder. Suitable if your copying does not include a high proportion of multi-page originals.

System 4 gives speed and convenient one-off copying. The SADH has an integral computer forms feeder which positions and copies continuous stationery like computer printout at up to 35 ‘pages’ a minute.

In 1983, Xerox purchased Crum and Forster, a property casualty insurer, and this became Xerox Financial Services in 1984. XFS then purchased some investment firms. By the late 1980s, XFS represented half of all Xerox revenues.

Between 1988 and 1992, Xerox underwent three restructurings. In the first, the company cut around 2000 jobs, dropped its medical systems group, its electronic typewriter group, its workstation group, and created the new Integrated Systems Operations group aiming to shorten time to market. In 1990, Kearns left the company to become the US Deputy Secretary of Education and Paul A. Allaire became CEO. This led to the next two restructuring efforts. The latter of which in February of 1992 led to another reduction in force of 2500. During all of this, the company brought five new printers to market (4135, 4197, 4213, 4235, 4350), the Xerox 5775 Digital Color Copier, and the DocuTech Production Publisher Model 135. The 5775 in particular marked an important change for the industry: a copier was now a microcomputer presented as a scanner and laser printer with a network interface.

Later in 1992, Xerox developed PaperWorks from PARC’s DataGlyphs developed in 1989. DataGlyphs were a type of stealthy 2D bar code that employed steganography. Essentially, DataGlyphs employed an encoding technique where digital data is converted into a pattern of small dots. These dots are integrated into the existing patterns within an image, like the shading or a gradient. The key was that the placement of these dots was controlled, and the data blended into the image such that humans couldn’t perceive it. PaperWorks software utilized this technology to allow fax machines and computers to exchange information, and it was quite clever. The idea was that a computer equipped with a modem could both send and receive faxes. Combining this was DataGlyphs and OCR could then allow a fax to be both input and output for a computer. In the case of the first release of PaperWorks, this meant that a fax could serve as data to be stored or as instructions for specific data to be sent. As cool as this technology was, it was poorly timed with the web revolution just around the corner.

As though giving a rebirth to Xerox’s early copier-as-a-service model, the company did a bit of a rebrand in 1994 as “the Document Company” and they changed their logo to a digital X. The new business model they pursued was to offer Xerox machines, ink, paper, maintenance, configuration, and user support as a subscription service.

The company’s lines of networked digital MFMs (multifunction machine: scanner, copier, printer, fax) became primary revenue drivers while the older xerographic machines declined. By 1997, the MFMs brought in $6.7 billion. The prices of these machines also declined rapidly, and this brought them into homes via stores like CompUSA, Staples, and OfficeMax.

Richard Thoman had joined the company as President and COO in April of 1997 from IBM. His mission had been to once again reinvent Xerox to allow the company to survive; this time not just computers, but the growing World Wide Web. He’d become CEO in April of 1999, and the company’s share price fell by about 50%. Thoman resigned on the 11th of May in 2000. Allaire returned as CEO and Anne Mulcahy took the role of President and COO. The reasons for this rapid fluctuation in the executive ranks was a combination of issues. First, renewed competition from Canon, Ricoh, Ikon, and others ate into market share and therefore revenue. Second, Brazil had a particularly bad economic crisis in earlier in the year, and Brazil was a major market for Xerox. This forced Xerox to reorganize their global sales force where instead of focusing on geography the sales teams would focus on specific market segments or industries. This was needed, but the implementation was costly and poorly executed. Staff were frustrated, customers were angry, and the company’s sales declined. Additionally, the company now had about $16 billion in debt. By the time Allaire returned and Mulcahy was promoted, the company’s share price had fallen another 10% for a total of about 60% from its price a year prior.

In October of 2000, the company posted a quarterly loss of $167 million, and the SEC began an investigation into the company’s accounting practices. This eventually led to a fine of $10 million for booking lease revenue up front. This further led to five company executives being fined individually for a sum totaling $22 million. The shortfall and SEC investigation led to a string of cost cutting measures that would see around 12,400 people laid off by the end of 2001. On the 1st of August in 2001, Mulcahy became CEO. In early 2002, Kearns retired, and Mulcahy additionally became the company’s chairman. Shortly after, PARC became an independent wholly owned subsidiary of Xerox. From January of 2001 to December of 2003, the company’s workforce shrank from 92,500 to 61,100, but under Mulcahy’s leadership, the company launched more than thirty new products, and posted income of $360 million for 2003. By 2004, the company’s debt had been reduced to under $10 billion. Ursula Burns succeeded Mulcahy as CEO on the 1st of July in 2009.

On the 28th of September in 2009, Xerox announced its acquisition of Affiliated Computer Services for $6.9 billion. ACS was an IT services company of around 74,000 people operating in over ninety countries. ACS’s largest business segments were in electronic toll collection, parking systems, photo traffic enforcement, and non-bank-owned ATMs. After becoming part of Xerox, the IT outsourcing arm of ACS failed to grow. That portion of the company was sold to Atos for $1.05 billion. In January of 2016, shareholder Carl Icahn exerted pressure on the company to make the business services unit (mostly ACS) its own publicly traded company. Burns oversaw this separation, and then became the chairman of the new company, Conduent, on the 1st of January in 2017. Jeff Jacobson then became CEO of Xerox.

Jacobson’s tenure was short lived as was chairman Robert Keegan’s. Fujifilm had been looking to acquire 50.1% of Xerox for $6.1 billion and merge all of Xerox into the existing Fuji Xerox joint venture. Jacobson would have become the CEO of the resulting Fuji Xerox, and Xerox’s shareholders would have gained $2.5 billion. This deal was canceled on the 13th of May in 2018, and John Visentin, one of Icahn’s consultants, became CEO. He’d previously held positions at Hewlett-Packard and IBM. The Icahn led board then proceeded to attempt a takeover of HP which failed. That offer was canceled on the 31st of March in 2020.

Steve Bandrowczak became CEO on the 3rd of August in 2022. Xerox PARC was donated to SRI International in April of 2023, but Xerox kept its patent rights. PARC became SRI’s Future Concepts division on the 18th of January in 2024. On the 2nd of July in 2025, Xerox completed the acquisition of Lexmark International for $1.5 billion. For the year of 2024, Xerox’s revenue was $6.22 billion, assets totaled $8.37 billion, and net income was negative $1.3 billion.

Xerox is a company that changed the world more than once. Xerography alone changed the world with easy, low cost, low mess copies. The technology was so successful that Xerox became a verb. PARC’s innovations further transformed the world with EDA, ethernet, and GUIs. While many people say that Xerox was a company that could have been IBM or Microsoft, or some crazy combination of the two, I do not believe this to have been the case. Xerox didn’t have the necessary culture, business practices, and business relationships to achieve the Macintosh or the DeskPro 386. The Alto was too early, too expensive, and lacked a user-friendly design. The Star was too expensive, lacked the user friendliness of its competitors, and it didn’t fit in well with the rest of Xerox’s business. For Xerox to have truly succeeded in the computer business, Xerox would have needed to have transformed itself into a computer company. This was never in the cards. Xerox did well with copiers, and they incubated the future of our world. I’d say that they were plenty successful. Thank you to the fine folks who built, worked at, and supported Xerox over the years. Your contributions to the world are astounding and much appreciated.

My dear readers, many of you worked at, ran, or even founded the companies I cover here on ARF, and some of you were present at those companies for the time periods I cover. A few of you have been mentioned by name. All corrections to the record are sincerely welcome, and I would love any additional insights, corrections, or feedback. Please feel free to leave a comment.