The History of Commodore, Part 4

The Amiga, The Decline, The Fall

This is part four of a series on Commodore. If you haven’t already, you may be interested in reading part 1, which covers the creation of the 6502, the founding of MOS and Commodore, and the circumstances that led to the creation of the first Commodore computers. Part 2 covers the Commodore VIC-20, and Part 3 cover the Commodore 64.

Jay Miner was born on the 31st of May in 1932 in Prescott, Arizona, and he became interested in electronics at an early age. After grade school, Miner enrolled at San Diego State. He wasn’t long to remain there as the Korean War was in swing. Miner chose to join the Coast Guard. He then attended an electronics school in Groton, Connecticut. He married his wife Caroline Poplawski in 1952, and Miner and his wife moved to California where Miner attended UC Berkeley from which he graduated in 1958 with a degree in electrical engineering.

Following his graduation, Miner worked at several startups and this suited him. He wasn’t one for bureaucracy, and he preferred to work in environments where people simply did what needed to be done. Harold Lee of Atari then hired Miner. At Atari, Miner became the lead chip designer for the VCS, the 400, and the 800. With these machines out the door, Miner wanted to tackle something more ambitious. He wanted to create a computer centered on a sixteen bit CPU and a floppy drive. These would make development work in general far easier, and more importantly to Miner, it would be easier to do development for the machine from the machine itself. The Atari executives didn’t wish to damage sales for the VCS or the 400/800 systems, and Miner was explicitly told no. This wasn’t unique to Miner’s project. Atari didn’t want to hurt VCS sales and therefore didn’t market the gaming potential of the 400/800 machines either. Miner left Atari in 1982 for a company called Zimast that was working on chips for pacemakers as he knew the guy who started it. Miner was given stock in the company, and it looked to him like a rather interesting startup.

Around this same time, a group of software developers at Atari were asking for a pay raise. This wasn’t an unreasonable request as the company was making money hand over fist. Atari said no, so the group of developers left and started Activision. One of those programmers was Larry Kaplan. He was somewhat unhappy at the new company, and he called Miner. During the conversation, Kaplan suggested that they form their own company with Kaplan handling software and Miner handling hardware. Miner agreed and he suggested that they get some outside financing. They hired a company on Scott Boulevard in Santa Clara, and that company found a Texas oil guy and three dentists who were all looking for a new investment in that space. This wasn’t too difficult given that at this time video games were in the midst of a large bubble. The thought was that the new company would write some games for and make peripherals for the Atari 2600, but also work on a project that would be the best game machine possible, and they’d license it to Atari. The company name became Hi Toro because it sounded high tech and Texan. Miner and Kaplan were both technical people, and both they and the investors knew that they’d require someone with management experience. For this, they turned to David Morse from Tonka Toys. They then located an office in Santa Clara, California and they began the work with $7 million (around $22 million in 2023) in funds. They launched some successful products and this provided even more money for the game machine project now named Lorraine after Morse’s wife. Nolan Bushnell, however, was wasn’t happy to have lost Kaplan and gave him a very generous offer to return to Atari. With Kapaln’s departure, Miner became the VP of product development and Morse was the President. At some point, the investors became aware that Toro was already a company name. The investors and Morse then went back to the drawing board. They wanted something that sounded friendly, was short, was in some way reminiscent of Atari, and was also memorable. The name they chose was Amiga. So it was that in Santa Clara, California in the middle of 1982, the Amiga Corporation was founded by Jay Miner and David Morse with the goal of creating the world’s greatest games machine.

Or, rather, that was Morse’s goal. Miner was still intent on making a computer based around the Motorola 68K and a floppy drive. He wanted to make the best home computer possible at the time, and by 1982 he felt that this machine should be capable of running a flight simulator. These two visions were not necessarily fully incompatible, but they did create serious tensions. The video game console idea required cost reductions wherever possible. Miner wanted the machine to have expansion slots, and was told no. Expansion slots were around fifty cents a piece at the time, and they’d also require a large casing. After serious debate, he managed to get them to concede to a single internal expansion slot. Miner wanted 512K RAM as standard. He was told no as RAM was quite expensive, and so the amount was reduced to 256K. He encountered similar opposition around hard disks and floppy drives. These required a larger and more expensive casing as well as expensive connectors and controllers.

In 1983, the video game market imploded. The market had been flooded with games of rather poor quality and sales rapidly declined. Seeing this happen, the fledgling company quickly changed its tune. Miner was given the go-ahead on the inclusion of a floppy disk drive and on RAM expandability. Lorraine was now the only true hope for the new company. The company’s peripherals like the PowerStick and JoyBoard were now moribund with no gaming market to support them. With the game market crash and a machine whose requirements were still taking shape, a rather ambitious deadline was set: CES in January of 1984.

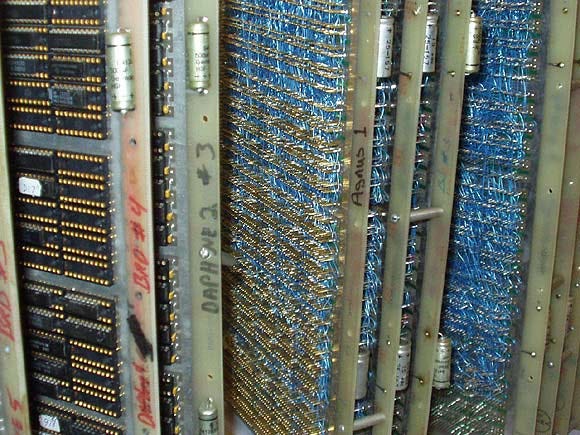

The company culture was very… laid back? Miner brought his dog Mitchy to work every single day. She was cockapoo, and she went from desk to desk saying hello to everyone, getting affection, and sometimes getting treats. Her presence helped set the tone of the workplace, and got everyone to be a bit more relaxed. People there were often a bit weird showing up in purple tights and pink bunny slippers, or looking like something akin to a homeless hippy with long hair. What Amiga cared about was that the job got done and they didn’t much mind how. Apparently, wiffle bats were frequently used in the settling of debates and arguments. In designing and building Lorraine, this motley team of fifteen to twenty people used breadboard. There were three custom chips and each of these required eight breadboards a piece, each of which was roughly three feet by one and a half feet. These were then arranged vertically in a circle with each board being a spoke in a sort of wheel, and the wires could then be run where an axle might have gone. Each board held about three hundred logic chips, so about seventy two hundred total, and a number of wires that today perhaps only Steve Chamberlain can truly appreciate.

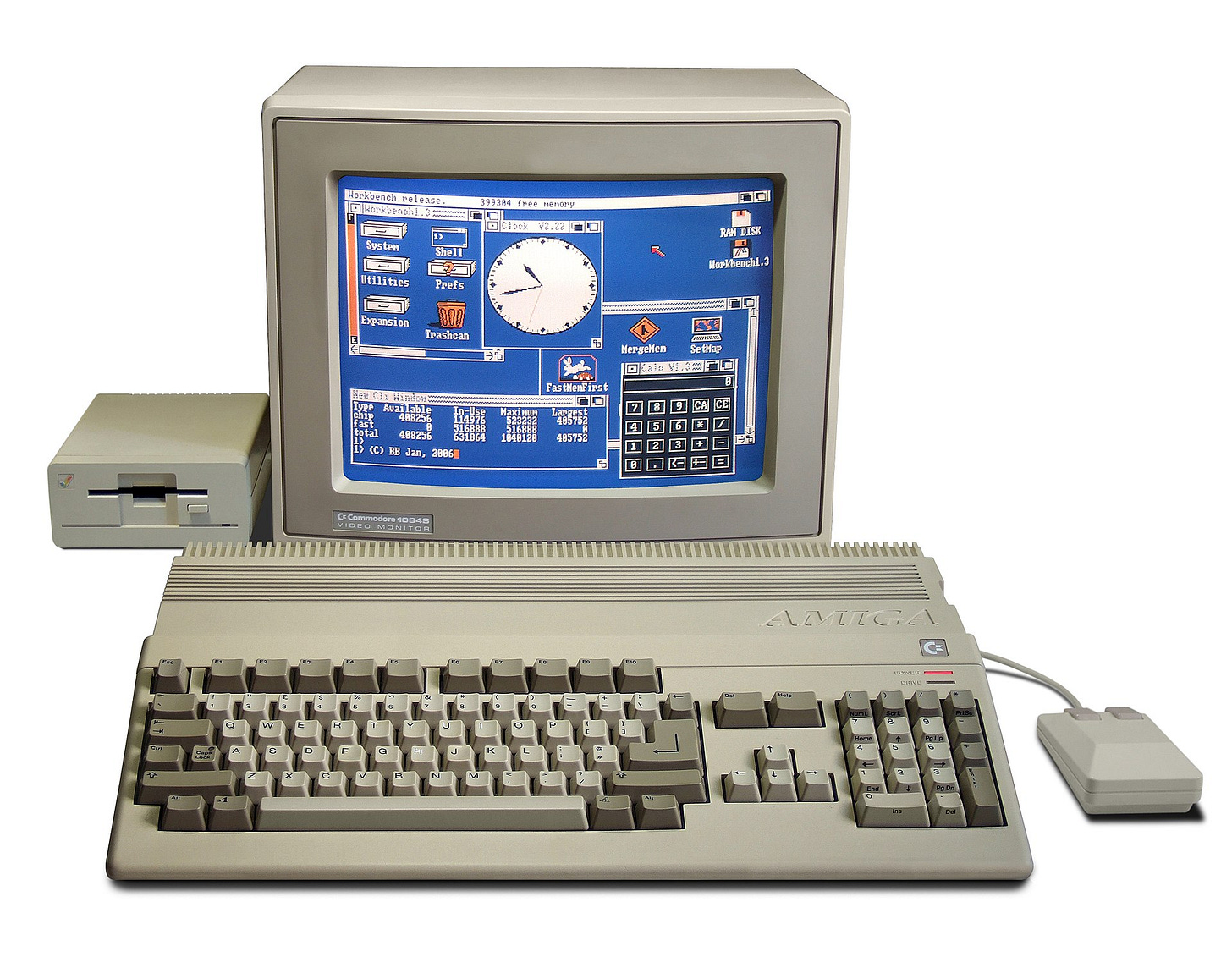

The software for this machine was being worked on by RJ Mical and Dale Luck. The operating system for Lorraine was truly ambitious for the time, and it was unmatched in the home computer world. According to Miner, the operating system was truly the best feature of the system. In just 256K, it delivered a fully preemptive, multitasking, operating system with priority based scheduling and interprocess communication. This was a GUI system with windows that could have their own color palettes, their own resolutions, and so on. This was built of three main pieces: AmigaDOS, Intuition, and Workbench. AmigaDOS, as the name implies, was responsible for hardware abstraction and disk operations. Intuition was the windowing system API, and Workbench was comprised of the desktop environment and file manager. The kernel, called Exec, was the brainchild of Carl Sassenrath who was hired to work on the OS and this was expressly what he wanted to do from the start. In his interview for the job when asked what he wanted to work on he stated that he wanted to make a multitasking OS. Amiga obliged. This system was booted by Kickstart. Which was the bootstrap loader for the system. In the first model, this was done off a floppy disk as Amiga wanted to be able to ship updates to correct any bugs. In later models, this was on a ROM chip.

Neither the final hardware nor the final software were completed in time for CES. Mical and Dave Needle (a chip architect who worked with Miner) took all of the breadboards to the show in a large box. This box was large enough that the two purchased Lorraine her own ticket for the trip. During the flight, a meal was served and the duo tried to get more food by putting a pillow and jacket on Lorraine and asking the stewardess to provide “Joe Pillow” a meal. Mical and Luck had also written several demo programs to show off the hardware. The most popular and most impressive of these demos was the “Boing Ball,” a simple demonstration of a red and white checkered ball bouncing around a screen with synchronized audio (the boing sound was actually Bob Parasseau hitting the metal overhead door at the back of the office with a wiffle bat). The machine was well received at CES. Unfortunately, the company had exhausted its funds, but rather fortunately, Atari provided a $500000 dollar advance (around $1.5 million in 2023) on the licensing deal to keep things afloat. Shortly after this advance was made, Jack Tramiel, the former Commodore boss, approached Amiga to purchase the company for ninety eight cents per share. Amiga refused. Morse began looking for other buyers, and he settled on Commodore. Commodore not only wanted buy the shares of the company but also pay off the loan to Atari and end their obligations to them.

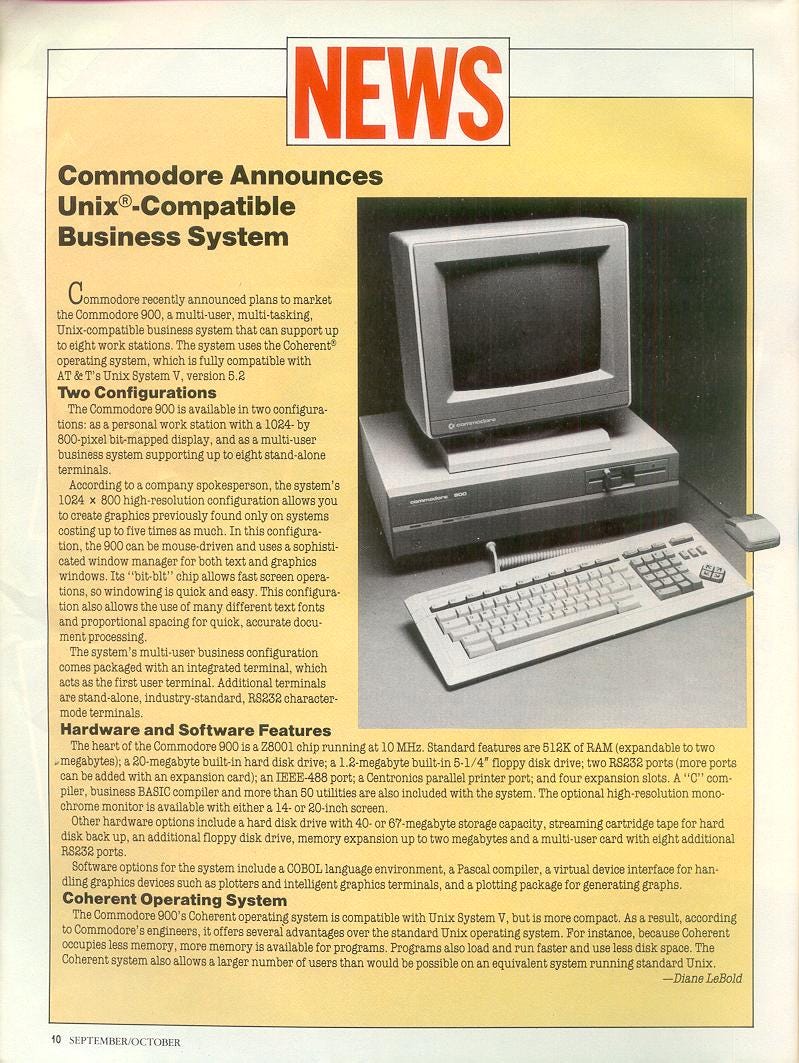

With Tramiel having left Commodore, Commodore was going in many directions at once. 1984 saw the company introduce the 264 series (similar to the plus 4, but with the 7501 clocked at 1.76MHz) with very poor reception and bad sales numbers. The 500, 600, and 700 series machines, which were intended to be the new line of CBM machines, were likewise poor market performers. Commodore’s best machines at this point were the Commodore 64, the Commodore Colt (PC clone), and the CBM 900 (a UNIX machine).

While Commodore was struggling, Tramiel purchased Atari from Warner Communications. He didn’t want his new company to expand its eight bit line, and he was searching for technology to acquire. While sorting through his newly acquired assets, he discovered the exclusive licensing deal of Amiga technology to Atari. Commodore was suing Tramiel for interference in their negotiations with Amiga, and Tramiel was suing Amiga for breach of contract on the 13th of August in 1984. Amiga asked Commodore for help, and Commodore then proceeded to purchase Amiga for four dollars twenty five cents per share (totaling around $24 million [or around $76.5 million in 2023]), and paid off one million in debts that Amiga had accrued. Having lost the quest to acquire Amiga, Tramiel went on with Atari create the Atari ST line of computers.

Lorraine was finalized into what we now know as the Amiga 1000 which was unveiled on the 23rd of July in 1985 at New York’s Lincoln Centre by Thomas Rattigan. Andy Warhol was present and used the machine to create a picture of Blondie’s lead singer Debbie Harry (also present) while music made by Roger Powell and Mike Boom was heard.

With Commodore’s poor sales on everything but the Commodore 64, the purchase of Amiga, the Tramiel lawsuits, and the price war reducing the 64’s profit margin, Commodore was hurting. This delayed volume production of the Amiga significantly, and by October of 1985 only fifty Amigas existed and these were used for demos and software development by Commodore itself with a few going to trade press. Adding insult to injury, Tramiel had managed to get his ST on the market and was taking orders ahead of Commodore, and it was selling for half the price of the Amiga. This was possible due to the ST using off-the-shelf components and GEM by Digital Research. The Amiga 1000 was finally on store shelves by the middle of November in 1985, but it didn’t follow Commodore’s usual playbook. The executive team felt that the Amiga shouldn’t be sold Sears, K-mart, or hardware stores. This was a serious business computer that needed to be sold in serious business computer places. This was further hurt by a lack of decent advertising. Many within the company felt that the machine’s clear superiority would sell itself. This isn’t true. Never underestimate marketing.

For those who did purchase an A1000, they got quite a bit. This was a machine that featured a Motorola 68000 clocked at 7.16 MHz. The 68K had a thirty two bit internal data path and registers but utilized a sixteen bit external databus. It had 256K RAM that was expandable to 512K with a first party dedicated cartridge, and up to 8.5MB via external expansion. It had an 8KB bootsrap ROM with 256K of write-once memory (populated by the Kickstart floppy at power-on). The Amiga 1000 had a four thousand ninety six color palette and could display thirty two, sixty four, or all four thousand ninety six colors at one time depending upon the mode. The machine had four audio channels of eight bits each (or two stereo channels) at a sampling rate of 28kHz. The machine featured a single three and a half inch, double sided, floppy disk drive at 880K in one hundred sixty tracks of eleven 512 byte sectors each, and the machine was capable of reading an entire track at a time. It had analog RGB out, RF out, and composite out. Audio could be sent over RCA output or over the RF modulator. For inputs, the Amiga 1000 featured RJ10 for the keyboard, two DE9 ports for joysticks or mouse, an RS-232 serial port, a parallel port, and a port for a second floppy disk drive. There was also an eighty six pin expansion port. Along with the Amiga operating system, the A1000 shipped with AmigaBASIC and a speech synthesis software package from Softvoice. This base configuration sold for $1295 (around $3700 in 2023). A companion RGB monitor was another $300 (around $857 in 2023).

All of the impressive capabilities with just 256K RAM were made possible by unique chips made just for the Amiga. These were Agnus, Denise, and Paula. These names weren’t randomly chosen, but were representative of their primary functions. The ag in Agnus was due to its use in address generation, the d of Denise was due to its in use in display data, and the p of Paula was meant for ports (audio).

Agnus controlled all access to RAM from both the 68000 and the other chips in the chipset using a priority system. It included a blitter and a copper. The term blitter comes from “Block Transfer.” It’s a kind of coprocessor that can access memory and transfer memory on its own. It can also combine color images, do polygon fills, draw lines, and do multidimensional array multiplication. It can do this work while the CPU is doing other work completely independently of the blitter. This is obviously useful in games, but the blitter was also useful in window handling, simulations, and other tasks. The copper was a video-synchronized coprocessor. In the A1000, the Agnus was capable of addressing 512K RAM, but later models increased this and those models were referred to as “fat Agnus” and naturally the “fatter Agnus.”

Denise was the main video processor. In standard video modes, Denise was capable of generating a display that was either three hundred twenty or six hundred forty pixels wide by either two hundred or two hundred fifty six pixels tall. Vertical resolution could be doubled via interlacing. Denise also supported eight sprites, which while useful in gaming were also useful for things like a mouse pointer. Denise handled the mouse and joystick inputs too. This chip made use of planar bitmap graphics where the bits per pixel were split into separate areas of memory called bitplanes. There were five such planes yielding thirty two colors selected from a palette of four thousand ninety six. A sixth plane was available for two extra video modes: halfbrite, and hold-and-modify (HAM). Each of the color bitplanes had its own pointer to the location of that bitplane in memory which could be selected from anywhere in memory, so each bitplane (representing colors in pixels on screen) could be exchanged by changing values in pointer registers without reading/writing display memory.

Paula was the audio chip with four independent, hardware-mixed channels of eight bits each supporting sixty five volume levels. These audio channels were not synthesizers, but rather digital waveform players. Waveform synthesis could be done by the CPU offline and then waveforms (notes) could be placed in memory. These waveforms could represent any instrument and needn’t have been created by the CPU. They could also be digitized off of live instruments. Each channel had its own controller that read memory and sent the audio out. Each controller had its own dedicated, independent, high priority DMA time slot preventing interference. The channel controller could read waveforms as long as 68K from memory on its own, or with help from the CPU, it could read any length. The processor only told the controllers where to look, but the channel controllers handled everything else. Paula also handled interrupts and I/O functions like the serial port and floppy drive.

BYTE magazine closed out their preview of the Amiga (which was their cover for the issue) in August of 1985 with the following:

We were impressed by the Amiga’s detail and speed of the color graphics and by the quality of its sound system. The interlocking features of the Amiga - its custom chips, multitasking support, multiple DMA channels, shared system bus, display-drive coprocessor, system routines in ROM, etc. - point to a complexity of hardware design that we have not seen before in personal computers. (It’s interesting to note that the Macintosh’s complexity is in its software and that according to several third-party developers who have used both computers, the Macintosh is harder to program.) The synergistic effect of these features accounts for the speed, quality, and low cost of the Amiga. We are also very excited about the inclusion of the text-to-speech library in the Amiga. This means that any Amiga program can potentially create voice output, something that has never been common in personal computers because it was never, until now, a standard feature. The hardware looks good - we have seen it work - but we saw very little software actually working (a painting program, the Workbench “desktop” and a few demonstration programs). However, we think this machine will be a great success; if that happens the Amiga will probably have a great effect on other personal computer companies and the industry in general.

Miner was then interviewed in the November issue of BYTE about the custom chips he created, and the Amiga featured heavily in the September 1989 issue about 68000 family and all of the Amiga’s animation capabilities. Also in that issue, Adam Brooks Webber compared the Macintosh and the Amiga. The Amiga won his praise for the user interface, but lost in the graphics primitives. The Amiga then won on devices, multitasking, and memory management. Webber summarized the comparison with the following:

Both of the 68000-based machines have excellent system software in places, but the Amiga is the winner in five of my six areas of comparison. The Amiga software is a bit thin: For example, it could use a more complete set of graphics primitives. But the Amiga’s shortcomings are minor in comparison with some of the Macintosh’s deep-rooted problems. The Macintosh lacks multitasking but tries to fake it, and it insists on a complicated user interface but leaves much of the work up to the application. These are serious drawbacks, and it is difficult to imagine elegant repairs for them.

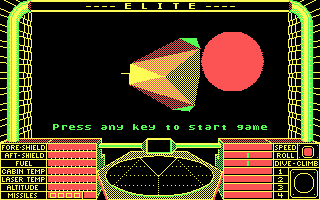

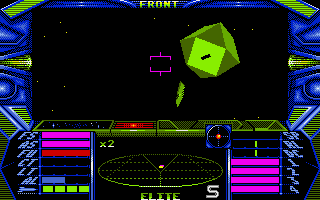

I bring up these articles in BYTE to stress that this proprietary chipset was truly the first of its kind in any consumer grade computing hardware, and it was far ahead of its time. By taking so many different functions off of the CPU, the machine was capable of more than any other machine on the market. For example, you can see some very big differences between the Amiga version of Elite vs that for DOS.

In 1987, correcting the low base memory issue (and allowing expansion up to 138MB), lowering the price to $699 (around $1893 in 2023), and bringing back the Commodore 128’s outward design, the Amiga 500 was what the A1000 ought to have been. This was a machine intended to directly compete with the Atari ST line of computers, and this machine returned to Commodore’s tried and true plan of being sold absolutely everywhere possible. The 500 also had a programmable floppy disk drive which allowed it to read 720K IBM PC floppies. The Amiga 500 sold well in Europe particularly.

Commodore also released the Amiga 2000 in 1987 and this was a decidedly more workstation-like machine than the A500. It could hold two three and half inch drives and a five and quarter inch drive. The A2000 shipped with 1MB of RAM and could be upgraded further. It could be configured with a SCSI HDD, and had a battery-backed real-time clock. This machine also had five, one hundred pin, sixteen bit Zorro II expansion slots; two, sixteen bit, ISA expansion slots; two, eight bit, ISA expansion slots; and one eighty six pin CPU/MMU expansion slot. The A2000 had an initial price of $1495 (around $4000 in 2023).

Of course, gaming wasn’t the only arena where the Amiga’s prowess was on display. Much of the graphics made for season one and two of Babylon 5 were created on an Amiga, as were those for SeaQuest DSV and Max Headroom. Naturally, third party products were created to take advantage of the Amiga’s abilities, and none is as famous as the VideoToaster. The video toaster was released in December of 1990 for $2399 (around $5600 in 2023). This was an expansion card for the A2000 and software on eight floppy disks. The user gained four inputs, dual twenty four bit frame buffers, and a chrominance keyer. This allowed a video editor to do all kinds of screen transitions and effects, generate titles, make graphic overlays, modify color balances, and even do full 3D modeling and animation. The main competition in this arena were SGI workstations which cost around $20000 where an Amiga with the VideoToaster would weigh in around $5000. It was the VideoToaster that allowed things like Babylon 5 to be achieved on an Amiga.

As the Amiga wasn’t as popular as IBM compatible PCs, Commodore attempted to make PC software run on the Amiga. The first product for this was the Sidecar. This was an expansion card that contained an 8088 system that connected to the side of the Amiga. With this card attached, a user could run PC software in a window on the Workbench. Later models named the Bridgeboard were made for the A2000 and successors containing an 80286 system, and then an 80386 system. Third party cards brought similar features to the A500, and there were also expansion cards that would allow the Amiga to run MacOS software. The catch with MacOS was the need for a Macintosh ROM. The Macintosh compatibility, however, was so good that an Amiga fitted with such an expansion card typically ran Macintosh software faster than a Macintosh.

The A500 and A2000 were successful enough that Commodore was finally on the rebound. The company posted $22 million (around $60 million in 2023) in profit in March of 1987, and the company had around $46 million (around $46 million in 2023) in cash. Then, on the 22nd of April, Irving Gould fired then CEO Thomas Rattigan and declared himself CEO citing a decline in US revenues of fifty four percent, and European sales providing seventy percent of Commodore’s sales. Apparently, despite being profitable once more, Gould wasn’t satisfied. He proceeded to promptly cut staff from roughly forty seven hundred to thirty one hundred, close five manufacturing plants, and reduce the North American operations to only sales and marketing with all other operations being in Europe. Eventually, roughly half of all employees in the States were laid off.

Comodore’s PC clones were unsuccessful in the USA just as the Amiga was, but they were doing well in Europe, just as the Amiga was, and the Commodore 64 was still the company’s main money maker. The company then began work on a new eight bit computer dubbed the 65 which was intended to be a Commodore 64 compatible machine capable of Amiga-like graphics and sound. Apparently, at least one of these was made as it was shown to a magazine at the Commodore Deutschland office in Frankfurt, Germany. In April of 1990, the company released the A3000 with an upgraded chipset as well as the A500 Plus and the A600. Commodore also released the CDTV which was a market failure.

In 1992, Gould shutdown the production and development of eight bit systems entirely with the Commodore 65 never having seen the light of day. The Commodore 3000 Plus and the later A4000 were doing well with a newer chipset, and the A1200 was released in autumn along with the CD32. These were slowly gaining market share throughout 1993 and 1994.

Unfortunately, in the middle 1990s, PCs were very quickly advancing and gaining ground against the Amiga’s capabilities. At the same time, Commodore’s management team chose to cease development of newer chipsets and technologies. The company was not well positioned to continue the fight in the market, and then came Cadtrak. Cadtrak had once been a workstation maker. They weren’t doing well at all in the early 1980s. In 1983, IBM contacted them for the licensing of a patent for moving a cursor on a screen (this patent shouldn’t have been valid given copious prior art). Apparently, the company really like this idea, and in 1985 the company laid off its employees and became a patent troll. In 1993, Cadtrak sued Commodore for patent infringement. Commodore lost and also refused to pay which resulted in the company being banned from importing and selling in the USA. The company was then forced into bankruptcy proceedings. New layoffs started on the 22nd of April in 1994, and on the 29th Commodore released the following statement:

Commodore International Limited announced today that its Board of Directors has authorized the transfer of assets to trustees for the benefit of its creditors and has placed its major subsidiary, Commodore Electronics Limited, into voluntary liquidation. This is the initial phase of an orderly liquidation of both companies, which are incorporated in the Bahamas, by the Bahamas Supreme Court. This action does not affect the wholly-owned subsidiaries which include Commodore Business Machines (USA), Commodore Business Machines Ltd. (Canada), Commodore/Amiga (UK), Commodore Germany, etc. Operations will continue normally.

Jay Miner once said, “You get what you pay for, except in the case of the Amiga where you get a little bit more.” I feel this was true of all of Commodore’s headline machines: The PET, the VIC-20, the Commodore 64, the Amiga. These machines were punching up in a rather major way.

I now have readers from many of the companies whose history I cover, and many of you were present for time periods I cover. A few of you are mentioned by name in my articles. All corrections to the record are welcome; feel free to leave a comment.