The History of Caldera, Part 2

SCO and Litigation

This is the second entry in a two part series on Caldera. If you’ve not already, you may be interested in reading Part 1, which covers the origins of Caldera.

Following the release of Caldera OpenLinux, the breakup of Caldera, and the on-going lawsuit, Caldera Systems wasn’t slowing down. At the time of incorporation on the 21st of August in 1998, Caldera Systems took over the Linux business and all of the existing Linux customers. Ransom Love was the President and CEO, and Caldera Deutschland was the Linux development center. Caldera Systems was intent on developing Caldera OpenLinux and marketing the system as a viable commercial operating system. To support this effort, the company engaged in corporate training, support, and services surrounding the OS. The first in those efforts was the Caldera Linux Administration Course. This was offered by Caldera Systems Educational Services in partnership with centers of education around the USA and Europe and attempted to be distribution agnostic.

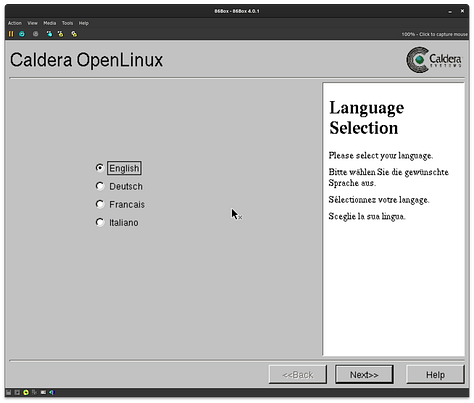

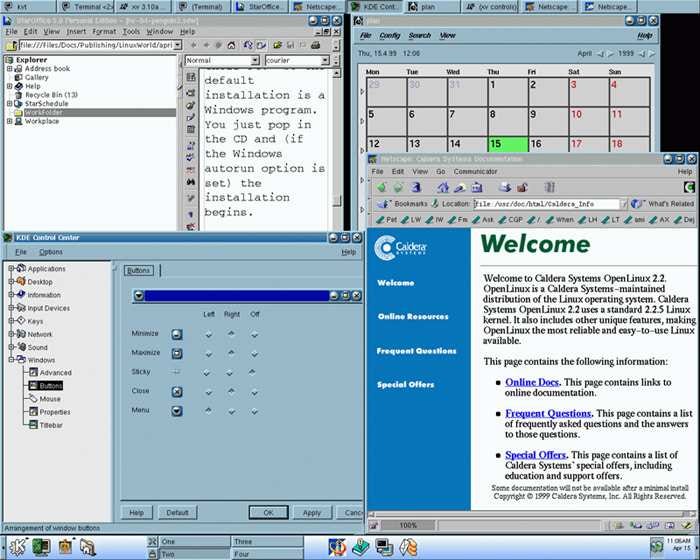

Caldera OpenLinux 2.2 was released on the 19th of April in 1999 with Linux kernel 2.2.5. This was a big release not just for Caldera, but for the Linux world more generally. This version was the first Linux distribution to make use of kernel 2.2, and it was the first distribution to be self-hosting with glibc2 instead of libc5. Caldera had partnered with Trol Tech on getting Qt and KDE to be first class citizens on Linux and this showed. The first evidence is in the new installer called Lizard (Linux Wizard). The installation was bootable, and would automatically bring the user to a fully graphical installer. OpenLinux 2.2’s installation could also be started from within Windows. In this case, upon insertion of the CD-ROM, Windows would launch the installer. When the user chose to continue with the install, the machine would be put into DOS and Partition Magic would be run. This would shrink the Windows partition and create the partitions for OpenLinux. Upon reboot, the user would then be greeted by the same installer as those who’d booted directly from CD. The main difference for Windows users is that they’d be using BootMagic instead of Lilo as their bootloader allowing them to boot into either Linux or Windows.

For these images, I was using 86Box with a Pentium II, 256MB of RAM, a 1GB HDD (resized to 2GB after the images above were taken, and the virtual CD-ROM speed was increased to 52x because the original configuration was… too slow), a SoundBlaster 16, an NE2000 ethernet adapter, and a Voodoo3 chipset. This selection was made due to my being very familiar with it (I have such a machine in my basement), and knowing that everything should work with Linux distributions of this era. I was amazed that Caldera could use the Voodoo3 considering it was released the same month that 2.2 was released. I was surprised too by the ability of the installer to probe hardware both automatically and upon request for automatic configuration. The inclusion of Tetris while waiting for the install to complete is a super nice touch. Despite package installation starting before the full configuration is completed, I still had some to kill. The particular implementation of Tetris does have fast drop and slide, but the slide mechanic doesn’t always work which led to several unfortunate gaps in my falling blocks. The installer even waits for you to click “Finish” rather than interrupting your play.

This was easily the most enjoyable system installation ever, and more systems should copy this! At this point, there was a bug in Lilo (the Linux loader, or boot loader) where systems with drives of more than 1024 cylinders could fail to boot. Reports from the time of the release of COL version 2.2 mention this bug being present, and I was absolutely able to recreate this. For many new users to Linux this would have been catastrophic. The support offered by Caldera, however, would have made this much nicer. In my case, I booted up the virtual machine with tomstrbt, and then chrooted into the OpenLinux installation, and reinstalled lilo with linear addressing.

mount /dev/hdc1 /mnt

mount /proc /mnt/proc -tproc

chroot /mnt /bin/sh

/sbin/lilo -C /etc/lilo.conf -lThe response to this release was good with positive reviews from LinuxWorld, Linux Journal, Linux Today, and other tech press. It was good enough that Caldera’s website which offered free downloads of the system were taken offline temporarily due to high traffic. The basic release was available free of charge with higher tiers offered for $50 or $100 (around $92 or $184 in 2023). Depending upon the version purchased/downloaded, a user would receive Linux, KDE 1.1, Glibc2.1, PowerQuest Partitioning, Boot Magic 4, WordPerfect 8, Samba, COAS (Caldera Open Administration System: a Python-scriptable, control panel-style administration tool with both GUI and textual interfaces), NetWare Client with PAM, BRU backup tool, StarOffice 5, Netscape Communicator, DR-DOS 7.02, XFree86 3.3.3, Applixware Office Suite, IBM ServeRAID support, Compaq Smart2 RAID support, Mylex RAID support, WINE, frame buffer support, Qt 2.0, development libraries and environments, and relevant documentation. The KDE environment also included themes that would allow for the default KDE look-and-feel, Macintosh, Windows, or BeOS. All purchased Caldera versions also included ninety days (up to five incidents) of technical support with twenty four hour, seven days a week email support, and fee-based phone support was also available. All support came with a guarantee of one-hour or less response time. This release required at least an Intel 80386, 16MB of RAM, and a 350MB HDD.

Following the positive reception of this release, Caldera began looking for more investors. Initially, they just got turned down quite a bit. IBM, Intel, and many of the other megacorporations all refused, and this could have been due to the lawsuit, but that’s not known. Funding was eventually found from Sun, Citrix, SCO, Chicago Venture Capitalists, Egan Managed Capital, and Ensign Peak. Love cites Red Hat’s successful IPO as one of the largest reasons for Caldera having been able to secure funding at all, and this seems like sound reasoning.

Version 2.2 was followed by 2.3 in August with kernel version 2.2.10, and the funding from Citrix and Sun showed up with video and audio conferencing tooling as well as quite a bit of Java support and tooling. The boot bug and other issues were also remedied. In autumn of 1999, Caldera helped fund and establish the Linux Professional Institute which began operation on the 25th of October.

Following the fresh investment and new release, Caldera Systems reincorporated on the 3rd of March in 2000 in Delaware, and the company had their IPO on the 21st of March in 2000 with symbol CALD. The first day of trading was great, but fell far short of other Linux IPOs. The opening price was $14 (around $25 in 2023) and the closing was $29.44 (about $52 in 2023) and gave the company a market cap of $1 billion (about $1.78 billion in 2023). The organization of the IPO was handled by Robertson Stephens, Bear Stearns, Wilt, and FSVK.

In late September of 2000, Caldera released OpenLinux eDesktop 2.4 for $39.95 (around $71 in 2023). This version improved the distribution in most regards, and it added webmin. Webmin was a web-application version of COAS allowing remote administation. The system also included Kpackage for GUI software installation from RPM repositories. In addition to all of the previously included proprietary software, 2.4 also included Omnis Studio for web developers, Cameleo Lite for graphics, Moneydance personal finance, and even more Java tooling. The tech press once again had favorable reviews.

On the 2nd of August in 2000, Caldera announced its intention to acquire the Santa Cruz Operation’s server software division and professional services division. SCO had just posted a loss of $10 million (about $17.8 million in 2023) in its third quarter following other down quarters. SCO would gain seventeen and a half million shares of Caldera (around twenty eight percent of the company) in addition to $7 million in cash (about $12.5 million in 2023). The Canopy Group would further lend SCO $18 million (around $32 million in 2023). On the surface, this deal makes perfect sense. Caldera was a major Linux player, but Red Hat was still holding around fifty percent of the Linux market. SCO held the majority of UNIX market, but that market was constantly shrinking due to the rapid rise of Linux and NT. Combining their efforts would give both companies a shot at survival. On the other hand, SCO had spent some time speaking out against Linux in favor of their own UNIX platform, and this hadn’t exactly made the company popular in within the Linux community (despite their recent turn to Linux services).

In the press release for this acquisition, Caldera stated that its intent was to offer the first comprehensive Open Internet Platform. This would combine Linux and UNIX server solutions and services providing software developers a single platform, and providing commercial customers a single system for everything from thin clients to mainframes. The newly combined entity was named Caldera International and remained headquartered in Orem, Utah. The CEO remained Ransom Love, but David McCrabb (former CEO of SCO) was President and COO. After many months, the SEC approved the deal and the acquisition was completed on the 7th of May in 2001. This deal went on for so long that Tarantella’s fortunes began to rapidly decline, and Caldera was able to negotiate the purchase of that former SCO entity as well. Caldera was much smaller than SCO, much younger than SCO, and this merger would dramatically change Caldera. Caldera had traditionally made money through the sales of software and services with more stress placed on services. They also added proprietary software to their distribution to add value. The company innovated and held some of those innovations for premium editions. They also engaged in certifications (both hardware/software certification, and in professional training and certification) and subscription services. This did not initially change with the SCO acquisition.

The first quarter after the completion of the merger was rough. In the intervening time, SCO’s sales had essentially halted. The sales and marketing teams were giving rosey projections for the end of the quarter, but those projections weren’t accurate. The information was filtered through SCO’s middle management, and no one wanted to provide bad news to the new owners. As a rather immediate result at the end of that quarter, the entire middle management layer of the company was fired. The executive team then started to fly around the world meeting with customers, OEMs, and ISVs. Their intent was to gather information as to the true state of their business and their business’s relationships. For the first year, the headcount at Caldera International had gone from 650 to about 395, revenues which had been falling were leveled off, the Dot Com crash had begun, and Caldera engaged in serious cost cutting amounting to nearly forty percent reduction.

Despite a reduction in headcount and despite severe reductions in cost, Caldera wasn’t profitable and had never really been profitable. For the revenue that Caldera had coming in, something around seventy percent of that revenue was from SCO’s UNIX offerings. Caldera needed to establish itself as the Linux brand in much the same way that SCO had become the UNIX brand. How one would go about making a single distribution “Linux” is not immediately obvious. For Ransom Love, however, one thing was very obvious. Major Linux vendors could all save money by not duplicating efforts. If Linux vendors could share a common base then all would stand to benefit. For Caldera, this would then allow them to add value with things like Lizard, COAS, SCO UNIX, NetWare, DR-DOS, and backwards compatibility without spending as much time and money on underlying Linux infrastructure.

John Terperstra left Turbo Linux and joined Caldera in 2000, and he started talks with SuSE, Turbo Linux, and Connectiva around just such an idea. In August, Rick Becker of Compaq arranged a meeting in Munich to try and further this discussion. SuSE fell out. So, Caldera turned to IBM, and a meeting was setup in Barcelona. A basic understanding was reached, but true agreements didn’t form until after the appointment of a new CEO at SuSE, Gerhard Bertcher. Meetings followed in Utah, then Atlanta, then in New York, then in London. Love then had two rounds of meetings each with Red Hat and Mandrake. On the 29th of May in 2002, United Linux LLC was formed. It was publicly announced the following day. Members signed two contracts. One was the Master Transaction Agreement, and the other was the Joint Development Contract. Together these contracts assigned the intellectual property rights of code to United Linux and granted each member royalty-free use of all of that intellectual property with a fully open source licensing scheme. Finally, these contracts set an arbitration agreement for any disputes. An internal beta was circulated among members on the 14th of August in 2002 with a public beta following on the 25th of September. United Linux 1.0 was released on the 19th of November in 2002. This distribution was primarily based upon SuSE Linux and the Linux Standard Base. United Linux was somewhat successful. IBM and AMD quickly partnered with United Linux LLC, and the Linux Professional Institute began using United Linux as their distribution for training and certification. SuSE was providing engineering expertise, Caldera brought a global support network and vendor relationships, and things looked promising, but the market didn’t care for it partially due to per-seat licensing, which was very… non-Linux-like.

During the merger and the development of United Linux, the board had become decidedly SCO heavy, and the Tarantella members of the board typically sided with SCO giving them a majority in any disputes. They ousted Love citing him as the reason for falling revenues and not the wider market conditions. The board then made Darl McBride the CEO of Caldera International. At this point, the focus of Caldera became UNIX. On the 26th of August in 2002, he announced in Las Vegas that Caldera would be renamed to The SCO Group. The company’s stock symbol was also changed to SCOX, and the company relocated to Lindon, Utah.

While McBride pivoted the company to UNIX and was essentially continuing the sales of XENIX, he was extremely interested in the intellectual property of the company he was now running. He considered quite early taking claim of some of the code within Linux, and Love advised him quite strongly against doing so. On the 6th of March in 2003, SCO filed a lawsuit against IBM. This suit claimed that IBM had stolen portions of UNIX and incorporated them into Linux and that IBM had breached its contract with SCO in Project Monterey. They were seeking compensation of “no less than $1 billion.” Somewhat humorously, The SCO Group was now attacking Linux, a product that its direct corporate predecessor had helped fund and develop in rather significant ways, and a product which SCO still sold. Red Hat filed a lawsuit against The SCO Group on the 4th of August in 2003 looking for a permanent injunction against SCO’s anti-Linux campaign. On the 3rd of March in 2004, SCO filed two more lawsuits, and these were aimed at end users AutoZone and Daimler Chrysler. In the case of AutoZone, SCO claimed that the company was using code derived from UNIX in Linux. In the case of Chrysler, SCO claimed that Chrysler had violated the terms of its UNIX software agreement. As the IBM case continued over the course of years, SCO increased its requested compensation for damages to $5 billion, and the company suggested a license fee of $1399 per CPU for Linux. The issue here is that IBM had considerable resources and a powerful legal team. The case fell apart as IBM proved that the supposedly misappropriated technology didn’t exist, and when asked to provide direct evidence of their claims, the SCO Group’s assault essentially crumbled. In an even more humorous turn of events, Novell announced that SCO didn’t own UNIX. SCO then attempted to sue Novell for slander of title, which resulted in the courts deciding on the 30th of March in 2010 that Novell was indeed the owner of UNIX.

Had these lawsuits not begun, the financial prospects of SCO were actually fairly good. Revenues for 2003 were around $79 million with a profit of $3.4 million. Unfortunately, in 2004, this had all gone the other way with just $11.2 million in revenue and a loss of $7.4 million of which $7.2 million was legal costs. These fortunes never reversed. On the 14th of September in 2008, SCO filed for bankruptcy. The company then began attempting to sell assets. UnXis (now Xinuous) bought the UNIX products and the existing service contracts for those products. McBride himself bought the company’s mobility assets and started a company called Shout TV which sold to MMA Global in 2018. What was left of SCO renamed itself to The TSG Group and continued with litigation. A settlement was finally reached on the 8th of November in 2021 with IBM paying $14.25 million for breach of contract in relation to Project Monterey. TSG agreed to give up all future claims against IBM. Unfortunately, on the 31st of March in 2021, Xinuous filed a copyright infringement and antitrust lawsuit against IBM in which it claims that IBM stole intellectual property and used that stolen property to build and sell a product to compete against Xinuous. In this case Xinuous claims that it was OpenServer and UnixWare that were stolen and used to make AIX, and that via Red Hat, IBM conspired to keep Xinous out of the market.

This is probably the third or fourth time you’ve mentioned Novell in one of your articles. Have you considered writing a post about them and their impact on computing history?

Interestingly, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China was hit by a ransomware attack a few months ago and part of their ability to recover quickly was owed to a key part of its trading system being house on a Novell file server that was immune to the attack.