Remington Rand

The second life of UNIVAC

This is the third installment of a series. You may be interested in The ENIAC as well as The Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation.

James Henry Rand Junior was born on the 18th of November in 1886 in North Tonawanda, New York. He received his bachelor's degree in 1908 from Harvard University. After graduating, he went to work with his father at Rand Ledger Company. He married Miriam Smith in 1910. Aside from business, he loved speedboats, raced them, and was successful in his hobby. He ran his father’s company for the years 1910 to 1914 while his father was suffering from an illness. When his father recovered, the two business men parted ways. They rather seriously disagreed on advertising, and they somewhat disagreed on product ideas. The Rand Ledger Company’s product was essentially a paper database system. It involved dividers, file tabs, and index cards along with instructions on how to develop your organizational system. The younger Rand had some rather innovative ideas around this system and following he and his father’s dispute, he created the Kardex Visible Record Control. In the product manual for Kardex VRC, we see the information problem of that time period rather well stated:

If control is to be recaptured, record equipment and procedure must be geared to the times again. There must be replacement of inefficiency and modernization of the obsolete. Then the cost of record keeping may return to more profitable proportions and its products may contribute more substantially to the solution of problems of management.

The younger Rand’s company was American Kardex, and it was rather immediately successful. Rand Ledger and American Kardex were among the largest office supply companies in the USA. Mary Rand (the elder Rand’s wife and younger Rand’s mother) negotiated an agreement between the two men. Rand Ledger purchased American Kardex and the newly combined entity was known as Rand Kardex starting in 1925. This combined company was the single largest office supply company in the USA upon formation. The company’s market dominance was most easily seen in the the attempt by Rand Kardex to acquire Globe Wernicke. This was stopped by the US government in early December of 1926 via an antitrust lawsuit.

The Rand Kardex Corporation was powerful, and the two Rands saw an opportunity for some vertical integration. Their company manufactured the cards and storage systems, but they did not supply their customers with the typewriters that put data on the cards. Rand Kardex acquired the Remington Typewriter Company on the 25th of January in 1927 and formed Remington Rand. The Remington Typewriter Company was no small operation. The company had developed the first silent typewriter in 1909 and the first electric typewriter in 1925. This amalgam of office companies became even more acquisitive gobbling up the Dalton Adding Machine Company, Powers Accounting Machine Company, Baker-Vawter Company, Kalamazoo Loose-Leaf Binder Company, and a few others.

By the late 1920s, Remington Rand was still dominant in office supplies, and they were a strong player in office machinery. Mechanical tabulating machines, punched cards and punchers, information storage and organization, mechanical calculators, and typewriters made up the bulk of the business. The company’s sales revenues stood at $5 million in 1927; roughly $91 million in 2024 dollars. This may seem small, but the country was smaller in population and less than ten percent of the working population were engaged in office work. On those terms, these are extremely impressive figures. This should have been a great year for Rand Junior, but he lost his wife in 1927. In 1929, he became chairman of the company and married Evelyn Huber. Again, one would assume that he was on top of the world, but then came October. On Monday the 28th, the Dow dropped thirteen percent. The following day, it dropped another twelve percent. By the middle of November, the Dow had lost half of its value from one month earlier. The Great Depression had begun, and Remington Rand largely manufactured goods that companies bought when they were doing well and looking forward to expansion. Sales for Remington Rand were cratering. In 1931, the company suspended dividend payments and closed the year with just $1.25 million in sales revenue. Rand lost his wife Evelyn in June of 1934. With his business a shadow of its former self, two loves lost, and the country seemingly unable to recover, I imagine that Rand’s view of the world at this time was extremely dark.

The company resumed dividend payments in 1936, but don’t let this fool you into thinking that this was a great year. The American Federation of Labor had been organizing workers in 1934 which led to two years of negotiations, a small strike, and union busting efforts. Over the 25th and 26th of May in 1936 a few thousand workers across Remington Rand factories abandoned their stations as part of a labor strike following the company’s acquisition of a typewriter factory in Elmira, New York.

Yet, the cuts and consolidations being made that so enraged Rand’s employees were absolutely necessary. Remington Rand had been built of acquisitions which piled up debt and created a large number of redundancies. The company had twenty nine manufacturing facilities at its highest count. By 1936, just fifteen of these remained with one major product being made at each, and three of these produced typewriters: Middletown, CT; Syracuse and Ilion, NY. The burden of redundancy, debt, and a massive sales staff meant that for the year 1935, revenues of $35 million produced just $1.7 million in profit. Compare that to IBM, Remington Rand’s competitor, who for the same time period made a profit of $6.6 million on revenues of $21 million.

The strikers’ demands were a twenty percent increase in wages, and a guarantee that production would not be moved to Elmira. It’s easy to see why the factory workers would be upset. They’d just been through a lengthy process of negotiations between the company’s leadership and the workers’ unions while Remington Rand closed various factories, laid off staff, and fired several labor organizers. Many of these folks rightfully feared for their jobs. The strike was long, violent, and litigious. I cannot really say that either side of this acted in a laudable manner. On Rand Junior’s part, he seemed to be possessed with maintaining control and profitability of his company. I can imagine that this was fueled by tragedy in his personal life, but it cannot excuse the moral failings on his part throughout the strike. On the side of the organizers, their fears were legitimate, but that doesn’t excuse assault, vandalism, and theft. Despite the tribulations, the company survived and Rand Junior managed to avoid legal repercussions. The National Labor Relations Board ultimately ruled in favor of the workers on the 13th of March in 1937, and the unions approved a settlement with Remington Rand on the 21st of April. The factory in Middletown was ultimately closed, and the production of typewriters consolidated to Elmira and Ilion.

Just as the company was starting to regain its composure, the United States entered into World War II. The company retooled to manufacture weaponry, and more specifically, pistols. Remington Rand received its first order on the 16th of March in 1942 for one hundred twenty five thousand M1911A1 pistols. These weapons were manufactured in the former Syracuse typewriter factory that had been closed following the strike. Unaccustomed to producing fire arms, the company initially struggled. They resorted to purchasing some parts that they couldn’t produce from other companies. Barrels, grips, safeties, and slide stops were bought from Colt and Springfield. The first production pistols were accepted by the US in November of 1942. While these first units performed well, there were some problems. Primarily the parts produced were not totally interchangeable with other 1911s. This wasn’t acceptable. In March of 1943, production was stopped. Rand Junior order inspections, changed management, and production was resumed in May of 1943. By the end of 1945, Remington Rand had produced nearly a million pistols. They were not only the cheapest 1911s around, but also by far the most numerous and of the highest quality. The war also saw Remington Rand produce quite a bit of office equipment for the US government.

In 1943, Loring P. Crosman approached Rand Junior with the plans to build an electronic computer. Rand was impressed with the idea, and hired him. A new lab was built in Norwalk specifically for this type of work. The lab opened in 1946 and Crosman’s team moved in. In 1948, this group was moved into a repurposed barn (or it was called the barn, but was in fact an old carriage house?) on the grounds of the new Remington Rand headquarters in Rowayton about three miles from their previous location. By the end of that year, Crosman’s designs were demonstrated to be sound. This was the Model 409; essentially a programmable calculator. Data was entered with punched cards, and it was programmed with via plugboard. The 409 was about seven feet long, two feet deep, and five feet tall. It weighed in around thirty two hundred pounds. The punch card unit was roughly the size of a refrigerator. According to Bill Wenning who joined Crosman’s eight person team in late 1948, the work was extremely exciting, involved a lot of improvisation while working twelve hour shifts, and was ultimately quite successful. The machine worked.

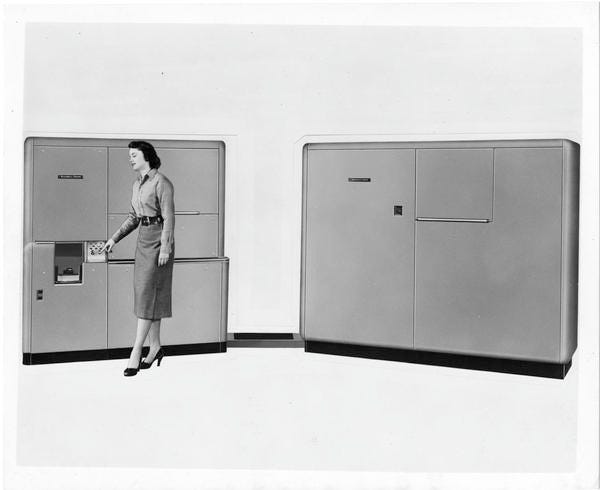

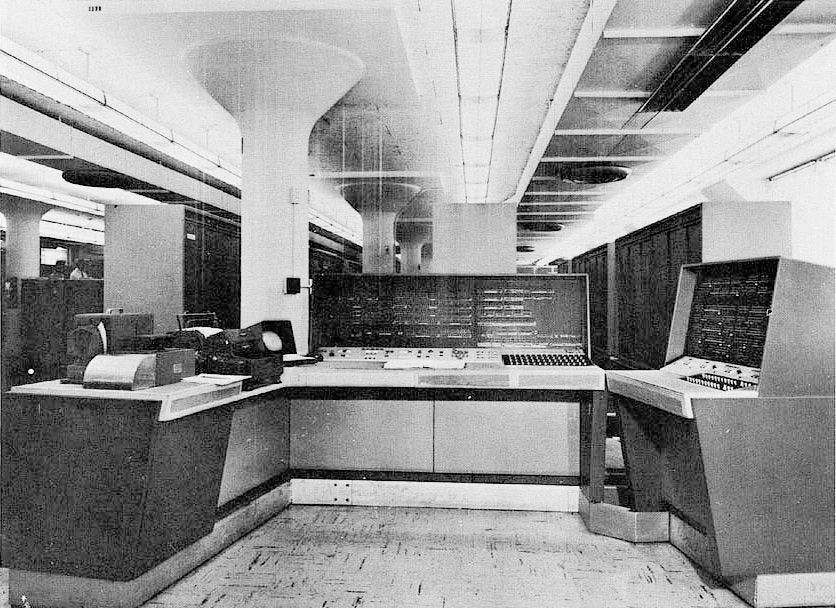

I have read one account that orders for the 409 had started in 1948 and were halted in 1949 due to backlog. Not a bad problem to have really. Most accounts talk about the 409 being the lower-priced offering against other machines. This is likely because Remington Rand purchased the Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation on the 15th of February in 1950. With this acquisition EMCC became the Eckert-Mauchly Division of Remington Rand (EMDRR) and the 409 became the UNIVAC 60 released in 1952 and the UNIVAC 120 released in 1953. For these models, the 60 and the 120 were the number of columns on the punched cards read by the machine. These were programmable calculation systems, but not Turing-complete computer systems. The first complete computer system offered by Remington Rand was UNIVAC as designed by EMCC. The primary change to UNIVAC at Remington Rand was the addition of the UNITYPER input system by Admiral Grace Hopper.

Remington Rand wasn’t content with just EMCC, and the company acquired Engineering Research Associates in 1952. ERA’s 1101 became UNIVAC 1101 despite having nothing in common with UNIVAC I. The 1101 had related machines 1102, 1103, 1104, and 1105. These various UNIVAC machines together with Remington Rand’s other office products brought the company to revenues of more than $224 million in 1954 with about $27 million in profit. A total of forty six UNIVAC I systems were built and delivered.

In 1953, IBM shipped the Model 701, and the company formed SHARE in 1955. Roughly seventy six IBM machines were deployed at customer sites. In the mid-sized computer market that Remington Rand wasn’t in, IBM had over three hundred machines deployed with more than nine-hundred ordered. Remington Rand had already lost their lead. Remington Rand was purchased by the Sperry Corporation on the 30th of June in 1955. At this time, James Henry Rand Junior was sixty eight years old, and he became the vice chairman of Sperry Rand. he retired three years later and moved to The Bahamas with his wife Dorothy.

An oft cited reason for Remington Rand so quickly losing to IBM is the company structure. ERA and EMCC were never integrated at Remington Rand. EMCC was in Philadelphia while ERA was in St. Paul. They had different cultures, different technologies, and different markets. EMCC was meant to serve the business market from the outset while ERA was more of a government contractor. I am sure these matters contributed to IBM’s success against Remington Rand, but I believe the true failure was in sales. IBM’s sales teams emphasized the work that their machines could do like getting payroll done quickly and accurately. They sent programmers, engineers, and businessmen to clients to assist with sales, setup, and service. The UNIVAC sales people generally emphasized the machine and its specifications, the superiority of UNIVAC when compared to other computers, and they were otherwise more knowledgeable about Remington Rand’s non-computerized information systems. Adding to this, the structure of the sales that Remington Rand did make was poor and sometimes had them at a loss. They made fixed-fee contracts that failed to accurately consider the costs of service and support. The most famous such contract was with the Atomic Energy Commission for the Livermore Atomic Research Computer. This contract was made for $3 million, but the total cost for Remington Rand ended up being $20 million.

I have readers from many of the companies whose history I cover, and many of you were present for time periods I cover. A few of you are mentioned by name in my articles. All corrections to the record are welcome; feel free to leave a comment.