The other Apple RISC machines

Apple and the PowerPC era

After the IBM 801 and the IBM RT PC in the 70s and 80s, IBM continued working on RISC CPUs and system designs. The first result of that work was the RIOS-1. This was a 10 chip design that included: instruction cache, fixed-point, floating-point, 4x L1 cache chips, storage control, input/output, and clock. RIOS was innovative in many ways being the first microprocessor with out of order execution, the first microprocessor with register naming, and the first IBM POWER design. The first machines using the RIOS were released in 1990. These were the RISC System/6000 machines which were divided into POWERServers and POWERStations. A version of the RIOS-1 implemented in a single chip was released in 1992 and called RSC (RIOS Single Chip), and a variant of this chip was radiation hardened and called the RAD6000. The RAD6k was used in MESSENGER, Spirit, and Opportunity among other spacecraft.

The 68k Macintosh line was failing to keep pace with the IBM PC compatible market by the end of the 1980s. In the early 1990s, the pressure was on for Apple to do something, and Apple hadn’t been sitting idle. Two separate projects were attempting to resolve this. One was Acquarius. The Acquarius project was working on a CPU called Scorpius, a quad core RISC CPU with separate instruction and data caches shared by the cores, and an MMU and bus interface shared by the cores. This project failed to make much progress and was eventually discontinued. The second project was called Star Trek. This was a joint venture between Apple and Novell with support from Intel. The goal of this project was to port Apple’s System 7 to the Intel 486. The thought was to have System 7 run on top of DR-DOS, and as the team slogan said: To boldly go where no Mac has gone before. This was successful but faced three serious issues. First, the existing library of Macintosh software would have needed to have been ported individually to the x86 architecture. Second, the politics within Apple made this project extremely controversial. Third, when the ported System 7 was shopped around (including to IBM), there weren’t any seriously interested parties. When Michael Spindler replaced John Sculley, the project was terminated.

Then, there was IBM. They had completed the creation of their new RISC CPUs and needed customers. HP, Sun, and SGI had their own RISC CPUs and wouldn’t make for great IBM customers. Yet, Phil Hester (head of RISC at IBM) remembered the call from Apple’s Star Trek team, and suggested that IBM contact them about a hardware deal. Apple was interested.

A few modifications would be needed for Apple’s uses. Apple had already been working on prototypes developed around the Motorola 88k series CPUs. To avoid completely redesigning their boards, they needed the POWER CPUs to be compatible with the 88k bus architecture. As a result, Motorola was brought into the project. This formed the AIM (Apple, IBM, Motorola) alliance, and the redesigned IBM POWER chips were known as PowerPC.

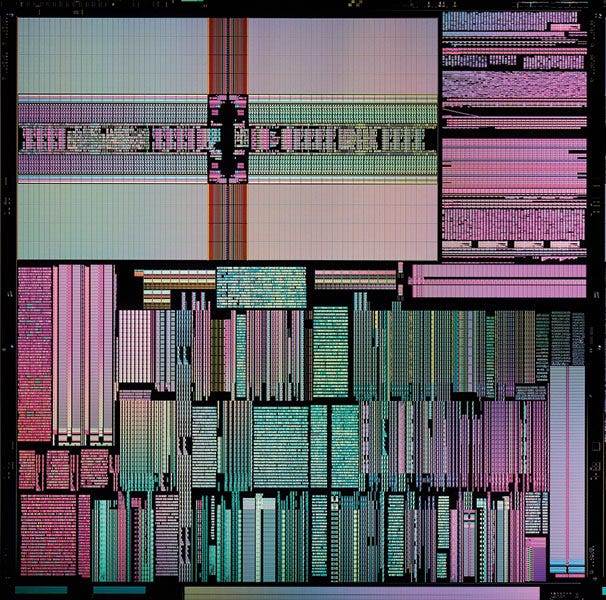

After 21 months of work (starting October of 1991), the first CPU from the AIM alliance was the 32 bit PowerPC 601 which started volume production in July of 1993. It was manufactured on 0.6 micron process, utilizing 2.8 million transistors, with a 32KB L1 cache, and had a top clock speed of 80MHz. The die size of the 601 was 121mm squared. The first computers to feature the 601 were from IBM: PowerStation M20, PowerStation 25W, PowerServer 25S, PowerStation 25T.

Back at Apple, the 601 was in the Power Macintosh 6100/60 clocked at 60MHz. The system bus speed was 30MHz, and the 8 to 136MB of 72 pin RAM had to be shared with the graphics chip unless a video card was added to the machine. From Apple, the 6100/60 had either a 160MB or 250MB SCSI hard disk drive, a 2x CDROM drive, a 3.25” floppy drive, and a single PDS expansion slot. The operating system at launch of the 6100/60 was Macintosh System 7.1.2. Apple had wanted to catch up with the WinTel machines, and they did. The 6100 was the entry level Power Macintosh, and it was roughly 5% faster than a 60MHz Pentium machine. The primary issue cited was that m68k software from pre-PPC Macintoshes ran more slowly on the 6100 than it did on those older machines, but customers didn’t seem to mind. From announcement to launch on the 14th of March in 1994, Apple had sold 150,000 machines in pre-order. One million PowerPC based Macintoshes would be sold by the year’s end. December of 1994 also marked when Apple began its licensing of the Macintosh platform. For the first time, a 3rd party systems manufacturer could produce and sell a Macintosh computer.

Apple’s operating systems were suffering from stagnation in the same way that the Motorola 68k Macintoshes had been. To solve this problem, Apple bought NeXT Computer. With that acquisition, Apple gained a modern UNIX operating system. This acquisition also brought Steve Jobs back to the company. He became CEO on the 9th of July in 1997.

Unfortunately, the success of the 6100 and other PowerPC Macs was short lived. Apple was in a dire financial position at this time. Shortly after Jobs came back to the company, Apple itself was streamlined. 70% of all products were discontinued. 3000 employees were laid off. Then, as Microsoft was coming under some legal heat for antitrust allegations, Jobs got a deal for a $150 million dollar investment from Microsoft as well as a commitment from Microsoft to continue developing software for the Mac.

Clone makers were occasionally innovating faster than Apple. Buying an Apple often meant paying more for less performance with the same software. For example, the PowerMac 9600 at 350MHz was more expensive than and also slower than the 266MHz Motorola StarMax 6000 XL. The StarMax line also used PS/2 mouse and keyboard ports, SVGA video, manual eject floppy disk drives, ATX power supplies, and standard PC form factors. Apple sold 4.5 million computers in 1995. This dropped to 1.8 million through the first three quarters of 1997. Clone makers sold roughly 600,000 in those same three quarters. Revenue per system also fell. In response to rapidly declining sales and revenue, Apple ceased licensing the Macintosh platform to 3rd party manufacturers on the 2nd of September in 1997. The largest clone maker had been Power Computing. Apple purchased this company the same month, September of 1997.

In November of 1997, Apple launched the Apple Store as an online, build-to-order store. Closing out the year, Apple lost $878 million.

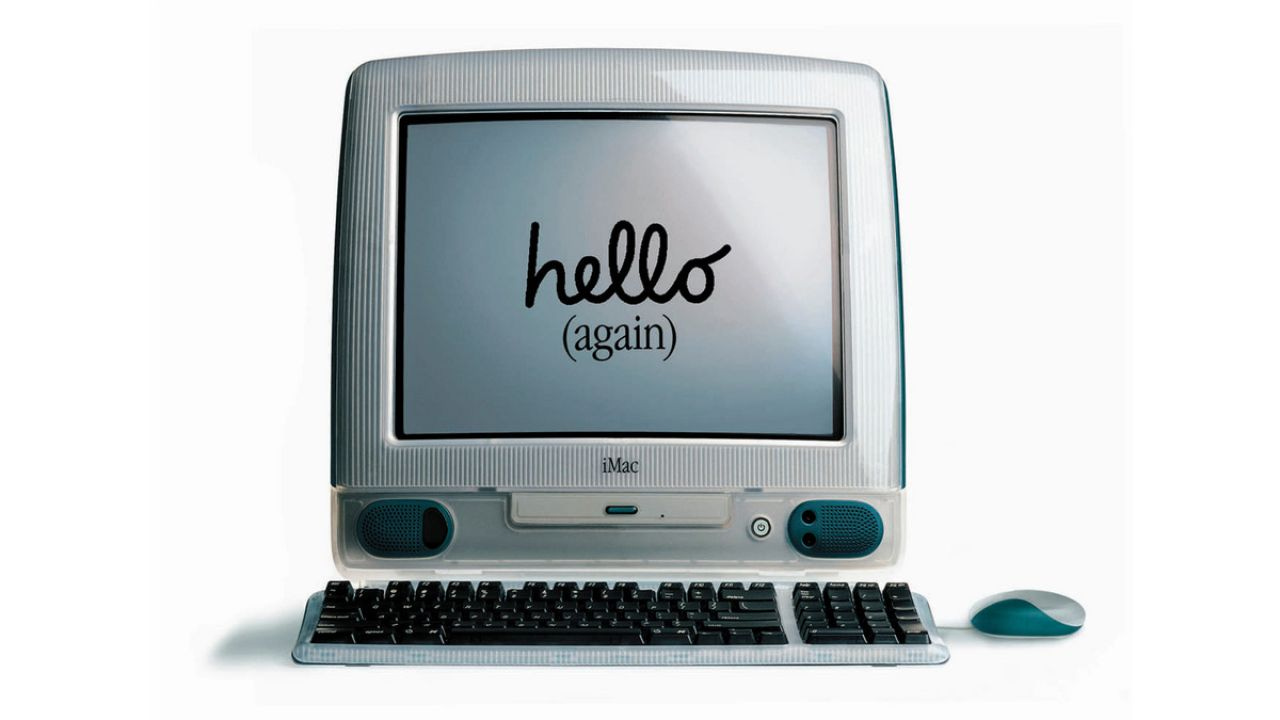

Jobs had a vision for just four products as part of his product streamlining strategy. He wanted a consumer desktop, a professional desktop, a consumer laptop, and a professional laptop. For the consumer desktop, the machine needed to prioritize easy internet connectivity, needed to be ready within a single year, needed to be inexpensive (in Apple’s terms of inexpensive), and needed to drop both legacy and proprietary technologies where possible. Steve Jobs unveiled the iMac on the 6th of May in 1998.

The first of the iMacs was Bondi blue. It, like all later G3 iMacs (and many other G3 Macintoshes) had a casing made of clear plastics. The first iMac G3 shipped with a 233Mhz PowerPC G3 processor, 32KB of L1 cache, 512KB of L2 cache, two SO-DIMM slots with 32MB of PC100 SDRAM, an ATI Rage IIc with 2MB of SGRAM, a 4GB IDE hard disk drive, a 24x tray-loading CDROM drive, 10/100 BASE-T ethernet, a 56k modem, 2x USB ports, 2x headphone jacks, stereo speakers, and a 4Mbit/s IrDA. While it weighed 40lbs, it did have a handle… The first G3s also ran Mac OS 8.1.

The initial press reactions to the iMac were mixed, but the consumer response wasn't: 278,000 sold in the first 6 weeks, 800,000 in the first 20. The iMac was the best selling desktop computer in the USA for 3 months following its release with half of those sales being to new computer buyers, and around a fifth of those sales being to folks switching from Windows PCs. Apple’s world-wide market share shifted from 3% to 5%. By the end of 1998, Apple was once again profitable. The 5 millionth iMac was sold in April of 2001.

Mac OS X was released in 2001 and its Aqua interface mirrored the curves and translucency of the G3 Macintoshes. With OS X, the modern UNIX that Apple had purchased with NeXT was transformed into an operating system that was familiar to long-time Apple customers, yet far more powerful for modern computing tasks.

Unfortunately, the PowerPC processors weren’t keeping up with the competition anymore. The G4 line would introduce many amazing machines, as would the G5, but Apple needed to change. The PowerMac G5 brought both a 64 bit quad core CPU and PCIe to the PowerPC line of Macintoshes, but it would be the last PowerPC Macintosh with its final model being released in late 2005.

While the PowerMac G5 was a powerful computer for its time, it also used quite a bit more electrical power, generated more heat, and weighed more. This was, unfortunately, the ultimate problem for Apple’s first line of RISC machines. Intel was offering excellent performance with lower power requirements and cooler operation. Laptops were becoming more common, and this meant weight and size were a serious concern for buyers.

For a few years in the beginning of the 2000s, Apple was a commercial UNIX on RISC workstation vendor. Unlike all of the other companies in that segment, Apple turned into a UNIX on RISC company to save itself, while all of the others went out of business. Now, in the 2020s, Apple is again a commercial UNIX on RISC workstation vendor, but this time Apple is among the largest most powerful companies on the planet.

Fascinating stuff. I never knew that PPC was a RISC chip, nor the history of its development. Thanks for sharing!