Tandy Corporation, Part 3

Becoming IBM Compatible

This article follows Part 1 of the Tandy Corporation’s history, which covers the company’s founding and the lead up to and launch of the TRS-80, and Part 2, which covers the TRS-80 Models I, II, III, CoCo, and Pocket Computer.

When the TRS-80 Model I was released in 1977, the microcomputer market was small, centered around hobbyists, and many computer owners had built their machines from off-the-shelf components and/or kits. Tandy, Apple, and Commodore completely changed the market, but even their earliest customers had been hobbyists. After the release of VisiCalc, the market changed. Office workers, small business owners, people with complex finances, these all had VisiCalc as reason enough to own a computer. With WordStar, dBase, and CP/M, a new software standard had emerged, and sales increased further still. Oddly for Tandy, that VisiCalc was released first on the Apple ][ caused them an initial market share loss while overall increasing the size of the market over time and thereby having an overall positive effect on Tandy’s sales.

In 1980, Philip North promoted John Roach to the position of COO, and in 1981, Roach became CEO. At the start of 1981 as Roach was taking control of the company, Tandy’s market position was excellent, with TIME Magazine having stated on the 2nd of March:

In 1981 about 75% of the personal computer industry’s estimated $1 billion in sales will be controlled by just three companies. They are:

Tandy. The Fort Worth-based Tandy Corp. has the broadest reach of any computer manufacturer through its 8,012 Radio Shack stores. The firm introduced its first small computer, the TRS-80, in 1977. A newer version of the the TRS-80 (popular models now cost $999) has become the largest-selling computer of all time, and Tandy now commands 40% of the small-computer market. Tandy recently introduced the first pocket computer, which shows only one line of information and sells for $249.

Apple. The story of Apple Computer has by now become part of American folklore. The business was officially founded in 1977 by Steven Jobs and Stephen Wozniak, two college dropouts who scraped together $1,300 from the sale of a Volkswagen to build their first prototype. In 1980 Apple’s revenues topped $184 million, and the public offering of its stock in December was one of the biggest and most successful stock launchings in the history of Wall Street. The company is now aiming its sales effort primarily at the educational market, under the assumption that children who are raised on Apples are likely to buy Apples for themselves when they get older. A basic version of its hot selling Apple II costs about $1,435. The firm recently introduced the Apple III model, which is expected to help push sales this year to $250 million.

Commodore. The PET computer (cost: $995), which is manufactured by Commodore International, based in Norristown Pa., is the bestselling personal computer in Europe. The company has not been a major factor in the U.S. market but Commodore President James Finke says: “We’ve got 60% of the market in Europe and we’re now ready to compete head on with anyone.” This month it started running full-page ads in leading U.S. newspapers that read: COMMODORE ATE THE APPLE. This spring the company will introduce the VIC 20 computer, aimed at the home market and selling for $299.95. Commodore sales this year are expected to grow by 40% to $185 million.

The article went on to mention that Hewlett-Packard, Texas Instruments, Zenith, Atari, and IBM were all expected to enter the market, and then mentioned the warning from Jack Tramiel: “Gentlemen, the Japanese are coming.” And further, from Jon Shirley, the VP of Radio Shack at the time: “The Japanese are bound to be competitive, and I worry about the Japanese much more than IBM.” With the benefit of history, you and I know that both IBM and the Japanese manufacturers were going to be competitors that would end many companies, change the market forever, and raise an entirely new software standard. The author of this article, Alexander Taylor, ended with a note that the battle for the market would determine whether or not Panasonic and IBM would become as common as Radio Shack and Apple. There’s then a small insert about VisiCalc selling better than games, and as a sign of the primitive state of the market, the article had to explain the importance of software, how such a program could be used, and why one would want it. That insert then ends with a statement: “VisiCalc is obviously one of the compositions that is in no danger of fading from the charts.”

Announced in January of 1982 and released in February, the TRS-80 Model 16 was an improvement to the Model II; though, it was one that departed strongly from its predecessor in technology while staying the course in market segment. The Model 16 was based around a Motorola 68000 at 6MHz with a Zilog Z80 serving as an I/O processor unless or until 8bit Model II software needed to be run. This model also introduced half-height eight inch floppy disk drives, and could be ordered with either one or two. At the time of introduction, the computer had only TRSDOS-16 available, and there were exceedingly few native applications meaning that owners would have to use Model II software and therefore wouldn’t need to spend $4999 (around $16,618 in 2025 dollars) for the Model 16. This particular problem was solved when Tandy began offering XENIX on the Model 16 along with Scripsit 16, Multiplan, and Profile 16. For programmers, XENIX obviously brought C with it, but Tandy had COBOL and BASIC available as well. For software like VisiCalc, the Model 16 still offered an advantage: more RAM. CP/M could be loaded on the Z80, and the greater memory capacity of the Model 16 (from 128K up to 1MB) could be used via banking.

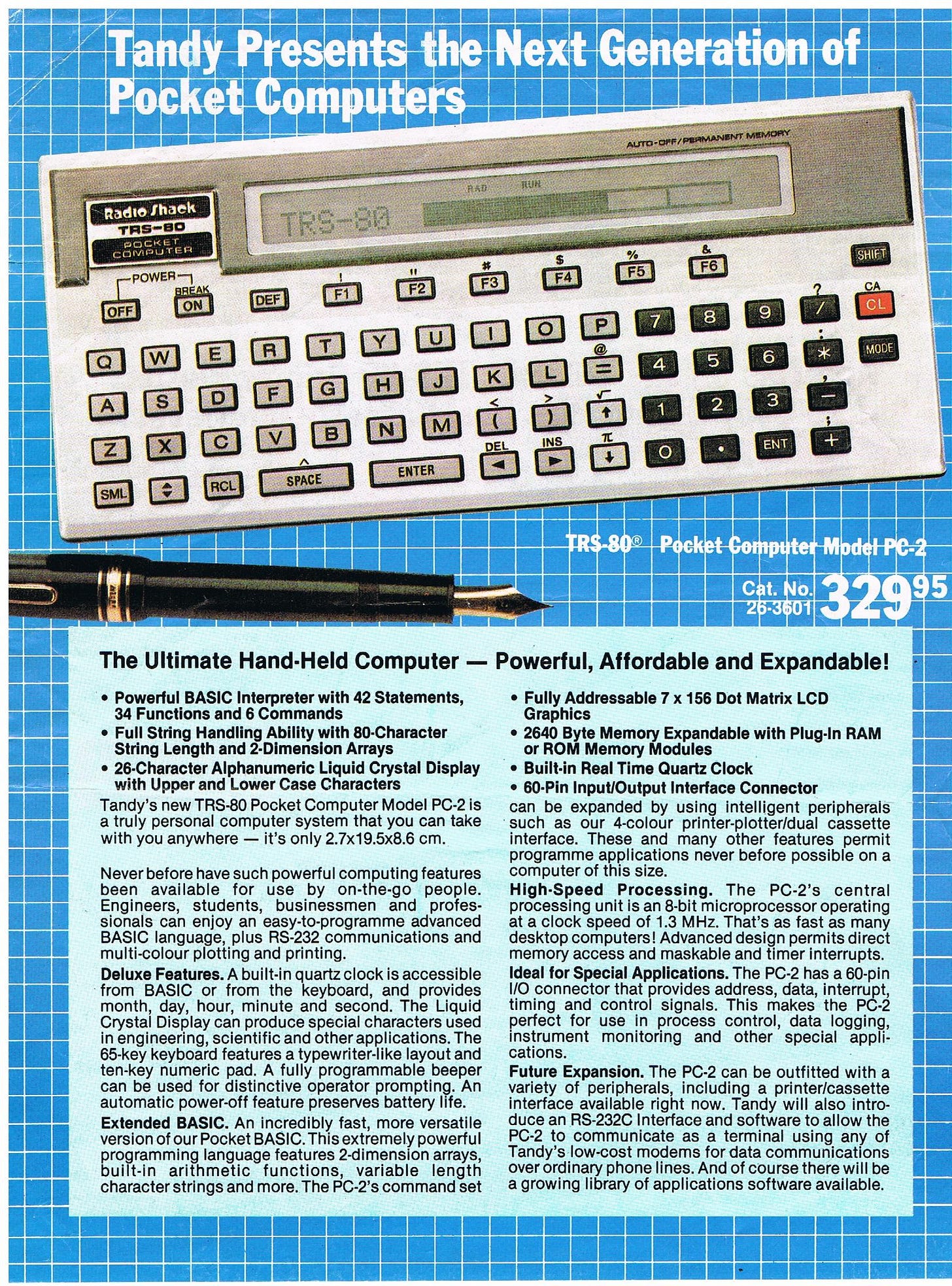

Around the same time, Tandy launched the Pocket Computer 2 (or PC-2) initially at a price of $279.95 running on four AA batteries yielding around 75 hours of run time with its 1.3MHz LH5801 processor. The machine had a 16K ROM offering a BASIC with 42 statements, 32 built-in functions, two dimensional arrays, and strings of up to 80 characters. A key benefit over the PC-1 was the expansion port on the back of the unit which allowed both RAM and ROM expansion, and an RS-232C interface. The machine expanded the printer and cassette functionality as well. This model corresponds to the Sharp PC-1500.

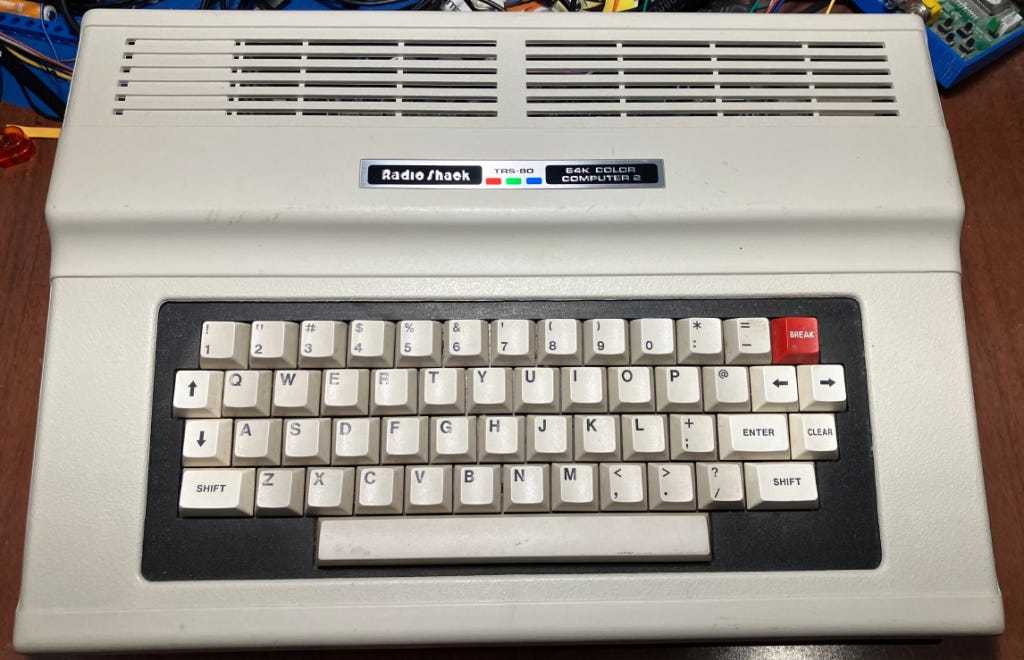

The Color Computer 2 was released in 1983 at a price of $159. The discrete circuitry within the CoCo was replaced by ICs and the motherboard was redesigned, the case and power supply were made a bit smaller, the keyboard was improved, and the overall styling was changed.

The TRS-80 Pocket Computer 3 was released in 1983 for $99.95 and corresponds to the Sharp PC-1251. This was the smallest of Tandy’s Pocket Computers, and measured just three eighths of an inch thick, five and 5/16 wide, two and 3/4 tall. This model could be used with Sharp’s micro-tape drive and thermal printers, and these were offered in a dock.

The Pocket Computer 4 corresponds to the Casio PB-100 and was the lowest priced pocket computer that Tandy offered at just $69.95. Like those before it, it offers a single row LCD, but here with just 12 characters. This model also offered both cassette and printer connection. Here, however, the computer was powered by two CR2032 lithium cells offering 360 hours of use. This model would automatically power off after seven minutes of inactivity to save battery. The BASIC variant in use on the PC-4 was limited, and it allowed for strings of eight characters, but arrays could be expanded to nearly the entire memory space of 1568 bytes, and the $ variable could hold 30 characters. The PC-4 also had a 1K RAM memory module available for an additional $19.95.

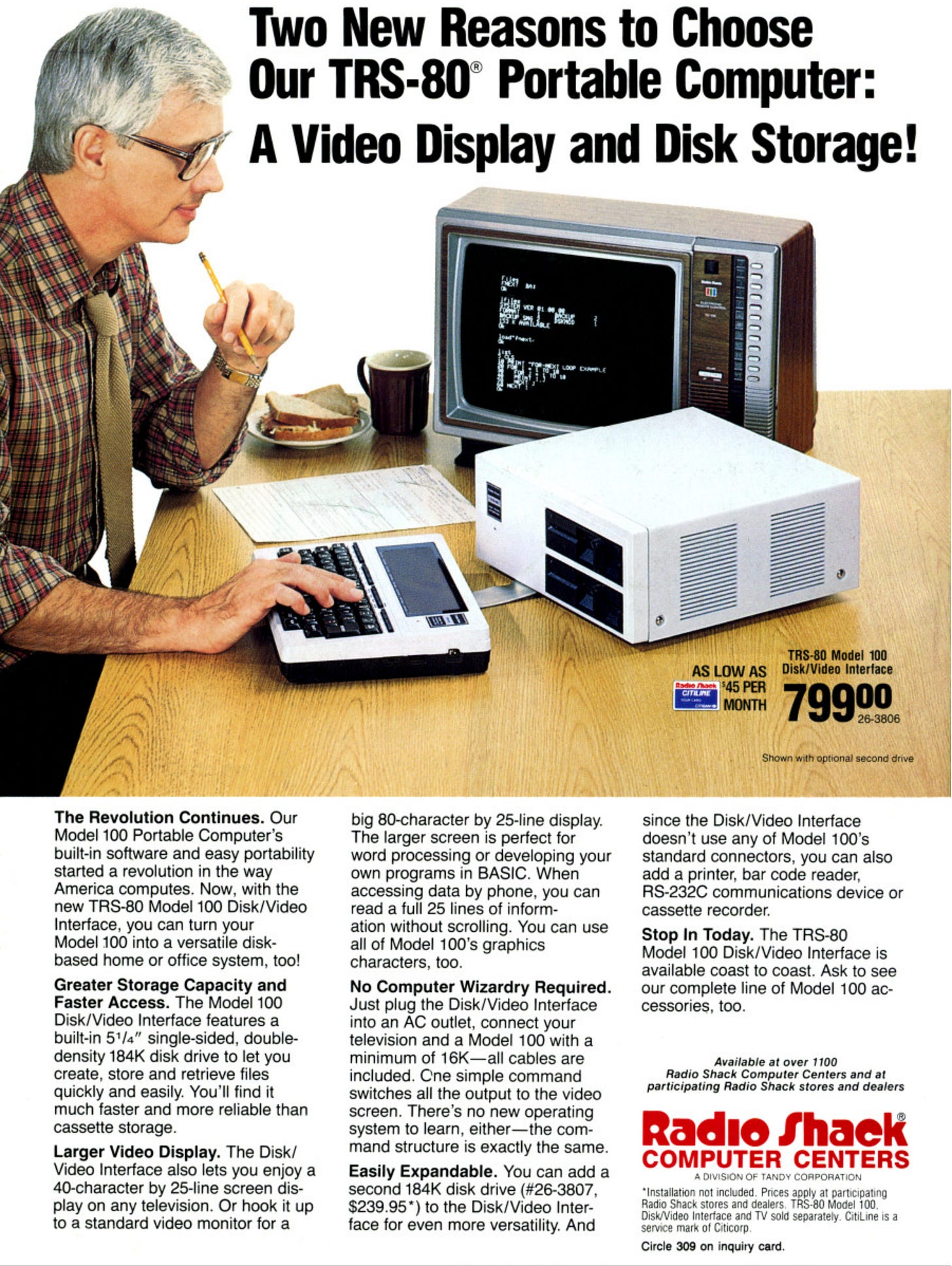

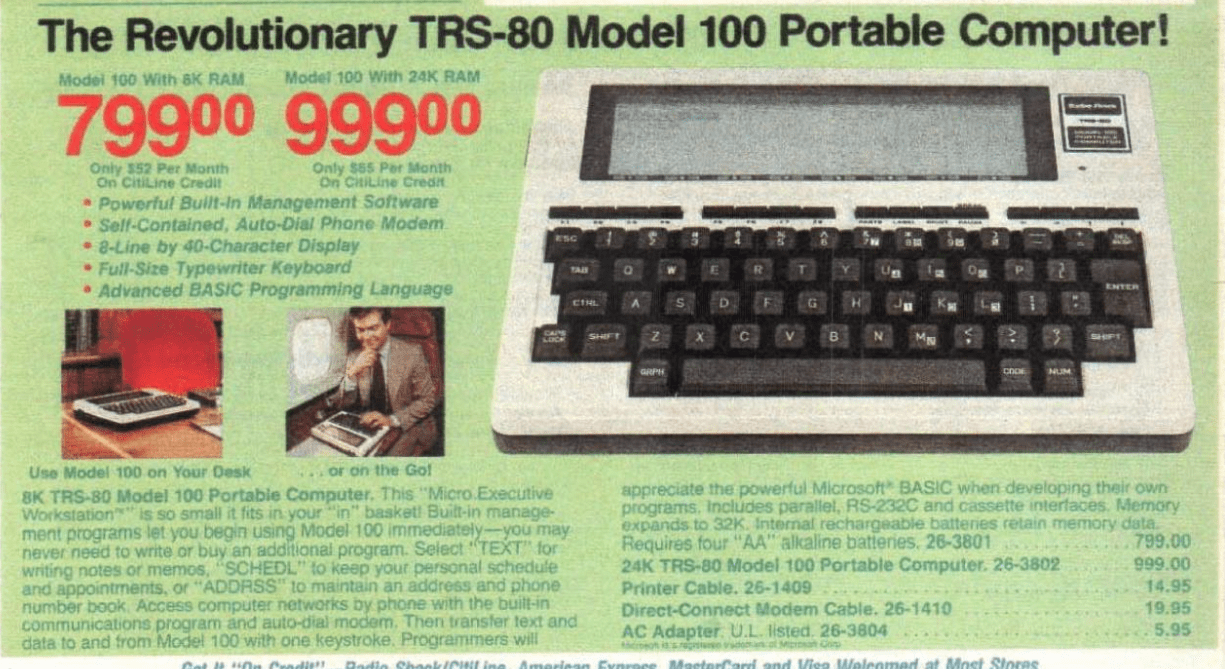

What became the TRS-80 Model 100 began at Kyocera as the Kyotronic 85, and was among the first “laptop computers” to be a commercial success. The primary design of the computer was carried out by Junji Hayashi, Rick Yamashita, and Jey Suzuki with Kazuhiko Nishi being involved in management. As the machine was being developed, Nishi reached out to his friend Bill Gates at Microsoft for some software development and stated that the machine would have four lines of twenty characters. With that screen real estate, Gates wasn’t at all interested. A short time later, Nishi contacted Gates once more, but this time stated the machine would have eight lines of forty characters or 240x64 pixels for graphics. Now, Gates was, according to him, pretty fascinated. According to BYTE, Bill Walters was involved in Tandy’s adaptation of the Kyotronic 85.

From the start, the entire team knew that this wouldn’t be a slimmed down desktop. Both battery life and ease of use were serious restraints. Yet, despite those restraints, the machine included a 32K ROM, up to 32K RAM, cassette interface, a built-in 300 baud modem, RS-232C, parallel port, bar code reader port, and a real time clock. This machine could even accommodate bubble memory for RAM expansion allowing a total of up to 40K RAM (unofficial), and an option ROM could be installed bringing the ROM total to 64K. All of this was powered by four AA batteries providing 20 hours of run time. For the CPU in this machine, Kyocera chose the 8080 compatible 8085 running at 2.45MHz manufactured on a 3 micron CMOS silicon-gate process by Oki, which came in a plastic DIP with 40 pins. This chip was chosen for power efficiency, good thermals, and its use of a single 5V supply.

So, what could be done with this machine? Given that it had a full-size, full-travel keyboard and a competent text-editor, it could be used for typing. The editor, TEXT, even supported some WordStar keybindings. With the standard ROM, users also had access to a calendar/schedule (SCHEDL), an address book (ADDRSS), a BASIC interpreter, a simple file manager, and a dialer (TELCOM) for the modem. Third party and/or custom applications could be loaded via cassette or bar code reader. With an add-on ROM, the machine could run TS-DOS which would then allow for the saving/loading of files to/from a PC via a null-modem cable and DeskLink software.

Pricing for the Model 100 ranged from $799 to $1134 depending upon the RAM selection with the cheapest at 8K and the most expensive at 32K. Given that the RAM doubled as data storage, getting the highest possible RAM configuration one could afford was essential for this machine. Additionally, making sure that the NiCD battery backup was charged was likewise essential as otherwise, as soon as the AA batteries were depleted all would be lost. Of course, the designers thought about this. The machine could be powered by the mains, and a low battery warning light would be illuminated when the machine had about 20 minutes of runtime left.

The Model 100 shipped with two manuals. One was a large spiral bound of 200 pages that was roughly the same size as the computer. The other was a pocket sized 40 pager that was more of a quick reference.

Many people know of the TRS-80 Model 100, but very few know of the Kyotronic 85, Olivetti M10, or the NEC PC-8201. Within Japan, this computer wasn’t much of a success, but in the USA, it sold quite well. This computer was particularly popular among members of the press given its competent text editor and modem. With expandability including ROM, RAM, printer, cassette, disk drives, and output to a TV, the machine was compact powerhouse in a time when this was rare. It certainly didn’t hurt the product that floppies used with the disk drive expansion utilized the FAT filesystem. For BillG, this was the last project on which he wrote any significant amount of code, and what an ending! That he and Suzuki could pack so much into so little space shows an understanding of both software development and the 8085 CPU that is truly impressive. He apparently enjoyed the little computer saying it was “in a sense my favorite machine”, and he used a Model 100 from around the time of release until the 27th of January in 1987 when he switched to using a Model 200.

The TRS-80 Model 4 that shipped in May of 1983 was a far cry from what was dreamed of when it was called Project R. The initial goal was for this machine to be an improved Model III with an 80x24 character display, 128K RAM, a detachable keyboard with control and function keys, support for graphics, sound, and an 8bit Z80 CPU at 4MHz with the option to upgrade to a 16bit Z800 CPU. What actually shipped was another all-in-one unit with a Z80A at 4MHz, but it could be switched to 2MHz for Model III mode. The system had 14K ROM, 64K RAM (upgradeable to 128K), an 80x24 primary display mode, MS BASIC 5.0, two 5 and 1/4 inch floppy disk drives (184K), cassette, parallel, and RS-232C. The TRS-80 Model 4D was essentially the same machine but with double-sided 368K drives and DeskMate. The 4P was essentially a Model4 with a small boot ROM, no Model III ROMs, no cassette interface, and poor support for external drives. The advantage of the 4P was its luggable form factor. All of these changes from the original vision were, according to Frank Durda, decided for two reasons. The first was the schedule for launch. The second was parts availability. The Z800 saw six years of delays, but it eventually did launch as the Z280. By that time, the computer was old enough that offering the upgrade would have been pointless and the Model 4 was no longer in production. So, while Bill Schroeder chain smoked, he, Roy Soltoff, and Durda sat around working out the specifics of the machine, and given the aggressive launch timeline from the project’s start in the autumn of 1982, they moved the Model 4 into a Model III case, dropped the Z800 plan, dropped most of the sound and graphics upgrade plans, and really only achieved the faster Z80 plan and 80x24 character display. The Model 4 could, unlike all of its predecessors, run CP/M unmodified, but it shipped with TRSDOS 6 (rebranded LDOS 6). None of the Model 4 machines sold particularly well; an unfitting end to the original TRS-80 line that had been such a success.

The IBM PC model 5150 had launched on the 12th of August in 1981, and the 5150’s first shipments were in October that year. In the 5150’s first year, the PC generated $1 billion in revenue. By late 1982, IBM was selling around 200,000 PCs per month, and then IBM introduced the IBM XT model 5160 on the 8th of March in 1983. Tandy’s market share had dropped to an estimated 23.3% with essentially all of their losses having gone to IBM. To make things worse, Compaq had already begun gobbling up press attention. Tandy’s response to all of this was the TRS-80 Model 2000 introduced on the 30th of November in 1983.

On paper, the Model 2000 was a better machine than the 5150. It shipped with an Intel 80186 at 8MHz, up to 768K RAM, up to a 10MB hard disk, two 720K floppy disk drives, an 80 by 25 character display capability, graphics display of 640x400 with eight colors, optional 80187, and it ran MS-DOS 2 or XENIX. The use of an 80186 provided the Model 2000 with a performance uplift of three to six times the 5150 depending upon the application. With the Model 2000, Tandy left all of their prior styling behind, and they chose to use more of the IBM’s look. It came in an off-white case, with an off-white keyboard, and an off-white display. All three pieces were separate units, and the computer itself could rest on a desk or be rotated 90 degrees, and the name plate could be rotated to match the orientation. Another departure, this was officially the Tandy TRS-80 Model 2000 with no “Radio Shack” appearing anywhere on the machine. As for displays, a customer could opt for either a green phosphor display for $250, or an RGB display for $799. The base model with no color graphics adapter and a green phosphor display would set a buyer back by $2999, a unit with a graphics adapter and color display was $4197.

I said “on paper” the Model 2000 was better than the IBM PC. The issue here was that the 5150 had set a standard. While both machines ran MS-DOS and used similar BIOS, the similarities ended there. Most PC applications that were in high demand were simply incompatible with the Model 2000. Primarily, if an application were written for the BIOS and MS-DOS and didn’t access hardware directly, it was compatible, and it otherwise wasn’t. This meant that the PC version of Lotus 1-2-3, WordStar, and most of Ashton-Tate’s offerings were incompatible with the Model 2000 (though, I believe the 2000 did receive a port of Lotus 1-2-3 [I’d love more information on that]). Also, because the Model 2000 utilized higher capacity disks, it could read most IBM floppies, but it couldn’t write to them. The Model 2000 also had no real compatibility with prior machines in the TRS-80 line.

The Tandy Model 2000 was neither the only semi-compatible machine at the time nor the first, and fully compatible machines were available by the time the Model 2000 made it to market. Ed Juge, director of computer marketing at Tandy, stated about the Model 2000:

The reason we did what we did was that we didn’t like the idea of just going out and copying what someone else was doing. It was not our thing. We knew we could either clone this computer or we could build the best damn MS-DOS machine our engineers could design — the state of the art in hardware. I had nagging doubts, but not enough to argue with anybody.

Within six months, they knew they’d made a mistake, but they had another machine in the works before the Model 2000 had been announced.

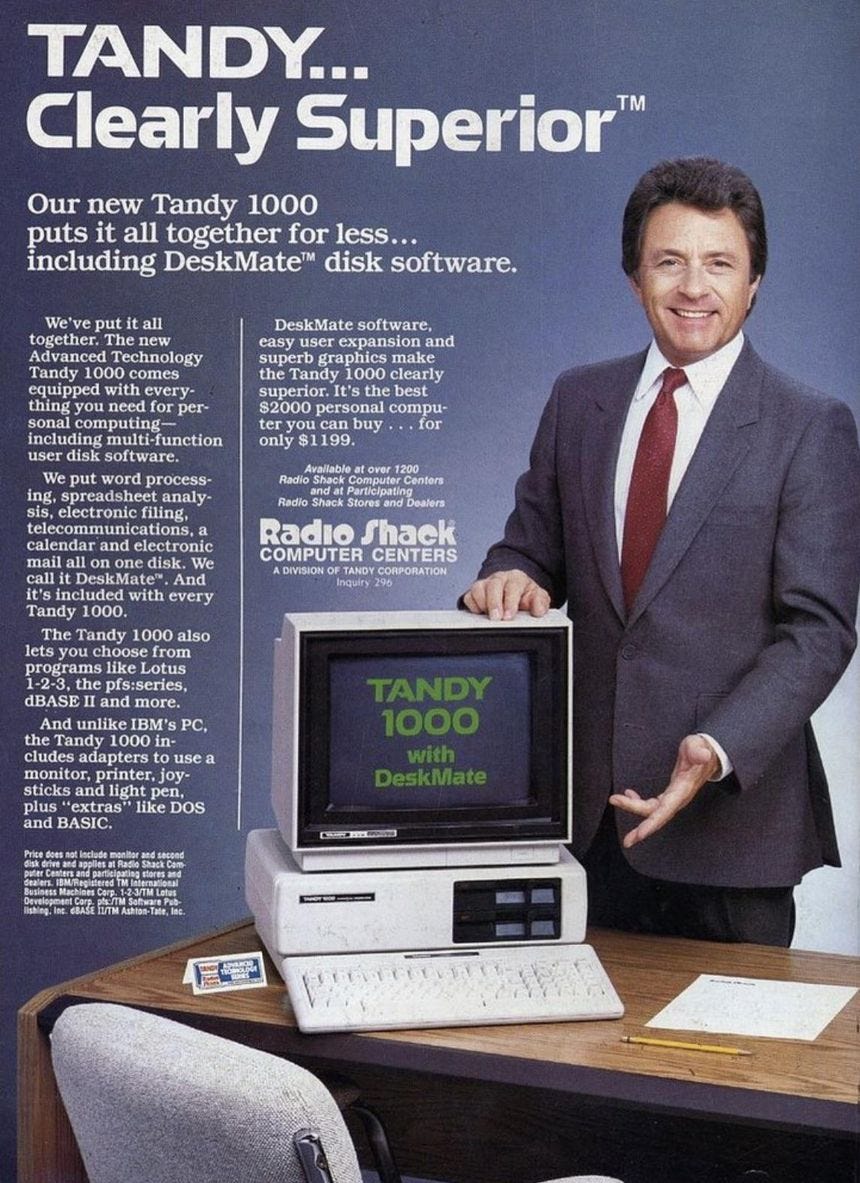

In September of 1983, John Roach had gathered the company’s engineers in a conference room, and said: “Gentlemen, this is our next product. It is codenamed August. I hope it’s obvious what that means.” This was the Tandy 1000, and it was fully IBM PC compatible while supporting the PCjr’s graphics. The Tandy 1000 (that’s the official name, no TRS-80 and no Model) integrated many technologies that would normally have required expansion cards, and this allowed it to take up less desk space than a PC or XT while lowering costs for the buyer. For the keyboard, Tandy used the same that had shipped with the 2000. The CPU in Tandy’s machine was an Intel 8088 clocked at 4.77MHz, and it shipped with 128K RAM standard (expandable to 640K). Every Tandy 1000 also included monochrome and color adapters, TV output (required a separate RF adapter), a double-sided double-density 5.25 inch disk drive (360K-byte capacity), a three-voice sound generator, a built-in speaker and audio output jack, a parallel printer adapter, twin joystick ports, a PCjr compatible light-pen interface, and three expansion slots. The expansion slots were standard 8bit ISA, but the case of the Tandy 1000 limited card length to a maximum of 10 inches. Where things become less-than-fully-compatible is regarding some ports; the Tandy 1000 used a proprietary 8-pin DIN connector and keyboard from the 2000, the joystick ports were 6-pin connectors from the Color Computer, and it used a card-edge parallel printer port from the TRS-80 line rather than the DB-25 port that had become standard in the rest of the industry.

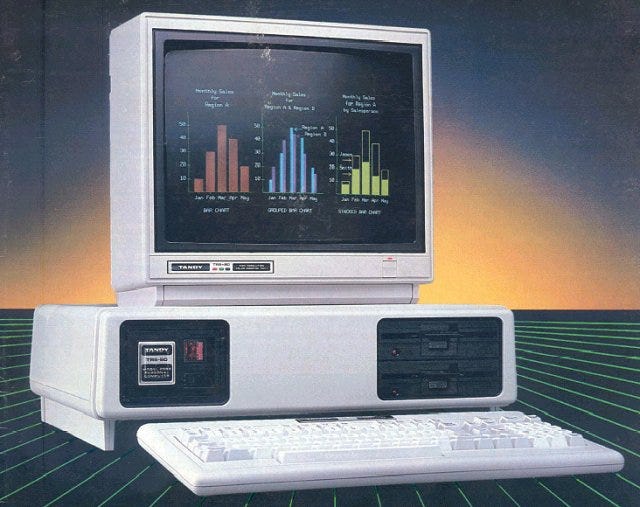

The video adapter is the true advantage of the Tandy 1000 providing compatibility with both the PC and the PCjr. This was accomplished via a video gate array IC that worked with a Motorola 6845 CRT controller. In character mode, this delivered a resolution of 80x25 with sixteen foreground and sixteen backgrounds colors available unless blinking were used which would cut the background colors to eight. When the system was in graphics mode, low-res offered sixteen colors at 160x200, medium resolution offered sixteen colors at 320x200, and high resolution was four colors at 640x200. The machine was also capable of all standard CGA modes. One major problem with the PCjr was that the sharing of memory between the graphics processor and CPU yielded considerable idle time for the CPU. Tandy set about eliminating as much idle as possible and managed to achieve four accesses every microsecond (two for CPU and two for graphics). This improved more if a machine was expanded to 256K RAM and DMA was used.

On the software side of things, the Tandy 1000 shipped with MS-DOS 2.11 and Tandy DeskMate (though it was compatible with Windows 1, 2, and 3.0). When it was released in November of 1984, it was priced at $1199 providing exceptional value. It was less expensive than IBM, had integrated ports that would otherwise have required expansion cards, and it improved on both the IBM PC and the PCjr. It was immediately successful. The success of the Tandy 1000 meant that the graphics and sound it offered became known as “Tandy Graphics” and “Tandy Sound” despite having been a standard originally created by the PCjr. As for why this mattered, let’s compare CGA to Tandy Graphics.

The Tandy 1000 likely saved Tandy Corporation just as the TRS-80 Model I had. While Tandy Corporation wouldn’t achieve the kind of market dominance that they once enjoyed, the Tandy 1000 would claim nearly 10% of the market for itself within two years. Tandy had been humbled by IBM, but they weren’t done. Like so many successful companies, they pivoted to where the market had gone and succeeded.

My dear readers, many of you worked at, ran, or even founded the companies I cover here on ARF, and some of you were present at those companies for the time periods I cover. A few of you have been mentioned by name. All corrections to the record are sincerely welcome. Please feel free to leave a comment.