The History of Acer

A Shy Kid Builds the Taiwanese Tech Industry

Stan Chen-Jung Shih was born on the 18th of December in 1944 in Lukang, Changhua County, Taiwan. He was born into a world at war, a tumultuous political environment, and an uncertain future. At the time of Shih’s birth, the island of Formosa was under the control of Imperial Japan, and Lukang was the second largest city on the island. That political reality quickly changed with the Republic of China taking control on the 25th of October in 1945. The Chinese civil war was resumed following the end of the war with Japan, martial law was declared in May of 1949, and the government of the Republic of China fled to Formosa on the 7th of December in 1949.

Shih’s family has run an incense business since 1774 with Stan Shih being the seventh generation to do so. Shih cites the strain of having run the business from a young age as the potential reason for his father’s passing when Stan Shih was just three years old. The young Shih was then raised by his mother, Shiu Lien, who was engaged in a variety of entrepreneurial pursuits. Before dawn she’d knit sweaters. As the city’s economic activities stirred, she’d sell incense, melon seeds, and betel nuts. As the school closed each day, she’d sell pens and stationary to students making their ways home, and then hurry to restaurants with duck eggs; selling Liberty Lottery tickets and incense along the way. Growing up in and around this business was an invaluable supplement to Shih’s education. Selling so many goods in one store with varying profit margins showed him the value of different types of products. While duck eggs made a small profit margin, spoiled easily, and could result in huge losses, they would sell in higher volume than stationary or sweaters, and therefore made more money overall.

While Shiu Lien certainly appreciated help in the store, she wanted her son to study. For his part, Shih was a shy and rather bookish kid. He was interested in the liberal arts, and he worked diligently, studied long hours, and was an exemplary student though his grades in his favorite subjects didn’t necessarily reflect his work ethic. Shih’s personal focus changed dramatically in his junior year at Chang-Hua High School when he earned the Edison Award. This award was granted to the student with the highest marks in mathematics and science. According to Shih, this is what encouraged his later path in life. All of this isn’t to imply that he was a perfect child. Far from it. One summer in high school, he’d told his mother he was going to visit Taipei in the interest of attending a summer school to get further ahead. Instead, he watched a lot of basketball games. As for the school part of that trip, he did actually go to National Taiwan University, but it was to see the athletes Chuang Kwang-Yang and Cheng Chi… not for academics.

Shih graduated from high school in 1962 and initially failed the entrance exam for college. On his second attempt, he succeeded, and he entered National Chiao-Tung University’s Electronic Engineering Research Institute. After earning his Bachelor’s in electrical engineering, he deferred his entrance to the school’s master’s program for military service. After his 13 months of service at the Phoenix Mountain Army Officer’s School as an assistant instructor in physics, he returned to Chiao-Tung and earned his Master’s degree in 1971. His major was semiconductors.

During school, in 1968, Carolyn Yeh said:

One day in my sophomore year, my best friend and classmate told me that she wanted to introduce me to a boy. But she said, “this boy does not know anything; in fact, he is less sophisticated than the least sophisticated boy in our school.” I thought to myself, if he is so out of it, why is she introducing him to me? Whereupon, as if reading my thoughts, she said, “But he is smart! And he is very well-behaved and dependable.” I thought to myself, well, why not? There is nothing to lose. I’ll have a look at him.

Shih was immediately taken by her, and began frequently writing her letters. She, however, wasn’t very taken by Shih. Shih wasn’t dissuaded and kept pursuing her. Sometimes, Carolyn’s classmate would shame her into responding, and failing that would just sit her down and force her to respond. Carolyn’s mother then intervened occasionally inviting him for dinner with the family. It worked, and the two were engaged in 1969 and were married on the 28th of September in 1971.

Two things stand out about Shih at this point in his life. The first is that there was tremendous pressure for students in the ROC to go to the USA for graduate school. Shih resisted this, and chose to stay on Formosa. He cites not wanting to leave his mother, and also having a bit of a contrarian streak as his reasons. The second thing to note is that he was personally transformed from a shy and bookish kid into an outgoing and assertive man. He was the valedictorian, and the president of the table tennis club, the volleyball club, the photography club, and the Chi-Chao club.

After school, his contrarian tendencies evidenced themselves once again. While many of his peers went to work for companies like TI, Philco, or Zenith, Shih chose to accept an offer from Unitron. There, he designed, developed, and created marketing material for the first technological product created entirely in Taiwan, a desktop calculator. The product came to market and wasn’t terribly successful, but it was enough to propel Shih’s career. He then left Unitron to become one of the founding members of Qualitron making hand-held calculators in Taiwan with TI chips. The most popular product that they made was their scientific calculator based upon Rockwell International components that could perform sine, cosine, and trigonometric functions. While surely, Shih had a bias, he reports that Taiwan moved faster than Japan and had higher quality. This led Qualitron to become both an OEM and ODM (original design manufacturer), and in the ODM world, they were a pioneer. Rockwell placed their first order from Qualitron in 1973. Shih took charge of R&D, manufacturing, procurement, and warehousing for OEM and domestic markets as the company’s VP. Then, Rockwell began selling the 4bit PPS4 (Parallel Processing System 4) CPU, and then the 8bit PPS8. Shih saw this a huge opportunity, attended a seminar and training session at Rockwell, and he brought what he’d learned back to Taiwan. Even at this early time, he and others at Qualitron saw the microprocessor as something that would bring about the next industrial revolution. Qualitron immediately moved to microprocessor based technologies, and began selling the MOS KIM1.

Qualitron’s success was short-lived, however, as Qualitron’s parent company had significant investments in the textile industry. Around 1975, Taiwan’s textile industry suffered a steep decline, and took Qualitron with it. With Qualitron’s financial position irrecoverable, Shih knew he needed to start a new company. Carolyn Yeh and Stan Shih invested 500,000 of their own New Taiwan Dollars, (about $13,000 USD, or around $74,000 in 2025), with help from Shih’s mother, and Shih’s former coworkers George Huang, Fred Lin, Li-Chun Shen, Chin-Chuan Tu, and Kenneth Tai to put in $100,000 each. They founded Mutlitech International Corporation in Hsinchu City on the 1st of August in 1976. They hired eleven employees, and began distributing electronic components, designing products for other companies, and engaging in consulting work in the field of microprocessors. Some of their early designs included a 4bit handheld game, telephones, and terminals. By 1978, Multitech had established the Hung Ya Microprocessor Learning Center in collaboration with Chaun Ya Electronics where more than 3000 engineers were trained, helping to build the Taiwanese industry.

In Taiwan in 1976, there was no real widespread understanding of microprocessors, there were no venture capitalists, friends and family were loathe to invest in markets they did not understand, and Taiwanese banks didn’t want to be involved in startups. Shih had to get creative. The solution he devised in those early years was for employees to lend 10% of their salaries back to the company in exchange for a bonus. All of the employees were also shareholders of the company, the companies financial statements were published internally every quarter, and there was an internal stock market. Shih cites this as having been essential for the early company not only in allowing the company to raise much needed funding but also in motivating the company’s employees; everyone won if the company won, and everyone lost if the company lost. This was starkly contrasted against the formula of the time in Taiwan of having strictly family owned and operated companies. Having just watched that model doom his previous employer, it’s understandable that Shih would avoid that as much as possible.

In 1981, Multitech released the Micro-Professor MPF-1. This was a Zilog Z80 development board in a plastic book-like case. The initial version of the board shipped with a Z80 clocked at 1.79MHz, 2K RAM, 2K ROM monitor, a six-digit seven-segment display, a beeper for sound, and a hexadecimal 36-key keyboard reminiscent of a calculator. Later the same year, the company released an upgraded ROM of 4K that included TinyBASIC. Models sold with this new ROM became the MPF-1B and the original retroactively became the MPF-1A. The Micro-Professor MPF-1 initially sold for $149. Interestingly, a journalist at Chip magazine in Germany wrote an article about the MPF-1 but listed Microtek as the name of the company producing it. Readers were then sending money to Microtek, and Microtek would pass the money along to Multitech who then fulfilled the orders. The product’s success led to many other companies selling the MPF-1 around the world.

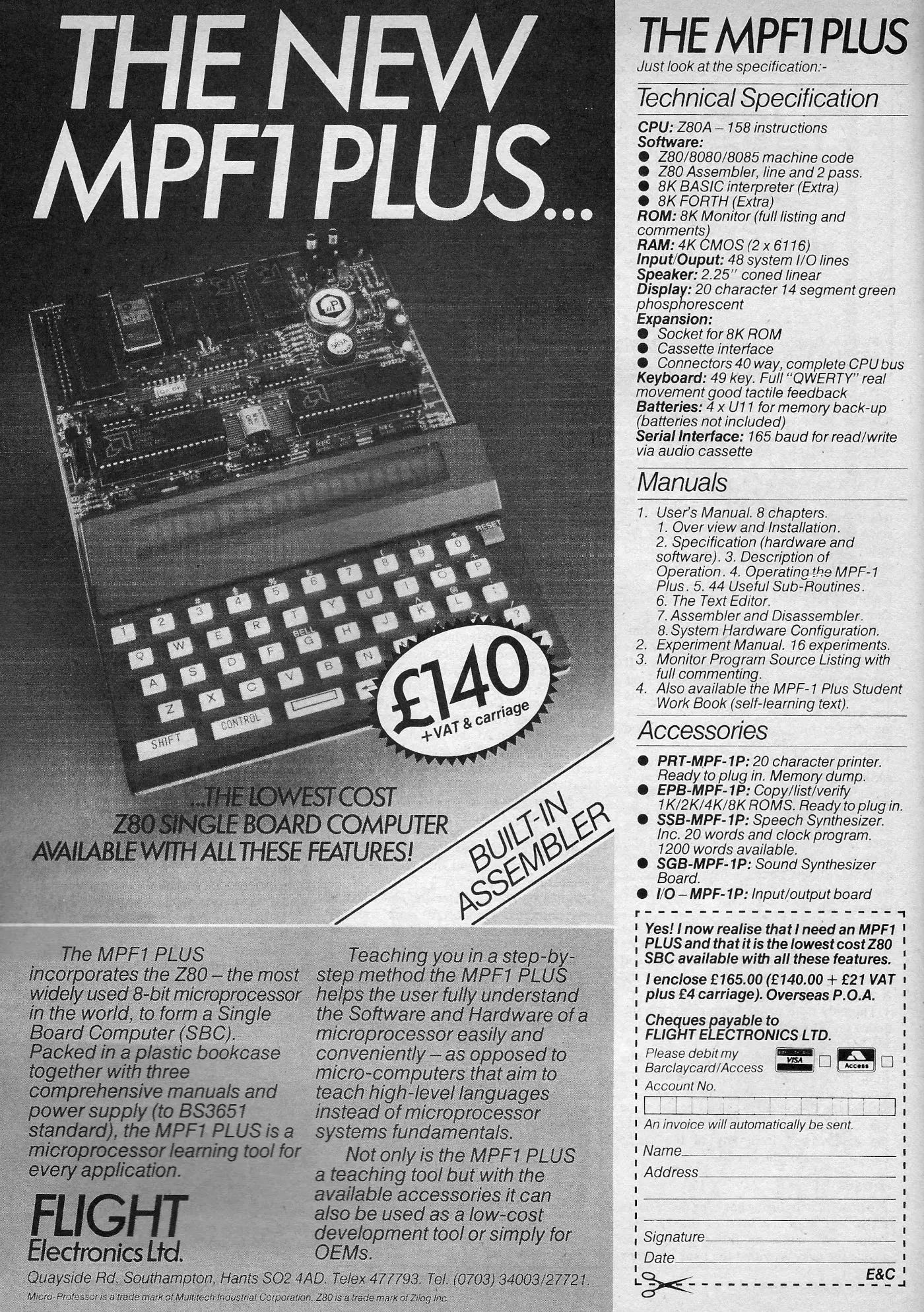

Naturally, with the success of the little computer, successors followed. The MPF1 Plus released in the summer of 1982 expanded language support, allowed for ROM expansion, brought about a much better keyboard, and with an I/O board expansion, the MPF1 Plus could become a very competent microcomputer.

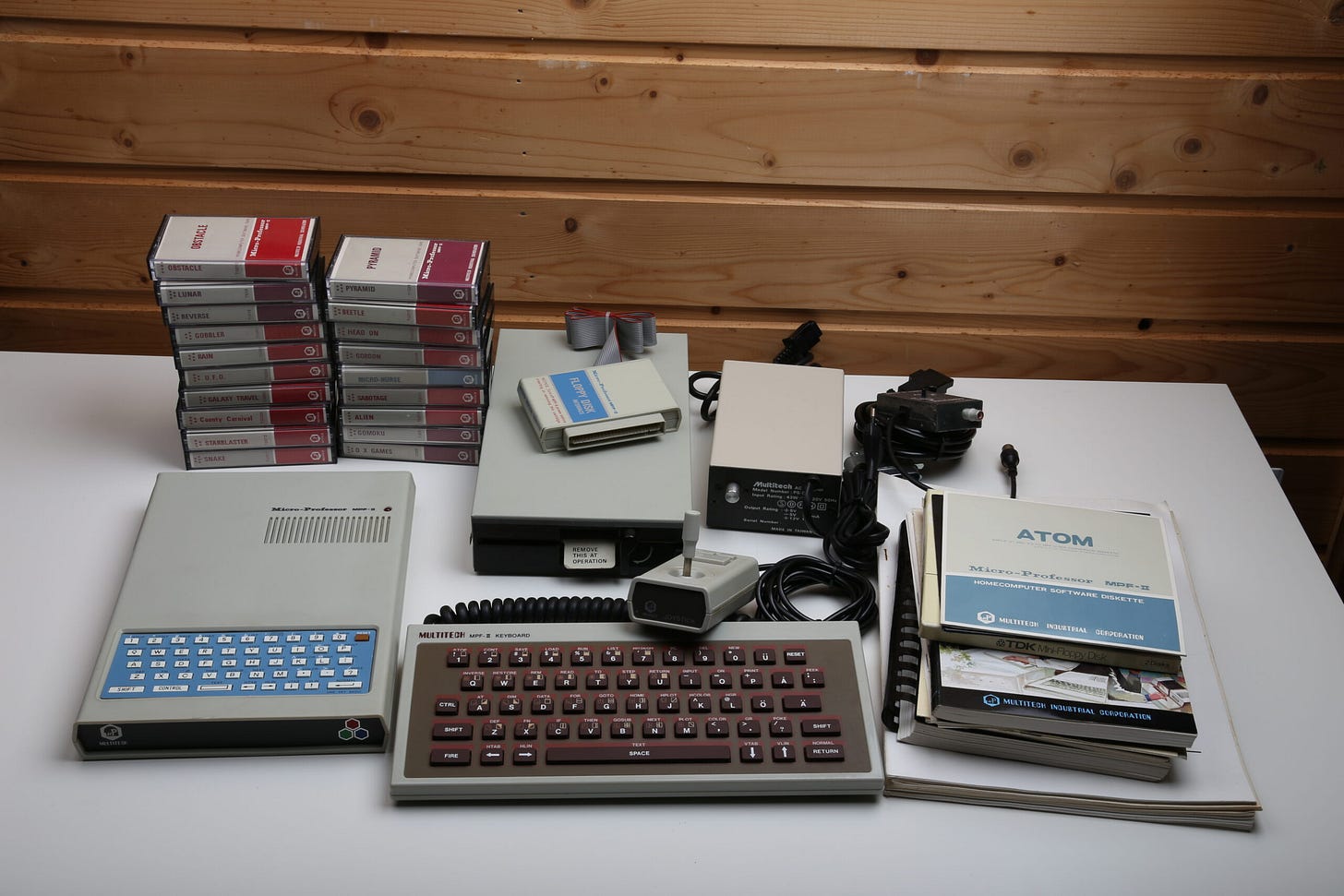

Multitech released the Micro-Professor MPF-II in 1982 as well. This was the company’s first true personal computer product, and it was quite unique. The most obvious bit was the design. It was just a modest metal slab with a chiclet-style keyboard on it. The second unique bit was that this was an Apple II clone machine. The MPF-II was built around the 6502 at 1MHz, 64K RAM, and 16K ROM. It had a text mode of 40 columns and 24 rows with 7 by 5 pixel characters. There were two graphics modes both with six colors: 48 by 40 or 280 by 192. Sound was a single channel of 1bit. The computer had plenty of connectors: keyboard, joystick, printer, cartridges, audio in/out (cassette), composite video out, RF out, and Multitech offered a 55-key full-size keyboard, a floppy disk drive, a thermal printer, a dot-matrix printer, and joysticks. Importantly, neither the MPF-II’s cartridge slot nor its joystick connector were compatible with those of the Apple II. The text mode wasn’t either, and on the MPF-II all text was drawn by software rather than hardware, and this was due to Chinese language support. A Chinese character generator would have been prohibitively expensive. The keyboard and second graphics buffer were also at different addresses which meant that Apple II games could not be played on the MPF-II. Where the MPF-II and Apple II were compatible was in their BASIC dialects.

Multitech avoided legal trouble with the hardware and software of the MPF-II, but the translator they’d hired to make the English-language manual largely copied the manual of the Apple II. Multitech only discovered this when the MPF-II was held up in US customs for plagiarism.

To promote the Micro-Professor MPF-II and the upcoming MPF-III, Shih traveled to the USA for Comdex. The Compaq Portable was the talk of the show as it had just recently been announced, and the show largely centered on machines from HP, Wang, TI, and IBM with some Japanese companies making strong showings as well. Shih immediately knew that he should be making IBM PC compatible computers rather than somewhat Apple compatible computers, but his young company had already begun the development of the MPF-III, they had partners involved in the MPF-III, and they lacked the required talent for a PC project anyway.

The Micro-Professor MPF-III was to the Apple IIe as the MPF-II was to the Apple II. It featured a MOS 6502 at 1MHz, 64K DRAM, 2K SRAM, 24K ROM, and could make use of DOSs for the Apple IIe such as Apple DOS or ProDOS. For display, it supported NTSC composite out or RF out, and for other ports, it had cassette, printer, joystick, and external speakers. Internally, the MPF-III had six expansion slots, and it could use a Z80 CP/M card. Display modes included 40 columns by 24 rows, 80 columns by 24 rows (if an 80 column card was installed), 40 by 48 pixels, and 280 by 192 pixels. If a user chose to purchase floppy disk drives from Multitech, these drives were in an expansion unit that sat comfortably atop the MPF-III. Like its predecessor, the MPF-III included a Chinese-language BASIC that was based upon AppleSoft BASIC and many of the changes to support Chinese hindered overall system compatibility with the Apple IIe. The MPF-III was announced in 1983, and it was released in early 1984.

In 1983, multiple companies were requesting OEM and ODM services from Multitech, and these companies didn’t like the idea of working with a company that directly supplied their competition. Minister Li Te Su and Stan Shih traveled to the USA to learn the venture capital market, and upon their return they established the Hung-Ta Venture Capital Corporation. This was the first VC firm in Taiwan (as far as I can tell), and the company started getting funds together to found Continental Systems Inc, a subsidiary of Multitech, that did OEM exclusively for International Telephone & Telegraph (now ITT Inc). Continental Systems would later become Acer Peripherals and then become BenQ in 2001. The first CEO of Continental Systems was Cheng-Tang Chen. An important note is that these were separate companies who shared only stockholders and equities. In day to day operations, they weren’t connected.

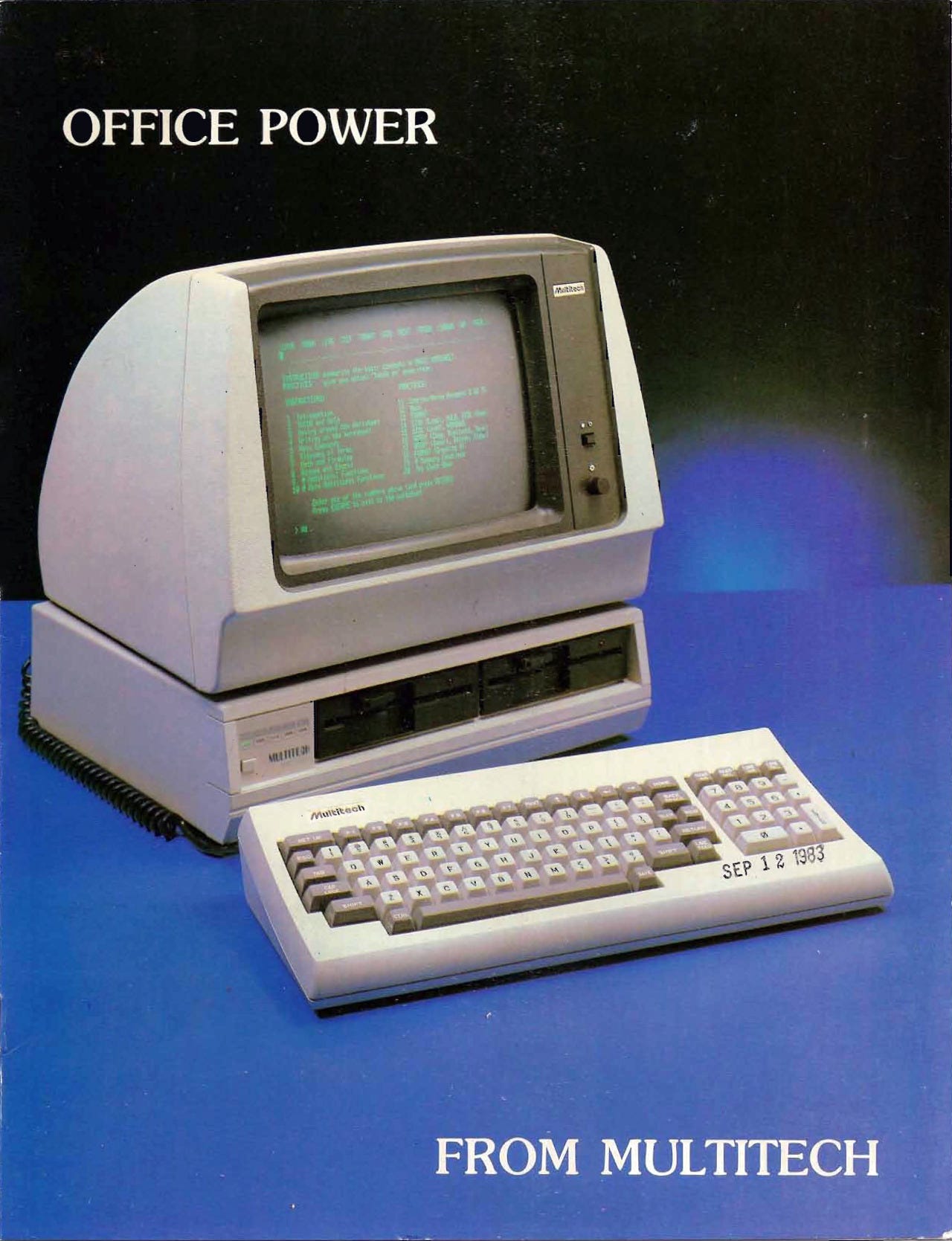

Getting away from hobbyist machines, the last 8bit computer from Multitech was… interesting. The MIC-500 released in late 1983 retailed for $1599 and came with a Z80A clocked at 5MHz, 64K RAM, two 5.25 inch floppy disk drives, two RS-232C ports, a parallel port, BASIC, CP/M 2.2, WordRight, Magic Worksheet, Analyst, Qsort, and NAD. This machine could optionally be purchased with a 33MB HDD and a 12 inch monochrome monitor. This was a networked office machine, and it was targeted solely at the commercial market.

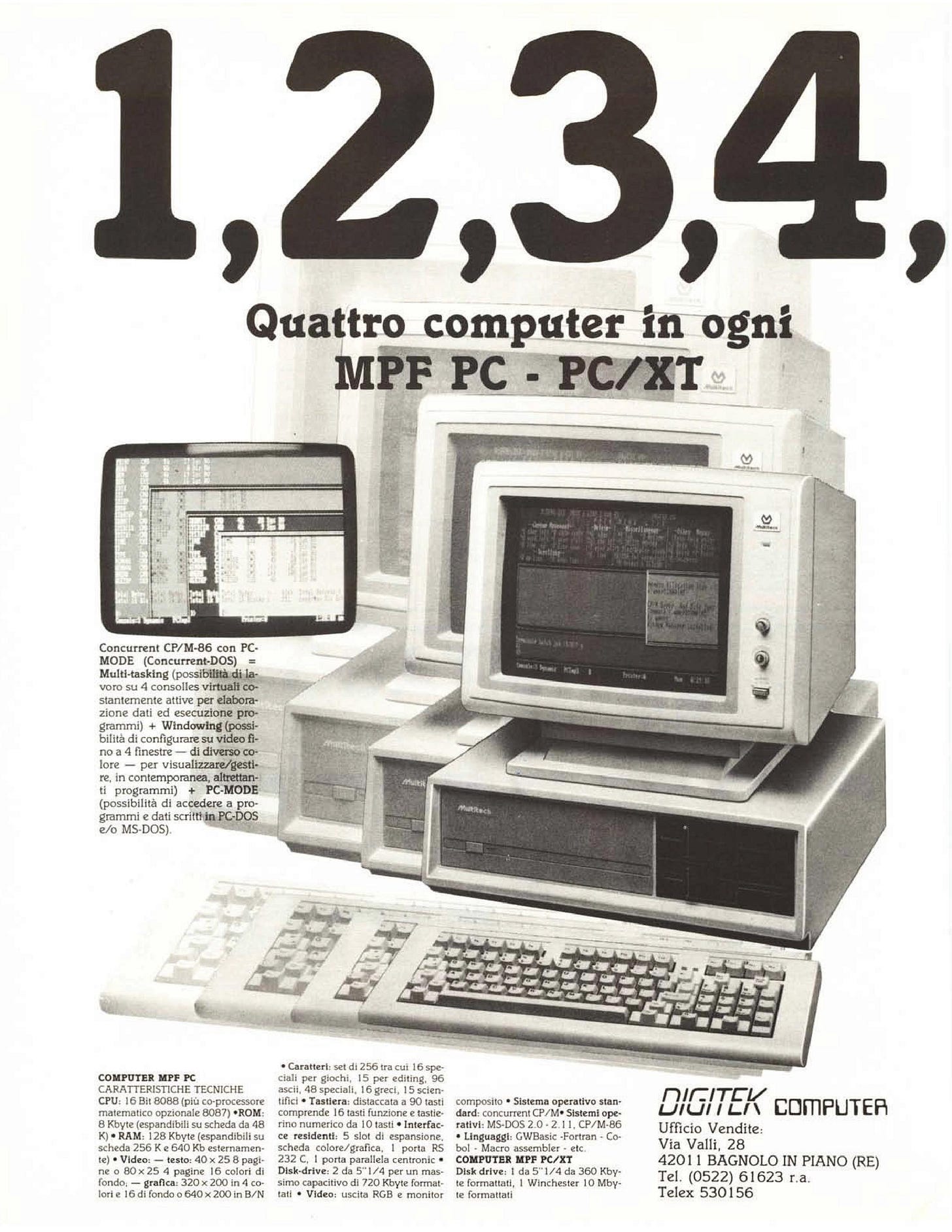

The same year that the company’s last 8bit machine launched, Multitech’s first 16bit computer launched. This was the MPF-PC. As with most PC compatibles, it shipped with an Intel 8088 CPU at 4.77MHz, optional 8087, an 8K ROM (expandable to 48K), 128K RAM (expandable to 640K), and five expansion slots. For video, the machine was capable of full CGA via composite or RGB out. The machine also had an RS-232 port, a parallel port, and two 720K 5.25 inch floppy disk drives. An optional 10MB Winchester disk drive was available. Where this machine was significantly different was that it shipped with Concurrent CP/M as the standard OS, allowing up to four applications to be run in windowed virtual consoles. MS-DOS 2.0 and 2.11 were also available. The choice of Concurrent CP/M which was, Digital Research assured Shih, fully MS-DOS compatible cost Multitech $30 million NTD to license (or $761035 USD, roughly $2.5 million in 2025). What Multitech learned was that this was really more like 99% compatible, and the company ran into some issues. They also had issues with the I/O controllers they chose (AMD rather than Intel) that had some minor compatibility issues. These were mistakes that would not be repeated.

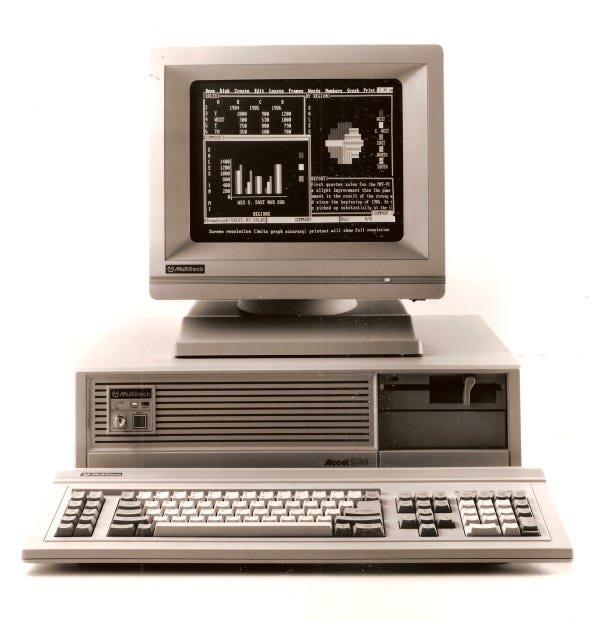

In 1985, Multitech launched four machines: DCS-570 Bilingual Workstation, Popular 500, Plus 700, Accelerator 900. The Popular 500 and Plus 700 were 8088-2 machines that were XT compatible and priced from $859 to $1395 in the USA. The DCS-570 and Accel 900 were AT compatible machines starting at $2395 USD. From what I can tell, it would appear that the DCS-570 differed from the Accel 900 mostly in language support, and shipped with Chinese-localized software. Otherwise, the Accel 900 was built around an 80286 clocked at 10MHz, 512K RAM (expandable to 1MB), a 1.2MB 5.25 inch floppy disk drive, MS-DOS 3, and optional 40MB HDD.

In 1986, Multitech wanted to break out of being a low-cost supplier and enter the workstation market. To do this, they needed some expertise. Multitech had an investment in Suntech in the USA, and Shih Ke-Chiang was leading a team there to build a Motorola 68000 workstation. This project ran out of money, and Stan Shih sent a team to the USA under the direction of Jonney Shih (no relation to Stan Shih) to work on cost reduction and learn 32bit systems. It all worked, and they had a 32bit workstation in a short time. It just wasn’t based upon the Motorola 68000. To bring the workstation to market, Multitech chose to partner with Unisys. This partnership really had two parts. Unisys bought PCs from Multitech, and Multitech got the expertise they needed to enter higher-end markets. The result from Multitech was the 1100 built around a 16MHz 386SX, 1MB of RAM (expandable to 8MB), a 1.2MB 5.25 inch floppy disk drive, four 16bit ISA slots, four 3.5 inch internal drive bays, two serial ports, one parallel port, an IDE interface, and PS/2 compatible mouse and keyboard ports. The machine shipped with GW-BASIC, MS-DOS, and Windows/386. The Multitech 1100 was announced just one month after the Compaq Deskpro 386 (the Deskpro was September, the 1100 was October), but it accomplished two things that stand out. The 1100 was the first Chinese-language computer with a 386, and it was available at roughly the same time as the very first English-language-only 386. Then, it was also about half the price of the Compaq (or lower if the user didn’t want a hard disk).

Multitech had become a somewhat unknown international brand whose products made their way to the market under other brand names. While the company had been growing and seeing great profits, they wanted to expand. There were, however, many companies around the world with extremely similar names. Selling in the USA was problematic as there was a Multitech making modems in the USA. The Netherlands and Germany also had companies with same name although Multitech did have a branch in Dusseldorf already. Multitech couldn’t decide on any specific name, so Shih had some of the software engineers write a program that would pseudo-randomly choose four or five letters in two syllables. This generated quite a few options. The legal department checked registrations for the names the executive team liked and none of these names were available. They then reached out to Ogilvy & Mather whose art director in Australia suggested Acer. Shih enjoyed one of the meanings of the word in Latin, energetic, and the name was chosen. The company quickly became Acer Inc. With the name situation handled, they could expand into new markets without fear of litigation over the name, and expand they did, gaining a wider presence in Europe (picking up clients like Nokia, Ericsson, Philips, Bull), East Asia, and North America.

From founding to 1988, Acer’s revenues had doubled every year. In 1988, Acer was listed on the Taiwan stock exchange, which serendipitously, had just migrated to the Computer-Assisted Trading System (CATS). This had a large impact on staffing at Acer. All (or almost all) employees had invested in company stock by 1984, and in 1988, many of them suddenly found themselves with quite a bit of money. Young people flush with cash tend to be willing to take some risks, and they started leaving. Some of them got better job offers and some started new ventures. By 1989, this turnover had changed the company culture, and opportunities for advancement began to dwindle. This pushed some of the more ambitious folks to leave as well. A positive side-effect of this change was that the company became a bit more mature. While bureaucracy is something I usually mention in a negative light, there isn’t really any other known way to structure a large multinational corporation. This change allowed Acer to more effectively organize its efforts across the globe.

In the mid-1980s, Jonney Shih became the head of R&D. He’d been instrumental to Acer from its founding. Jonney Shih joined Multitech upon his completion of graduate school, and led the team who’d developed the MPF-I and MPF-II, he’d led learning trips to the USA, and he’d served as the editor of Acer’s publication The Words of the Gardener. Stan Shih describes him as being more intelligent than himself, affable, capable, and forbearing. His management style was decidedly one of empowerment. People working for him could pursue their interests, exercise their talents, and he was well liked. By 1987, he’d become the leader of the PC Division of the company.

Desktop computers began pouring out of Acer with Acer branding. The Acer 710 was an XT-class machine released in 1987 with an 8088 at 10MHz, the 900 was a rebranded Multitech Accel 900 that remedied the earlier model’s shortcomings, the 900/12 increased the 286’s speed to 12MHz, increased the base RAM to 2MB and the limit to 16MB. The Acer 910 retailed for $1795 and offered a 10MHz 286, 512K RAM (expandable to 1MB), a 20MB hard disk (optionally 40MB or 80MB), 1.2MB 5.25 inch floppy disk drive, four 16bit ISA slots, two 8bit ISA slots, two RS-232C ports, one parallel port, a light pen port, and MS-DOS 3.2. The 912 was roughly the same machine with a 12MHz 286. The 915 brought the 912 a higher RAM limit of 16MB but decreased the number of available ISA slots to just four 16bit slots.

The Multitech 1100 was now the Acer 1100, and the only real change was the availability of larger hard disks. It did gain some siblings with the 1100/20, 1100/25, and 1100/33 where the second number indicated the speed of the 386. The 1100/33 with 4MB of RAM started at nearly $7000 USD while the base-model was around $2000 USD.

Then there was the Acer LAN 500 which was a diskless PC-compatible intended for use a thin client with its ARCNet LAN card. IT shipped with an 8088, 512K RAM, monochrome graphics adapter, and monochrome monitor. An upgraded model of the LAN 500 was the LAN 900 with a 286 and some 16bit ISA slots. From here on, with the number of SKUs expanding so rapidly… I will not make you suffer coverage of every single one, but rather just the most notable.

By 1992, the price of the 1100 series (now AcerMate) had fallen to $900 at the low-end and around $2000 at the high-end. At the start of 1993, Acer introduced the Acros. The base model, at $1395, shipped with a 486SX at 25MHz, 4MB of RAM, a Cirrus Logic SVGA adapter with 1MB of VRAM, a 170MB hard disk, and a 14 inch SVGA monitor. For software, it shipped with Windows 3.1, Microsoft Works, Quicken, and Prodigy. The best model in the line up featured a 486DX2 at 66MHz at a price of $1945, and this one featured an optional upgrade to a Pentium.

The AcerPower line up built upon the Acros adding 256K CPU cache to the DX2, increasing the disk size to 420MB, and allowing up to 64MB of RAM. The top AcerPower 9000T shipped with a 60MHz Pentium, up to 192MB of RAM, a 256K CPU cache, a 540MB HDD, two PCI slots, Windows 3.11, and MS-DOS 6.2.

Around the end of 1993, Acer had long been making machines for companies like NCR and ITT. Shih had achieved this by communicating to these customers that Acer’s scale ensured consistent supply, lower pricing, and high product quality, but he also promised that his company would honor and protect intellectual property and trade secrets. Then, IBM approached them. Then came Apple. Shih had to take a trip to the Sunnyvale to gain Apple’s business. Apple’s products were distinct, used a different architecture, and used different software. Shih had to explain that it would take a bit more time to develop what they were requesting, but Acer got the business and kept Apple updated on their progress. Then came Dell, and Shih once again had to take a trip to the USA. Again, he succeeded.

1994 saw Acer introduce their Multimedia PCs with the Acros name. True to the specification, these machines all featured a 486, 4MB of RAM base (up to 36MB), 1MB of Video RAM, CDROM, Soundblaster audio, PS/2 compatible mouse and keyboard, and a hard disk of 210MB or greater. The software listing hits the nostalgia button quite hard: Windows 3.1, Microsoft Multimedia Works, Microsoft Entertainment Pack, Microsoft Productivity Pack, Microsoft Encarta, Microsoft Cinemania, Microsoft Sound Bits, Microsoft Multimedia Golf, Intuit Quicken, Prodigy, America Online, and Phoenix Micro-Fax.

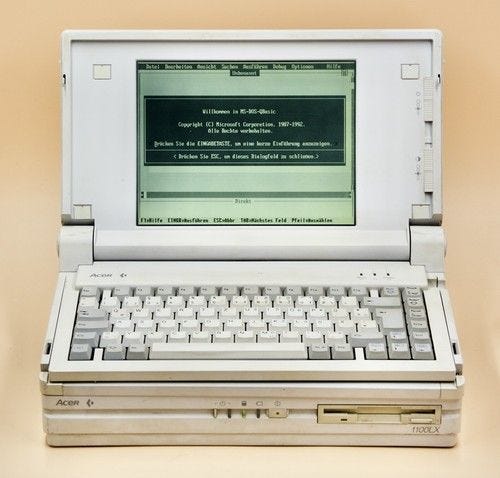

Acer had begun offering laptops in 1991 with the AnyWare series. An interesting model, the 1100LX, had a detachable keyboard for use on a desk and offered a 386SX at 16MHz, 1MB of RAM (expandable to 5MB), a 1.44MB floppy disk drive, a 40MB HDD, VGA, and an optional 2400 baud modem, expansion chassis, 10-key, and carrying case. This machine was thick and weighed in at almost 15 pounds. A slimmer and more reasonably sized offering was the Acer Acros 325SE released in 1992.

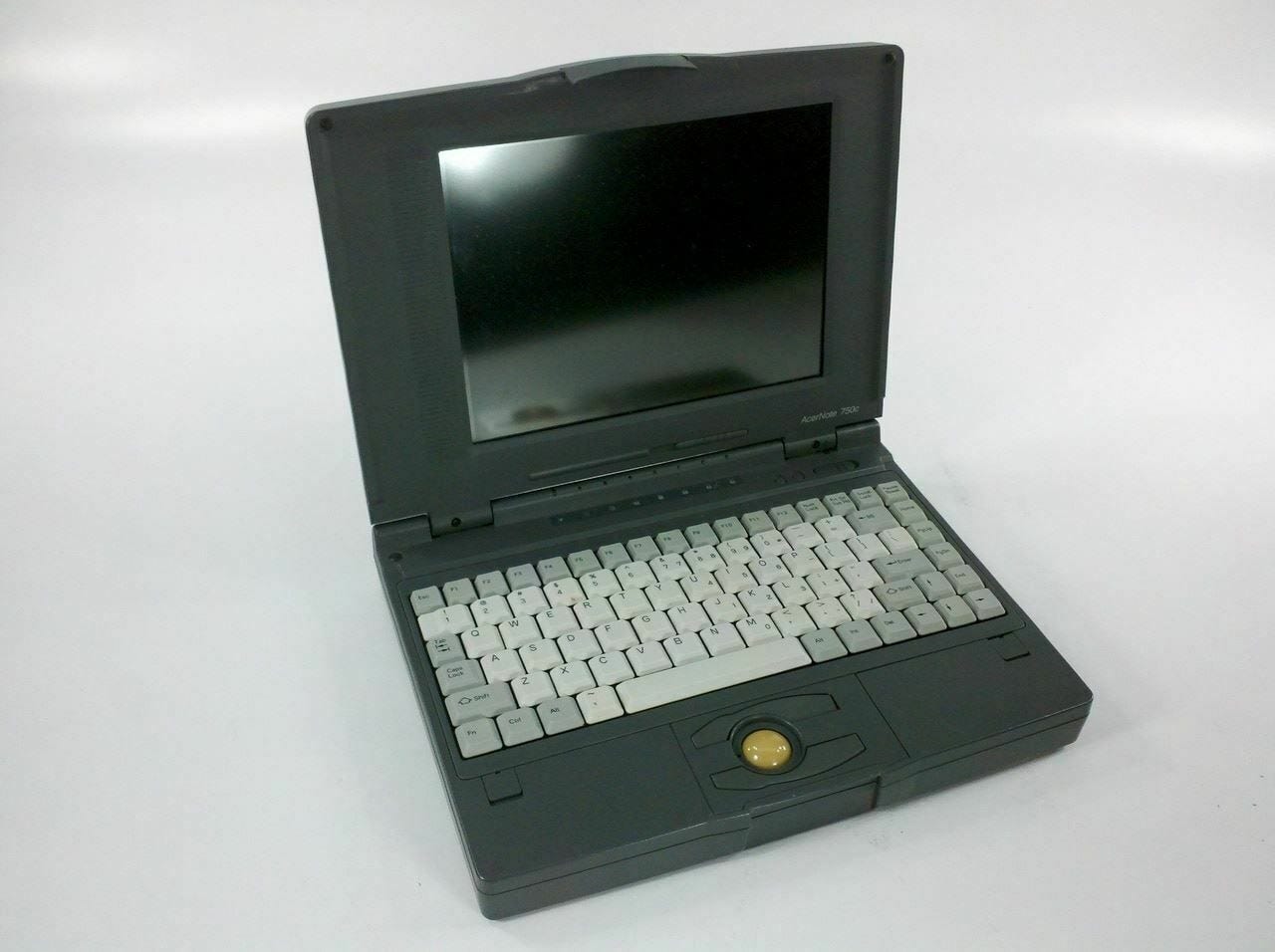

These were followed by the AcerNote series built around the 486 in 1993 which featured PCMCIA, and in higher SKUs, VLB accelerated graphics.

Much of the success of Acer in manufacturing for other companies had been due to Stan Shih’s Smile Curve. Essentially, after analyzing the computer market, Shih realized that the real money to be made was in R&D, sales, and service. Branding and marketing were less valuable, design and distribution less valuable still, and manufacturing was the least lucrative. With the Smile Curve understood, it’s much easier to understand how Acer had been successful in the past, and why Acer moved into designing, manufacturing, and selling more machines under their own branding later. Gaining expertise in hardware was relatively easy as large companies were all too happy to be free of the burden of manufacturing. This was a cost center for them. As Acer gained that expertise and established reliable revenue streams, they could invest in the other parts of the curve. Shih coupled the Smile Curve with his 1-2-3 philosophy. The customer was number 1, the employee was number 2, and the stakeholder (shareholders, banks, suppliers, society at large) was number 3. By keeping customers happy, the business remained in business. By keeping employees happy, the business continued to function well. With both customers and employees happy, the stakeholders could become wealthy. In 1995, Acer’s revenue per employee was $463,000 USD, and the average salary was around $15,300 USD. Yet, as employees were also shareholders, thousands of Acer employees were millionaires. The company also offered a profit-sharing plan, and all employees were entitled to bonus shares. In the best years, an employee could earn several years’ salary in a single bonus.

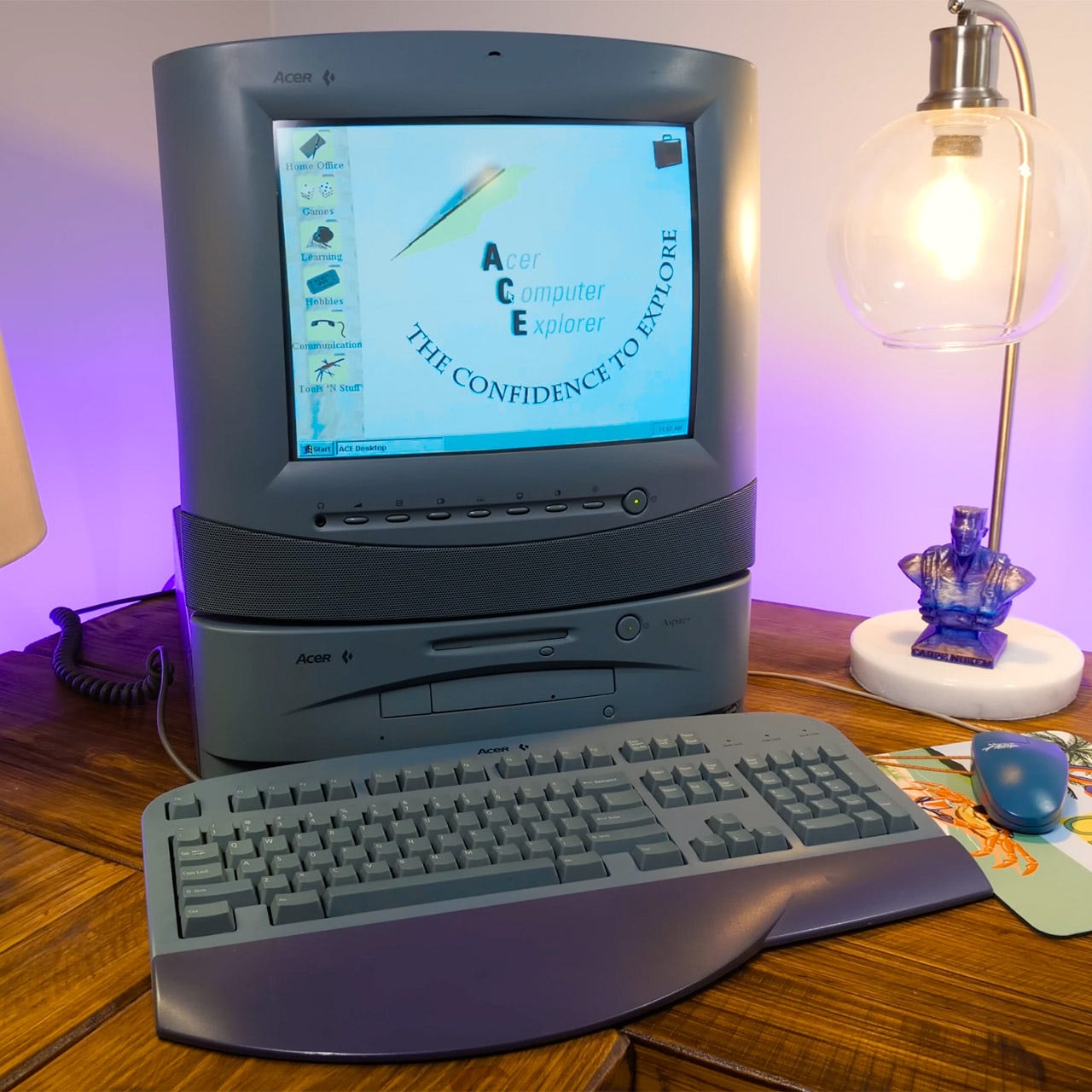

In September of 1995, Acer introduced the Aspire line of computers. These were machines targeted at casual home users, and the first came in a case designed by Frog Design who’d also designed the Sony Walkman WM-2, the Apple IIc, and the NeXTcube. For those customers not wanting the emerald green look, the Aspire was also available in charcoal. This line was around $2200 without a display. Specifications started with a 100MHz Pentium and 16MB of RAM. The Aspire line was successful, and it continues to this day in a variety of form factors, price points, and color options.

By 1996, Acer was worth $5.8 billion USD, had 39 assembly lines spread across 35 countries, and possessed more than 400 patents enabling cross-licensing with the likes of IBM, Intel, and Texas Instruments while deriving licensing revenue from Japanese and Korean companies. Acer’s computers were assembled geographically close to where they were sold, and parts manufactured in Taiwan were shipped by sea and air to the assembly facilities. This distributed production model allowed Acer to become the leading PC company in Indonesia, Malaysia, South Africa, Mexico, Bolivia, Chile, Panama, Uruguay, Thailand, Philippines, and Taiwan. The assembly plants were also unique in that the local subsidiaries in any given geographic locale operated somewhat independently from Acer corporate with their own stakeholders and much of their own management. With this distributed model, production costs remained low despite the rising fortunes of Taiwan, inventory was reduced by 50%, and sales were increased by around 70% placing Acer in the top five PC vendors globally.

About those rising fortunes of Taiwan, Joel Kurtzman asked Stan Shih: “Some people say that Taiwan's younger generation is not as interested in working as hard as your generation. If it is true, do you worry about that?” To which Shih replied:

I don't worry about it. You know, I respect the younger generation for not wanting to work as hard. You see, we worked hard and our purpose in doing so was to improve conditions so that the next generation could have a better quality of life. That was our aim. So I am not complaining if the younger generation wants an easier life. They have higher education, and have better ways to create productivity. So why can't they enjoy a better life? I don't think we need to be concerned. That's the point of progress.

A major sign of Acer’s success was seen on the 23rd of January in 1997 when the company bought the mobile computing assets of Texas Instruments including the TravelMate and Extensa product lines and all of the assets associated with them.

In 1998, the company reorganized into five different groups: International Service, Sertek Service, Semiconductor, Information Products, Peripherals. This didn’t work. Acer Peripherals group became independent in 2001 as BenQ, and the contract manufacturing business as Wistron. Acer was now solely focused on computers and they had a new logo.

Stan Shih left Acer in 2004 to try and help further build up the Taiwanese industry. To this end, he founded iD SoftCapital Group along with some local VC veterans and other senior management from Acer. In addition to investment, the company offered consulting services to start ups. Gianfranco Lanci took over as president and CEO of Acer. Lanci had joined the company through the acquisition of TI’s mobile computing assets.

At this point, the computer market had changed significantly with notebook machines having become the primary growth segment. As Acer was able to keep lower inventories, manufacture with lower costs, and address local demands efficiently, they benefited greatly from this change. This boost to sales and earnings put them in an excellent position to buy Gateway, a purchase completed on the 17th of October in 2007 for $710 million. This purchase gave them the further opportunity to buy Packard Bell, and this purchase was completed on the 31st of January in 2008 for $46 million. As Gateway had recently purchased eMachines, Acer had essentially acquired three direct competitors.

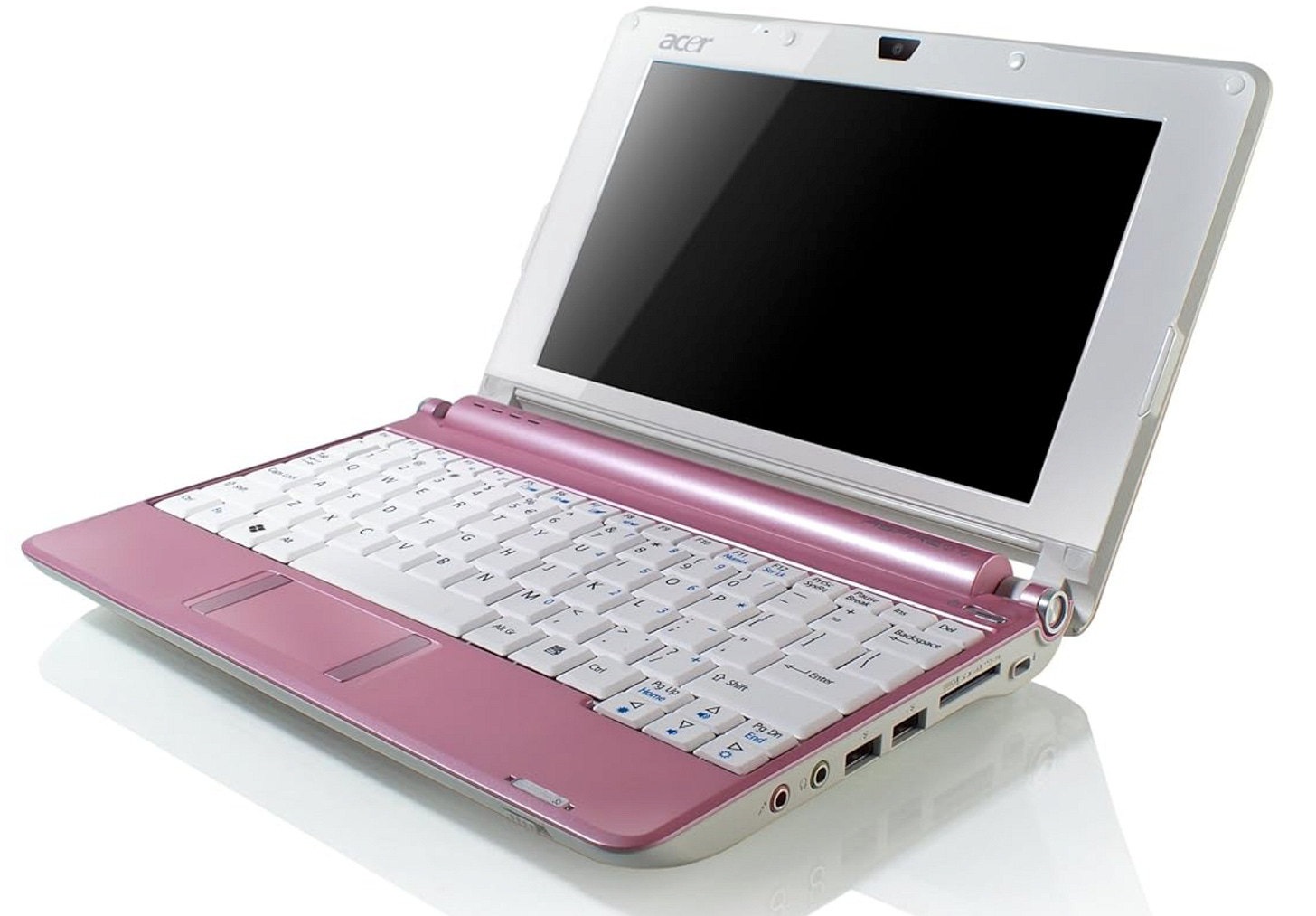

While Acer was busy buying up their failing competitors, Asus released the Eee PC. This was followed by similar machines like the Everex Cloud Book, the MSI Wind, and the HP Mini 1000. These all carry on from where Psion left things with miniature notebooks meant to provide modest computing power and some network connectivity. So, in 2008, Acer responded with the Aspire one. The first of these, the A110, featured a VIA C7 at 1GHz with a 400MHz FSB, a 7” display at 800 by 480, 512MB of DDR2, a VX800 S3 GPU, 2GB of flash used for Linpus Linux Lite, two USB 2.0 ports, a microphone-in jack, a speaker jack, a VGA port, a 56K modem, 10/100 ethernet, and a card reader (SD/MMC/MS). Fairly quickly, the A110 was followed by the A110L and A110X. These changed the CPU to the Intel Atom N270, increased the screen size to 8.9 inches with a resolution of 1024 by 600, expanded the RAM to 1GB and flash to 8GB for Linux systems (A110L) or 16GB for Windows XP (A110X). Further iterations were made that added HDD storage of 120GB to 160GB, webcams, 3G cellular data, WiMax, Bluetooth, IR, and varying sizes of battery. Pricing on a Windows model with N270, 8GB of flash storage, and 1GB of RAM was $379 in July of 2008. This line of little laptops became quite popular with Linux, UNIX, and OS X enthusiasts due to their low cost and extreme compatibility. Some Linux distributions made dedicated releases for the Aspire one including Joli OS, Ubuntu, Arch, Moblin, and Slitaz, but the majority of Linux distributions worked well on the machine. FreeBSD, OpenBSD, and NetBSD all had releases that worked on the Aspire one, and Mac OS X was made to work with OSX86 ports such as iAtkos, iDeneb, and Kalyway. With the exception of the ZG5 model, FreeDOS worked on the original line of Aspire ones as well.

With the notebook and netbook segments having fueled the company’s double digit growth year over year to becoming the second largest PC vendor globally, Lanci resigned on the 31st of March in 2011 after having disagreements with the board about the direction of the company. The company’s chairman, J.T. Wang, then took over as CEO. On the 25th of April, Jim Wong, previously senior vice president of Acer and president of the IT Products Group, became president. The company logo was refreshed in 2011 to become that which we see today.

From 2011 to 2013, the market began changing quite quickly. The Ultrabook market was heating up following the release of the MacBook Air, and consumers were expecting a bit more out of the notebook form factor. Acer had built itself on offering the best machines per dollar, and they didn’t adjust quickly enough. On the 5th of November in 2013, Acer announced that J.T. Wang would be succeeded by Jim Wong as CEO, but then on the 21st that same month, Acer announced that both resigned as a result of the company’s financial performance (loss of $446 million the prior quarter). None other than the company’s founder, Stan Shih, returned to fill the roles of chairman and president. Due to the financial strain, the man who’d made his employees shareholders was forced to layoff about 7% of Acer’s workforce. On the 23rd of December in 2013, Acer announced that Jason Chen, the former vice president of sales and marketing at TSMC, would join Acer as CEO on the 1st of January in 2014 with Shih remaining as chairman. Shih’s return was brief, and he retired for the second time in June of 2014, but was granted the title of honorary chairman. Today, George Huang serves as chairman, and Jason Chen continues as CEO and president. The company’s revenues for 2024 were over $9 billion USD, achieving growth of 4.7% over the previous year for the company as a whole, and representing six consecutive quarters of growth. The computing segment’s revenues grew by 66.8%.

My dear readers, many of you worked at, ran, or even founded the companies I cover here on ARF, and some of you were present at those companies for the time periods I cover. A few of you have been mentioned by name. All corrections to the record are sincerely welcome. Please feel free to leave a comment.