The Mark Williams Company

And the COHERENT operating system

William Mark Schwartz was a chemist living in Chicago and running a chemical company called the Mark Williams Chemical Company. Some of his employees complained of issues like fatigue, headaches, and indigestion which prompted him to create a beverage that would solve these issues. These complaints were more of the “man, I am tired” variety and not that Schwartz was working them to death. This beverage was Dr. Enuf, likely developed in 1949, for which Schwartz applied for a trademark on the 19th of May in 1951. The trademark was granted on the 2nd of December in 1952, and the beverage was first sold commercially on the 4th of April in 1951. The company produced paints and other products as well (being a chemical company), but Dr. Enuf is the most famous. The rights to the formula for Dr. Enuf were eventually bought by Charles Gordon of Tri-City Beverage in Johnson City, Tennessee.

William Mark Schwartz’s son, Robert Schwartz, didn’t wish to follow his father into chemistry. He was a software developer, and he wanted to move the company into that field. Specifically, Robert Schwartz saw the introduction of the microprocessor and early microcomputers as having extreme potential. This transition occurred in 1977 and the “Chemical” was dropped from the name, and the new Mark Williams Company was headquartered in Northbrook, Illinois.

Stephen A. Ness joined the computer science department of Stanford University as a graduate student in the autumn of 1968. Unfortunately, his interested began to fade, so he spent quite a bit of time going to movies. He started working at the Festival Cinema in Palo Alto sweeping floors, cleaning bathrooms, and running the projectors. He was a movie buff and this worked for him for some time. As his interest in working at the theater was beginning to wane, he began to long for a job in software development. In early February of 1977, Donald Knuth paid a visit to the theater and asked Ness what he was up to, Ness told him about his job search. The next day, Knuth got a call from Schwartz. Schwartz was searching for a programmer and Knuth provided Schwartz with Ness’s number.

The start of the microcomputer world was dominated by BASIC. More particularly, it was dominated by Microsoft BASIC, and Schwartz wanted to compete. Ness told Schwartz that he could build a BASIC interpreter in about four months, which was just a guess on Ness’s part. He hated BASIC, but he was familiar enough with it, and he really wanted the job. On top of that, Schwartz was letting him work from home. With both parties satisfied, work began. Of course, this “working from home” was complicated. Disk drives of any kind were expensive and difficult to come by, so Ness commuted from Palo Alto to Pacific Grove where he used Gary Kildall’s computers until he purchased his own machine and disk drive later in the year. The BASIC that Ness built for the Mark Williams Company was XYBASIC.

Getting a start early on in the computer revolution with a BASIC was a good idea. BASIC was everywhere, and it was a product that would sell. Revenues from XYBASIC allowed the company to expand into operating systems. MWC purchased a PDP-11 in the late 1970s and began working on a UNIX clone. This would allow them, just as XYBASIC did, to offer a stellar product at a price far lower than any of the competition. COHERENT was first sold through OEMs for PDP-11 minicomputers in 1980. However, it was quickly ported to the Zilog Z8000, the Motorola 68000, and the 8086. It was offered at retail to owners of machines utilizing these CPUs in the spring of 1983. One OEM who picked up COHERENT was Commodore.

The workstation Commodore was building was the C900. This system offered a 1024x800 display on a screen of either fourteen or twenty inches, a 20MB HDD, a 1.2MB five and quarter inch floppy disk drive, two RS232 ports, a Centronics port, an IEEE-488 port, 512K RAM, and the COHERENT operating system version 2.3 with both BASIC and C. The C900 could be expanded with hard disk upgrades up to 67MB, memory up to 2MB, and RS232 port count up to eight (for a total of eight terminals for concurrent multi-user support). On the software side, add-ons included: Pascal, COBOL, plotting software, and graphical terminal support. The C900 was built in Germany with a US release scheduled for the third quarter of 1985. Pricing started around $2700 (about $7740 in 2024).

Unfortunately, the C900 project was canceled with very few units having made it to market. Commodore’s focus shifted to Amiga, and their UNIX workstation aspirations disappeared.

Thankfully, the IBM PC and its clones were selling well and COHERENT was also present there for $500 (about $1433 in 2024) requiring a minimum of an IBM PC with a hard disk. With just an IBM PC and a hard disk, COHERENT could support three concurrent users with terminals attached via serial ports.

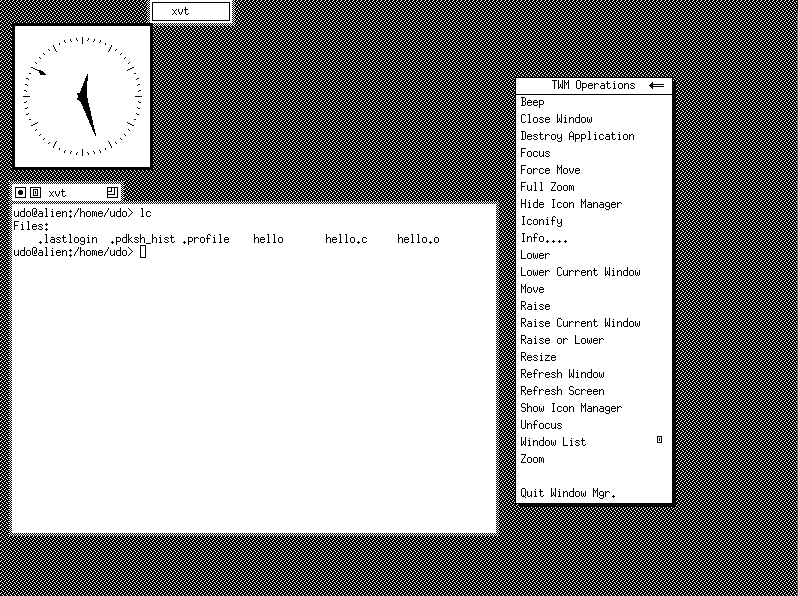

Given that UNIX licenses were prohibitively expensive during this time period, COHERENT was quite a good deal. Adding that it included both a C compiler and a BASIC compiler, COHERENT was easily the most affordable workstation operating system and software development suite available at the time. As for what COHERENT really offered, it was essentially V7 UNIX complete with nroff, diff, sed, ed, awk, lex, yacc, db, man, bc, make, the Bourne shell, and other expected utilities. This system was packed onto seven double-sided floppy disks, and packaged with a manual.

Of course, AT&T didn’t exactly love the idea of someone offering a UNIX-like operating system for substantially less money while also not paying them their due. So it was that around the time that the PC port was made, AT&T sent Dennis Ritchie went to the Mark Williams Company offices in Northbrook to ascertain whether or not COHERENT represented an instance of intellectual property theft. According to Ritchie, the offices were in an industrial area and the feel of the premises hadn’t strayed far from that of a paint company. As for the investigation of COHERENT, Mark Williams Company would not allow AT&T to have a look at their source code, and therefore the most that Ritchie could do was look around the system. He had notes with him about specific things that could indicate a direct copy without much doubt, but that was the most he could do. His conclusion is that COHERENT was made with considerable study of AT&T UNIX, but that it wasn’t a direct copy. He stated:

It was very hard to believe that Coherent and its basic applications were not created without considerable study of the OS code and details of its applications. Looking at various corners convinced me that I couldn't find anything that was copied. It might have been that some parts were written with our source nearby, but at least the effort had been made to rewrite. If it came to it, I could never honestly testify that my opinion was that what they generated was irreproducible from the manual.

Given that the making of a UNIX-like operating system required a C compiler, the MWC C compiler was quickly ported to other systems and offered as a standalone product starting in 1981. Porting the compiler to MS-DOS was a given as IBM compatibles running MS-DOS dominated the market by the middle of the 1980s and COHERENT was offered for those machines. MWC offered their C compiler for MS-DOS at a price of just $75 (around $254 in 2024) and an advanced interactive debugger was offered for another $75.

In early 1986, the Mark Williams company began offering their C compiler for the Atari ST. This software package came with a rather complete manual that covered the C compiler itself in five hundred twelve pages, the make utility with another twenty five pages, and Micro EMACS in another seventy seven pages. Beyond cc, make, and emacs, the MWC C compiler for the ST shipped with a symbolic debugger, assembler, linker, and a series of libraries that offered sorts, enums, and a random number generator. This product sold for $180 (about $506 in 2024). In autumn of 1987, MWC followed up with version 2 of their C compiler for the ST. This version increased the compiler’s speed, added RAM disk support for temporary files, a shell that implemented a small subset of UNIX commands, and improved documentation. STart Magazine’s review stated the product was without equal.

From what I can gather, COHERENT version 1 was only available on the PDP-11. COHERENT version 2 began shipping on OEM systems, and the point releases of 2.3 and 2.5 were offered at retail while also having been present on some OEM systems.

COHERENT version 3 was released in May of 1990 for $99.95 (about $235 in 2024). It required a 7MB or larger HDD, 640K RAM, a high density disk drive, and at least an Intel 80286 CPU. Given the nature of the 286, the kernel fit in just 64K RAM with support for multitasking and and multiple concurrent users. This was still a V7 UNIX clone and it continued to lack BSD enhancements (like vi), though it did come with Emacs. It also lacked the Korn shell, X, SCSI support, and MCA support. The COHERENT manual at this point was one thousand pages. COHERENT v3 sold around forty thousand copies between 1990 and 1992 which would have resulted in revenues around $4 million (nearly $10 million in 2024).

COHERENT version 4 was released in May of 1992 for $100 (around $219 in 2024). This version made COHERENT a fully 32 bit operating system and required at least an Intel 80386 CPU and 1MB of RAM. This version also brought official support for X Windows and MGR to COHERENT for the first time. This version was roughly compatible with UNIX SVR3.

COHERENT version 4.2 was released in 1994. This version brought STREAMS, POSIX.1 and POSIX.2 compatibility to COHERENT making it largely compatible with UNIX SVR4.

The 1990s were tough. COHERENT was always a distant second to XENIX, but the early 1990s brought more competitors into the mix. BSD was making its way onto X86 compatible machines with many improvements over AT&T UNIX with a cost of zero dollars while Linux was quickly growing and gaining market share with SLS, Slackware, and Debian, add to both of those that the commercial UNIX workstation market in general was losing ground to Windows NT. Likewise, the ST, where MWC saw the most success with their programming language tools, was no longer popular enough to provide significant revenues. These pressures all came to a head and the Mark Williams Company closed in 1995. In 2001, Stephen Ness archived the MWC sources at the request of Robert Schwartz, and in 2015 that source code archive was released under a 3-clause BSD license.

I now have readers from many of the companies whose history I cover, and many of you were present for time periods I cover. A few of you are mentioned by name in my articles. All corrections to the record are welcome; feel free to leave a comment. A few of my readers have asked about this, so if you have something you’d like to send in, there’s a P.O. Box at the bottom of the email.

I like Ritchie's comment: "Looking at various corners convinced me that I couldn't find anything that was copied. It might have been that some parts were written with our source nearby, but at least the effort had been made to rewrite."

Thanks for covering this company in depth. Mark Williams is a very interesting company. It didn't have a huge part to play in computer history, but it did play a part. It was the first company to copy Unix, the first of many.