inMOS and the Transputer

Roads less traveled

Iann Merchant Barron was born on the 16th of June in 1936 in Watford, Herts, UK. At the age of sixteen, Barron read a news article about computers which were being sensationalized at the time. For Barron, this was life changing. He realized that computers would be his future. Sadly, for a curious mind there was little to be found on the topic. He did find a book by Douglas Hartree, Calculating Instruments and Machines, which provided him enough information to design a computer, but he wasn’t satisfied with this. Barron was a reader of the Times, and he’d seen advertisements from the NRDC. There wasn’t really anyone to tell him that he couldn’t so he wrote to Lord Halsbury asking him what, if anything, a young man like himself could do when finding himself interested in computing. Apparently, no young person had asked this before, and I suppose it amused Halsbury as he invited Barron to the NRDC offices in London. At that meeting, Barron met Halsbury, Chris Strachey, and Donald Swann. The three men were thoughtful and kind, and they ultimately suggested that Barron go to Elliott’s.

Elliott Brothers was an extremely early computer company. The company had existed quite some time before getting into the computing industry, but the Elliott 152 was made operational in 1950 for the UK military. The 152 transitioned the company to being primarily a computing company for some time. This was followed by several more computers in rapid succession. Between his secondary education and university education, around 1954, Barron worked at Elliott’s. His primary occupation there was as a programmer, and this didn’t sit well with Doctor Sheiler who felt that Barron was young, inexperienced, and knew nothing. This, naturally, motivated Barron to compete. Writing software for the second Elliott Brothers’ computer, Nicholas, wasn’t a great experience. The computer’s I/O was exclusively a paper tape affair, and it was a real-time system. Sheiler had written a program to automate the paper tape punching and conversion, and Barron rewrote it. Barron’s version implemented interleaved binary/decimal conversion and operated at twice the speed. He’d proven himself adequate to the task of programming, and I can only imagine that Sheiler was rather annoyed. On each break from university, Barron returned to Elliott’s.

In 1958, with his degree completed, Barron was called up for National Service. A day prior to his departure, he received a phone call from the War Office. Someone had mentioned to some other person who held some amount of power that Barron was well versed in computing technology, and rather than joining the Army, Barron served his country working on computer technology at the Air Ministry in Whitehall, and later at the Fighter Command in Stanmore, and finally at the Bomber Command in West Wickham.

In 1961, leaving the Royal Air Force, Barron contacted Elliott’s. He said he’d like to come back to work for them and research software. They hired him, and then upon arrival things changed. While he was returning, another employee was leaving. The company had a contract to fulfill and a computer to complete, and Barron was asked to take over. This computer was for the Royal Radar Establishment. It was deployed successfully and handled the operation of the radar systems, the collection of their data, and the presentation of their data (though it wasn’t initially designed to do the actual radar controls). This work was followed by yet another computer design due staffing issues at the company, and ultimately, Barron never got to do what he was initially hired to do. Barron’s employment at Elliott Brothers finally ended when he was asked to build yet another high performance computer, and Barron responded with a suggestion that the company should license the DEC PDP-8. When the company refused his suggestion in 1965, he quit, started a new company, and several people left with him.

The company Iann Barron founded was Computer Technology Limited in Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom. It took around six weeks for him to secure funding. This is extremely impressive when one considers that the UK didn’t have a start up scene, and that it didn’t yet have a tradition of privately funded scientific companies. The two primary funders were Robert Maxwell and Arnaud de Vitry. In Maxwell’s case, the money was his own. In the case of de Vitry, the money came from his venture capital firm, American Research and Development. De Vitry had previously invested in DEC, but DEC was adopting integrated circuits too slowly for De Vitry’s liking. Meanwhile, Barron was suggesting using integrated circuits as much as was possible at the time. Naturally, de Vitry wanted to be involved.

CTL’s first computer was the Modular One which went on sale in 1968. The computer was 16 bit and built with ECL. The “modular” name comes from it being built of separate processor, memory, and peripheral modules. These modules shared their form factor (19.7 inches wide, 19.7 inches deep, 27.6 inches tall) and interface which allowed them to be combined in a somewhat arbitrary fashion in either one or two racks. The most typical configurations weighed in around sixty pounds.

Despite having a good machine, CTL didn’t do well. The UK computer market wasn’t quite as large as the American, and DEC was taking over the market for minicomputers. To keep the board happy, the financial managing director was cooking the books and claiming sales that hadn’t yet materialized. When Barron brought this information to the board in 1975, the board chose to fire the messenger and not the perpetrator.

Of course, the 1970s were an interesting decade. Microprocessors had just been unleashed on the world, and Barron took some time to learn everything he could about them. In his own words, he wanted to become the

world’s expert in microprocessors. Given that the most advanced processors available in 1975 were the MOS 6502, the Intel 8080, the Motorola 6800, and the TI TMS1000, this was actually an achievable goal.

Having achieved considerable expertise in microprocessors, Barron was tasked with organizing a panel of speakers on the future of computing for the International Federation for Information Processing conference in 1977 in Toronto. He had someone on board for architecture, for software, and several other topics, but he lacked someone to speak about semiconductors. He eventually found the person he needed in Richard L. Petritz. Unfortunately, while Petritz had written on the topic at length, and while the committee responsible for the event wanted him to be there, Barron didn’t hear from him. Barron was fully prepared to give a talk himself. Happily and amazingly, Petritz arrived right on time, he gave a competent talk, and everything was fine. After the first day of the conference was over, Barron invited everyone to go have a drink. They all arrived at the bar, and Petritz sat next to Barron. After some time and much light hearted discussion, Petritz asked Barron if he’d like to start a new semiconductor company. But, this was the end of a long day, Barron was out of it, and he ignored him. Saturday came, and the conference was over. Barron was getting on a plane to fly to Motorola in Austin and was having a bit of difficulty with customs officials. Petritz serendipitously showed up and helped smooth things over, and then while in flight, he again asked Barron if he’d like to start a new semiconductor company. Barron replied no. Barron had absolutely no intention of working and living in the USA. It just wasn’t for him. The two discussed this for sometime, and Petritz eventually stated that should Barron be able to secure funding the UK, he could always have his bit of the company in England.

Arriving back in the UK, like every half-way wise husband, Barron spoke about the idea with his wife. His wife gave him her endorsement (more or less), and the next week Barron met with the chairman of the National Enterprise Board, Sir Leslie Murphy. The NEB was interested in boosting semiconductor technology in the UK, and the thought of being able to import the technology from the USA was tempting enough. The NEB provided £50 million to the startup, inMOS, which was founded in July of 1978. One key technology that Barron immediately jumped on was the wafer stepper; this was actually included in his proposal to the NEB. Wafer steppers were still new, and Barron’s new company bought all that were available at the time. These allowed the photolithographic mask for an IC to be reduced in size many times over eventually allowing for sub one micron fabrication. The tradeoff for this was that instead of imaging an entire wafer at one time, each chip would need to be imaged individually.

The first product that inMOS produced was a 16K static RAM, which was followed by dynamic RAM in 16K and 64K sizes. Rather quickly, inMOS began taking the market for RAM chips and grew to control around sixty percent of that market. Yet, the company didn’t see profitability despite that large market share. Barron’s business plan had projected losses through 1983 with 1984 being the first profitable year. This was achieved with £150 million in revenue and profit of around £14 million. Despite becoming profitable, the NEB had invested £65 million and Maragaret Thatcher’s government was keen to privatize and cut the government’s expenses. The government found a solution in Thorn EMI who bought the government’s seventy six percent holding in inMOS in September of 1984 providing the government a £30 million profit on their investment.

Much like Sun, HP, and Intel a few years later, inMOS began exploring multiprocessing as CISC CPUs seemed to be hitting performance plateau. However, inMOS’s solution was rather unique. What Iann Barron envisioned was a processor that could link with arbitrarily many others to make a parallel processing system, and his hope was that the system would achieve nearly linear scaling with each new element. The chip that enabled this was called the transputer, and while Barron dreamt it up (and had actually start inMOS with intent of producing it), David May and Robert Milne were the designers. The transputer wasn’t intended to compete directly with Intel and Motorola in their market, but rather to hit embedded platforms and the very high end. While there were a few models of transputer chips, they all had a rather interesting set of features: an integer processor, static RAM on chip, four bidirectional serial links for communication with other transputers, a memory interface for external memory, real time process scheduling, a timer, and in later models, an on-chip floating point unit. Importantly, both inMOS and many transputer fans refer to the device as being a RISC chip, this isn’t entirely accurate. It had a leg in both RISC and CISC. On the RISCy side, the transputer did achieve (on average) one instruction per clock, had instructions of a uniform length, and had a very limited number of instructions. On the CISCy side, it was heavy on microcode (essentially a tiny and minimal operating system was implemented in microcode), had just three data registers and those behaved more like a stack, used complex memory instructions, and the instructions themselves were kind of weird (8-bit, and split into two nibbles where one was the primary instruction code and the other was a constant). So really, the transputer was both RISC and CISC, and still not quite either one. It was really its own beast entirely.

At a time when n-channel MOSFETs were extremely common, transputers were manufactured with CMOS (P-MOS and N-MOS sources and drains connected in parallel) which was still relatively new for microprocessors, though it was already common in digital wristwatches and pocket calculators. By the end of the 1980s, CMOS would completely replace N-MOS, and the reasons for this shift are visible in the benefits that the transputer had by being CMOS-first: lower power consumption, lower heat production, greater predictability. One other choice that was made early was to use CAD rather than pencil and paper drafting and circuit analysis. This required the company to design their own CAD workstation and processor design software. The CAD workstation and design software were mostly created by Colin Whitby-Strevens, while the layout of the transputer on that workstation was done by a team led by Miles Chesney. Of course, when one considers that essentially an entire computer (sans peripheral controllers and storage [most of the time]) was being put onto a single chip, the use of CAD becomes an obvious necessity.

A completely new architecture that operated very differently from all prior machines would certainly require new software. That software, to take full advantage of the transputer, would need to be written with the parallel architecture in mind. For this effort, inMOS created the programming language Occam named after William of Ockham. The language was primarily developed by David May but many people at inMOS worked on it. It’s is an imperative procedural language, it’s indentation sensitive, and each expression is terminated by end-of-line. I won’t put a course in the language here, but I will highlight some of the more unusual parts of the language. First, while all software is essentially just sequence, selection, loop, and data structures… sequence isn’t implicit in Occam. Being a parallel first language, for anything to be assuredly done in sequence one needs to to use the SEQ keyword. For concurrent evaluation, one would use the PAR keyword. While the transputer doesn’t have a single shared bus, it does have named channels. Output to a channel is accomplished with a ! while input from a channel is accomplished with a ?. Notably, the channels are super important as Occam’s processes cannot access the same memory, and they therefore share data over the channels instead. This channel use instead of shared memory prevents deadlocks. The first version of Occam was ready in 1983 when the first transputers were announced. This date precedes the chip itself as Occam was made before the transputer. This was done to ensure that the transputer would lack unused instructions and that hardware and software would be optimized for one another.

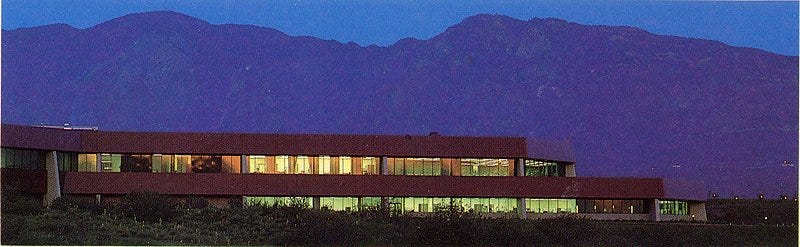

I suppose this as good a time as any to say that making a fab is hard. Really, really hard. In the USA, there was already a rich pool of talent for building semiconductor fabrication plants. While in the 2020s it isn’t the case, the USA had many fabs in 1970s and 1980s. In the UK, there was rather a lack of fabrication plants, and there was likewise a lack of chip fab experts. More severe a problem, the US and UK arms of inMOS just didn’t get on. Help from the USA’s fab in Colorado Springs wasn’t exactly forthcoming when the UK team were building their fab, but the fab was built never the less and was on Cardiff Road in Newport, Wales, UK.

Shortly after getting the UK plant up and running, the company realized that their chips were suffering from metal fatigue and yields were low. Around Christmas of 1982, the company realized that the water they had was contaminated, and this was apparently coming from their chemical reservoirs (essentially tin cans full of resins used for de-ionization that were roughly nine feet in diameter and roughly twenty six feet tall). All hands were brought in to shovel the resins out, repair the tanks, and then fill them back up with resin. Not too long later, the American branch took over management of the fab despite the issue having been caused by the water utility having dumped too much chlorine into the water supply.

Around this time, the value of the pound fell sharply which served to further strain the company. As noted earlier, the company did survive all of this and still managed to get their RAM chips out, and the transputer research and development work continued, the company just wasn’t doing terribly well.

So, Iann Barron’s vision was being funded by the sale of memory chips, developed by a company struggling to keep operating, using a state of the art fab run by a half of the company somewhat hostile to all UK development efforts, and yet, it worked. The transputer was first released in 1984 with the T200 series. The T212 and the M212 were 16 bit chips and featured clocks of upto 20 MHz (varieties capable of different clock speeds were available) and 2K RAM. The primary difference between the two chips was that the M212 came with an integrated disk controller, a very uncommon feature for a transputer, I think this was the only version to do so. Not too long after, inMOS released the T222 which increased the RAM to 4K, and then the T225 added breakpoint support. The T222 and T225 could address up to 64K RAM off-chip, and they could achieve performance of around five million instructions per second in their more modest configurations.

inMOS announced the T424 in 1984. This was a 32 bit chip with 4K RAM capable of nearly 20 MIPS and which could address up to 4G of off-chip RAM. While the chip wasn’t released until late in 1985, it was good for the brand to announce early as several other 32 bit chips were announced in 1984: Data General Microeagle, DEC Micro VAX 1, HP FOCUS, Intel 80386, Motorola 68020, National Semiconductor NS32032, NCR/32, Western Electric WE32000, Zilog Z80000. The 1980s were crazy. The T414 did ship in 1984 with 2K on-chip RAM, but the 424 was delayed and didn’t launch until 1985. Both of these came in 15 MHz and 20 MHz varieties often referred to as T414-15 or T414-20. A T425 launched a little later with 4K RAM and the breakpoint instruction support, and the it came in 20 MHz, 25 MHz, and 30 MHz varieties. In September of 1989, a low-cost T400 chip was released at 20 MHz, 2K RAM, and just two chip interconnects instead of four. This version was the first serious attempt at breaking into the embedded market. I find it interesting that inMOS’s quoted performance was just ten MIPS. This was actually on the low side, and that figure assumed large data sets and complex tasks. Using the 20 MHz T424, small constants, and a relatively low number of context switches, around sixteen to twenty MIPS was achievable. The link speed between chips for the 16 bit and 32 bit series of transputers was 10 Mbps per link, and all four links could send/receive at that speed simultaneously.

The inMOS T800 series was introduced in 1987 with an on-chip, 64 bit, floating point unit. The chip had three registers for floating point and these were once again similar to a stack. While inMOS was late to the floating point world, it did properly implement floating point on the first attempt with the IEEE 754 standard. Like earlier versions, T800 series featured 4K of on-chip RAM, and was available in multiple clock speeds. The T805 was unique in that it offered separate address and data links.

Nearly all early transputer systems were used with a host machine. The transputer boxes were essentially rather boring metal boxes that fit neatly in a rack or sat on a desk. The other way one found transputers was add-in cards for IBM PCs or Motorola 68000 workstations. Essentially, the transputer was used in a way that is eerily similar to modern GPUs. Specific workloads requiring high amounts of parallelism would be offloaded to the transputer while mos other tasks were handled by the host machine. This was partially do to a lack of I/O controllers in the transputer, but also due to a lack of virtual memory support. This meant that an operating system like UNIX couldn’t be used on the transputer (at least not initially). Those transputer machines that were not of add-in card type were typically supercomputers, and these usually still made use of workstation hardware to act as the host(s) and/or as terminals.

MicroWay offered an add-in board for 80386-based PCs that can help us to get a sense of the pricing involved in these systems. In late 1987, one could purchase the Monoputer board with a single T414-20 for $1495 (around $4058 in 2024) and this would include an Occam compiler and 2MB of RAM. A Monoputer with a single T800-20 would be $1995 (around $5416 in 2024) again with 2MB of RAM. The Biputer was essentially the same product but with two transputers on the board, one T414-20 and one T800-20, and cost $4995 (around $13561 in 2024). The Quadputer was a board featuring four T414-20s and it cost $6995 (around $18990 in 2024). MicroWay stated that a single T800 was roughly equivalent in power and performance to an 80386, and they offered Occam, C, Fortran, Pascal, and Prolog compilers for both MS-DOS and Microport UNIX all targeting the transputer.

The only product that used solely transputers (of which I am aware) was the TV-Toy. This was a joint project between inMOS and Sinclair to develop a game console, but I wasn’t able to find much information about it. For Sinclair sources, there are multiple machines that never surfaced like LC3, the SuperSpectrum, and the Loki, but all of those were designed around other CPUs. We do know that the TV-Toy was intended to have been built around the M212 and this was the primary reason for the inclusion of a disk controller in that chip unlike all other transputers.

Meiko was founded in March of 1985 by former inMOS employees Miles Chesney, David Alden, Gerry Talbot, Roy Bottomley, Eric Barton, and James Cownie. One year after starting, they launched the Meiko Computing Surface (or CS1) which was built around the T414. This was a massively parallel supercomputer and it was relatively successful. In 1987, the company launched MeikOS. This was a UNIX-like operating system developed from Minix which ran on the CS1. By 1988, the company had one hundred seventy five customers. The “front end” or host for the CS1 could be a DEC VAX, a Sun workstation, or one of a few IBM models. Later versions of the CS1 and all subsequent Meiko supercomputers utilized other processors. Meiko also offered cards for Sun workstations built around their CS1 transputer architecture. The workstation class products had performance in the range of around 3 MFLOPS, with a single mainframe operating at around 1 GFLOPS. Their standard M40 configuration (forty boards, one nineteen inch rack) achieved about 150 MFLOPS and had 500MB of RAM. According to Rolls Royce, their CS1 was competitive against a Cray.

Among the more famous transputer-based systems (though certainly the least successful in the market) was the Atari Transputer Workstation 800. The computer was announced at COMDEX on the 2nd of November in 1987. They stated that the machine was seven times faster than the Mac II, and a prototype clear-cased machine was shown with multiple graphical demonstrations running concurrently. The machine was then scheduled for release in mid-1988 with pricing starting at $5000 (about $13035 in 2024). The ATW packed a T800-20 with 4MB of RAM and was expandable to 16MB alongside a what was essentially a compact Mega ST system with 512K RAM that operated as the host for the transputer. Screen output was handled by the Blossom board that had 1MB of RAM and was capable of 1280x960 with 16 colors out of 4096. At lower resolutions, Blossom could handle significantly more color with the resolution of 512x480 supporting 16.7 million colors. Blossom also had blitter-like functionality and could apply several textures to any given object. The machine had an additional four slots to add more transputer boards, and a slot for an inMOS crossbar switch (think of a co-processor that handled coordination of inter-chip communications). When fully upgraded, the ATW could house seventeen transputers at 20 Mhz with the crossbar speeding up communication between them. If MicroWay’s performance comparison is accurate, the ATW would have had an upper performance limit nearing a rack’s worth of 386 machines and among the best graphics systems available. For software, the ATW ran Helios. Helios was a UNIX-like operating system developed by Perihelion Software that used a microkernel handling memory allocation, process management, and message passing. Around that were libraries for for various things, the most important of which was the system library which translated C function calls into Occam statements for the transputers while also handling IPC and networking. Helios was UNIX-like enough that it could run most UNIX software.

While the transputer was being used for super computers, add-in boards, spurious workstations, and non-existent game consoles, inMOS’s memory business took a hit. Most of the RAM business had been transferred to the US fab, and the RAM business still represented the majority of income for inMOS. As a great way to ruin a day, a faulty piece of equipment used at the fab led to faulty RAM chips, and quite a bit of the management at the Colorado Springs fab were fired. Ironically, Iann Barron was sent to the USA to manage the fab. Things continued to go poorly, and Barron sold the US half of the company to Seymour Cray. Meanwhile, the UK half of the company was still operating under Thorn. As the transputer became less competitive against the Intel 80386, the Motorola 68030, Acorn ARM2, and the DEC Rigel, inMOS mostly made money off of patents, about £200 million worth. One interesting patent negotiation was with IBM, where the two companies essentially granted each other access to their respective processor and RAM patent portfolios. As an outcome of this deal, one of the transputer’s test chips at inMOS that dealt with video output was repurposed for IBM’s SVGA.

In 1989, inMOS was sold to SGS Thompson. While Pasquale Pistorio liked the transputer and worked to revive it, it would have needed to have been redesigned for newer fabrication processes. This would have taken a rather serious amount of time with estimates placing tape out at 1991 assuming very little went wrong along the way. This was started, and was named the T9000, and it was never a success though a few made it into the wild. At one point, the team at SGS Thompson considered, and even partially designed, a 64 bit transputer utilizing four address units, four ALUs, two FPUs, and four 50 Mbps links. This too would simply have taken too much time to become viable.

While patents and ideas from inMOS have proliferated throughout the industry, one of the most interesting outcomes was that the transputer interconnect became the IEEE 1355 standard which then became SpaceWire. inMOS employee and Meiko cofounder Gerry Talbot helped in the creation of HyperTransport and PCI Express using some of the ideas from IEEE 1355, so Infinity Fabric and the Zen chiplet interconnects descending from HyperTransport are cousins of that same technology. David May, one of the two creators of the transputer, went on to cofound XMOS, a fabless semiconductor company, with Ali Dixon, James Foster, Noel Hurley, and Hitesh Mehta. The company primarily creates heavily multicore microcontrollers and audio controllers that draw significant inspiration from the transputer and its channels and threads. In December of 2022, the company announced that it would be moving to the RISC-V ISA while keeping the underlying architecture of their xCORE line where the crossbar becomes xconnect, and an eight core chip can handle one billion instructions per second, with 1MB on chip SRAM, integrated USB 2.0 host, serial communications, secure boot support, and consuming something in the neighborhood of 465mW of power.

Everything I’ve done has been accidental, I think. It doesn’t sound good, does it? But, the central view of life, to be successful, you’ve got to actually be pretty clever one way or another, you’ve got to work bloody hard, and you’ve got to be extremely lucky.

— Iann Barron

I now have readers from many of the companies whose history I cover, and many of you were present for time periods I cover. A few of you are mentioned by name in my articles. All corrections to the record are welcome; feel free to leave a comment.