The other fruit company, Apricot

Consistently overcoming obstacles

Roger Foster was born in 1941 (as far as I can gather), and graduated from grammar school at 16. Foster’s first professional job was as a chartered accountant, at the age of 21, for GKN (an automotive and aerospace conglomerate). At his two year mark in their accounting department, he shifted over the computer side of the company. Third generation mainframe computers were starting to roll out to the market at this time, prices had come down some, and the market had grown dramatically.

Foster founded Applied Computer Techniques in 1965 in Birmingham in the UK. Leveraging his skills in accounting, among the company’s first products were accounting software packages. At the time, most software of this kind was bespoke, but ACT sold the software premade, prepackaged, and for a lower cost than any bespoke package could manage. This simplified support as all of the software was the same, decreased setup time for customers as the software was premade, and increased profits for ACT as the software was only made once and was sold many times. The next major offering from ACT was computer time. Most companies couldn’t afford a computer of their own. ACT couldn’t either. ACT rented time (primarily at night) on a mainframe computer at English Sewing Cotton in Manchester, and they resold that time to their customers. This meant that after work Foster and his work mates would have to drive over to Manchester, run customer programs and data, go home, then come back later in the night or early in the morning to gather all of the output.

The first year in business, ACT lost some money. Foster and his coworkers had to turn to family for funding, and Foster leveraged his home. After their second year, ACT was able to report a modest profit. Customer relationships were quite strong and ACT was able to count on repeat sales and service charges, and the company received a bid in 1971. Foster didn’t want to sell and he therefore chose to buy out the other two stock holders. In 1973, ACT reported £1 million in profit (roughly £10.1 million in 2023).

The Intel 8080 was released in April of 1974. The 4004 and the 8008 were released prior, but the 8080 was the chip that launched the microcomputer revolution. This revolution wasn’t quick. The shift away from mainframes and minicomputers would be quite long, but the future was plain to see for those who wished to look. By the late 1970s, premade microcomputers that were relatively user friendly were being sold at retail. ACT purchased Petsoft, run by Julian Allason, which made software for the Commodore PET and shipped on cassette. The company also sold its first microcomputer which was the ACT 800 (manufactured in the USA). This was essentially a Commodore PET but with the 6502 clocked at 2 MHz and shipping with an external 5.25 inch floppy disk drive. While the ACT 800 did sell, it was never a really a success. In 1979, Foster floated the company at a market capitalization of £3 million (roughly £13.8 million or $17.7 million in 2023).

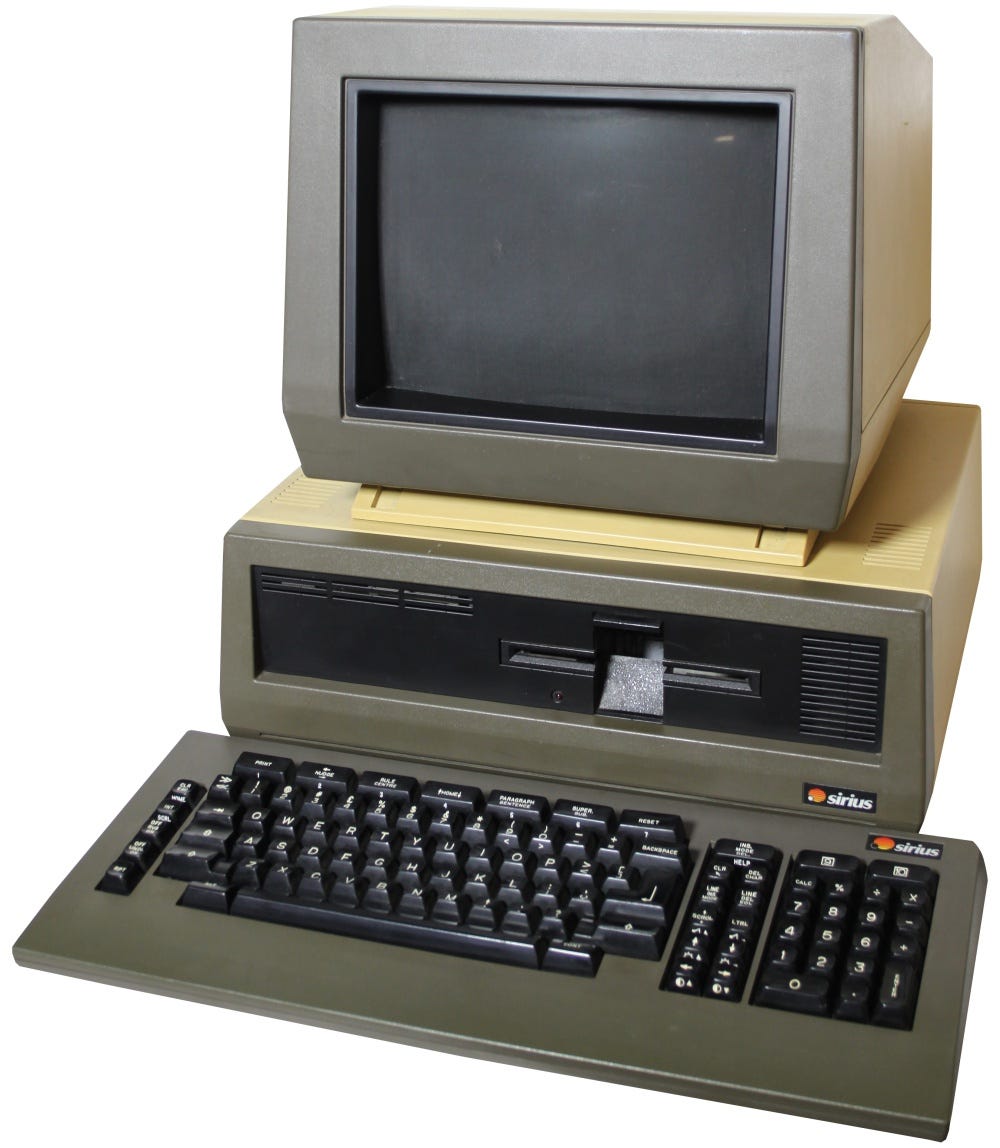

In late 1980, Chuck Peddle left Commodore and founded Sirius Systems Technology in Scotts Valley, California. Here, with 7 other folks, he would make the Sirius 1 which would release in 1981. This was an Intel 8088 machine clocked at 5 MHz, packing 128K RAM standard (expandable to 896K), a 5.25 inch 1.2 MB floppy drive (with a second drive optional), 800x400 video output, and running CP/M-86. MS-DOS was released for the Sirius 1 shortly after the machine’s launch.

As one may guess from the release date, this machine was not IBM PC compatible. While the hardware had some similarities, they were very different machines. The Sirius 1 used a different BIOS, different video chip, and different audio. The keyboard also featured programmability, and the disc recording method was incompatible with that of the PC. Peddle needed software written for his computer, and he approached ACT about this. Foster and his company were happy to oblige, but they also wanted to distribute the machine in the UK (Barton distributed the machine in Australia, and Victor Comptometer distributed the machine in other markets as the Victor 9000). For ACT’s side of things, they had software as well as 800 dealers in the first year. This was huge for ACT. The Sirius 1 accounted for 80% of ACT’s sales by 1983. The Sirius 1 was the first popular 16 bit computer in Europe claiming the number one spot. Things were looking good for ACT and for Sirius.

In November 1982, Sirius Systems Technology acquired Victor Comptometer and the name of the combined company became Victor Technologies. Unknown at the time, the incredible success of the Sirius 1 and the new company wouldn’t be long lived. Sirius/Victor grew extremely quickly as sales were great and demand was high, but those sales stopped just the next year. The company had some large debt obligations and had swollen in size making 1983 a bad year for Victor. Chapter 11 proceedings began in February of 1984 and Datatronic AB purchased Victor in February of 1985. Zero to $250 million and back to zero in just four years. In hindsight, the success of the Victor in Europe could be attributed to IBM’s delay of the European launch of the PC by 18 months. As soon as the IBM PC was available, the sales of the Sirius 1 cratered.

For ACT, the failure of Victor was a very real threat. The folks at ACT began working on a new microcomputer in 1983 when the first signs of trouble were visible. They were working in the garage of a house in Dudley, and within 12 months they’d designed their fist computer, established an R&D department, and built a factory in Glenrothes, Scotland.

All of this work resulted in the Apricot PC which was released in September of 1983. This machine featured an Intel 8086 clocked at 5 MHz optionally paired with an 8087 math coprocessor, 256K RAM standard (expandable to 768K), one or two 1.4M Sony 3.5 inch floppy disk drives (drives with disc capacities of 315k or 720k were also available), one serial port, one parallel port, a modem, two expansion slots, 9 inch or 12 inch green phosphor screen capable of 80x25 in character mode at 10x16 or 132x50 in character mode at 6x8 or 800x400 pixels in graphics mode (a color board was available and could deliver 16 simultaneous colors). All of the I/O was handled by the Intel 8089. While the machine came with an integral modem, an Apricot LAN card was also available. The computer could optionally also come with a 5M or 10M Winchester hard disk, which would then mean only floppy disk drive could fit in the machine. That this computer was rather small was often touted in ads:

It is possible to transport your Apricot pc by a unique arrangement for attaching the keyboard to the underside of the systems unit. A shutter slides down to cover the disk drives and a carrying handle pulls out from the systems unit for ease of carrying. The monitor also has an integral carrying handle

That ACT was originally a software company is visible in how much attention they gave to the software library for this machine. As their ads called it “Inclusive Software”:

MS-DOS 2.11, GSX Graphics System Expansion, Utilities, Microsoft BASIC Interpreter, Configurator, SuperCalc, SuperPlanner, SuperWriter, CBASIC-86, C Language Compiler, Pascal/MT+ 86, PL/1, Level 11 COBOL with Forms 2, Level 11 COBOL Animator, Assembler plus Tools, Display Manager, Access Manager, MBASIC Compiler, FORTRAN, Pascal UCSD, MS COBOL, MS Assembler, Personal BASIC

While MS-DOS was standard on the Apricot PC, CP/M 86 and Concurrent DOS were available as well. The Apricot PC featured a menu system to navigate MS-DOS which met with mixed reviews. Beyond being small, somewhat transportable, powerful for the time, and featuring the latest in storage media, the Apricot had a rather interesting keyboard. This was a full-travel, mechanical, 101-key, QWERTY keyboard. Eight of the function keys were standard keys, but six of them were touch sensitive (membrane) keys and there was an LCD display built into the keyboard. This could either label the 6 membrane keys, or it could function as a clock/calendar or as a calculator. The calculator function was activated by hitting the Calc button, and operated with the right-hand numeric keys like a pocket calculator.

All of this glorious hardware and software would set the buyer back anywhere from $2295 to $4895 depending upon the configuration (roughly $6700 to $14300 in 2023).

By July in 1984, ACT employed 90 people and produced 4000 computers per week. The company could supply both hardware and software, and they must have felt safe from Victor’s failures. Following the Apricot PC, ACT launched the Apricot F1 for the home market, the PC Xi for the business market, and the F1e for the education market.

ACT’s computers were selling well and reviews were positive. By the start of 1985, Apricot held about 30% of the UK microcomputer market and they were a strong competitor in the wider European market. Profit for the year would total to £10.6 million (around £30.6 million in 2023 or about $39 million). Not content to be on a single side of the Atlantic, ACT renamed itself Apricot Computers, ran some large ad campaigns in the USA and Europe, and recruited dealers whom Apple had abandoned.

Apricot was still shipping non-IBM compatible machines in 1985, but they could feel the winds changing. The last non-IBM compatible machine was the XEN (a 286 machine). The XEN was followed by the Apricot XEN-I (codenamed Candyfloss). Unlike its predecessors, this machine shipped with a 5.25 inch floppy drive due to IBM’s usage of that form factor. The XEN-I shipped with a 386 at its heart. Unlike many machines of the era, Apricot chose to ship GEM from Digital Research as the GUI for this particular machine.

The XEN-I and its derivatives sold for a few years and later models took on decidedly more “IBM” keyboards and mice.

In 1989, Apricot brought the world’s very first 486 IBM-compatible PC to market with the Apricot VX FT. This was a server machine that used IBM’s Micro Channel Architecture. Depending upon the configuration and intended use, the VX FT could ship with MS-DOS 4.01, OS/2 Extended Edition, SCO Unix System 3.2, Novell NetWare, 3+Open, Microsoft LAN Manager, Torus Tapestry, or Apricot’s VXNet.

This thing was big. You can see in the image here that it’s big, but it’s actual dimensions were 2 feet tall, 2 feet front to back, and 16 inches wide. It weighed in at 165 pounds (part of this is likely due to this machine featuring an internal UPS system). There were two handles on the top of this absolute unit of a computer, ostensibly to aid in the generation of work place injuries. There were 8 models at launch, and these were split into two series: 400 or 800. The models per series were 10, 30, 60, and 90. The 400 series all shipped with 4M RAM, while the 800 series had either 8M or 16M. Disk sizes were 157M, 347M, 647M, or 1047M. Cache was either 64K or 128K. Pricing started at $18000 and went up to $40000 (roughly $44000 to $98000 in 2023). This is exactly the kind of machine responsible for killing off the last of the minicomputers. Regardless of model, all VX FT machines came with an Intel 80486 clocked at 25 MHz.

In 1990, Apricot was the 2nd largest PC manufacturer in the UK. They’d done quite well, but again as if receiving knowledge from an oracle, Apricot sensed change. Many manufacturers selling nearly identical machines centered around Intel chips and Microsoft software meant there’d be a race to the bottom. Apricot sold to Mitsubishi for $70 million (about $163 million in 2023).

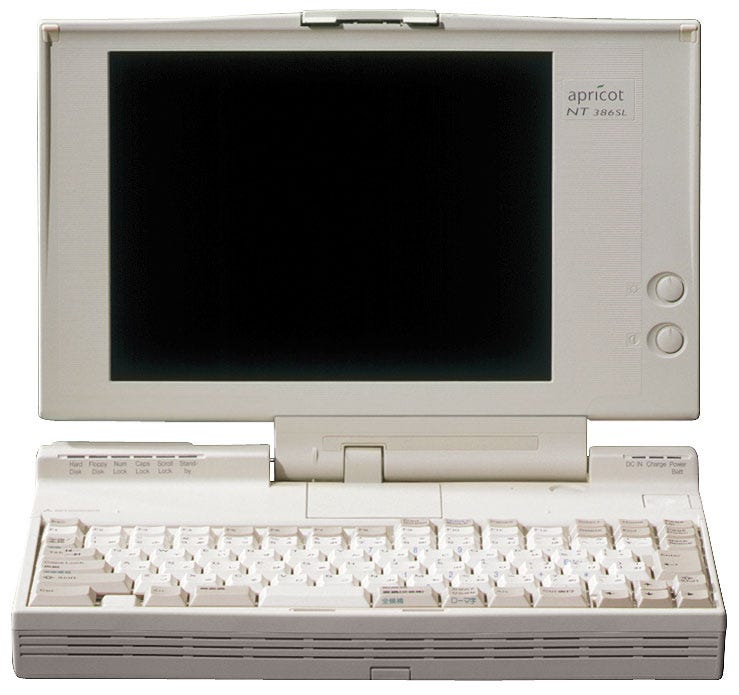

Under Mitsubishi’s ownership, Apricot continued to make and sell IBM compatibles with one notably “Apricot-like” machine being the NT386SL which continued the Apricot tradition of being small, quirky, and innovative.

Most other machines would follow the trends of the time being either mid-towers or desktop machines packing the latest Intel chip into beige boxes with Soundblaster compatible audio, Model-M layout keyboards, and so on. The race to the bottom had enforced such uniformity over time as every manufacturer needed to cut costs wherever possible. Workstations and UNIX servers also sold, but in lower numbers.

In June of 1999, the Glenrothes factory closed, and by October all Apricot operations in Europe were closed. Apricot’s assets were subsequently sold.

ACT/Apricot were innovative, and their designs were unique. The company’s executives seemed to be able to anticipate the future quite well, and they executed on that anticipation quite well. First, the company realized that the end of the mainframe was nigh, then that the end of Victor was close, then that the end of non-IBM-compatible machines was coming, and finally that the end of good profit margins on microcomputer hardware was at hand. Apricot certainly wasn’t alone on that last point; consolidation started in the 1990s and continued through the following decade.