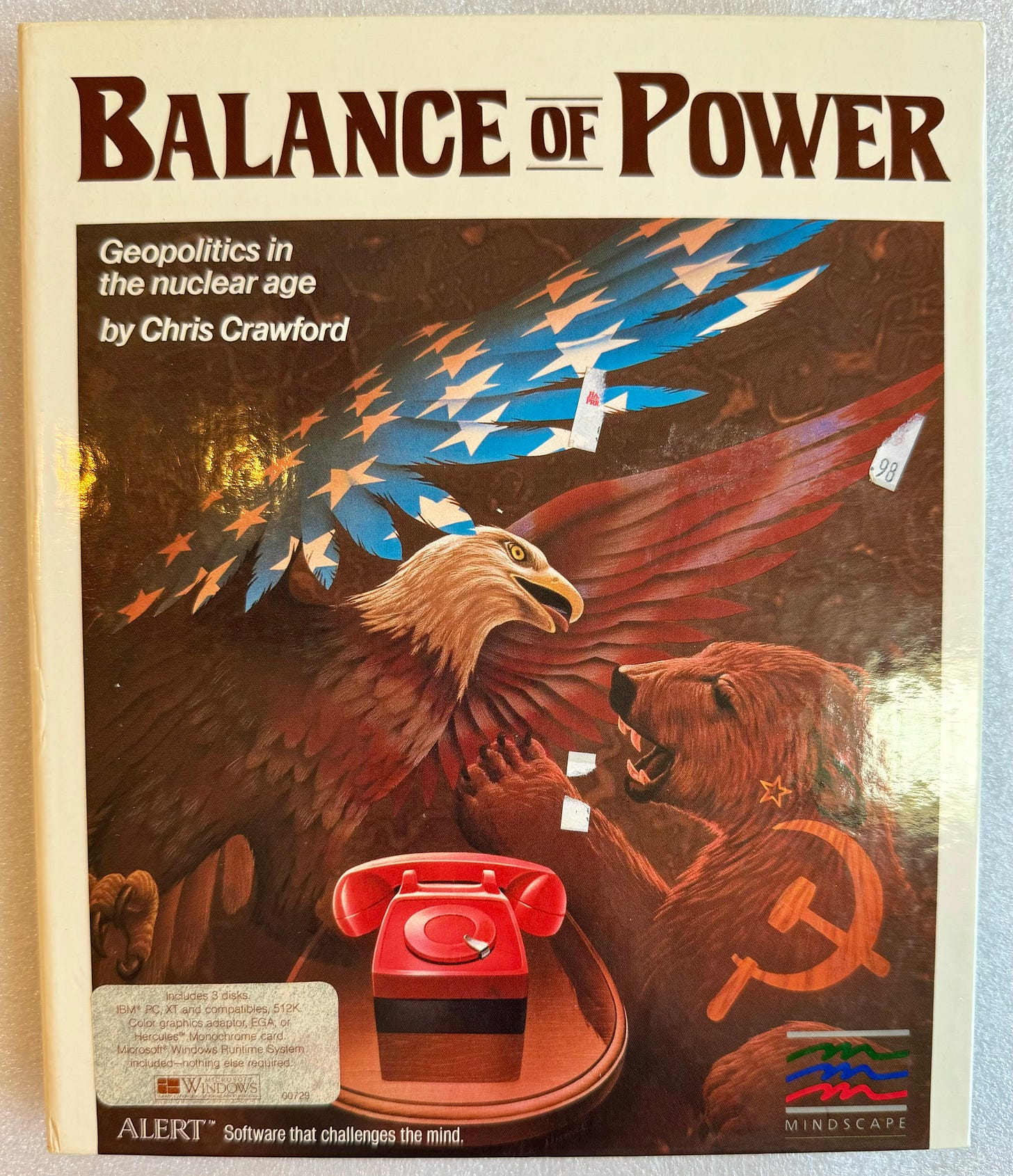

Balance of Power

Have some fun with the end of the world

In 1966, Chris Crawford, who was then sixteen, was introduced to Avalon Hill style wargames by a school friend. Crawford enjoyed the genre of games, but it wasn’t a primary interest of his. This changed in graduate school after a chance encounter with a magazine, Strategy & Tactics. The magazine discussed the history of wargames, and Crawford then began playing wargames more often. His interest in the history of war itself deepened as a result. A few months later, a university colleague told him about a program he was writing that would run a wargame. Crawford had become familiar with computers in his undergraduate physics courses at UC Davis, and he personally doubted that his colleague would have an success in his endeavor. While working on his masters degree in physics at the University of Missouri, he became rather interested in computers as a field of study rather than merely as tools for the study of other subjects. Crawford described his interests in computers, war games, and war history as a consuming passion. Crawford earned his degree in 1975 and took a job teaching at a community college while spending both his free time and that of the school’s IBM 1130 on his passions. Crawford made what was likely the first computerized recreational wargame in December of 1976.

In January of 1977, Crawford purchased a KIM-1. While this was a very limited machine with a 6502 and 1K RAM, it was also just $245 (about $1272 in 2024). It could be connected to a teletype or glass terminal, and it could utilize tape for storage. For Crawford, it was sufficient. He learned the machine’s assembly language, expanded the computer, and wrote a wargame for it.

In September of 1978, Crawford purchased a Commodore PET. The PET wasn’t too different from the KIM-1 in its architecture, but it integrated the most common peripheral components (keyboard, cassette drive, monitor), added some external ports, upped the memory to 4K, and added BASIC and the PETSCII character set. Despite all of those additions making the machine far more capable than a KIM-1, the price of the unit was just $495. For Crawford, this machine was a major improvement, and he ported his game to it. He sold the first copy of his first game, Tanktics, on the 31st of December in 1978. Over the following year, he developed Legionnaire.

Crawford’s early games were simple by his own description, and Crawford was bored with them. He wanted to build a game that dealt with more nuance and involved geopolitics, not just warfare. He undertook such an effort in July of 1979 with a game titled Policy, and he aimed it at PETs with 8K RAM. The bulk of the game was written in BASIC. Shortly after getting the game into a running state, he realized that he’d over weighted resource management in his design and thus the game had developed into tedium. Policy was abandoned after Crawford’s wife took a job in Silicon Valley, and Crawford himself then began working at Atari.

At Atari, Crawford was initially quite limited. The suits marketing professionals felt that any game of complexity was unsalable. This meant that even rather simple wargames were verboten, and something as ambitious as Policy was ridiculous. Then in December of 1981, Alan Kay brought Crawford into the Corporate Research Group at Atari. In this position, he was given not just permission to pursue grand projects, but such was his explicitly stated duty. I can only imagine that this felt like real, tangible, exhilarating freedom for him after two years of what must have been rather depressing restriction. His first big project took eighteen months with the help of Larry Summers and Valerie Atkinson, was based upon the Arthurian legends, and was titled Excalibur.

I did a game at Atari Research called 'Excalibur' about the Arthurian legends. At the time, it was very, very complicated, very involved and so forth and actually still looks better than some of the modern games in terms of its richness and involvement.

— Chris Crawford

In this strategy game, the player takes the role of King Arthur in a Britain that is divided among sixteen kingdoms whose rulers aim to take control of all Britain. Much of the game is spent managing things via menus while the King is in Camelot. There’s Merlin’s room where magic is used to influence rival kingdoms, the treasury which handles taxes and the finances of the army, the throne room where official communications with other kingdoms is done, the round table where the handling of knights is done, and the trap room which is used when under attack. Of course, a game of just this would be rather dull, so the king can move about outside the city. The player can visit vassals or rival kingdoms, and this latter bit will often result in battle. The battle system isn’t very different from that of Legionnaire with a real-time overhead map.

Excalibur was well reviewed and gained some critical acclaim, but it wasn’t all that popular. The most likely reason for the game’s lack of commercial success was timing. The game was released in 1983. The video game crash began that same year and continued through 1985.

By this point, the computer market was changing. Machines were available with far more RAM, disk drives, and more sophisticated video outputs. Crawford set his sites on the Atari 800, 48K RAM, and the 1050 disk drive. The combination of a slightly higher clock, much more RAM, and higher capacities of storage would allow for far more complex software. Something along the lines of Policy was now more easily achievable than it had ever been. On the 16th of March in 1984, Crawford was laid off from Atari and with his job went the idea of a game for the 800.

Rather promptly, he began to work on another game idea, and this time, the target platform was the Apple Macintosh which had been released on the 24th of January that same year. The Macintosh had quite a bit to recommend it: a decently powerful CPU, modest RAM (but far more than what Crawford had previously dealt with), and a crisp display with a GUI. As to the game itself, Crawford sent the following to his agent five weeks after being laid off:

This is...the game that I have been wanting to do for a long time. I propose a game that shows why the USA and the Soviet Union are locked in a dangerous balance of terror. You are the President for the entire 40-year span of the game (1960-2000). All you have to do is get to the turn of the century without igniting Armageddon. It’s not easy. The game is actually about geopolitics, not the arms race per se. You are tied into numerous alliances with small countries the world over. This complex web of obligations is constantly being strained by the petty disputes of the small countries. These small squabbles can erupt into war at any time, and the danger always exists that events could suck you into a major confrontation with the Soviet Union. The central question of the game, then, is to ask how the US and the USSR can carry on a global rivalry without eventually getting themselves into a nuclear war. The answer, of course, is that they can do so only by rigorously constraining and reducing the scope of that conflict.

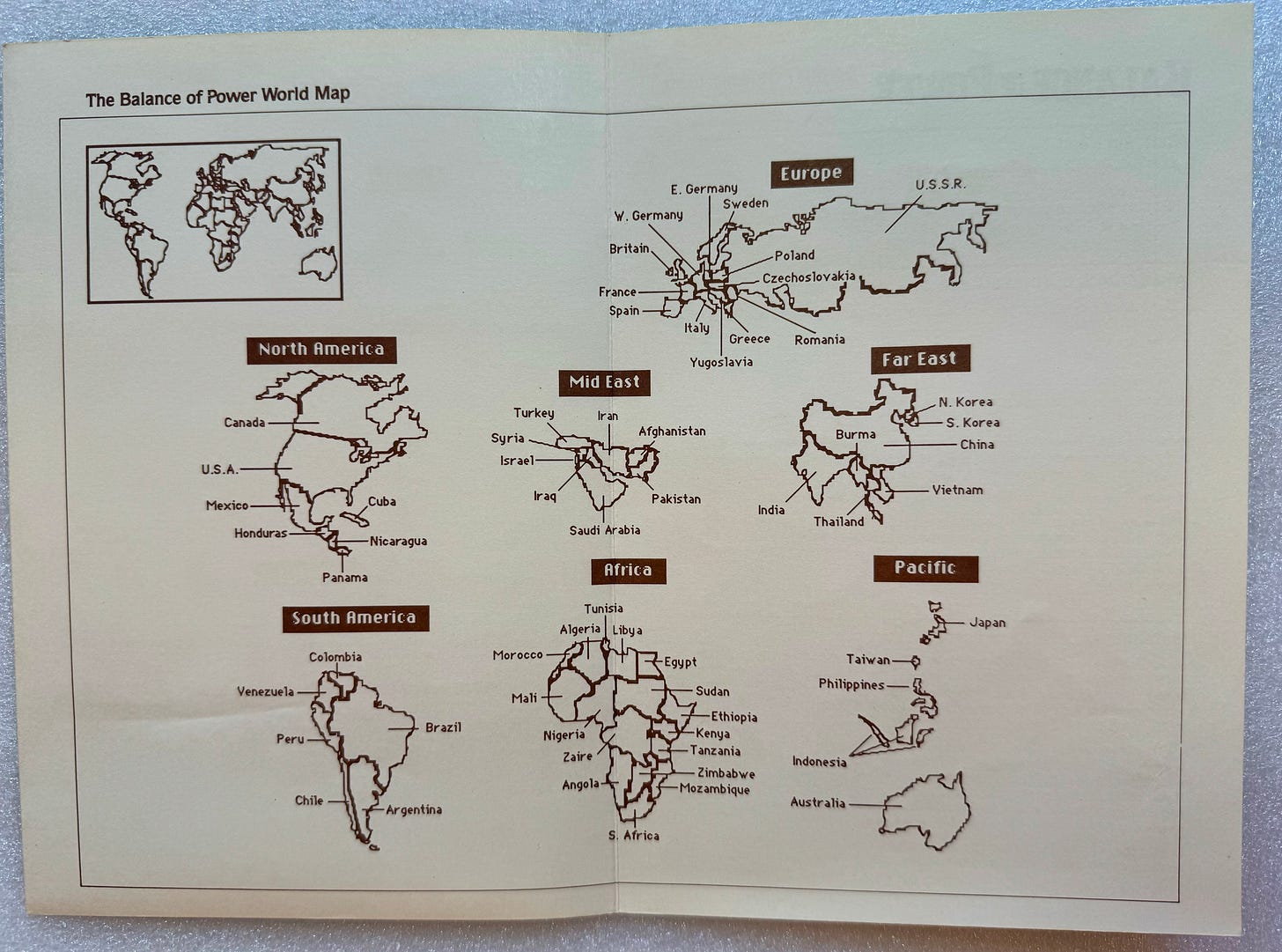

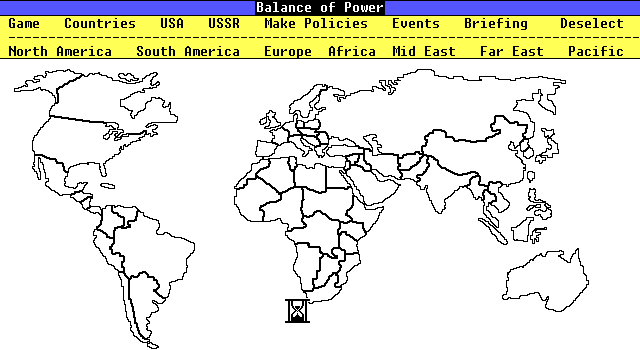

The game would use a smart map that presents a great deal of information about nations and their relationships in graphical format. Icons would show treaty relations, military status, bases, and so forth... I think that this game would grab a great deal of attention.

Still, Crawford considered many more ideas between the time of this letter and the eventual completion of the game. He had wanted to include credibility, moral leadership, resolve, and the like. Many things were considered but very few made the cut. As for the title of this new game, he considered Annihilation of Mankind, The Extension Policy, and Thwarting Armageddon. These were discarded, and he settled on Arms Race.

Arms Race was more complex than a simple wargame. It was a game that involved the politics of the Cold War, and Crawford was more of a war history buff, not foreign affairs. To remedy his knowledge gap, he read every book on the topic that he could get his hands on. In particular, he cites The War Atlas by Kidron and Smith as having influenced the visuals of the game, and he cites The War Trap by Bueno de Mesquita for heavy influence on the theory of the origin of war used in the game. For his general understanding of geopolitics, he cites The White House Years by Kissinger.

The initial release date for the game was the 1st of May in 1985, but as late as July in 1984, no programming work had been done. Additionally, while Crawford had purchased a Macintosh, he had no development tools for the machine. For that, he needed an Apple Lisa. He’d ordered a Lisa in May, but it didn’t arrive until the 1st of August. This meant that all of his notes and designs were on paper, and otherwise, he read Macintosh development manuals and references, wrote some proposals, and continued to collect information. While this allowed him to focus his intentions quite well, there were things that needed to be tested before he could complete his idea.

Quite of a bit of Arms Race was focused on a map of the world. This map was drawn by hand. Initially, Crawford traced it onto graph paper. Then, he redrew the map so that the lines would would match the graph paper’s grid. Finally, he scaled it to make it fit the screen dimensions of the Macintosh. Even the scaling was done largely by hand. He sat down with a tape recorder and a map, read the coordinates for countries aloud “Nigeria. Origin at X = 138, Y = 227. One step north, 1 east, 2 north, 3 east …” then typed those values in to his computer. After that, he wrote a program that would convert those values for the map, and adjust the digitized map as appropriate.

It was as late as October when Crawford realized the game was too large for the Macintosh’s RAM. To slim it down, he completely removed trade as a game element. The game was working with many features of the final product included by the middle of November.

To my eyes, many years later, the course of events up to this point and after seems preordained, but I imagine that Crawford was extremely stressed. The gaming world was in a free fall collapse and the publishers with whom he’d intended to release his game no longer existed. He was staring down financial insolvency, and no extant publishers were biting on the proposal. Jim Warren, the founder of the West Coast Computer Faire, learned of the game through some of his friends and invited Crawford to his home in the mountains near Santa Cruz. The two spoke about Crawford’s game and his financial difficulties, and Warren convinced him to continue working. Warren was right to urge Crawford on as Random House expressed interest in the game before that Thanksgiving. Their editors did good work, made great recommendations, and Crawford dutifully implemented their changes. The game was now better than what Crawford had intended, and he tried to push it. He delivered the game to them in May of 1985 with an ultimatum that they accept this version as an alpha or drop the contract. Random House then dropped the contract.

Well, Crawford was now in debt to Random House, and once again on the brink of bankruptcy. This pushed him to start looking for employment, but he also chose to start sending the game to play testers. The feedback he received was valuable and largely unanimous: it’s too hard. This pushed him to reduce non-superpower countries to passive entities. The user could now only play as either the President of the United States of America or as the General Secretary of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. The game world was simply bipolar instead of multipolar.

Shortly after but still in that May, Crawford’s perseverance paid off. In March he’d spoken at a local meeting of the Macintosh Special Interest Group of the Software Entrepreneurs Forum. While it was a small group, one of the people in attendance was Steve Jasik. Jasik was a coordinator for the Berkeley Macintosh Users Group, and he asked Crawford to speak at their meeting in May of 1985. At that meeting was Tom Maremaa who was a reporter for InfoWorld. Maremaa subsequently interviewed Crawford and published an article about the game in the InfoWorld issue for the 10th of June in 1985.

This article in InfoWorld was seen by someone over at Mindscape, and this resulted in a contract. A few days after an agreement was reached, Crawford met with the Mindscape team in Chicago. That first meeting was run by Sandy Schneider, and it lasted about six hours. The Mindscape team had a list of concerns they brought to the meeting, and each concern was addressed one by one. Nothing on that list was given any time, and each item on the list was discussed and set aside within a matter of minutes. From Crawford’s description of this meeting, I get the impression of ruthless efficiency within Mindscape at the time. One of the changes was the name. Roger Buoy suggested the title Balance of Power. Crawford saw this as being a far better name than any other, and he chose to use it.

The majority of the changes were a matter of refinement. The interface was made a bit simpler, accidental nuclear war was made less probable, bugs were ironed out. A new beta was sent on the 1st of August in 1985. As one might expect, the testing was thorough. The game was released in late September of 1985 to much acclaim. On the 19th of December in 1985, The New York Times Magazine ran an article titled Playing with Apocalypse by David Aaron, Deputy Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs during the Carter administration. The article began:

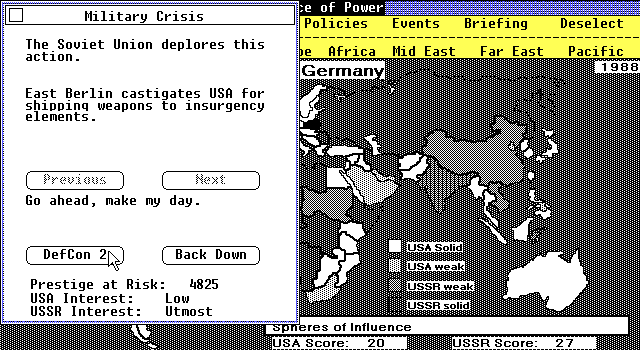

THE DAY STARTED like most days at the National Security Council. I first scanned the intelligence reports for any urgent items: coups d'etat, major military actions, unexpected crises. Next, I searched for odd signs and portents, the cloud on the horizon. There it was: Russian military advisers were being sent to Argentina - our hemisphere, our sphere of influence. The act had to be challenged. The Soviet reply was swift and unsatisfactory. A stiff response was essential. In the next move, I blew up the world.

That was discouraging. Granted, this was no video-arcade whiz-bang-beep affair. It was Balance of Power, the most sophisticated strategic simulation in America, other than Pentagon war games. And it was only my first try.

Toward the end of Aaron’s article comes something that isn’t all that surprising for those who were alive during the height of the Cold War, but it will be shocking to those who’ve not studied the topic or lived through it. Aaron spoke with Crawford and added some of the dialog to his article:

“One of the things that bothers me is that a great many people who are deeply concerned about nuclear war don't see the connection with international politics,” Crawford said. “Nuclear war is this ogre out to eat up the world. When you take that approach, you absolve yourself of responsibility. I insisted with the publishers on responsibility. If nuclear war happens - you make it happen.” Crawford's greatest frustration was having to simplify the game. Originally, in addition to prestige, Balance of Power had three other scores: human rights, material well-being and total deaths. (It could count up one billion fatalities a game, and that was short of nuclear war.) “Everybody hated it,” he said. “People did not want to test their own values. They wanted me and the computer to tell them what was right and wrong, so I had to cut it out.”

I assured him that dropping deaths did not hurt the game's realism; never, in all my years on the National Security Council, had I heard the total number of fatalities discussed as a policy consideration. The closest anyone ever came was Warren Christopher, Deputy Secretary of State, during the Iranian-hostage rescue effort, who asked how many hostages might be killed. Nobody cared how many Iranians would die.

Ultimately, Aaron did praise the game, and he stated that he kept replaying it. He clearly liked it. He had a few things to say about the realism of it. He praised how close it got to the real thing, but he did note points where it drifted off a bit. To better give you an idea of just how well received this game was more generally, Ezra Shapiro at BYTE wrote the following in the issue for March of 1986:

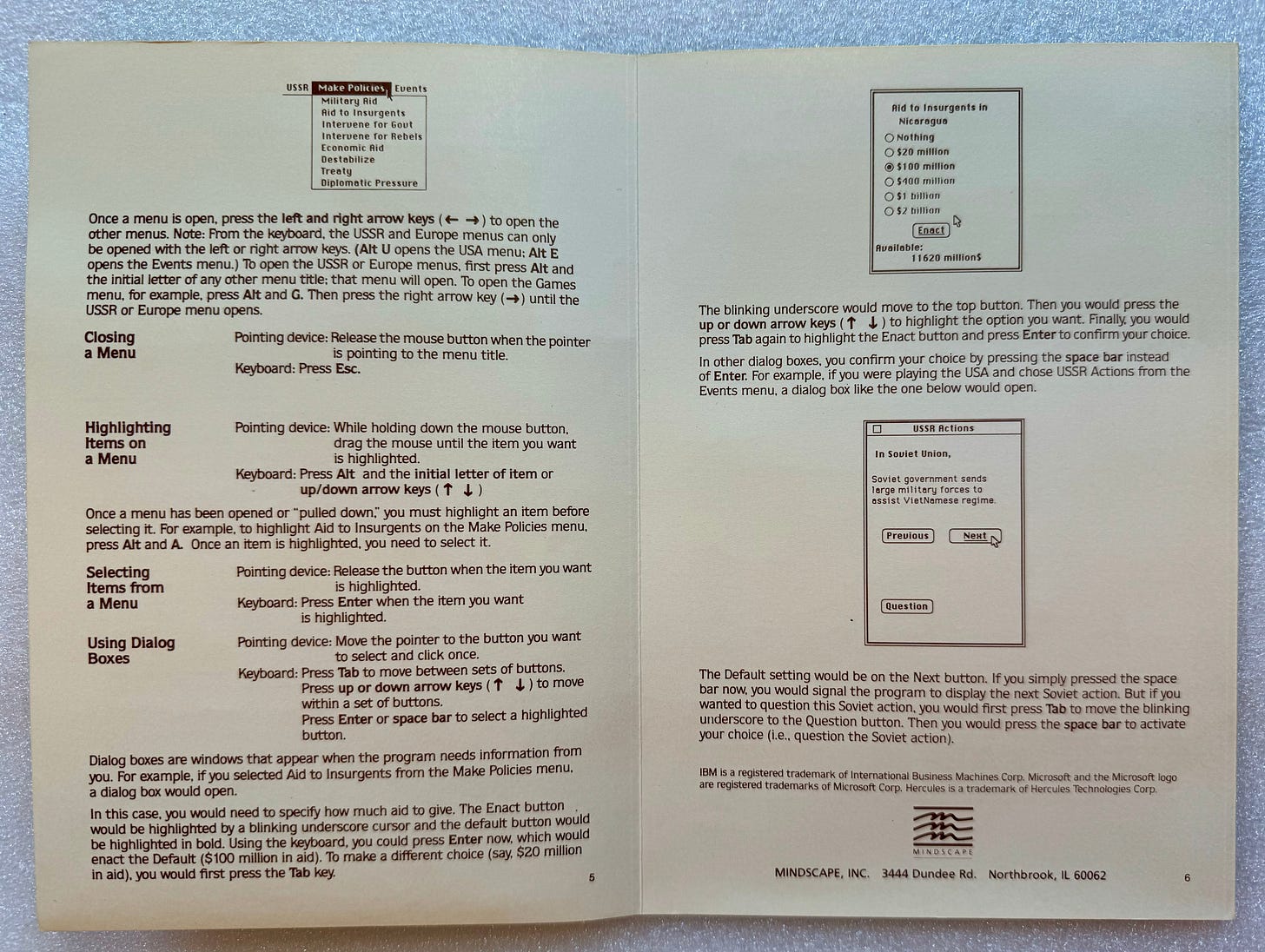

… Ostensibly a game for the Macintosh, this simulation is one of the finest programs -of any type- that I’ve seen on a microcomputer. Subtitled “Geopo litics in the Nuclear Age,” the game is an exploration of superpower diplomacy played on a world map. You choose to be either the US or the USSR (In a one-player game, the computer takes the other side. You can also play against a friend.) In brief, you decide whether to support or undermine the governments of each of 60 countries; you can send economic or military aid to either government or rebel forces, conduct covert operations to destabilize unfriendly regimes, apply diplomatic pressure, sign treaties, station troops. The object is to increase your sphere of influence and international prestige-at your opponent's expense-while avoiding nuclear war, in which both sides lose. The dynamics of the game consist of challenging your opponent's moves; at every step the other side takes you can choose to send a diplomatic protest, which can expand into a full-scale crisis. Your opponent has the same opportunity. It's a grand global game of "chicken," played for the highest stakes possible.

I don't have the space to get much further into a discussion of how the game is played. It's an intriguing adult simulation, provocative as well as entertaining. A carefully thought-out game could take days, and, as an educational tool. I could see Balance of Power as a month-long project for a high school social science class. But what strikes me most forcefully about the game is how beautifully it uses the Macintosh's resources. You can display vast amounts of political, social, economic, and military data about the world, ranked in several ways, on cross-hatched maps. Every “event” triggers changes in status reports, maps, and mock newspaper displays. And the algorithms for analyzing the progress of the world situation over the course of a game's eight-year span are very complex. Limitations? My mouse arm gets tired. I wish the Mac allowed more keyboard shortcuts. And I suppose someone with a Ph.D. in political science could take issue with the game's content. But as Chris Crawford, the game's designer, points out in the comprehensive manual, as long as you're asking questions about the realism of Balance of Power, it still has something to teach you.

If I gave out little stars or little disks for computer programs, this one would get the highest rating. This is what computers should do.

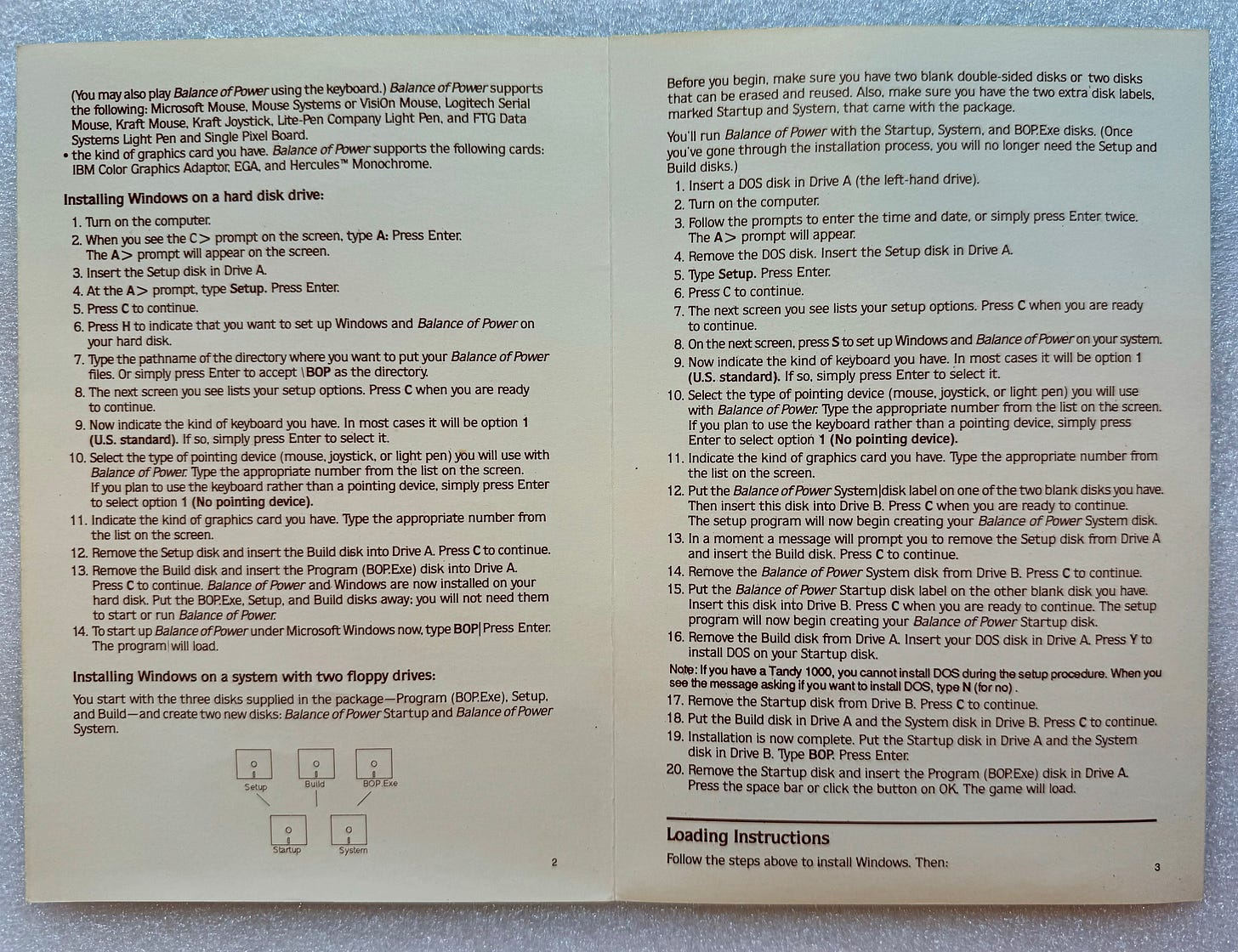

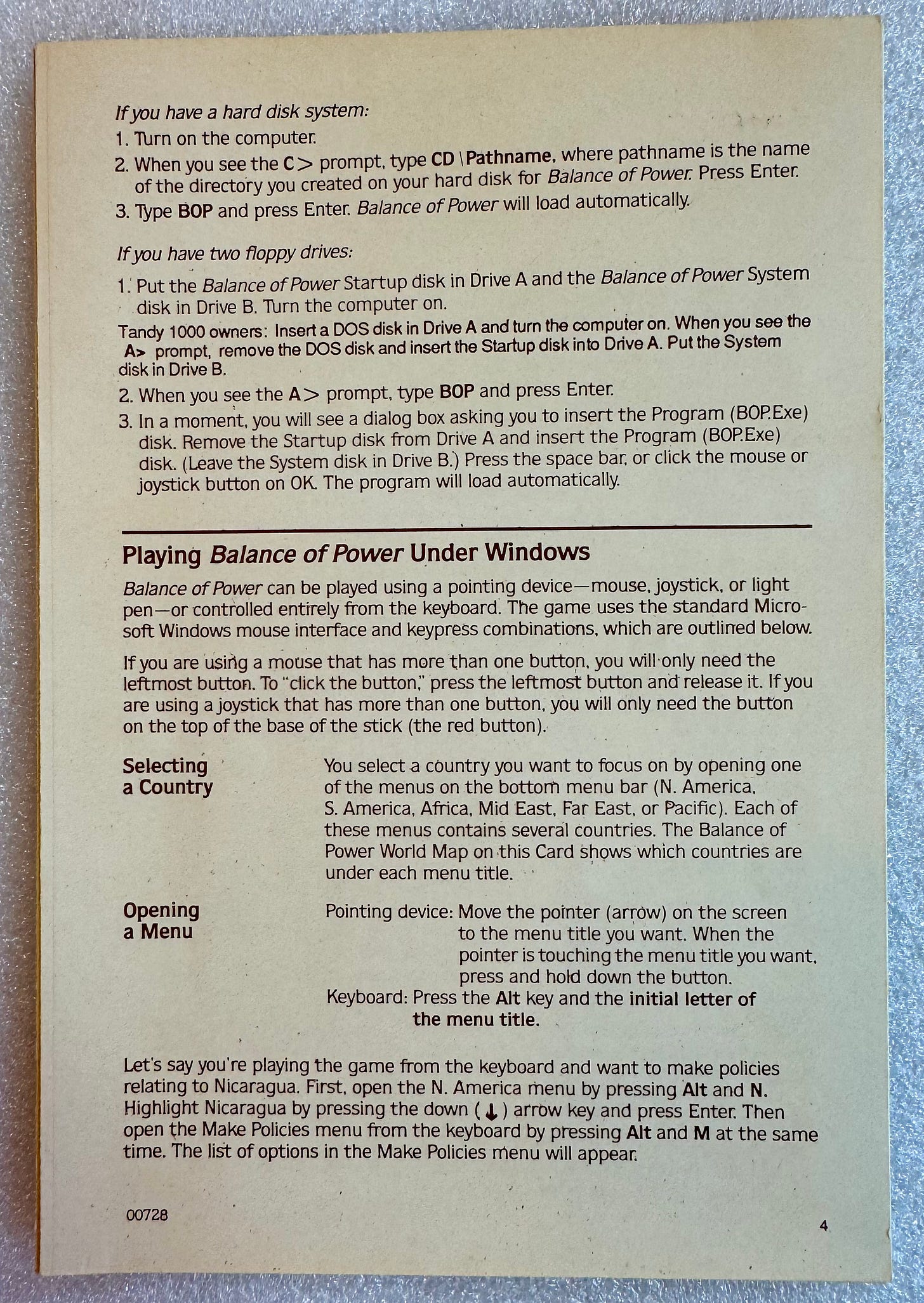

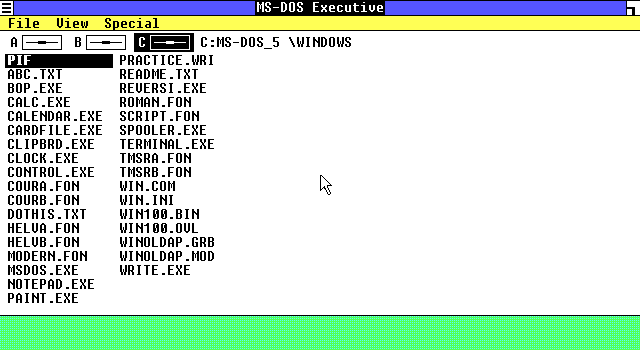

Balance of Power was a hit on the Macintosh. The first port was to the IBM PC and compatibles in 1986 where Balance of the Power became one of the first programs for Windows, and the first third party video game ever created for Windows. Being available on the Macintosh and PC, the game became a multiplatform best seller. A port to the Amiga was made available shortly after in 1986. The Atari ST and Apple II received ports in 1987. The MSX and PC-98 ports were made in 1988.

In the December 1986 issue of BYTE, Ezra Shapiro commented on the PC port. She noted that it was among the first programs to make use of Windows, and then that those who already owned Windows had a shorter installation procedure. While still loving the game, she stated that it wasn’t quite as nice as the Macintosh version, and she said further that while the PC she used for testing the port had four times the RAM, the game seemed no faster than the original Macintosh version. Still, the conclusion read: “If you’ve got an MS-DOS machine and a Macintosh, buy the Mac version of BOP. But by all means, get the program.”

Even after the ports and quite some time on shelves, more press about the game kept coming. Compute! in May of 1988 had two different bits about the game. The first by Gregg Keizer was brief. In the article Our Favorite GAMES, he wrote of Balance of Power:

Go eyeball to eyeball with the Soviets (or with the Americans) and see who blinks first. Mindscape’s Balance of Power, the game that made Chris Crawford famous, is an impressive recreation of the world’s geopolitical landscape as viewed from one of the two superpowers. You desperately try to avoid nuclear conflagration as you advance your own ideology. With tools like money, guns, troops, treaties, diplomatic pressure, and dirty tricks, you coax third world nations to your side. All the while you’re putting the pressure on the Soviets and their clients. Crisis management is the key to winning. Back down at the wrong time and you’ll lose the game. Call one to many bluffs and you’ll see the chilling message You have ignited a nuclear war.

The second was written by none other than Orson Scott Card. This was the only review by a well-known name that seems to have been negative (at least that I could find). He wrote:

Compare President Elect with a beautifully designed game like Balance of Power, though, and you begin to realize that while bad design can be annoying, bad history makes a game unplayable.

Further down, he says:

…you very quickly realize that the shadow is really Chris Crawford, leaning over your shoulder and bullying you into playing the game his way.

Ultimately, Card states that Balance of Power is a propaganda piece, but also adds that Crawford is the best designer of simulation games that he’s seen.

Of course, dear reader, this is ARF. You knew I’d probably reference BYTE, and you knew that I’d likely have to take a look at the PC port. Afterall, we’re talking about one of the earliest Windows applications as well as the first (third party) Windows game. For me, this is irresistible no matter the views of Orson Scott Card.

This is an excellent game. Of course, I rather enjoy strategy games and simulations. For those who don’t, it is still worth a cursory examination as an historical artifact. Balance of Power has become a time capsule that preserves the mindset of an era of global tension, and the worst and deepest fears of multiple generations of human beings. It is also a bit of software that demonstrates some of the capabilities of Windows 1, how complex an application could be and still be usable on an 8088 (though I do recommend at least an NEC V20 @ 8MHz or better), and just how wrong some of the early marketing folks at Atari were. People are clearly willing to play complex games.