The Story of Creative Technology

The Sound Blaster

Sim Wong Hoo was born on the 28th of April in 1955, the tenth child in a family of twelve children (five brothers, seven sisters). His family were Singaporean Hoklo with ancestry in the southernmost area of Fujian, China, and they spoke Hokkien. He grew up in a kampung called End of Coconut Hill in Bukit Panjang, and his father, Sim Chye Thiam, was a factory worker while his mother, Tan Siok Kee, raised chickens, ducks, pigs, and rabbits, and grew fruits and herbs. The young Sim had chores around the house and around the farm as soon as he was physically able, and he often sold eggs at the local market before school classes started each day. This afforded him the ability to buy things for himself such as his harmonica when he was about 11. The harmonica was a hobby he greatly enjoyed throughout his life. He also enjoyed making his own games.

Sim graduated from Bukit Panjang Government High School and then went on to attend Ngee Ann Technical College for engineering. At the college, Sim was a member of both the harmonica troupe, consisting of thirty people, and the Practice Theatre School. In the theatre, Sim provided musical accompaniment for the school’s performances with the harmonica and the accordion, often performing his own arrangements. His two interests collided at this time in his life. When writing or arranging music, he’d only be able to hear his composition during weekly practice. Having seen a computer, he realized that a computer could allow him to hear the music precisely as written while still working on it. Sim envisioned a computer that could play music, talk, or even sing, and his earlier entrepreneurial spirit drove him to an ambitious goal: selling 100 million units of a single piece of equipment. Sim graduated in 1975 and then entered the uniformed services for his obligatory two years.

For three to four years following his service, Sim worked a brief stint on an offshore oil rig, designing computerized seismic data logging equipment. After that, he opened a computer education center at Coronation Plaza. As he was more interested in teaching and researching, he left the business work to his business partner. This wasn’t a great decision. His partner took off with all the money.

On the 1st of July in 1981, Sim founded Creative Technology with Ng Kai Wa, who had been his childhood friend and classmate in a 440 sqft shop at Pearls Center using his own savings of around $6000. The company initially did computer repair and sold parts and accessories for microcomputers. Business wasn’t great, so Sim also did some teaching. In whatever time he had left to him, he was busy developing his own products.

The first Creative product (at least, for which I can find any evidence at all) was a memory board for the Apple II. Having an understanding of the Apple II, Creative followed their memory board by producing the CUBIC 99 in 1984. This was an Apple II compatible machine with a 6502, but it also featured a Zilog Z80 for compatibility with CP/M. I am not certain how this was arranged, but I imagine that it wasn’t entirely dissimilar to the Microsoft Z80 SoftCard. Of course, this is Creative Technology, so the machine also featured a voice synthesizer allowing users to record and playback words in English or Chinese. The computer also had an optional Cubic Phone Sitter which could make and answer calls. This was the first computer to be designed and manufactured in Singapore.

The market was moving quickly, and the IBM PC had created a standard. The CUBIC CT was released in 1986 as a PC compatible, and it featured graphics and sound capabilities. This was, essentially, a multimedia PC (with a weaker CPU than that standard would later dictate) localized in the Chinese language. Unfortunately, it was too early. With nearly zero software support for anything approaching the capabilities of the CT and an even smaller local market, the product was a failure.

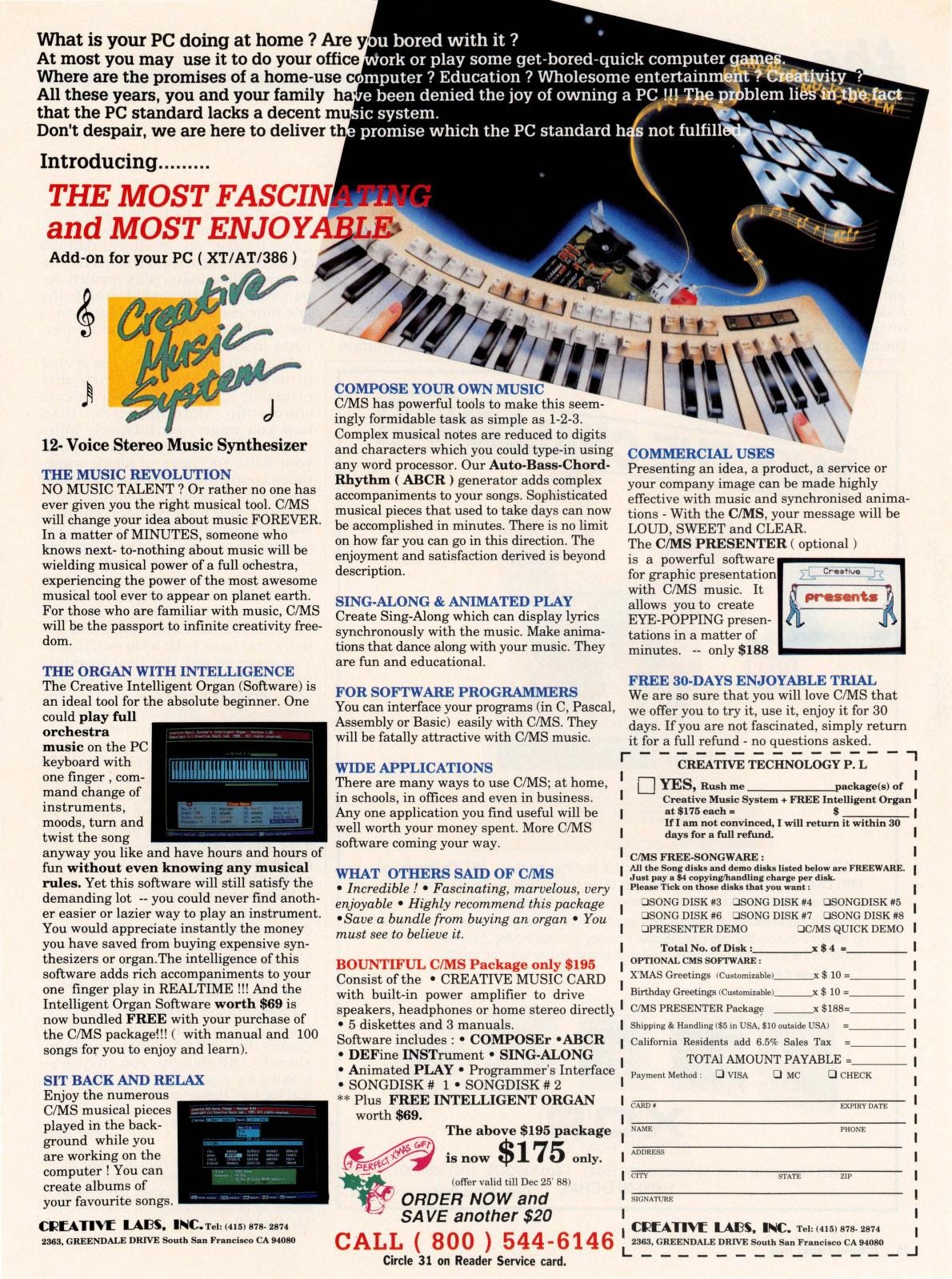

Realizing that the sound features of the CUBIC CT were likely more salable and supportable than the computer itself, Sim and his company chose to sell the sound card by itself as the Creative Music System (also C/MS or CT-1300). This board was built around two Philips SAA1099 chips providing 12 channels of square-wave stereo sound on a half-length 8bit ISA card, and it shipped with five 360K 5.25 inch floppy disks (Master Disk, Intelligent Organ, Sound Disk 1, Sound Disk 2, Utilities). To promote this card, Sim moved to California in 1988 and established Creative Labs. His goal was to sell at least 20,000 cards generating $1 million in revenue. The USA was the largest PC market, and he knew that sound cards were seeing good sales.

Being in the USA, Sim quickly realized that games were the software titles driving sound card sales, and this meant that he’d need new branding and software partners. The C/MS became the Game Blaster, and the included software was now just the Intelligent Organ, a test utility, a TSR, and drivers for Sierra Online games. The inclusion of those drivers was key to what would follow. Creative’s partnership with Sierra meant that some of the most popular games of the era would support the Game Blaster; ultimately, over 100 games would support the C/MS and Game Blaster. Naturally, selling a card required a store front, and Creative found a partner in Radio Shack. While the Game Blaster sold better than any Creative product before it, it didn’t overtake the Adlib.

To better compete, Creative needing something that was better than the Adlib but still compatible with it. This came in 1989 with the CT1310, better known as the Sound Blaster. The Sound Blaster offered 12-voice C/MS stereo sound, 11-voice FM synthesis with Adlib compatibility (via the Yamaha YM3812), a MIDI interface, a joystick port, microphone jack with a built-in amplifier, a stereo amplifier with volume dial, the ability to play back mono-sampled sound at up to 22kHz, and record at 12kHz. While a sample rate of 22k doesn’t seem great (because it isn’t) this did allow simultaneous output of sound effects and music in a game. Likewise, while a game port doesn’t seem like all too big a deal, it saved the buyer an extra $50 to buy one separately, and it saved an ISA slot too. The Sound Blaster was the first sound card to feature digital sample playback, and it took over the market, quickly becoming the top-selling expansion card of any kind in under a year, and Creative’s revenues hit $5.5 million. With the C/MS never having been too popular, Creative followed the CT1310 with the CT1320 which removed the C/MS chips but kept sockets for them on the card.

1989 also saw Creative release the PJS operating system and the PJ Views word processor and desktop publishing system which included support for 70,000 Chinese characters. As far as I know, these products were only released in Southeast Asia.

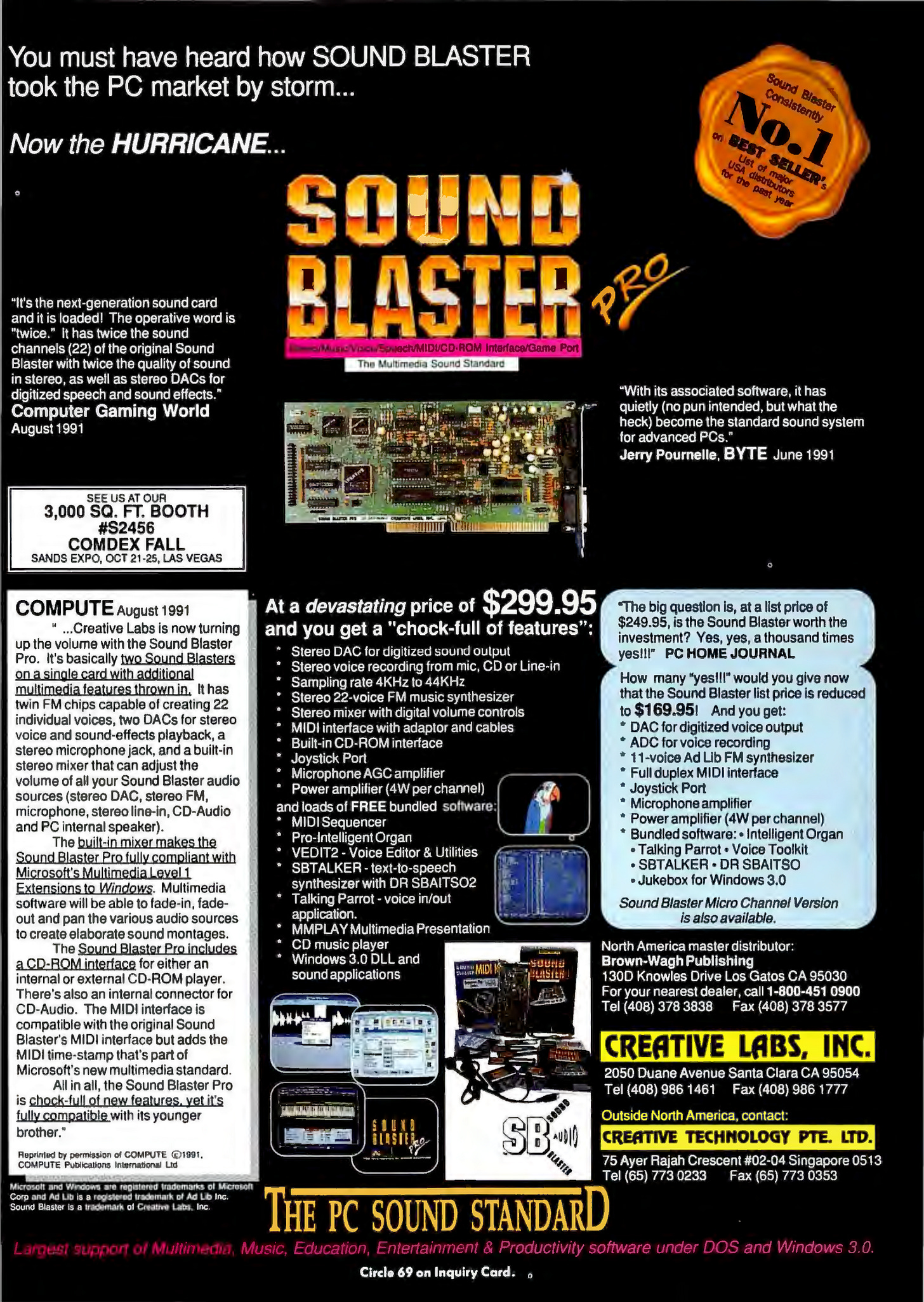

Announced in May of 1991, the Sound Blaster Pro, CT1330, was a major redesign of Creative’s sound card. This card used two Yamaha YM3812 chips to provide stereo sound while maintaining full backward compatibility with the original Sound Blaster and Adlib. Sample rates were increased to 22kHz for stereo, 44.1kHz for mono. A simple mixer, low-pass filter, high-pass filter, and CD-ROM interface were added. This CD-ROM interface could take multiple forms, but it was useful in pushing CD-ROMs into the mainstream. Many early CD-ROM drives were SCSI-only and that was expensive. Creative worked with MKE in Japan to produce low-cost IDE CD-ROM drives, and then included support on their cards. As for the card itself, while the card did have the AT connector, it wasn’t 16bit. The Pro was still an 8bit card. The presence of the 16bit AT connector was for additional interrupts and DMAs on the 16bit bus that supported the Multimedia PC standard from Microsoft. The Sound Blaster Pro 2 was released shortly after the original, and it replaced the YM3812s with a single YMF262. The Pro series was often sold in Multimedia Upgrade Kits where it was bundled with a CD-ROM drive and software titles. Given that CD-ROMs were quite new, these kits often represented a significant value to consumers.

This card can also be found in Tandy Multimedia PCs as the Tandy Multimedia Audio Adapter. Immediately noticeable changes were from the regular joystick port to two mini-DIN connectors compatible with the Tandy 1000 joysticks, and the addition of a mini-DIN MIDI port. For both the joystick connectors and MIDI connector, adapters were required. A less noticeable change, the Tandy card used a different bus interface chip, the CT1346, and the output amplifier could be disabled via a jumper. Finally, the card featured a high-DMA channel allocated for audio which allowed 16bit 44.1kHz mono output in Windows.

The Sound Blaster 2, or Sound Blaster Deluxe, model CT1350 was released in October of 1991. This model improved the board layout allowing for a more compact card, and it completely eliminated the C/MS chips. This model improved on its predecessor by adding auto-init to DMA allowing the card to play continuously without the crackling or pausing that was experienced on the original. The sample rate for digital audio on this card was increased to 44kHz for playback and to 15kHz for recording. With this card, a DSP upgrade was made available to owners of the original Sound Blaster, which was required for full compatibility with the Windows 3 multimedia extensions.

Creative was growing quickly, achieving an estimated 72% market share of the sound card market globally in 1992, but it was also facing significant competition. Media Vision’s Pro Audio Spectrum Plus, released in 1991, was capable of 8bit digital sampling and 16bit digital audio playback. It featured a CD-ROM interface, and it was Sound Blaster compatible. The Pro Audio Spectrum 16 of 1992 moved the company to 16bit ISA, added 16bit stereo digital audio, and featured stereo FM synthesis while maintaining full Sound Blaster compatibility. Then, there was Aztech in the more low-end market making some serious OEM deals with likes of Dell and Compaq. They entered the market in 1992 at a much lower price point and offered broad compatibility with sound cards like the Adlib, Sound Blaster 2, Sound Blaster Pro, Cover Speech Thing, Disney Sound Source, and Windows Sound System.

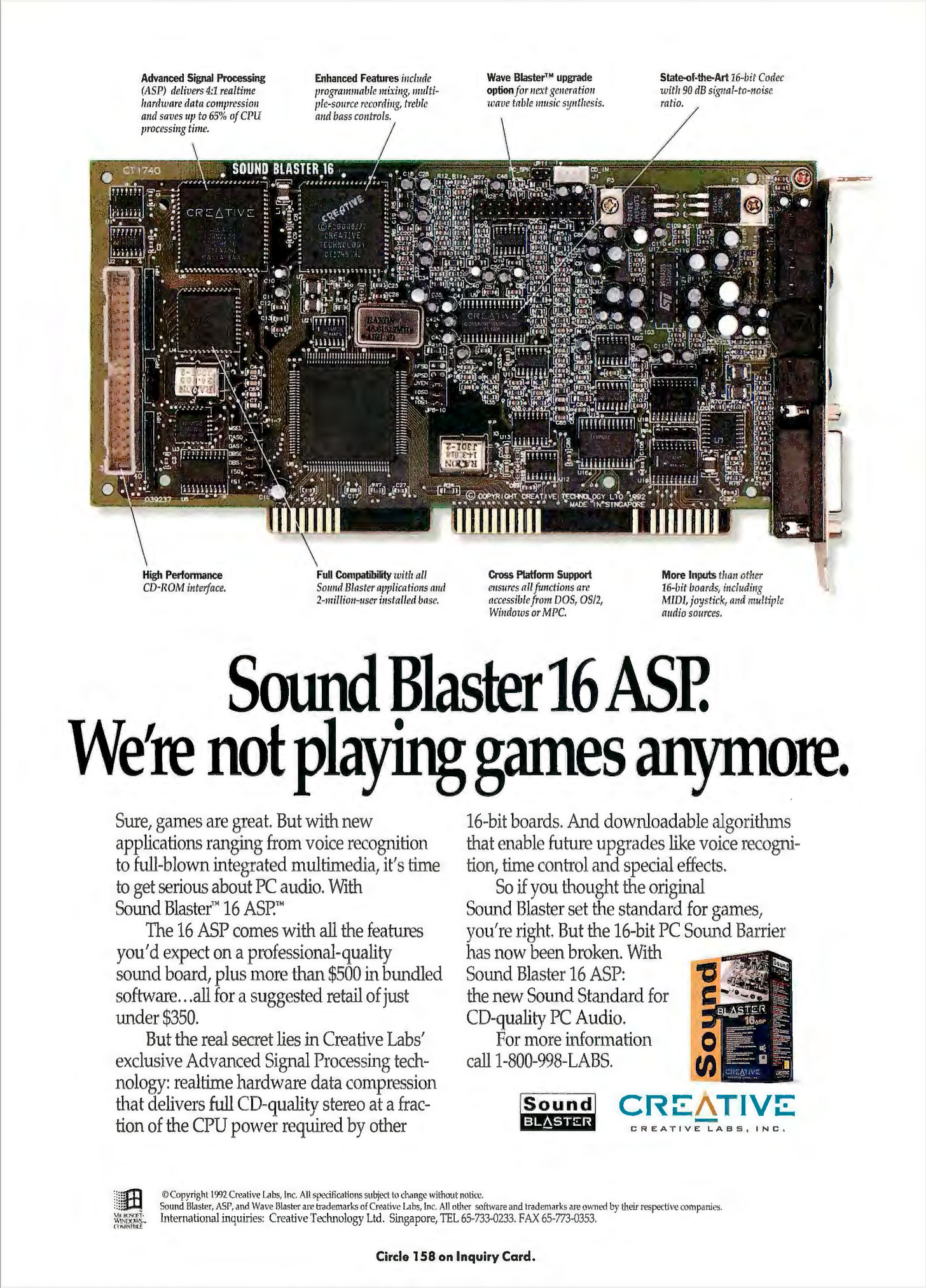

To answer the competition and maintain their lead, the company released the Sound Blaster 16, CT1740, in June of 1992. This was a fully 16bit sound card and featured support for 16bit 44.1kHz digital audio. Creative had partnered with E-mu Systems to offer the Wave Blaster daughter board that brought wavetable synthesis to card through the header on the top of the card. The empty socket seen on the SB16 was for the Creative Signal Processor, CT1748, which brought hardware-assisted speech synthesis, QSound audio spatialization for digital wave playback, and PCM audio compression/decompression. The SB16 was more popular than any card before it, and the wavetable daughter board was popular enough to push Creative to acquire E-mu in March of 1993 for $54 million.

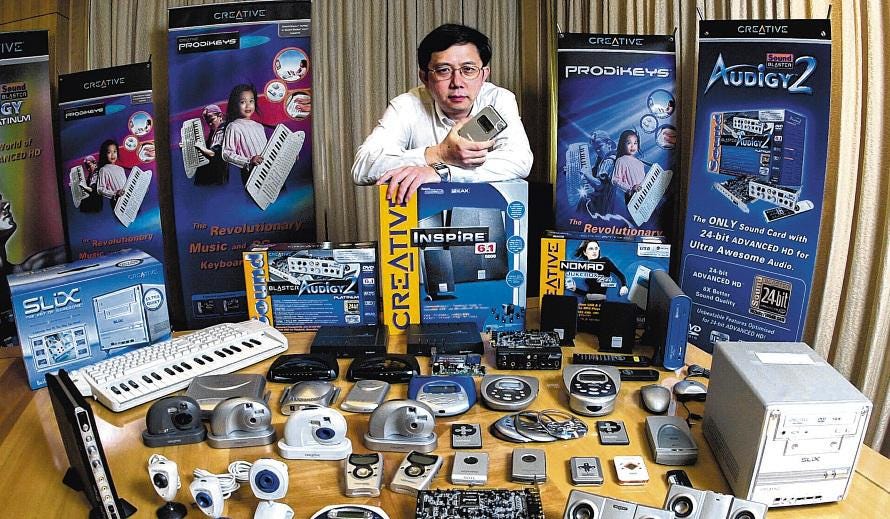

Creative went public in August of 1992 and became the first Singaporean company to be listed on the NASDAQ. In September of 1992, Creative expanded into China establishing a joint venture in Beijing called Chuang Tong Multimedia Computer Ltd. Creative held 70%, NewStone 20%, and Da Heng 10%. In addition to selling the company’s multimedia hardware, the Chinese subsidiary developed and distributed CD-ROM software in the Chinese language, and sold PJS and PJ Views. The following year, Ed Esber, formerly of Ashton-Tate, joined Creative Labs as CEO, and he assembled a team that included Rich Buchanan, Gail Pomerantz, and Rich Sorkin. Of the new team in the USA, Sorkin had the most lasting impact. He began licensing programs, shortened product development cycles, and began legal endeavors to protect Creative’s intellectual property. Throughout 1993, Creative established itself Australia, Japan, the UK, and Ireland. Finally, that same year, Creative acquired ShareVision Technology who made videoconferencing technologies. Creative’s later attempts in that market didn’t make it far.

By 1994, the Sound Blaster 16 was the audio card. The company needed both a low-end product and high-end product, and so the ViBRA 16, CT2501, took the low, and the AWE32 took the high. The ViBRA was a cost-reduced, single-chip implementation of the SB16 and was frequently supplied to OEMs. Some ViBRA models included an on-board modem. The AWE32 featured the CT1748 CSP, CT1747A with OPL3 FM synth, CT1971 (EMU8000) and CT1972 (EM8011, 1MB sample ROM) wavetable synth, CT1745A mixer, CT1741 DSP, a CD-ROM interface, wavetable header, SPDIF header, and 512K of sample RAM upgradeable to 28MB via two 30-pin SIMM slots. The AWE32, CT3900, was a full-length, 16bit, ISA card. With the SB16, ViBRA, and AWE32 on the market, the company’s revenues exceeded $650 million, and the company was listed on the Singapore stock exchange.

On the 26th of October in 1994, in time for the Christmas shopping season, Creative released the 3DO Blaster. This brought 3DO games to the PC via a full-length, 16bit, ISA card. On the card was a 32bit RISC CPU, a DSP for CD audio, two graphics processors, 2MB of RAM, 1MB of ROM, 1MB of VRAM, and 32K SRAM with battery backup. The box contained two games (Shockwave, Gridders), some demos, drivers, Aldus Photostyler and Gallery Effects, a controller, manuals, the card itself, and a registration card. Of course, the 3DO blaster was not, itself, a standard VGA card. To use the 3DO Blaster, one’s PC would need to be at least a 25MHz Intel 386, have at least 4MB of RAM, a VGA card, Windows 3.1, a CD-ROM drive (either Matsushita or Creative CR-564), a Sound Blaster, and some speakers. The press release from 3DO read, in part:

With the introduction of 3DO Blaster, Creative is targeting their extensive installed base of CD-ROM users. 3DO Blaster provides PC owners with the ultimate game platform — exciting 3DO games recognized for unprecedented interactive realism, full-motion video, CD-quality audio and three-dimensional sound effects.

“Today’s announcement reflects the efforts of two of the most advanced technology suppliers, Creative Technology and 3DO. The 3DO Blaster provides the advantage of Creative’s and 3DO’s innovation to the installed base of PC’s already using Creative multimedia products,” said Sim Wong Hoo, CEO and chairman of Creative Technology Ltd.

“Creative’s and 3DO’s technologies create an advanced entertainment platform which will enhance the capabilities of PCs, and expand the imagination of users by providing them access to exciting, interactive products that fully exploit the potential of multimedia entertainment.”

Trip Hawkins, president and CEO of The 3DO Company, said today’s announcement enables his company to expand quickly and aggressively into the vast PC market. “Creative is the leading supplier of multimedia products for PCs, providing us with the opportunity to deliver 3DO’s advanced interactive technology to an even broader audience,” said Hawkins.

Given that the 3DO Blaster cost $399.95 and the 3DO console didn’t do too well, this product was moribund from the start.

Also in October of 1994, Creative released HansVision. This was a Chinese-language office suite for Windows, and while Windows replaced PJS, HansVision replaced PJ Views. Also in 1994, Creative acquired Digicom Systems, a modem company. This resulted in the Creative Phone Blaster in 1995. The Phone Blaster, CT3110, was largely just a ViBRA 16 with an integrated modem and a wavetable header, but it was a full-length, 16bit, ISA card. It faired better than the company’s attempts at video conferencing, but it wasn’t much of a success.

A cost reduced version of the AWE32 was released in 1995 as the Sound Blaster 32. It was roughly equivalent to the AWE32 but lacked the on-board RAM, Wave Blaster Support, and CSP. Additionally, it utilized the CQM chip from the ViBRA instead of the OPL3. The CQM (Creative Quadratic Modulation) commonly suffered audio clipping, hiss, and ringing when playing digital audio.

Esber, Buchanan, and Pomerantz left the company in 1995. They’d never really got on with the folks in Singapore, and the two groups had disagreements over the company’s strategy. Sorkin, however, was promoted to General Manager of the audio division, and then to executive VP of business development and corporate investments.

With the earlier success of the company’s CD-ROM and sound card bundles packing Matsushita, Mitsumi, and other vendors’ drives, Creative had gone into the CD-ROM drive business. In 1995, the industry had a large oversupply and Creative dumped its inventory incurring a loss of $30 million, and causing the company’s share price to drop nearly 75%.

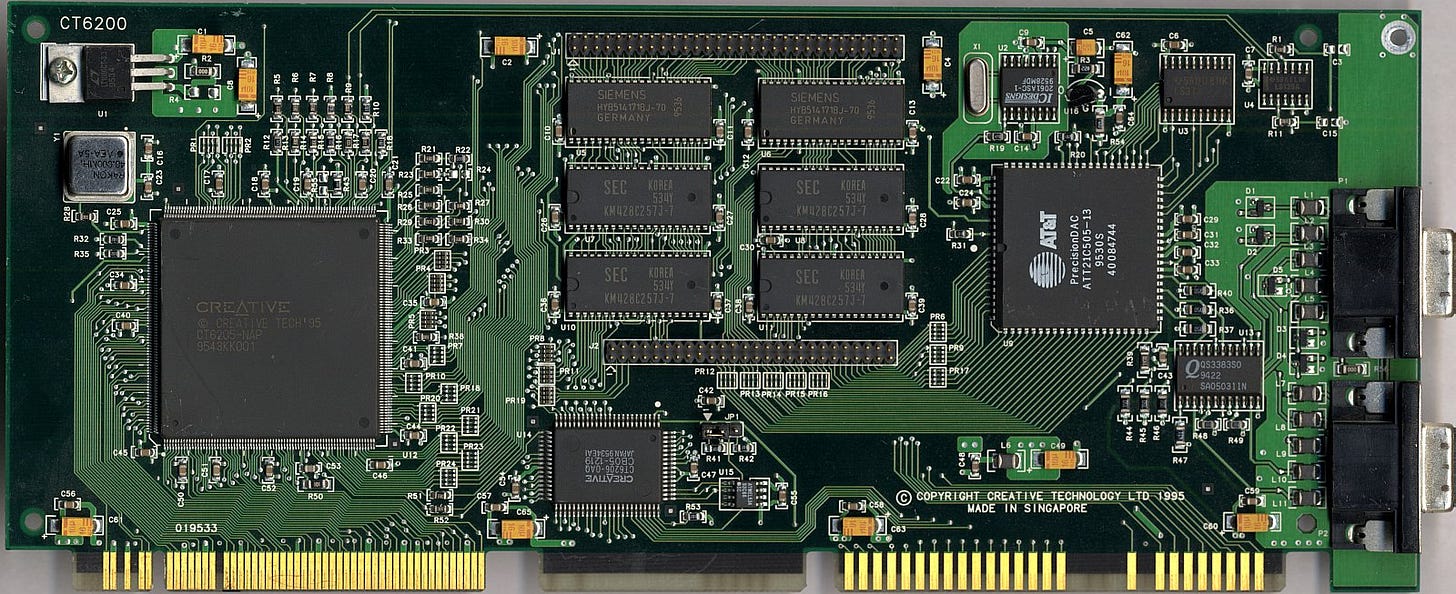

In 1995, Creative released the 3D Blaster, CT6200. This was a 3D accelerator card built around the 3DLabs GLINT 300SX processor. The GLINT 300SX was built of about a million transistors on IBM’s 3.3V, 0.5 micron process, and it was capable of about 2.5 billion operations per second. As with many cards that would follow, GLINT was designed to process Gouraud-shaded, Z-buffered, dithered triangles that were generated by an application or game and passed to GLINT via the OpenGL API (in this case CGL, and later DirectX). The chip was accompanied by 2MB (or 4MB with the 2MB daughter board) of DRAM, and this VESA Local Bus card achieved a pixel filtrate of 25MP/s. The card cost $349.95 at launch and it only handled 3D, requiring the user to have a 2D card installed and use VGA passthrough. This was roughly a year before the first Voodoo card, but shortly after the Diamond Edge 3D with an NV1 at $299 for 2MB. Given that this was a VLB card, the 3D Blaster was largely a card for 486 machines, and given the price, it didn’t sell well. As far as I am aware, there were roughly 13 game titles to support CGL. Of those, there was Rebel Moon which was exclusive to the CT6200, and even having been designed exclusively for this card, it wasn’t great. Frame rates would get quite sluggish at times, likely having been hampered by the 486 at the heart of VLB machines.

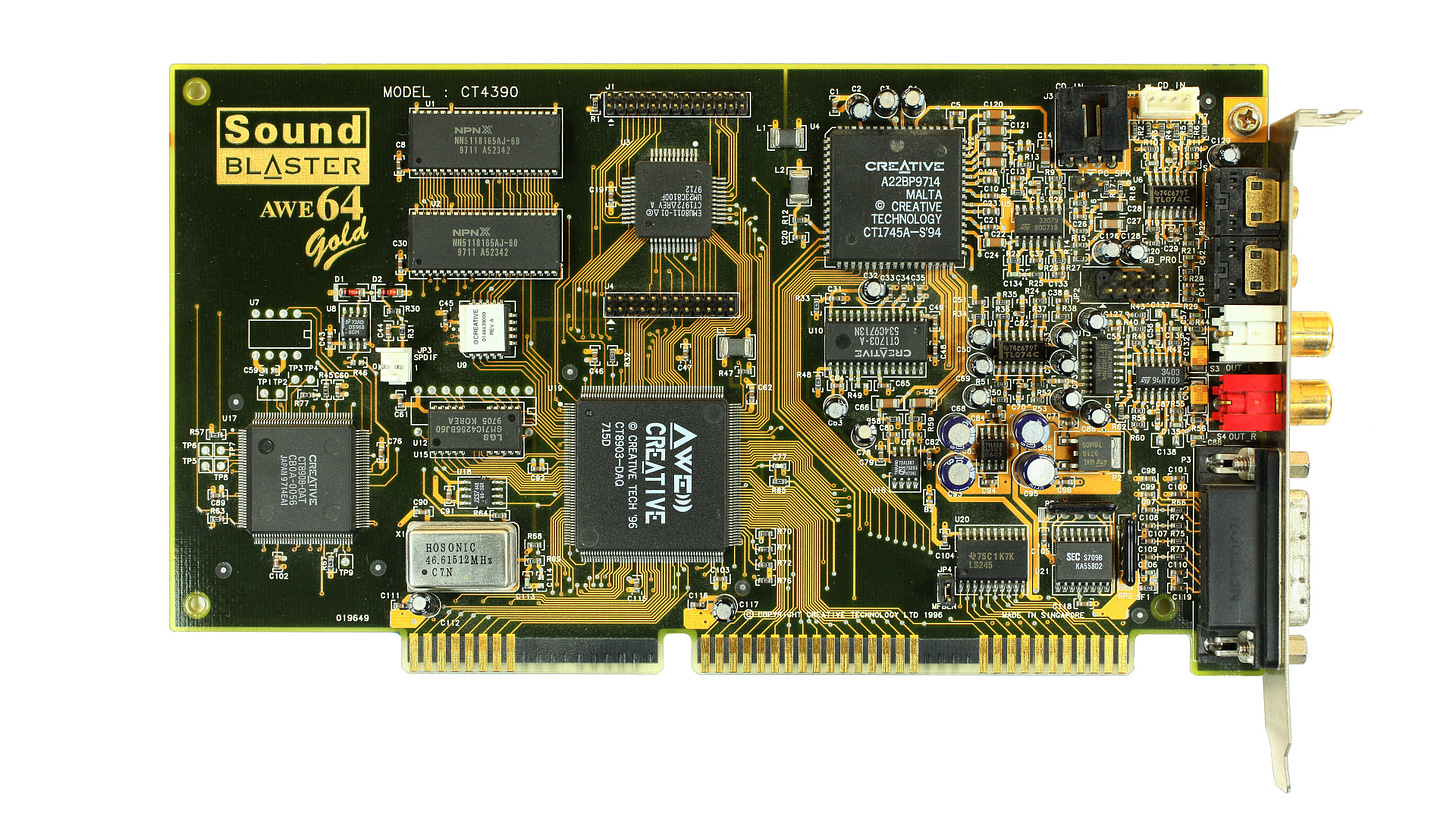

The Sound Blaster AWE64 was released in November of 1996, and it improved on the AWE32 in a few ways. First, it increased the signal to noise ratio (especially in the Gold version), and increased component integration resulting in traces that likewise avoided noise. Given increases in integration, the board also became smaller than its predecessor and decreased cost. It’s also notable that with general technological advancements made in the industry, the ICs were of a consistently higher quality than those used in earlier cards despite being less expensive. The card came in two versions; one was the standard version which later was re-branded as the Value version (CT4500) with 512K RAM, and the other was the Gold version (CT4390) with 4MB of RAM, a 20bit DAC, and separate SPDIF output. Functionally, there were two major differences between the AWE64 and AWE32. The AWE64 added WaveGuide which synthesizes instrument sounds. While the Wave Blaster is no longer supported, the AWE64 Gold does have line inputs on the rear for an external Sound Canvas or similar product. Effectively, the WaveGuide feature allowed for greater polyphony through the use of 32 extra software-emulated channels, but in practice this used more CPU time and wasn’t very popular. The other change was the removal of 30-pin SIMM slots in favor of proprietary memory daughter boards. In all other respects, the AWE64 was simply a better AWE32. For purists, the AWE64 lacks Sound Blaster Pro compatibility and genuine OPL3 FM Synthesis, but for those who want SB16 compatibility, mostly noise-free output, hassle-free plug-n-play, and General MIDI capabilities, the AWE64 is wonderful. For collectors today, however, owning a genuine AWE64 Gold will set a buyer back between $200 and $400. That price will increase for those desiring a SIMMConn (replacing the proprietary memory daughter board with a 30-pin SIMM adapter).

Creative closed 1996 with $1.6 billion in revenues, and Sorkin left the company for Elon Musk’s Zip2.

Media Vision will get its own article at some point, but the company collapsed in a scandal, and Aureal Semiconductor was formed on the 9th of November in 1995 out of the prior company’s remnants. On the 14th of July in 1997, Aureal announced the Vortex AU8820 with high quality positional audio via the company’s A3D technology. This allowed a human listener to perceive audio as coming from a rather precise location, and it had originally been developed by Crystal River Engineering for NASA’s Virtual Environment Workstation Project. Crystal River had been acquired by Aureal in May of 1996, and Aureal productized the technology. The Vortex proved to be extremely popular and its features were supported by many of the most popular gaming titles of the time: Half-Life, Unreal, Quake II, and so on.

For Creative, the arrival of the Vortex card was existential. Most of the company’s revenues came from sound cards, and the Vortex had gained the respect of gamers and audiophiles almost immediately following its release. What was worse was that its feature set was being incorporated into games where once the Sound Blaster had been the de facto standard. The fastest way to gain expertise is to buy it, and Creative bought Ensoniq in January of 1998 for $77 million. Within Creative, Ensoniq was merged with E-mu Systems. The acquisition brought the Ensoniq AudioPCI into Creative, and this was a card intended to be cheap, functional, and feature rich. It supported digital effects such as reverb, chorus, and spatial enhancement, as well as DirectSound3D, and sample-based synthesis. For the new owner, the card couldn’t have been better as it support Sound Blaster compatibility through the use of a TSR despite being a PCI card. This card was rebranded several times as the Sound Blaster PCI 64, PCI 128, Vibra PCI and so on. The Ensoniq ES1370 that powered the card became the Creative 5507, and then revised into further AC97 variants. A major downside of the card was that it ran with a 44kHz sample rate only, and thus, audio recorded at any other rate was resampled which lowered fidelity and increased CPU time. The later AC97 variants supported only 48kHz natively, and therefore likewise resampled audio. While the AudioPCI wouldn’t win over audiophiles, its low cost moved units and won the company some OEM deals.

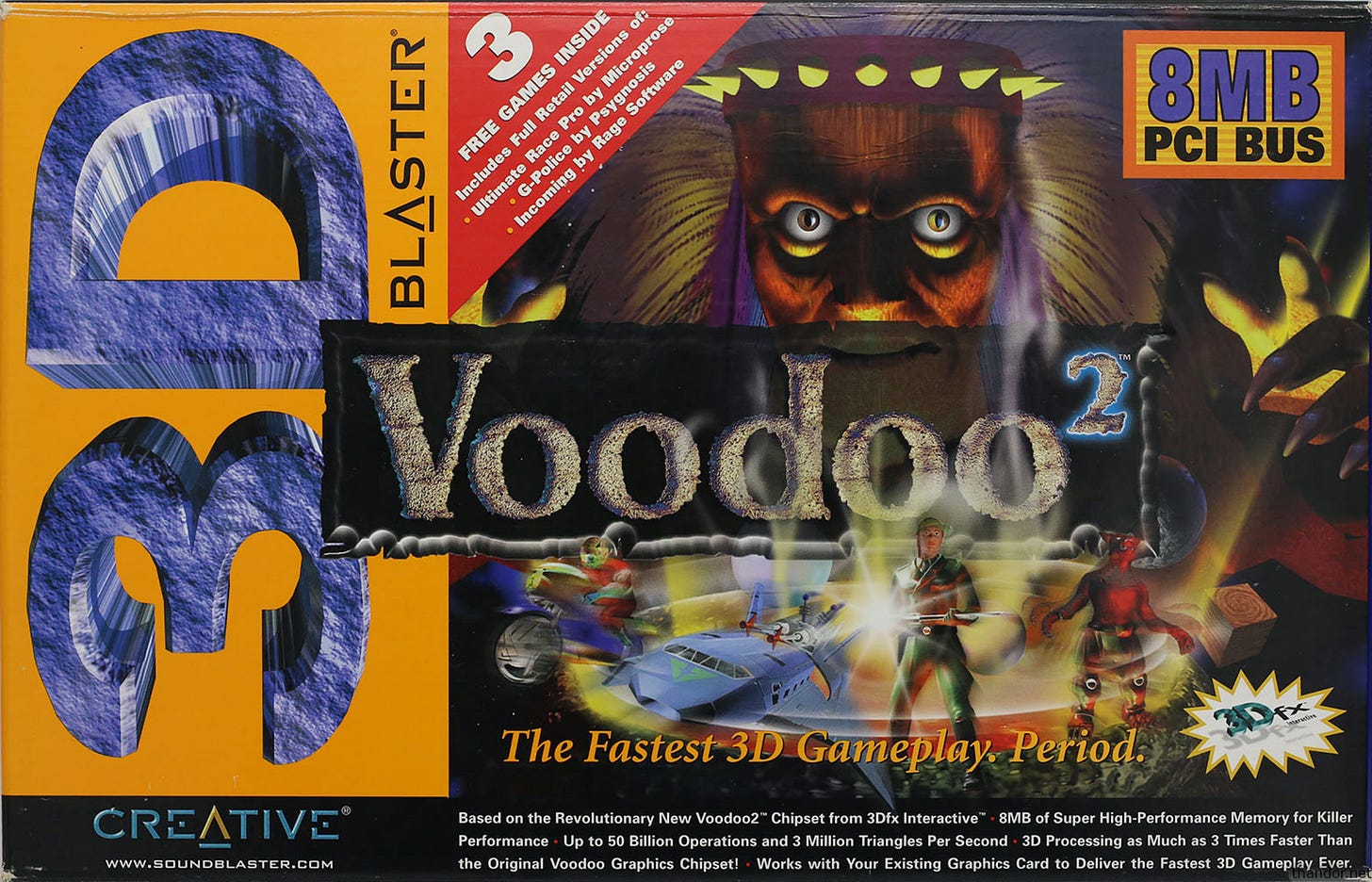

On the 20th of January in 1998, Creative chose to remedy the mistake it had made with their first 3D accelerator, and they released the CT6670, or 3D Blaster Voodoo2. It used the PCI bus, had 8MB of 25ns EDO RAM, and like all Voodoos, supported Glide. In September the same year, the company released the 3D Blaster Voodoo Banshee AGP card (CT6750) as well as the CT6760 PCI card. Depending upon the SKU, these could come with 8MB, 12MB or 16MB of SDRAM. While using the same name, the AGP card was designed entirely by Creative, and it was the only Creative board using a 3dfx chip to be so.

In July of 1998, Creative proved to be a leader in a different market segment with the introduction of HansVision Future 2000 in schools around Singapore. HVF2K featured the HansWord word processor, the HansBrowser bidirectional English-Chinese dictionary, and the HanSight online translator of webpages. Creative had successfully implemented productivity tools on the web, and they’d done machine translation of the web. Truly outstanding for the time.

Beginning in 1997, Creative Labs optical drive bundles began featuring DVD drives and speaker sets (thanks to the acquisition of Cambridge SoundWorks), and on the 10th of March in 1998 these products dropped in price rather dramatically and were expanded in their contents. One example, the Creative Components 700 (the most expensive on offer) included Creative’s PC-DVDx2 drive, Sound Blaster AWE64, the new Graphics Blaster Exxtreme (PCI, 3DLabs Permedia 2 chip, 4MB SGRAM, 64bit data path, OpenGL, up to 1600 by 1200, 60Hz to 150Hz refresh), Creative MPEG-2/Dolby Digital decoder board, and Cambridge SoundWorks’ PCWorks speaker system. This was priced at $479.99. The DVD-ROM drive was $149.99 stand-alone, and the decoder board was $169.99 stand-alone.

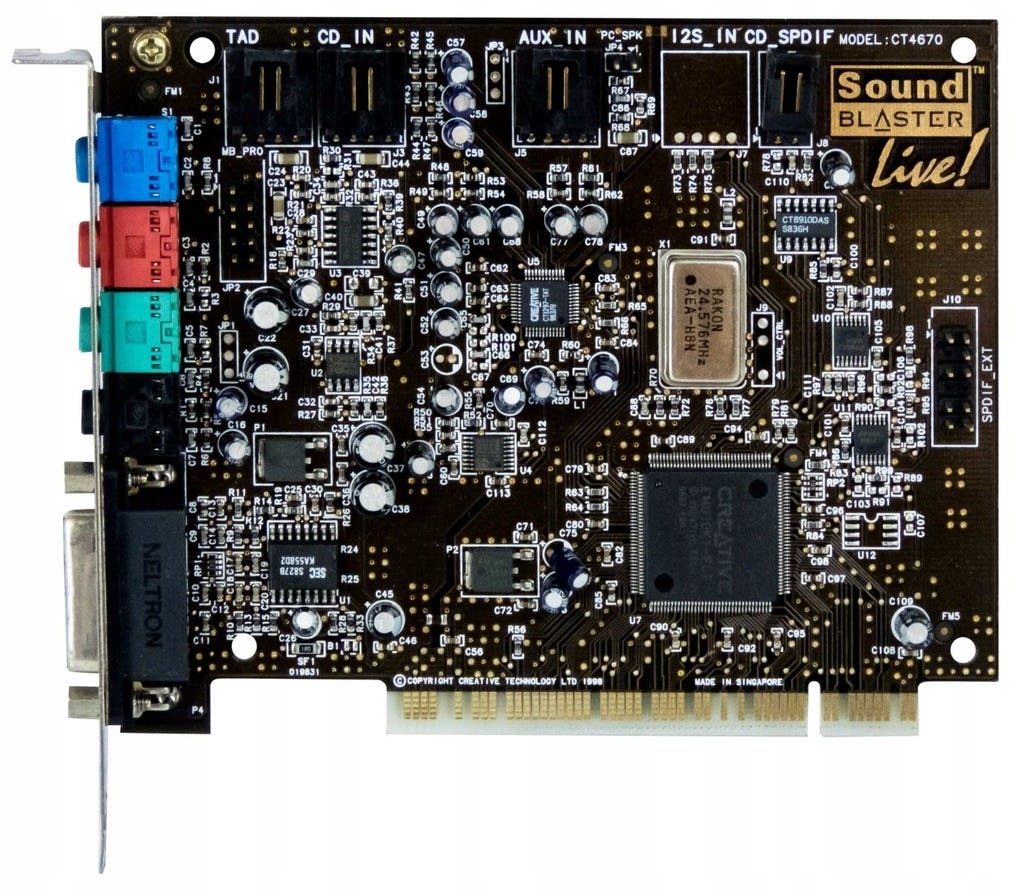

In August of 1998, Creative released the Sound Blaster Live! (CT4670) as a successor to the ViBRA range of sound cards. These were built around the EMU10K1 chip and supported DirectSound3D, EAX (Environmental Audio Extensions) versions 1 and 2, and featured an onboard, 64-voice, wavetable synthesizer though it did use main memory for sample storage. This was a PCI bus card, and it utilized Ensoniq’s TSR for the emulation of Adlib, Sound Blaster, and General MIDI (the adaptation of that TSR was a condition of the acquisition of Ensoniq).

1998 was a year of intense litigation for Creative. The first suit was filed by Creative against Aureal over MIDI caching patent infringements. This was followed by a counter claim of defamation and unfair competition by Aureal against Creative. Creative’s advertising of the Sound Blaster Live! then sparked more lawsuits by Aureal against Creative over claimed falsehoods. By the end of 1999, Aureal had won but had gone bankrupt as a result of legal costs. I am sure it cut quite deeply, but Creative acquired Aureal in September of 2000 for $32 million.

After 3dfx acquired STB, they began making their own cards. As a result, Creative began making, mostly, Nvidia-based cards for video and graphics. There were some exceptions. The Creative 3D Blaster Savage 4 obviously used the S3 Savage 4 chipset, and the Graphics Blaster Exxtreme used chips from 3DLabs. Possibly to prevent the sort of problem they’d had with 3dfx, Creative then acquired 3DLabs in June of 2002. From 1999 onward, Creative would release a handful of graphics cards, some did well and others didn’t, but they were no longer a substantial source of revenue for the company.

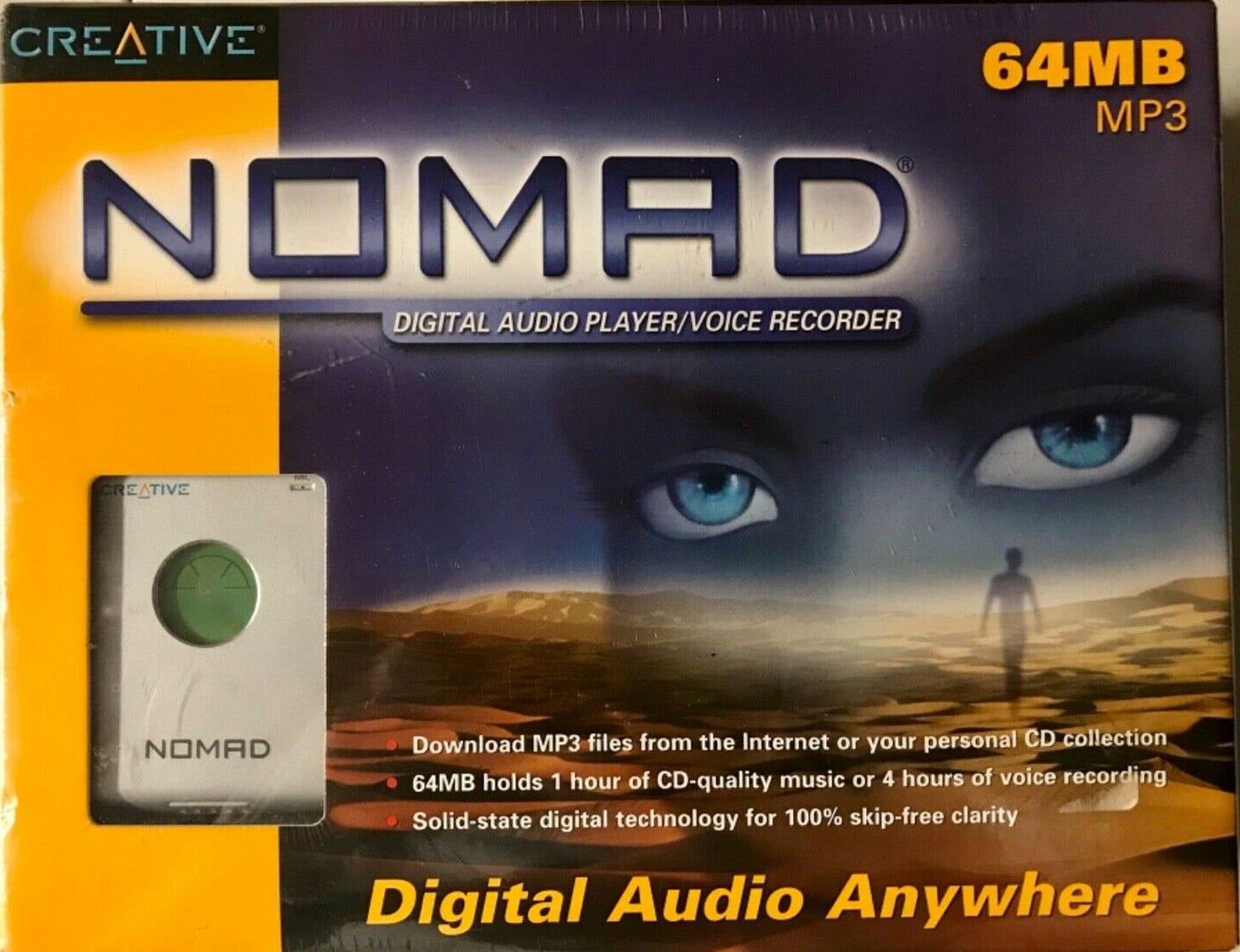

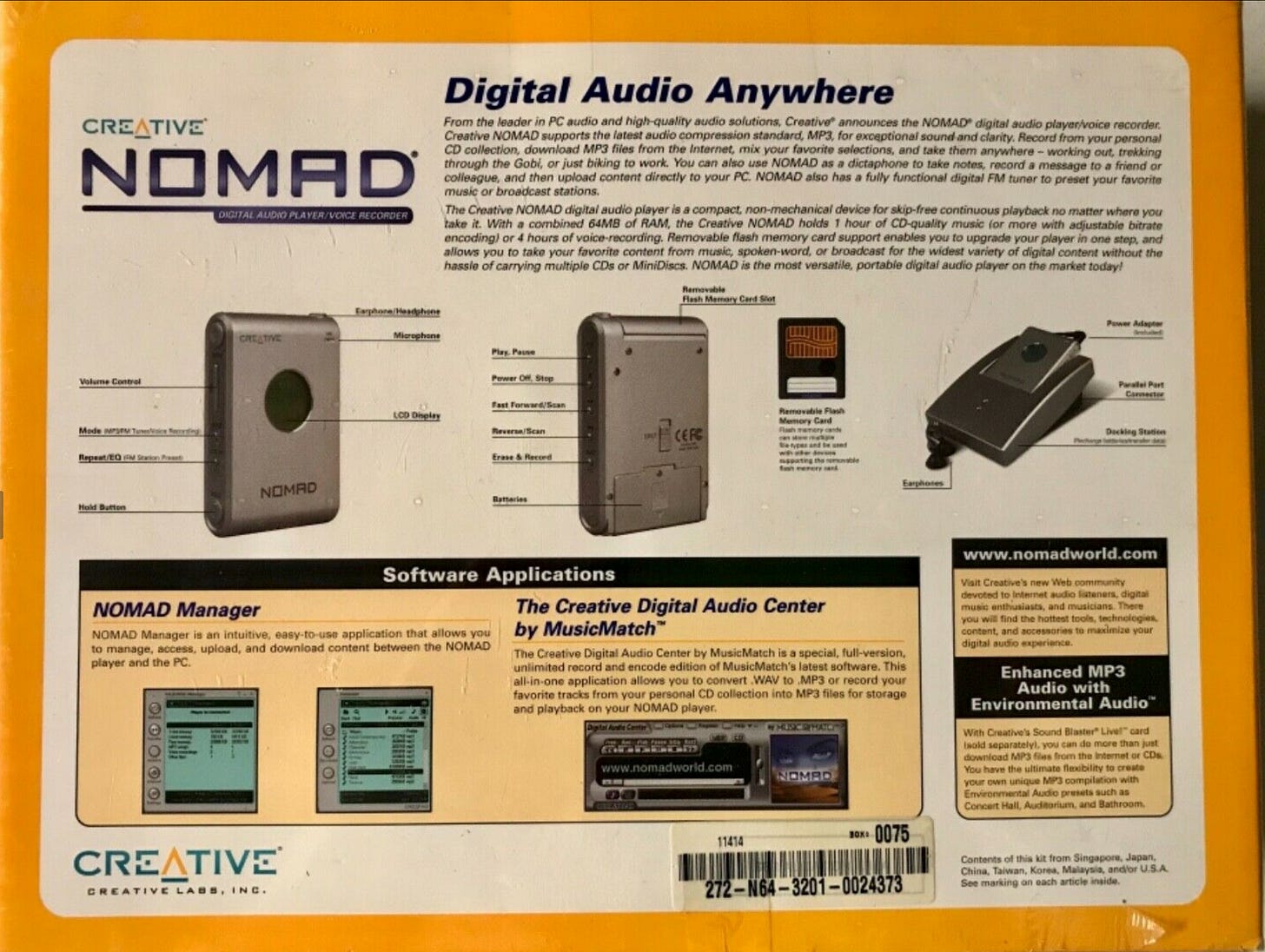

Creative had some great timing with one particular product. WinAmp brought MP3 support to the desktop in 1997, and Windows Media Player 5.2 gained MP3 support in 1998. Creative released the NOMAD MP3 player in April of 1999 for $429. In June of 1999, Napster was born, and MP3s exploded in popularity. The NOMAD connected to a user’s PC via a cradle, and that cradle attached to the PC via parallel port. The device had either 32MB or 64MB of battery backed RAM depending upon the model purchased, with more storage provided by flash media. The NOMAD also provided an FM tuner for those who wished to listen to radio, and a microphone for voice recordings. On the PC side of things, Creative provided both a CD ripper and the NOMAD Manager. The latter of which was for handling the transfer of content to the device. The box proudly claims that 64MB would provide an hour of CD-quality audio, and that’s… well… not true at all. MP3 encoding is quite lossy, and to compress 700MB of lossless CD audio into 64MB infers an incredibly low sample rate. An hour of audio in 64MB would absolutely not be “CD-quality.” Marketing aside, the NOMAD was a cool product.

The NOMAD II launched the following year, and it was well received by the press. This time, Creative used USB 1.1 instead of parallel, 32MB of internal memory, bundled 64MB Smart Media flash, and added EAX support, WMA support, a backlight for the LCD, a wired remote for controls, and slightly better microphone for voice recording. This was followed by the IIc which removed the FM tuner and offered either 64MB or 128MB of internal memory.

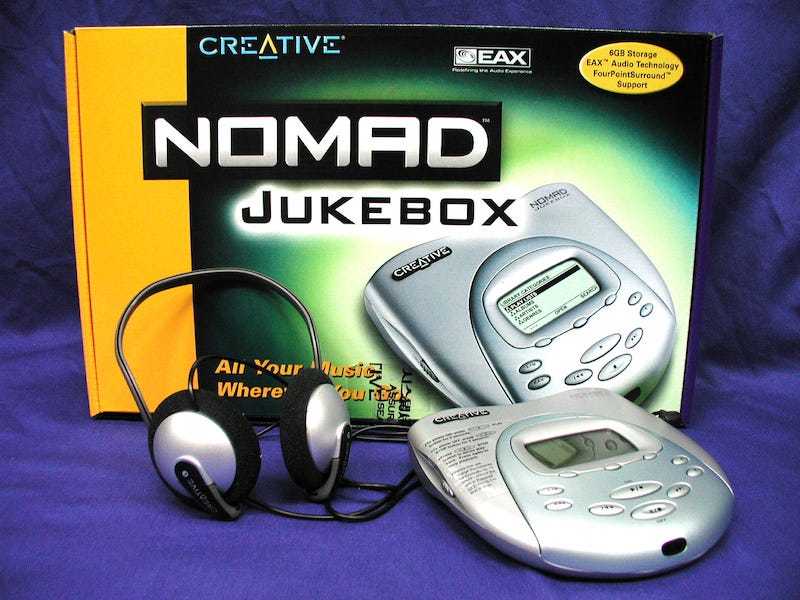

Creative released two further units in 2000, the NOMAD Jukebox and the NOMAD II MG. These also used USB. The II MG returned to the format of the original NOMAD, but it added equalizer presets, ID3-tag support, the wired remote, and the FM tuner returned and now featured. a sleep timer and recording. The NOMAD Jukebox was different. It was roughly the size and shape of a Discman, though slightly thicker, and had a 2.5 inch, 6GB, IDE hard disk in it. The Jukebox also had WAV support, line-in for recording, and two line-out jacks for four speaker systems like Creative’s own Cambridge SoundWorks four point surround. If NiMH batteries were being used, the Jukebox featured a DC jack, and it could charge those batteries. Given the use of spinning rust, battery life was just four hours. For adventurous folks today, the hard disk in this is upgradeable, but the disk didn’t have any identifiable partitions or formatting, and as a result the first 32MB need to be copied with something like dd and then the drive inserted into the Jukebox and the format function used by holding the Play and Stop buttons (or EAX and Down on newer units) during the “loading” sequence.

Following the 2001 crash, Creative became an increasingly audio-only company. Some Chinese/English, electronic, pocketable dictionaries would continue in Asia, but most of Creative’s other endeavors ceased. The company was focused on speakers, headphones, sound cards, and portable music players.

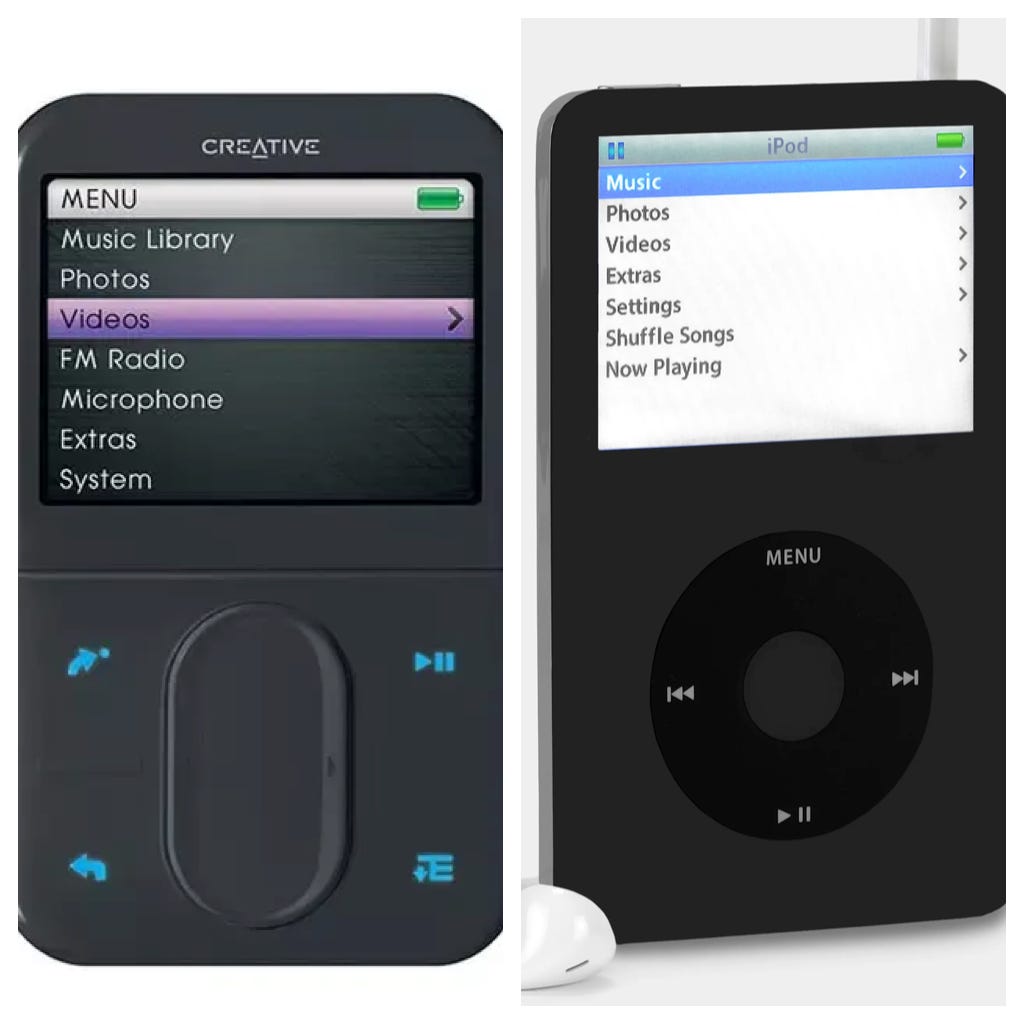

US patent 6928433 was awarded to Creative on the 9th of August in 2005 for the user interface of the Zen and NOMAD Jukebox MP3 Players. This patent had been applied for on the 5th of January in 2001. Creative filed suit against Apple in May of 2006, and the two companies reached a settlement in August with Apple agreeing to pay $100 million.

Time wasn’t kind to Creative. Motherboard audio had become good enough for most people, and fewer than a quarter of desktop users bought dedicated sound cards. Worse, the shift to laptops during the first decade of the new millennium meant that a majority of PC users couldn’t make use of a sound card. Creative voluntarily delisted from the NASDAQ with the last day of trading having been the 31st of August in 2007. The company continued to be listed on SGX-ST. Layoffs of some staff in Stillwater, Oklahoma followed in 2008.

In 2009, 3DLabs and Creative’s Personal Digital Entertainment divisions were combined and reformed as ZiiLABS. This division designed a series of semi-custom ARM chips with 24 to 96 processing units called StemCells. These StemCells were sort of DSPs, and video, audio, and 3D graphics tasks were handled by these coprocessors. ZiiLABS produced at least five SKUs: ZMS-05, ZMS-08, ZMS-20, ZMS-40, and ZMS-50. On the 19th of November in 2012, Creative announced that they’d licensed ZiiLABS technology and patents to Intel for $20 million, and they sold engineering resources and assets to Intel for $30 million. Creative stated in the announcement that they’d retained the patents themselves. The ZiiLABS website was online through 2023, but it later went dormant with a default tomcat page in 2024, and the domain is no longer active. From 2012 forward, the website hadn’t been updated.

Today, Creative is led by Freddy Sim (Sim Wong Hoo’s brother), Tan Jok Jin is the executive chairman, and Ng Kai Wa is vice chairman. The company’s 2024 net sales stood at $62.8 million (12% increase over 2023) with $59.4 million of that being due to audio, speakers, and headphones. The company reported a net loss of $11 million for 2024, down from $17 million in 2023. The company continues to sell Sound Blaster products including both internal and external sound cards, DACs, and amplifiers. Their speakers, headphones, and headsets sell well and have won the company some awards.

Creative rose to dominate the sound card market at a time when there weren’t many options. They made an excellent product, marketed well, and made solid relationships with software makers. The primary issue for the company was that their entire business was built around a single product category, and their attempts to break out of that category weren’t successful. With video cards, they were right on time with a decent product, but the Voodoo was superior. They pivoted and survived that transition only to have 3dfx abandon board partners. They then moved to MP3 players, saw some success, but were beaten by Apple. Today, the company continues in the same niche they once dominated, and they continue to make excellent sound cards. They are simply a much smaller company. Among retro-tech enthusiasts, however, the Sound Blaster 16, Pro, and AWE64 continue to have loyal fans.

My dear readers, many of you worked at, ran, or even founded the companies I cover here on ARF, and some of you were present at those companies for the time periods I cover. A few of you have been mentioned by name. All corrections to the record are sincerely welcome, and I would love any additional insights, corrections, or feedback. Please feel free to leave a comment.