The Osborne Computer Corporation

From boom to bust in a few short years

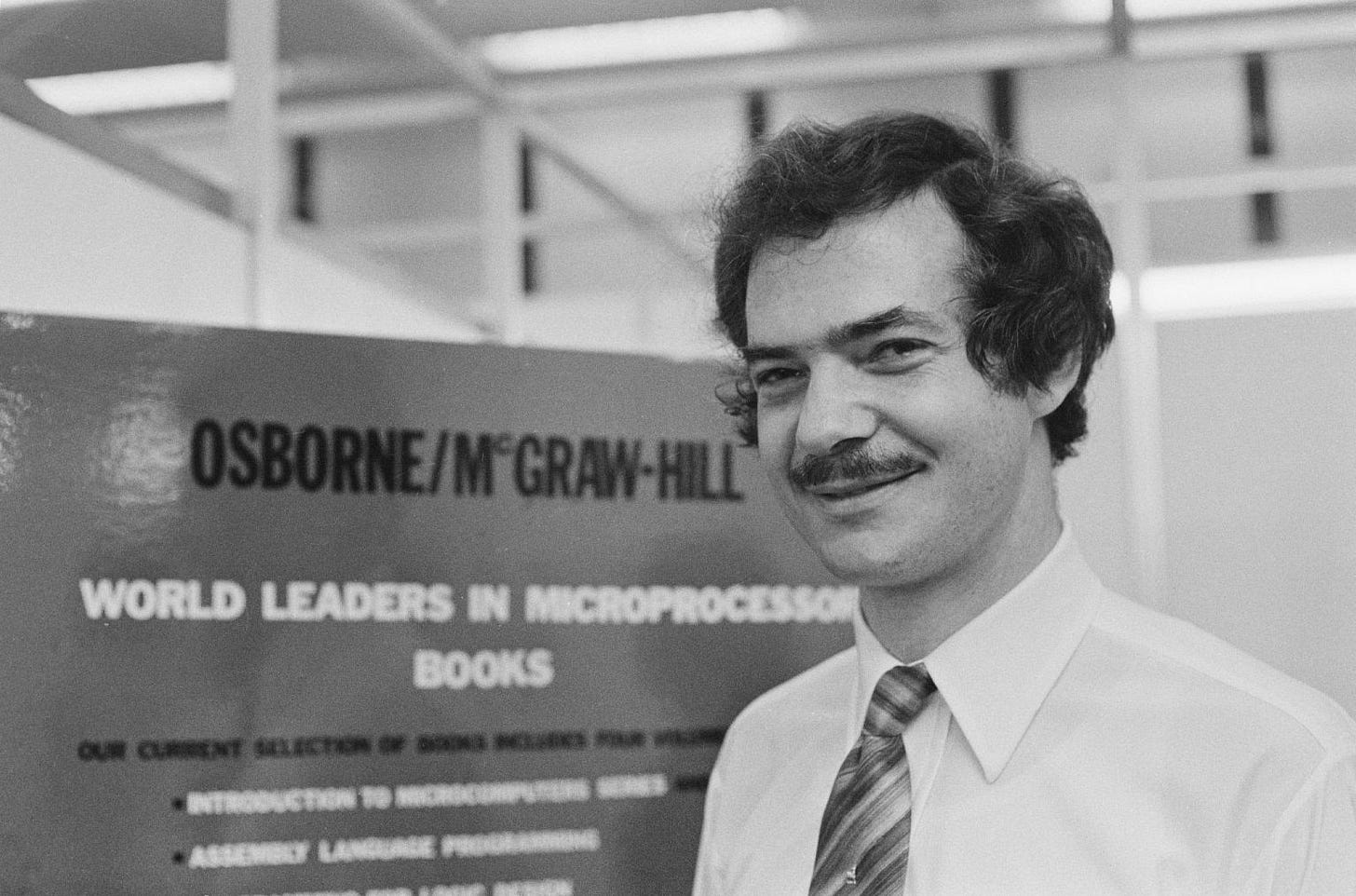

Adam Osborne was born on the 6th of March in 1939 in Bangkok in the last days of Siam. His father, Arthur, was British and his mother, Lucia Lipsziczudna, Polish. Osborne’s father was a fascinating man. He spoke many languages including Thai, Arabic, and Tamil, was well versed in Eastern philosophy and religion, and his life was a quest for truth and meaning. He was teaching at Chulalongkorn University and his family was with him. Arthur’s wife, two daughters, and son (Adam) left for Tiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu, India in September. Not long after, Japan invaded Siam, and Arthur was interned for the next four years. After the Japanese surrender, Arthur joined his family in Tamil Nadu.

Osborne’s early life was spent at an ashram. An ashram is something like a Hindu monastery, and for the Osborne family, home at this time was the ashram of Sri Ramana Maharshi, the Sri Ramana Ashram, near Arunachala. This setting gave his childhood quite a bit of freedom, nurtured his creativity, stimulated his mind, and provided him self-confidence. It also meant that his first language was Tamil, and his English became distinctly Indian.

Adam Osborne went to Presentation Convent School in Kodaikanal until 1950 when the Osbornes returned to England. The transition was difficult for Osborne. He changed his style of dress, worked to shed his accent, and endeavored to become more British. I cannot imagine that this would have been easy for a child accustomed to freedom, but he went to a Catholic boarding school in Warwickshire for a few years and then began attending Leamington College for Boys in 1954. He earned a degree in chemical engineering from the University of Birmingham in 1961, and he then moved to the USA and earned his PhD from the University of Delaware in 1968. It was while working on his PhD that Osborne learned how to write software. The combination made him an attractive hire for Shell Development Corporation in Emeryville, California.

Osborne’s older sister, Katya, described him as curious and said of him “His interests seemed to constantly shift. A fascination with poetry gave way to science. Science gave way to engineering. Adam wanted to understand and master it all.” Others have described him as handsome, charming, intelligent, quick witted, persuasive, ambitious, restless, and arrogant. The adjectives of charming and arrogant do not exactly get on, and I am led to think that it may have been Osborne’s distinct upbringing that led to the perception of arrogance. Having been raised in a place where nearly all questions were treated as valid and where a young child could walk up to an esteemed religious leader and in familiar language address him with any question, one can easily imagine the type of confidence that child would later possess. He was simply never taught that one should shrink before power. This arrogance or assertive confidence may have been the reason for his firing at Shell. Apparently, he had frequent disagreements with his superiors.

Upon leaving Shell, Osborne took up freelance technical writing, and one of his first jobs in this respect was writing the documentation for the new Intel 4004. Another was The Value of Power written under contract for General Automation in 1972 about minicomputers.

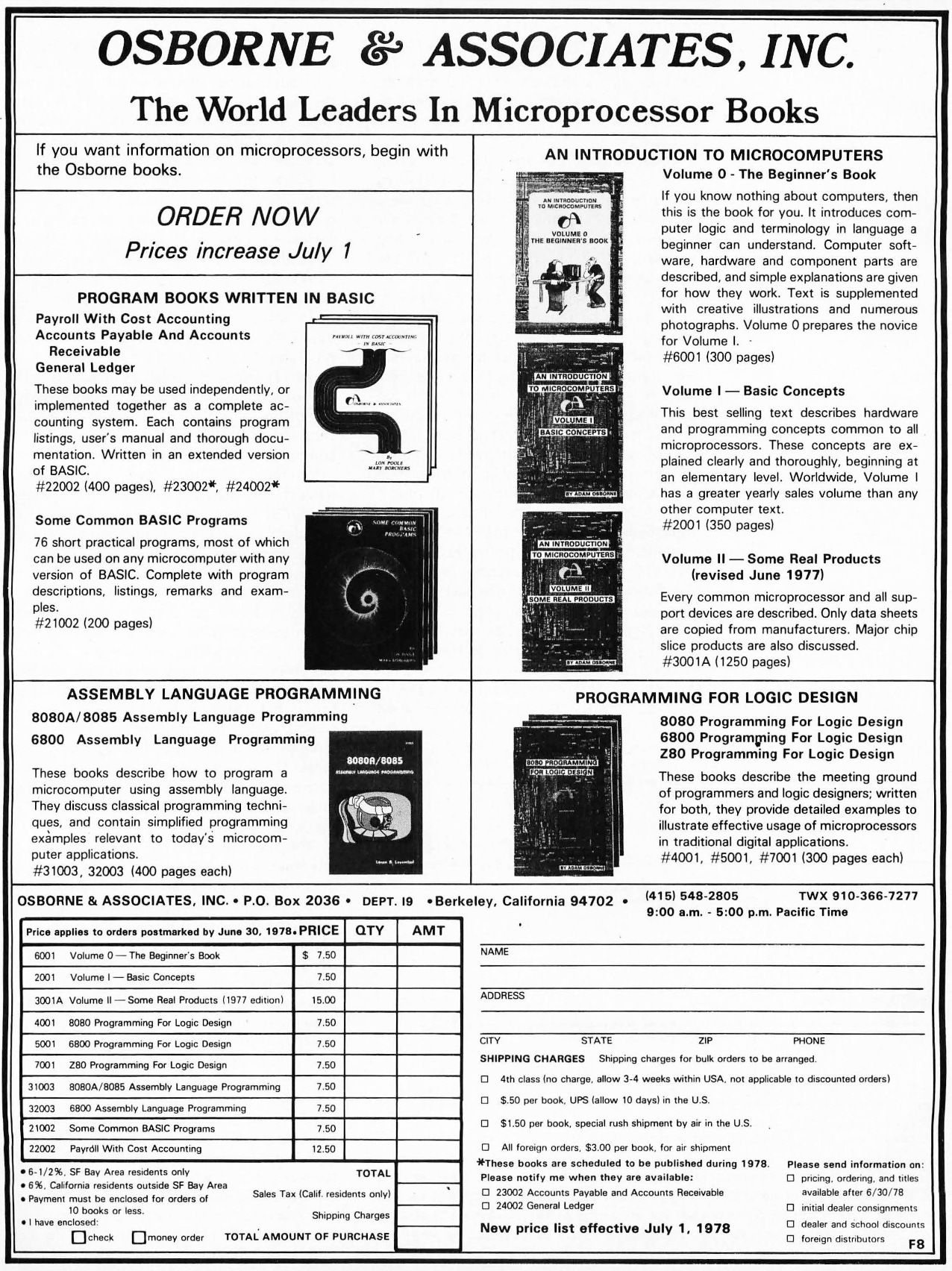

Being in California, particularly within driving distance of Menlo Park, Osborne began attending the Homebrew Computer Club. The first meeting was on the 5th of March in 1975 where a MITS Altair 8800 was present for review. After seeing the Altair, Osborne knew that a guide to using the machine was needed, and he wrote An Introduction to Microcomputers to fill that need. Despite the book having been well written and having filled a need, publishers at the time weren’t willing to publish it. The computer market was tiny and consisted almost entirely of enthusiasts. Osborne knew better. He started his own publishing company, Osborne & Associates Incorporated, in Berkeley, California. Not long after, Bruce Van Natta at IMS Associates (IMSAI) wanted a copy of The Value of Power and called up Osborne asking about it. Osborne informed him that he couldn’t get that book, but that he could get the new microcomputer book. IMSAI bought ten thousand copies at $4 each. One year after having seen the Altair, Osborne’s book had sold more than twenty thousand copies and thirteen schools were using it. His name and reputation quickly grew, and he began a column called “From the Fountainhead” in Interface Age.

In May of 1979, Osborne sold his publishing company to McGraw-Hill where it became Osborne/McGraw-Hill. Under the terms of this deal, Osborne was obligated to stay on until May of 1982, but he wasn’t required to be exclusively dedicated to the company. He could and did pursue other ventures. Brandywine Holdings was started in early 1980. The initial working space was shared with the “Community Memory Project” whose goal was to bring computing to the people via networked computer terminals in public locations. The CMP (founded by Lee Felsenstein, Efrem Lipkin, Ken Colstad, Jude Milhon, and Mark Szpakowski) was largely an electronics-enthusiast anarchist group. The anarchist part of that being quite normal for Berkeley, and the electronics part of that being the nerdy bit.

The hobbyist market had set a standard of the Z80 with CP/M, and two of the three major players, Apple and Commodore, had chosen to go their own ways. Despite that, the standard persisted with Tandy, North Star, Cromemco, Vector Graphic, and Morrow. In Osborne’s mind, both Apple and IBM had proven that one needn’t be the best to make sales, one only needed to supply something adequate that had good support and availability, or as he put it: “adequacy is sufficient; everything else is irrelevant.”

What was standing in the way? The wires. The average computer buyer at the time was expected to plug in multiple boxes, make sure everything was powered and properly configured, and then the buyer could use the machine. Osborne wanted to provide something as simple as a toaster; just plug it in and turn it on. To make this a reality, everything would need to be in a single box, and he wanted it in the smallest package possible. He then realized that this machine could be portable. He looked up the maximum size of a carry-on bag at PanAm, and those became the maximum dimensions of his computer.

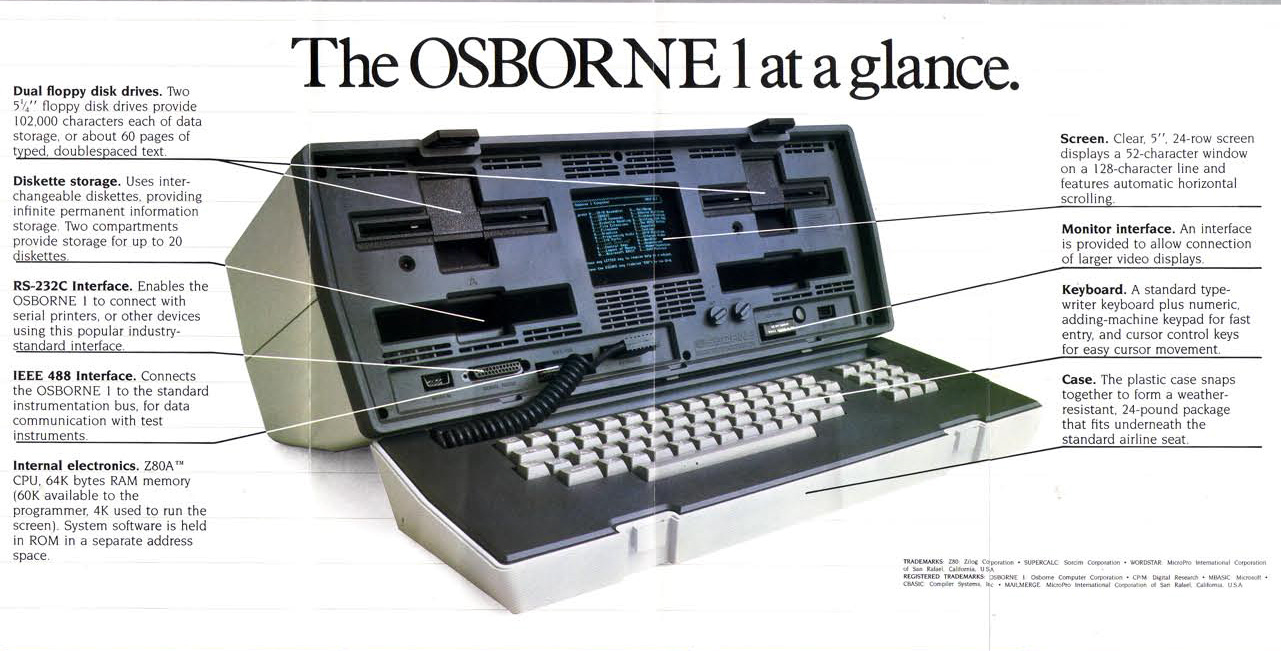

He now had his requirements: Z80 CPU, 64K RAM, CP/M, two floppy disk drives, keyboard, serial port, parallel port, and five inch screen. With those requirements established, he hired Lee Felsenstein whom he’d met at HCC, to design the machine in July of 1980. Osborne now had to go figure out the software. He purchased an unlimited CP/M license for $55,000. For BASIC, he traded 2875 shares of Brandywine stock for an unlimited license to CBASIC from Gordon Eubanks, and another 2875 shares for an unlimited license to MBASIC from Microsoft. The details of the WordStar license are unknown, but WordStar was included and we know that there were fees that were not per unit sold. VisiCalc was the standard in spreadsheets but VisiCorp wanted a million dollars for a port and license. Osborne didn’t like that much at all, so he contacted Richard Frank at Sorcim. He asked him to write a spreadsheet program with a few extra capabilities, and SuperCalc was born. This cost Brandywine around $20,000 and 4000 shares, and Sorcim retained the rights to sell the program to others if they paid back the development cost. All told, the software and documentation costs per machine would be a little less than $10 per computer.

By the end of 1980 with $100,000 from Osborne and $40,000 from Jack Melchor, a working prototype of the computer existed, the company had moved into a room loaned from Sorcim, and Tom Davidson had been brought in as VP and general manager as Osborne still had work at McGraw-Hill. Melchor, then insisted that the name of the company be changed to Osborne Computer Corporation to capitalize on Osborne’s name recognition, so in early 1981, Osborne Computer Corporation was officially born.

Through January and February of 1981, Osborne raised $900,000 ($3.2 million in 2025) from venture capital and acquaintances, and he assembled the initial board: Adam Osborne, Jack Melchor, Seymour Rubenstein, Les Hogen, Richard Frank, Robert Bily, Tony Bergis. Georgette Psaris came on as the VP of sales and marketing, Mike Iannamico handled documentation, and Annette Truesdell handled customer and dealer relationships. Frank didn’t get along with Felsenstein, and he claimed a conflict of interest as well. He resigned and Ken Oshman took his place in September.

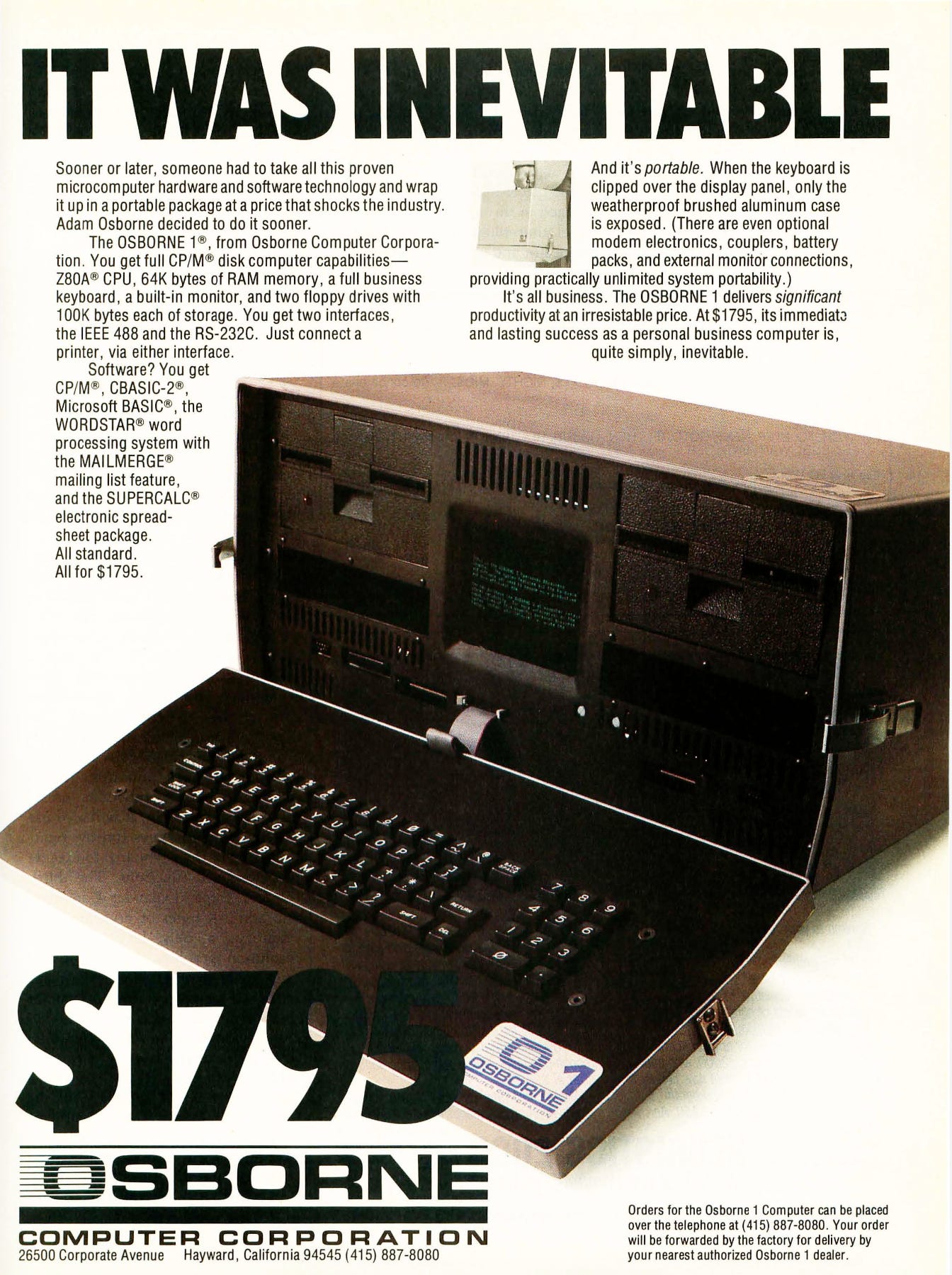

Pressure was on to have some machines ready for the West Coast Computer Faire held on the 3rd through 5th of April of 1981. Meanwhile, that one room office wasn't working for the quickly growing company. OCC moved into a bare building in Hayward, and people were working and making phone calls in between the construction interruptions going on around them. As the seemingly impossible deadline approached, the first machines were finished days before they were to be demonstrated. The final price for an Osborne 1 was $1795 which would be around $6587 in 2025 dollars. This price may seem high, but WordStar and VisiCalc weren’t exactly free. This price represented a rather high value per dollar. The final configuration of this machine was a 24.5 pound luggable (20.5 inches wide, 9 inches high, 13 inches deep) with a Zilog Z80 clocked 4MHz, 64K RAM, 5 inch monochrome CRT capable of 52 columns by 24 rows, parallel port, IEEE-488 modem port, serial port, dual 5.25 inch floppy disk drives, and software. That software included CP/M, SuperCalc, WordStar, MBASIC, and CBASIC. Optional accessories included an external 9 inch monitor, an acoustic coupler, upgraded floppy disk drives, and a battery pack which provided three to five hours of use.

The machine was heavy, it ran hot, and 16bit machines were right around the corner. Yet, this machine included two disk drives, 64K RAM, a monitor, expansion ports, and software. Were one to so configure a TRS-80, the price would have been higher at the time.

At the faire, we find that OCC was flamboyant. The company had a huge plexiglass booth that towered over others. Steve Jobs called and left a message: “tell Adam he’s an asshole,” at which Osborne laughed and used it as a bit of advertising. Initial impressions of the machine were mixed. People laughed at the screen size (typically until they used it for a bit), but they also generally liked the value. One thing was certain, people were talking about the machine.

The first Osborne 1 shipped on the 30th of June in 1981 to Gerald Wright of Digital Deli in Mountain View with serial number 000001. Jerry Pournelle reviewed the Osborne 1 a bit in the April 1982 edition of BYTE, and said of it:

In the middle of the dilemma, Adam Osborne sent me his new Osborne 1. That darned near solved my problem. Osborne’s machine is good. The first models had some faulty characteristics, but Adam is an honorable man and also smart enough not to risk his reputation by sharp practices. They’re planning retrofits to take care of all major difficulties and most minor ones. The worst of these was the shift lock, which was worse than useless. Then, too, with that tiny screen you needed smooth vertical scrolling (it already had good horizontal scrolling) . There have been some other minor annoyances, but as I said, Adam’s been fixing them. The new Osborne 1 computers - out by the time this is published - will incorporate the improvements, including true three-key rollover and a decent shift lock, and various other fixes. Those who have already bought the machines will be able to get them retrofitted absolutely free. One thing I thought would be a pain turned out not to be. That’s the tiny video screen. Adam has sent me his larger video monitor, which you can connect to the Osborne 1 with a cable, but I find I don’t use it. The little screen turns out to be just at the right focal distance when I sit at the console; and for someone like me, who wears bifocal glasses, that’s a real boon. I carried the Osborne lout to CalTech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratories for the Voyager 2 encounter with Saturn. There were over a hundred members of the science press corps packed into JPL’s Von Karman Center (the press facility) . Most had typewriters. One or two had big, cumbersome word processors. At least one was a terminal connected through a network to the parent system in New York. Nobody had anything near as convenient as the Osborne 1, which is quiet and fast responding.

He went on to describe responses from folks at JPL, and most said the screen was small. After using it, however, Pournelle stated that many were ready to go buy one for themselves. The one drawback that Pournelle saw was the disk format. It wasn’t compatible with the TRS-80. He did, however, note that OCC would be switching to the IBM format in later models.

If you’re wondering about the lag between the machine shipping and a solid review showing up in BYTE, this could easily be explained by OCC’s struggle in meeting demand. Production couldn’t keep up until around February of 1982, which coincidentally was about the same time that Mike Healey started selling Osborne 1s in the UK under the OCC subsidiary there. There were multiple business problems during that time as well. For example, Osborne was expanding into the UK, Germany, and Australia, and arranging that financing wasn’t always smooth.

Tom Davidson was apparently quite unhappy at the company. He went to Taiwan to do some manufacturing negotiation, and while there, gave an interview to some Italian journalists. He vented his frustrations but portrayed Osborne and OCC in a rather negative light. The result was that upon his return on the 24th of September in 1982, he was met at his office by a security guard, escorted to Osborne’s office, and promptly fired. Bob Jaunich was hired as his replacement and took the positions of president and CEO in January of 1983. For the first month, he was quiet and didn’t change much at all. After getting the lay of the land, he began changing things rapidly in February. Most of the prior management was fired and experienced industry professionals were brought on board.

For all this shake up, I am not certain how much of it was to the benefit of OCC. The company’s best quarter was that which ended in March of 1983 with the company having beat their projected sales every month.

Unlike most computer manufacturers of this era, OCC didn’t use distributors. The company manufactured their machines and then shipped directly to retailers. While this did decrease costs, it added a bit of logistics complexity for OCC. That doesn’t seem to have hurt them at all as by June of 1982, the company had nearly 3000 employees and had shipped a bit over 50,000 machines with sales hitting $70 million for the first year of the computer’s availability.

One place that the company struggled, seemingly from the start, was in their accounting systems. At one point in 1981, the system was offline and unable to process anything. This situation wasn’t quickly remedied, and Osborne himself was preparing the 1982 budget on an Osborne 1 in SuperCalc. The result of this is that the company didn’t really have much financial control in place, couldn’t forecast well, and thus, halfway through a project a team may be told they were over budget or out of funds rather unexpectedly. This also meant that spending on quality control couldn’t be allocated well which became a problem in early 1982, and it meant that the company’s overall sales figures weren’t as good as they’d planned and budgeted. So, in the quarter ending on the 29th of May in 1982, the company lost $1.3 million on revenues of $10 million. That month, Adam Osborne was finally able to work at the company full time. The company turned things around with August revenues exceeding $21 million. The issue is, cost of sales were high at $15 million, and after other expenses, the company’s profit was just $290,000. In November, revenue was nearly $30 million and profit was just $298,000.

The Osborne Executive (or OCC-2) was shown to the press in early 1983 with a ban on press until April. The machine was officially announced on the 18th of April in 1983 at a price of $2495. It was bundled with CP/M Plus, MBASIC, CBASIC, WordStar, SuperCalc, Personal Pearl database, and UCSD p-System. The hardware in this machine was upgraded over the OCC-1 with the machine having 124K RAM, a beeper, and a 7 inch amber display capable of 80 columns by 24 rows. The machine was heavier at 28 pounds, and the optional external battery could provide only an hour of run time. The machine now required a fan and air filter, and the case was more square. The handle was also a bit smaller than the original.

This computer had some special tricks. For example, it could run some synchronous communications software that emulated an IBM 3271 terminal for use with IBM mainframes. Other terminal emulation was promised (more IBM models and other terminals), but I do not know if it was ever available. Part of what enabled this was the OCC-2 having fifteen different baud rates. At power up, the OCC-2 would first run a self-test, and it could then be configured with the aforementioned baud rates, multiple cursor options, display reversal, keyboard click, 50Hz or 60Hz power, and character sets.

At this point, the company had about 15,000 OCC-1s on hand and ready to be shipped to retailers. The combined discontinuation of bundling Ashton-Tate’s dBase-II and the announcement of the Executive ahead of availability meant that quite a few retailers cancelled their orders for OCC-1s and ordered Executives instead. This was especially bad as word had made it to retailers ahead of announcement. OCC couldn’t fulfill their orders and this isn’t a good situation for a company that had small profits. Adding fuel to this fire was continued competition from Kaypro, and new competition from Compaq and around 50 other companies making portables. Computers could now be had for between $1000 and $3000 from nearly 300 distinct companies which took away OCC’s price advantage. Roughly half of the company’s international workforce were laid off in early May, and 92 staff members in Hayward were laid off on the 13th of May. Another 93 staff at Hayward were laid off on the 16th of June. On the 2nd of August, another 202 people lost their jobs, their manufacturing plant in Monmouth Junction, New Jersey was closed the following day with about 90 workers there now unemployed, followed by 312 more in Hayward on the 9th of September. The company filed for bankruptcy on the 15th of September in 1983. The company’s poor accounting practices then led to law suits from 24 investors on the 22nd of September. The company had around 80 employees, around $40 million in liabilities, and around 600 creditors. I’ve read some reports of Osborne computers being sold at auctions around this time for as little as $300 per unit.

Ronald J. Brown took over as CEO submitted a plan for exiting bankruptcy to California on the 13th of December in 1983 which was approved in the first quarter of 1984. By this point, OCC was constituted by just thirty full-time employees. Existing stocks of both the OCC-1 and OCC-2 were being sold while the company worked to produce new machines. With less staff, these were sold to users’ groups who began to serve as independent buyers just as distributors and dealers would have for other companies. Osborne was open to working with dealers and other companies, but they were starting from a bad position. Interestingly, rather than offering support themselves, OCC sold one-year service contracts from Xerox.

In 1983, at the West Coast Computer Faire, long before the products would have been available, Osborne had stated to attendees that both a PC-compatible upgrade board for the Executive and a PC-compatible Executive II would be available in half a year or so. Seemingly doubling down on the mistakes made with Executive itself earlier that year. Still, the IBM PC had set the standard and played a large role in the failure of the Osborne Computer Corporation. The company worked to create the Osborne PC, and it was announced in 1984 at the West Coast Computer Faire. The machine resembled earlier OCC machines but was blue, weighed 28 pounds, featured an Intel 8088 CPU at 4.77MHz, packed 256K RAM standard, two 5.25 inch floppy disk drives, two serial ports, a parallel port, a seven inch monochrome amber screen, and RGB out. It could be upgraded with an additional 512K RAM and an 8087. As cool as the Executive II or Osborne PC might have been, it was never released.

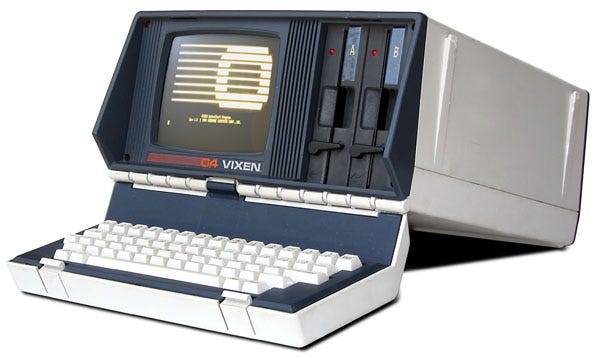

The last two Osbornes to be released were the Osborne Encore (OCC-3) and the Osborne Vixen (OCC-4). The Encore was essentially a Morrow Pivot (designed and manufactured by Vadem) with the good and the bad that that implied. It used an 8088, 256K RAM, 16K ROM, a ten inch monochrome LCD (no backlight) capable of 80 columns by 16 lines or 480 by 128 pixels. The Encore was an IBM-compatible, but not fully so; without a backlight the screen could be hard to read in rather normal lighting conditions, and the 16 line display made quite a bit of software nearly unusable. The Vixen was far more recognizably an Osborne with a 4MHz Z80, 64K RAM, 4K EPROM, seven inch amber monochrome display capable of 80 by 24, two disk drives, and weighed in at 18 pounds. It packed CP/M 2.2, WordStar, SuperCalc 2, MBASIC, the Osboard graphics/drawing program, Media Master data interchange program, TurnKey automated setup application, and Desolation (game). The Vixen was priced at $1298 without an HDD. An external 10MB hard disk increased the price to $1495 and with an internal hard disk to $2798. These machines were available in 1985. The OCC-3 wasn’t much of a match from something like the Compaq Portable, and the Vixen was an 8bit CP/M machine in the time of 16bit DOS machines. They failed to bring OCC back.

By 1986, the company’s creditors were attempting to find more money, but all efforts in this arena failed. On the 31st of January in 1986, Jerome E. Robertson was appointed as the Osborne Computer Corporation’s liquidation trustee and he oversaw the sale of the company’s inventory and assets. OCC’s creditors committee asked the bankruptcy court to declare OCC in default on the 5th of February in 1986. A few of the international offices of OCC did continue to operate, but these branches largely sold rebadged IBM compatible machines. Osborne Australia did particularly well until filing for bankruptcy on the 25th of June in 1995. What was left of the company was then sold to Gateway.

Quite a bit has been written about the Osborne Effect. The idea being that the primary reason for OCC’s failure was the premature announcement of future products. It is true that OCC would have sold more OCC-1s had Adam Osborne not revealed multiple future products that were better than the OCC-1 in every conceivable way. This may have prolonged the company a bit, but it wouldn’t have been sufficient. The company had poor bookkeeping practices, an incredibly high CAC, and the company’s timing was brutally bad, releasing an 8bit CP/M machine as the world was transitioning to the new IBM PC compatible standard. OCC’s importance to the industry is not found in the company itself but rather in pioneering the commercial portables market, the bundled software market, and the “spectacle” of releases tradition with their flashy booths at WCCF. Thank you to all of the folks who worked at Osborne Computer Corporation for your contributions to this industry.

My dear readers, many of you worked at, ran, or even founded the companies I cover here on ARF, and some of you were present at those companies for the time periods I cover. A few of you have been mentioned by name. All corrections to the record are sincerely welcome, and I would love any additional insights, corrections, or feedback. Please feel free to leave a comment.